Abstract

Background

There is limited evidence on the clinical and economic benefit of achieving disease control in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS), thus we aimed to assess the impact of disease control on healthcare resource use (HCRU) and direct medical costs among US patients with PsA or AS over 1 year.

Methods

Data were derived from the US OM1 PsA/AS registries (PsA: 1/2013–12/2020; AS: 01/2013–4/2021) and the Optum Insight Clinformatics® Data Mart to identify adult patients with PsA or AS. Two cohorts were created: with disease control and without disease control. Disease control was defined as modified Disease Activity Index for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA28) ≤ 4 for PsA and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) < 4 for AS. Outcomes were all-cause inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department (ED) visits and associated costs over a 1-year follow-up period. Mean costs per person per year (PPPY) were assessed descriptively and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated for the likelihood of HCRU by logistic regression.

Results

The study included 1235 PsA (with disease control: N = 217; without: N = 1018) and 581 AS patients (with disease control: N = 342; without: N = 239). Patients without disease control were more likely to have an inpatient (aOR [95% CI]; PsA: 3.0 [0.9, 10.1]; AS: 7.7 [2.3, 25.1]) or ED (PsA: 1.6 [0.6, 4.2]; AS: 3.5 [1.5, 8.3]) visit than those with disease control. Those without disease control, vs. those with disease control, had greater PPPY costs associated with inpatient (PsA: $1550 vs. $443), outpatient (PsA: $1789 vs. $1327; AS: $2498 vs. $2023), and ED (PsA: $114 vs. $57; AS: $316 vs. $50) visits.

Conclusions

Findings from this study demonstrate lower disease activity among patients with PsA and AS is associated with less HCRU and lower costs over the following year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The clinical and economic benefit of achieving disease control in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) on healthcare resource use (HCRU) and medical costs has not been well characterized in a US population. |

This study sought to characterize HCRU among patients achieving disease control as compared to those who did not in a cross-sectional study, as well as to estimate the impact of disease control status on direct medical costs over the course of the next year. |

What was learned from this study? |

Patients with PsA and with AS with lower levels of disease activity had fewer inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient visits and lower direct medical costs than those who had higher levels of disease activity. |

These findings demonstrate that achieving disease control in PsA and AS may be associated with beneficial clinical and economic outcomes. |

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are progressive spondyloarthritis diseases characterized by inflammatory pain. Patients with PsA tend to experience peripheral inflammatory arthritis in the hands and feet, as well as psoriatic skin lesions. Patients with AS have more axial inflammatory arthritis, typically localized to the spine [1,2,3]. For most chronic inflammatory diseases, achieving a target of stable or low disease activity or remission is the primary treatment target [4, 5]. Unfortunately, less than a third of patients with PsA and AS achieve remission after six months of treatment [6]. Most patients who do achieve remission relapse within a year. Moreover, in patients who relapse and restart therapy, nearly half do not again achieve remission and some do not respond to therapy at all [6,7,8,9]. Patients with poor disease control report significantly reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [10, 11]. Aside from improvement in HRQoL, achieving disease control may also result in reduced healthcare resource use (HCRU), such as a reduced number of healthcare visits or medication use. In turn, patients may also have reduced disease-related direct medical costs, which has also been shown to improve patient-reported HRQoL [12]. As such, HRQoL improvements are not only beneficial to the patient, but also the healthcare system and public or private payers. Indeed, patients with AS in Central and Eastern Europe who achieved low disease activity status after 12 months had up to an 83% reduction in the number and length of hospitalizations, as well as a reduced number of healthcare provider visits [13]. Therefore, it is critical to understand the clinical and economic benefit of disease control in patients with PsA and AS, which has not been characterized in a US population. The objective of this study was to assess the impact of achieving disease control on HCRU and associated costs over 1 year among US patients with PsA or AS.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The data source for this study was the OM1 PsA and AS Registry, a subset of the OM1 Real-World Data Cloud (OM1, Inc, Boston, MA, USA), a large, linked clinical and administrative dataset derived from medical and pharmacy claims and electronic medical record data. This study utilized data collected on patients (age ≥ 18 years) between 2013 and 2021 (PsA: 1/2013–12/2020; AS: 01/2013–4/2021) with an International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision (ICD-9) or 10th Revision (ICD-10), codes for PsA (696.0 and L40.5x, respectively) or AS (720.0 and M45.x, respectively). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the current Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice, Good Epidemiology Practices, and applicable regulatory requirements. This study utilized de-identified data from an administrative claims database, thus no ethics committee approval was required.

Patients with PsA or AS meeting the following criteria were included in the study: (1) continuous enrollment in the registry for both baseline and follow-up periods (i.e., pre- and post-index periods) and (2) complete data for all components of the disease activity measures. In patients with PsA, disease activity was measured using the modified Disease Activity Index for PsA with 28 joint counts (DAPSA28; range, 1–154) with a score of ≤ 4 indicating remission [14]. The DAPSA28 includes 28 tender joint count (TJC), 28 swollen joint count (SJC), Patient’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA) by visual analog scale (VAS, range = 0–10), pain by VAS (range = 0–10), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. The following algorithm was used to estimate DAPSA28 [14]:

Eligible patients had ≥ 1 recorded score and/or level for each item. For patients with AS, disease control was defined as a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score < 4; a score ≥ 4 is a recognized indication of active disease in clinical practice [15]. The BASDAI questionnaire incorporates patient-reported severity of back pain, fatigue, peripheral joint pain, swelling, localized tenderness, and duration and severity of morning stiffness; scores are assessed by a numerical rating scale (0–10) or by VAS (1–10 cm) [15]. For both cohorts, the index date was a random date selected on or after patients recorded ≥ 2 DAPSA28 or BASDAI scores indicating disease control; patients without disease control (e.g., DAPSA28 > 4 or BASDAI ≥ 4) were randomly assigned an index date on or after the date that a DAPSA28 or BASDAI measurement indicated poor disease control.

Outcomes

All-cause HCRU, including inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department (ED) visits over 1-year post-index, was analyzed. The likelihood of having inpatient or ED visits during the follow-up period between patients not achieving disease control relative to those who did achieve disease control was also assessed. Mean annual cost data for inpatient, outpatient, and ED visits were obtained from adjudicated administrative claims data using the Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart Database (2007–2019); this dataset is derived from a database of administrative health claims for members of large commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans and was used to estimate costs since the OM1 registry only contains charge data (i.e., unadjudicated claims). Mean cost per single event for each HCRU type (i.e., inpatient, outpatient, or ED visit) was derived from the Optum database and used in the regression model to calculate per patient per year (PPPY) costs. For PsA, the mean costs per inpatient, outpatient, and ED visit were $22,140, $176, and $1140, respectively; for AS, mean costs were $22,430, $416, and $1262. PPPY HCRU costs were derived by multiplying the average cost per patient per inpatient/ED visit (from Optum) by the respective number of inpatient/ED visits in the 1-year follow-up period (from OM1). Medication costs were not incorporated into the HRCU costs. All data were stratified by achievement of disease control (i.e., yes or no).

Statistical Analysis of Data

All-cause HCRU are reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD) of number of inpatient, outpatient, or ED visits per 100 patients. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for likelihood of inpatient or ED visit using a logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, region, race, smoking status, body mass index, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), insurance type, baseline medication use (i.e., biologic/conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [b/csDMARD] for PsA and b/csDMARD, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAID], and opioids for AS), baseline HCRU, index year, and months from first diagnosis to index date. aORs were not calculated for outpatient visits for people with PsA or AS because nearly all patients had at least one outpatient visit in the follow-up period, therefore logistic regression analyses were infeasible.

Results

Patient Demographics

In total, there were 1235 patients with PsA and 581 patients with AS who met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study (Fig. 1). Among patients in the PsA cohort, patients without disease control were significantly older (mean ± SD; 58.6 ± 12.9 vs. 56.4 ± 13.4, p = 0.03), more often female (65.9 vs. 44.7%, p < 0.01), had higher mean CCI scores (0.18 ± 0.64 vs. 0.07 ± 0.32, p = 0.01), and were less likely to use bDMARDs at baseline (41.9 vs. 50.7%, p = 0.02) compared to patients with disease control (Table 1). Among patients in the AS cohort, patients without disease control were significantly younger than those with disease control (48.8 ± 14.7 vs. 51.2 ± 15.8, p = 0.03). Significantly more patients without disease control were female (57.7 vs. 29.2%, p < 0.01) and reported significantly more (p ≤ 0.05) baseline csDMARD, NSAID, and opioid use.

HCRU at Baseline and 1-Year Follow-Up

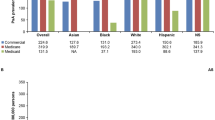

Among patients with PsA, the mean number of inpatient and ED visits per 100 patients at baseline was similar between groups (mean ± SD; inpatient: 1 ± 14 vs. 1 ± 17; ED: 2 ± 21 vs. 2 ± 18; Fig. 2a); patients without disease control had significantly more outpatient visits per 100 patients than those with disease control (217 ± 267 vs. 153 ± 175, p < 0.01). At the 1-year follow-up, patients without disease control had significantly more inpatient visits (7 ± 34 vs. 2 ± 13, p < 0.01) and outpatient visits (1015 ± 944 vs. 753 ± 509, p < 0.01) and numerically higher ED visits per 100 patients (10 ± 71 vs. 5 ± 35, p = 0.14). While PsA patients without disease control were more likely to have inpatient (aOR [95%CI]: 3.0 [0.9, 10.1]) or ED visits (1.6 [0.6, 4.2]) in adjusted analyses, these results were not statistically significant (Fig. 3). At baseline, patients with AS without disease control reported similar inpatient visits per 100 patients (5 ± 28 vs. 6 ± 29; Fig. 2b), statistically higher outpatient visits (802 ± 817 vs. 600 ± 679, p < 0.01), and numerically higher ED visits per 100 patients (32 ± 218 vs. 11 ± 43) compared with patients with disease control. At the 1-year follow-up, AS patients not achieving disease control had significantly higher inpatient visits (12 ± 52 vs. 4 ± 27, p = 0.03) and ED visits (25 ± 114 vs. 4 ± 27, p = 0.01) and numerically higher outpatient visits (600 ± 840 vs. 486 ± 570, p = 0.07) per 100 patients than patients with disease control. In adjusted analyses, patients not achieving disease control were significantly more likely to have inpatient (7.7 [2.3, 25.1]; p < 0.001) or ED visits (3.5 [1.5, 8.3]; p < 0.01; Fig. 3).

Likelihood of inpatient or ED visits in patients without disease control relative to patients with disease control. *aORs for patients not achieving disease control relative to those achieving disease control. aOR adjusted odds ratio, AS ankylosing spondylitis, CI confidence interval, PsA psoriatic arthritis

Mean PPPY at Baseline and 1-Year Follow-up

At baseline, patients with PsA had the same mean [range] estimated inpatient and ED medical costs PPPY (inpatient costs: $221 [$0–$3053]; ED costs: $23 [$0–$853]; Fig. 4a) regardless of disease control status; patients without disease control had numerically higher outpatient costs ($382 [$0–$52,029] vs. $270 [$0–$36,684]) than patients with disease control. However, after 1 year, estimated mean medical costs PPPY for patients without disease control were higher than those reported for patients with disease control (inpatient costs: $1550 [$0–$21,370] vs. $443 [$0–$6106]; ED costs: $114 [$0–$4264] vs. $57 [$0–$2132]; outpatient costs: $1789 [$0–$243,360] vs. $1327 [$0–$180,542]). At baseline, patients with AS without disease control had numerically lower inpatient costs ($1121 vs. $1346) and higher estimated outpatient ($3339 vs. $2498) and ED costs ($404 vs. $139) PPPY as compared to patients with disease control (Fig. 4b). At the 1-year follow-up, mean inpatient ($2692 [$0–$32,381] vs. $897 [$0–$10,794]), outpatient ($2498 [$0–$146,579] vs. $2023 [$0–$118,729]) and ED costs ($316 [$0–$4929] vs. $50 [$0–$789]) were higher for AS patients without disease control versus those with disease control.

Estimated mean costs per person per year at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Cost per single event (i.e., inpatient, outpatient, and ED visit) derived from the Optum database was used to inform the regression model. For PsA, mean costs were $22,140, $176, and $1140, respectively, and for AS mean costs were $22,430, $416, and $1262, per inpatient, outpatient, and ED visit, respectively. AS ankylosing spondylitis, ED emergency department, PPPY per patient per year, PsA psoriatic arthritis, USD United States dollar. *p < 0.01 between patients achieving disease control versus those not achieving disease control

Discussion

These data demonstrate that patients with PsA and AS with lower disease activity also had lower HCRU. Compared with patients without disease control, those with disease control had fewer inpatient and ED visits and lower associated medical costs in the following year. While this study reports findings for PsA and AS, similar findings have been reported in other studies on overall PsA- or AS-related costs [16, 17]. A key takeaway from this study is that, during the year after achieving disease control, patients had consistently lower medical costs compared to those who did not achieve disease control. Indeed, a study in patients with AS in Europe demonstrated that patients who responded to treatment had fewer inpatient visits and took fewer sick leave days as compared to those who did not respond to treatment, further substantiating the benefit of achieving disease control [13]. Interestingly, this study also showed that a majority of the patients not achieving disease control were female, which has been demonstrated in other studies of patients with PsA [18,19,20,21].

Multiple studies in other rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, have demonstrated that achieving remission has a significant impact on HCRU and medical costs for the patient, as well as a reduced burden on the healthcare system [22,23,24,25]. Likewise, remission is often accompanied by improved physical functioning, and therefore work abilities; thus, disease control also has a societal impact [25]. However, studies have shown that, despite achieving stringent disease control measures, many patients still report residual disease symptoms [26,27,28]. It is important that providers take a more patient-centered approach, not relying solely on measures of disease activity, but also incorporating patient-reported outcomes, such as pain, fatigue, and functional impairment, as these are outcomes that are important to patients. As such, personalized treatment plans and shared decision making is not only beneficial to the patient and their physician, but also to the health system and payers [29]. Indeed, findings from the FORWARD observational databank showed that increasing functional disability, as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), was significantly associated with greater HCRU and medical costs [30].

A strength of this retrospective, cross-sectional observational study is that it utilized a large dataset with detailed information on demographics, clinical and patient-reported outcomes, treatment history, and history of comorbidities. With the OM1 PsA and AS databases, which has more detail available than traditional claims databases, disease control could be defined with clinical data, albeit not with typical psoriatic disease measures. Limitations are that, due to the cross-sectional study design, data were not controlled for all potential confounders and temporal and/or causal links cannot be inferred. Thus, these data are only generalizable to those patients who have insurance within the dataset and do not represent the entirety of the United States population with PsA or AS. Likewise, patient selection criteria (i.e., requirement for complete data including CRP) and the dichotomization by “ever achieved control” vs. “never achieved control” during this study may introduce bias into the study findings as it may increase the likelihood of poorer outcomes in those without disease control. As such, this study randomly selected the date among patients with ≥ 2 recorded disease activity measures who eventually achieved low disease activity as defined in this study. For patients with AS, BASDAI (a patient-reported outcome) was used to assess disease control, whereas a modified DAPSA28 (a composite outcome) was used in patients with PsA. Assessments such as minimal disease activity (PsA) or Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (AS) would be the most ideal measures, however the data source was limited in its disease control metrics, thus DAPSA28 and BASDAI were leveraged. Both measures are routinely used to assess disease activity, but it is important to state that they are not equivalent. Moreover, this study utilized the modified DAPSA28, which incorporates 28 tender joint counts and 28 swollen joint counts, instead of the full DAPSA, which incorporates 68 tender joint counts and 66 swollen joint counts. As such, the rates of remission may be overestimated in this population. However, studies have shown good correlation between the two measures and highlight that DAPSA28 is a sufficient measure when full DAPSA assessments are not available [14]. OM1 is an open-claims database, thus complete capture of HCRU cannot be guaranteed and the observed HCRU may be underestimated in this study. Likewise, indirect methods of linking costs from a different database to the OM1 resource use may differ from the actual costs incurred.

Conclusions

The findings from this study suggest that achievement of disease control in patients with PsA or AS was associated with fewer inpatient and outpatient visits and lower direct medical costs than those who did not achieve disease control. Highlighting these clinical and economic benefits of achieving disease control in PsA and AS may be of significant benefit in improving patient outcomes, including non-pharmacy healthcare costs and hospitalizations.

References

Raychaudhuri SP, Wilken R, Sukhov AC, Raychaudhuri SK, Maverakis E. Management of psoriatic arthritis: early diagnosis, monitoring of disease severity and cutting edge therapies. J Autoimmun. 2017;76:21–37.

Mease PJ. Measures of psoriatic arthritis: tender and swollen joint assessment, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), Modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI), Mander/Newcastle Enthesitis Index (MEI), Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC), Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis Score (MASES), Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI), Patient Global for Psoriatic Arthritis, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life (PsAQOL), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC), Psoriatic Arthritis Joint Activity Index (PsAJAI), Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA), and Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (CPDAI). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(Suppl 11):S64-85.

Taurog JD, Chhabra A, Colbert RA. Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2563–74.

Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(10):1285–99.

Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):700–12.

Perrotta FM, Delle Sedie A, Scriffignano S, et al. Remission, low disease activity and improvement of pain and function in psoriatic arthritis patients treated with IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors. A multicenter prospective study. Reumatismo. 2020;72(1):52–9.

Pina Vegas L, Penso L, Claudepierre P, Sbidian E. Long-term persistence of first-line biologics for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the French Health Insurance Database. JAMA Dermatol. 2022.

Moreno M, Gratacos J, Torrente-Segarra V, et al. Withdrawal of infliximab therapy in ankylosing spondylitis in persistent clinical remission, results from the REMINEA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):88.

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ogdie A, et al. Treatment-to-target with apremilast in psoriatic arthritis: the probability of achieving targets and comprehensive control of disease manifestations. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(6):814–21.

Bodur H, Ataman S, Rezvani A, et al. Quality of life and related variables in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(4):543–9.

Coates LC, Orbai AM, Morita A, et al. Achieving minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis predicts meaningful improvements in patients’ health-related quality of life and productivity. BMC Rheumatol. 2018;2:24.

Olivieri I, Cortesi PA, de Portu S, et al. Long-term costs and outcomes in psoriatic arthritis patients not responding to conventional therapy treated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: the extension of the Psoriatic Arthritis Cost Evaluation (PACE) study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(1):68–75.

Opris-Belinski D, Erdes SF, Grazio S, et al. Impact of adalimumab on clinical outcomes, healthcare resource utilization, and sick leave in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: an observational study from five Central and Eastern European countries. Drugs Context. 2018;7: 212556.

Michelsen B, Sexton J, Smolen JS, et al. Can disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis be adequately assessed by a modified Disease Activity index for PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) based on 28 joints? Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(12):1736–41.

Zochling J. Measures of symptoms and disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Scale (ASQoL), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Global Score (BAS-G), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), Dougados Functional Index (DFI), and Health Assessment Questionnaire for the Spondylarthropathies (HAQ-S). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(Suppl 11):S47-58.

Palla I, Trieste L, Tani C, et al. A systematic literature review of the economic impact of ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(4 Suppl 73):S136–41.

McHugh N, Maguire A, Handel I, et al. Evaluation of the economic burden of psoriatic arthritis and the relationship between functional status and healthcare costs. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(5):701–7.

Eder L, Tony HP, Odhav S, et al. Responses to ixekizumab in male and female patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from two randomized, phase 3 clinical trials. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9(3):919–33.

Tarannum S, Leung YY, Johnson SR, et al. Sex- and gender-related differences in psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022.

Orbai AM, Perin J, Gorlier C, et al. Determinants of patient-reported psoriatic arthritis impact of disease: an analysis of the association with sex in 458 patients from fourteen countries. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(12):1772–9.

Theander E, Husmark T, Alenius GM, et al. Early psoriatic arthritis: short symptom duration, male gender and preserved physical functioning at presentation predict favourable outcome at 5-year follow-up. Results from the Swedish Early Psoriatic Arthritis Register (SwePsA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(2):407–13.

Bergman M, Zhou L, Patel P, et al. Healthcare costs of not achieving remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the United States: a retrospective cohort study. Adv Ther. 2021;38(5):2558–70.

Curtis JR, Chen L, Greenberg JD, et al. The clinical status and economic savings associated with remission among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: leveraging linked registry and claims data for synergistic insights. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(3):310–9.

Ten Klooster PM, Oude Voshaar MAH, Fakhouri W, et al. Long-term clinical, functional, and cost outcomes for early rheumatoid arthritis patients who did or did not achieve early remission in a real-world treat-to-target strategy. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(10):2727–36.

Barnabe C, Thanh NX, Ohinmaa A, et al. Healthcare service utilisation costs are reduced when rheumatoid arthritis patients achieve sustained remission. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1664–8.

Coates LC, de Wit M, Buchanan-Hughes A, et al. Residual disease associated with suboptimal treatment response in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review of real-world evidence. Rheumatol Ther. 2022;9(3):803–21.

Karadag O, Dalkilic E, Ayan G, et al. Real-world data on change in work productivity, activity impairment, and quality of life in patients with psoriatic arthritis under anti-TNF therapy: a postmarketing, noninterventional, observational study. Clin Rheumatol. 2021.

Lai TL, Au CK, Chung HY, et al. Fatigue in psoriatic arthritis: Is it related to disease activity? Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24(3):418–25.

Danve A, Deodhar A. Treat to target in axial spondyloarthritis: what are the issues? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(5):22.

Ogdie A, Hwang M, Veeranki P, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with functional status in patients with psoriatic arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(Suppl 10).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Boya Lin and Danny Quach, formerly of AbbVie, for their contributions to study conception and design.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work/study, and Rapid Service Fee, was funded by AbbVie Inc. AbbVie participated in the study design, research, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing, reviewing, and approving the publication. All authors had access to the data results, and participated in the development, review, and approval of this abstract. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Medical Writing Support

Medical writing services provided by Samantha D. Francis Stuart, PhD, of Fishawack Facilitate Ltd, part of Fishawack Health, and funded by AbbVie.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

J Patel, P Zueger, and CD Saffore substantially contributed to study conception and design; I Topuria, C Cavanaugh, J Patel, P Zueger, and CD Saffore contributed to data acquisition; S Fang contributed to data analysis. All authors contributed to interpretation of results and in drafting/revising critically for intellectual content.

Prior Presentation

The authors confirm that these data have not been previously presented or publicly shared.

Disclosures

MJ Bergman has received speaking/consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi, and Scifer; and is a shareholder of Merck and Johnson & Johnson. P Zueger, J Patel, CD Saffore, S Fang, and J Clewell are employees of AbbVie and may own stock. I Topuria and C Cavanaugh are employees of OM1, Inc. and may own stock. A Ogdie has received consulting fees from Amgen, AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, CorEvitas (previously Corrona, LLC), Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB, and has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Rheumatology Research Foundation, National Psoriasis Foundation, AbbVie, Amgen, Pfizer, and Novartis.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the current Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice, Good Epidemiology Practices, and applicable regulatory requirements. This study utilized de-identified data from an administrative claims database, thus no ethics committee approval was required.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergman, M.J., Zueger, P., Patel, J. et al. Clinical and Economic Benefit of Achieving Disease Control in Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Retrospective Analysis from the OM1 Registry. Rheumatol Ther 10, 187–199 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00504-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00504-2