Abstract

Introduction

The inclusion of certain variables in remission formulas for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) may give rise to discrepancies. An increase in patient global assessment (PGA), a variable showing the patient's self-evaluation of their disease activity, may alone tilt a patient out of remission when using certain remission-assessing methods. This study aimed to explore differences in remission rates among various formulas and the impact of PGA and other clinical variables on the calculation of remission.

Methods

Data were collected from RA patients monitored during the years 2015–2019 at an outpatient clinic in southern Norway. Linear and logistic regression assessed associations between PGA, other RA-related variables, and remission-assessing methods.

Results

Remission rates were 23%, 65%, and 73% in 2019 when assessing the same 502 RA patients using Boolean remission, Boolean remission without PGA, and the disease activity score (DAS) with C-reactive peptide [DAS28(3)-CRP] method, respectively. Among the same population that year, 27% reported PGA ≤ 10, 74% had a tender joint count of ≤ 1, 85% had a swollen joint count of ≤ 1, and 86% had CRP ≤ 10. Pain (standardized coefficient β = 0.7, p < 0.001) was most strongly associated with PGA. Pain, fatigue, and morning stiffness were substantially associated with the remission-assessing methods that incorporated PGA.

Conclusions

Since PGA is strongly associated with the patient’s perception of pain and may not reflect the inflammatory process, our study challenges the application of remission-assessing methods containing PGA when monitoring RA patients in the outpatient clinic. We recommend using measures that are less likely to be associated with noninflammatory pain and psychosocial factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study |

Several composite measures are recognized to define remission status in rheumatoid arthritis, but they do not provide comparable scores |

Most measures incorporate patient self-evaluation, which, while elevated, can be solely responsible for not reaching remission even though the remaining variables reflect an absence of inflammation |

This study seeks to assess the comparability of remission rates calculated using different remission-assessing methods in a rheumatoid arthritis outpatient clinic cohort |

What was learned from the study |

Remission rates calculated for the same group of rheumatoid arthritis patients differ when using various remission-assessing measures, particularly as patient self-evaluation is integrated into their calculation |

Patient self-evaluation is important when assessing disease burden; however, this study challenges the applicability of the patient self-evaluation variable when utilizing potent and costly anti-inflammatory drugs for a noninflammatory status |

Introduction

In 1981, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) defined rheumatoid arthritis (RA) remission as the absence of any inflammatory RA disease activity [1]. According to the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for managing RA, treatment should aim for remission or low disease activity [2]. An analysis by Mian et al. of 22 RA treatment guidelines (2000–2017) found the disease activity score-28 (DAS28) to be the most frequently recommended parameter to guide RA treatment and assess remission [3], despite the possibility of having multiple swollen joints while in DAS28 remission [4].

A less frequently recommended [3] and more stringent alternative for assessing remission (defined by the ACR/EULAR committee) is Boolean remission, which has the criteria of a score of ≤ 1 for the tender 28-joint count (TJC28), the swollen 28-joint count (SJC28), C-reactive peptide (CRP) (mg/dl), and the patient global assessment (PGA) [visual analog scale (VAS) 0–10] [4]. However, a recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials by Ferreira et al. has questioned the importance of using PGA in Boolean remission, as it places greater emphasis on the patient's perception of disease burden, which may be influenced by noninflammatory mechanisms [5]. The incorporation of PGA scoring into other remission-assessing methods should also be questioned, as it may potentially lead to misestimation of inflammatory remission rates and consequently to overtreatment.

The primary aim of this study was to compare remission rates using different remission-assessing methods in a RA outpatient clinic cohort, in particular, to reveal the impact of PGA. The second aim was to examine associations of RA-related variables with PGA, and the third was to explore associations of different RA-related variables with remission status in various measures.

Methods

Patient Inclusion and Data Collection

Data for this cross-sectional study were obtained (2015–2019) from a rheumatological outpatient clinic in southern Norway. Patient monitoring at the outpatient clinic was standardized using the computer tool GoTreatIT® Rheuma (www.diagraphit.com). Data were extracted from the clinic database using predefined queries. One query extracted RA patients data who had at least one registered visit in the analysed year. The most recent visit was extracted if there were multiple visits during the same year. The anonymized data files were analysed using EXCEL and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Descriptive variables included age, sex, body mass index (kg/m2), current smoking status, years of education, disease duration, rheumatoid factor (RF), and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (aCCP). Variables reflecting disease activity encompassed erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (mm/h), CRP (mg/L), SJC28 (0–28 joints), TJC28 (0–28 joints), and investigator global assessment (IGA) (VAS 0–100 mm). The patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) included PGA, pain (VAS 0–100 mm), fatigue (VAS 0–100 mm), morning stiffness (reported in 15-min units), and the modified health assessment questionnaire (MHAQ) [6].

Composite Disease Activity Score and Remission Definitions

The composite disease activity scores (CDASs) included in this study cover the addition-based methods, the simple disease activity index (SDAI) (TJC28, SJC28, CRP, PGA, IGA) [7] and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI) (TJC28, SJC28, PGA, IGA) [8], and the algorithm-based DAS28(3) (TJC28, SJC28, CRP) [9] and DAS28(4) (TJC28, SJC28, CRP, PGA) [9]. Among the assessed CDASs, remission cutoff values were ≤ 2.6 for both DAS28(3) and DAS28(4) [9], ≤ 2.8 for CDAI [8], and ≤ 3.2 for SDAI [7]. Patients were stratified for analysis as having either remission or non-remission.

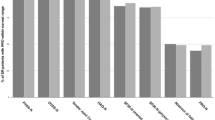

ACR/EULAR Boolean remission (4-variable remission) is defined as scores of ≤ 1 for TJC28, SJC28, CRP, and PGA [4]. However, since the extracted CRP is measured in mg/L and the PGA by a VAS of 0–100 mm, the Boolean remission CRP and PGA were redefined as ≤ 10. Modified 4-variable remission rates were examined using different PGA cutoffs of ≤ 20, ≤ 30, ≤ 40, ≤ 50, ≤ 60, ≤ 70, ≤ 80, and ≤ 90 (Fig. 1). PGA ≤ 100 was not included, as only 11 patients (2%) scored a PGA of 91–100. A 3-variable remission was defined as Boolean remission without PGA (i.e. TJC28 ≤ 1, SJC28 ≤ 1, and CRP ≤ 10). Subjective 2-variable remission (TJC28 ≤ 1 and PGA ≤ 10) and objective 2-variable remission (SJC28 ≤ 1 and CRP ≤ 10) were also reported (Table 2). RA patients in the study were also assessed with single-component cutoffs: TJC28 ≤ 1, SJC28 ≤ 1, CRP ≤ 10, PGA ≤ 10, PGA ≤ 20, and IGA ≤ 10. Since the difference in the remission rates between the assessed years was only minimally statistically significant, the comparison in Fig. 1 is for 2019 only.

Comparing composite measures of disease activity and variants of Boolean remission in 2019. Note: data are presented as percentages of n = 502 in 2019. The figure compares various cutoffs of the patient global assessment in Boolean remission with the remission of composite measures of disease activity and 3-variable remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients in an ordinary outpatient clinic in southern Norway. 4-variable remission is achieved when C-reactive peptide (CRP) ≤ 10, tender 28-joint count (TJC28) ≤ 1, swollen 28-joint count (SJC28) ≤ 1, and PGA ≤ 10. 3-variable remission is achieved when CRP ≤ 10, TJC28 ≤ 1, and SJC28 ≤ 1. 4VR 4-variable remission, PGA patient global assessment, CDAI clinical disease activity index, SDAI simple disease activity Index, 3VR 3-variable remission, DAS28 disease activity score with CRP

Treatment

The annual data collection (2015–2019) from the RA patients included information on biological and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (b/tsDMARDs), which comprised tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) (etanercept reference, etanercept SB4, infliximab reference, infliximab CT-P13, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol), non-TNFi (rituximab reference, rituximab GP2013, abatacept, and tocilizumab), and tsDMARDs (baricitinib and tofacitinib). The collected data also contained information on prednisolone and conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) such as methotrexate (MTX). Monotherapy for b/tsDMARDs and TNFi, as well as no treatment, i.e. neither b/tsDMARD, csDMARDs, nor prednisolone, was also reported.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are reported as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables as means with standard deviations (SDs) or means with ranges. Changes in and associations between variables over 5 years were analysed with SPSS using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Only patients with a complete dataset for TJC28, SJC28, CRP, PGA, and IGA were analysed. To examine bias due to missing data, the included patients were compared with those without a complete dataset. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Univariable and multivariable linear regression with stepwise variable selection was used to assess the association between demographic and disease characteristic variables and PGA. Logistic regression was used to assess the association between demographic and disease characteristic variables and various remission-assessing methods. The variables responsible for the different calculations or assessments of the various remissions were omitted in the logistic regression analysis. For linear regression, the standardized coefficient β and unstandardized coefficient B were reported along with the 95% confidence intervals. For logistic regression, the odds ratios (OR) were reported along with the 95% confidence intervals. Due to the minimal differences in the assessed demographics, disease activity measures, and patient-reported outcomes among the 5 years of the study period, we decided to report only the 2019 regression analysis for clarity purposes. Supplementary Table 2 shows a variant of the multivariate regression analysis, albeit subgrouped based on the 3-variable remission and moderate–high disease activity in RA patients with DAS28(4), CDAI, and SDAI.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (REC) of Middle Norway (2010/3078) and followed the ethical principles of medical research involving human subjects of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (and its later amendments). No consent from the patients was required by the REC of Middle Norway, as all data were anonymized and collected as part of routine clinical care.

Results

Demographics, Disease Activity, and Patient-Reported Outcomes

Table 1 presents the demographic variables, RF, aCCP, disease activity variables, PROMs, and treatment for the years 2015–2019. The number of RA patients in the included dataset ranged from 613 to 502 (2015–2019). Over the 5 years, no significant change in the mean values of the demographic variables, PROMs, aCCP positive rate (73.8%), RF positive rate (68.8%), TJC28 (1.3), SJC28 (0.9), and CRP (6.1 mg/L) was observed. The mean changes in ESR (14.6, range 12.6–18.0 mm/h) and IGA (9.6, 7.8–10.6) across the 5 years were significant; however, no significant change was noted for DAS28(3) (2.3), DAS28(4) (2.4), CDAI (6.4), or SDAI (7.0).

Approximately 40% of the patients did not have a complete dataset and were excluded from the analysis. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, there were only minor differences between the excluded and included patients.

Comparison of Remission Rates and the Impact of PGA

Table 2 presents the remission rates based on DAS28(3), DAS28(4), CDAI, SDAI, ACR/EULAR Boolean remission, various subgroups of Boolean remission, and individual measures. Over the 5 years, none of the mean remission rates were significantly different except for IGA ≤ 10. The average remission rates ordered from lowest to highest are shown in Fig. 1. A gradual increase in the PGA cutoff in Boolean 4-variable remission was linked to an observable increase in the remission rate. When comparing these different remission rates using an increasing PGA cutoff in 4-variable remission (Fig. 1), the remission rates based on SDAI and CDAI were similar to Boolean 4-variable remission with PGA cutoffs of ≤ 20 and ≤ 30. In comparison, the 3-variable, DAS28(3), and DAS28(4) remission rates were located beyond a cutoff of ≤ 90 PGA.

Treatment

The mean 5-year percentage of RA patients who received any type of b/tsDMARD was 41.3%, and it was 10.1% for those who received b/tsDMARDs as monotherapy. Among the same analysed study population, the 5-year average percentage of patients who received TNFi (no csDMARDs or prednisolone) was 21.5%, and it was 5.0% for those who only received TNFi. Also, an average of 65.7% of the patients were registered as receiving csDMARDs, 56.2% were registered as receiving MTX, and 47.5% were registered as receiving prednisolone. An average of 7.3% did not receive either b/tsDMARDs, csDMARDs, or prednisolone. Both TNFi and b/tsDMARD monotherapy showed statistically significant changes over the 5 years. Supplementary Table 3 includes a treatment comparison between the examined and excluded patients.

Associations of Relevant Variables with Patient Global Assessment

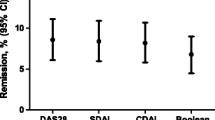

Table 3 shows the associations of different variables (univariate and multivariate models) with PGA in 2019 according to a linear regression. For a univariable linear regression, only PROM variables achieved β ≥ 0.5 with a p-value < 0.001; these variables included pain (β = 0.9), MHAQ (β = 0.7), fatigue (β = 0.7), and morning stiffness (β = 0.5). In a multivariable regression model with all covariates included, only pain (β = 0.7), fatigue (β = 0.2), and MHAQ (β = 0.1) were significantly associated with PGA, with pain having the strongest association. Similar outcomes were observed for the multivariable regression model after stepwise variable selection. Interestingly, similar findings were observed for the association between pain and PGA in other disease activity subgroups, including moderate–high disease activity and 3-variable remission (Supplementary Table 2).

Association of Variables with Remission Status

Supplementary Table 1 reports the associations as ORs between different variables and remission assessed through logistic regression. TJC28 had a significant association with objective 2-variable remission, and IGA had significant associations with all except subjective 2-variable remission. Among the PROMs, pain had significant associations with DAS28(4), CDAI, SDAI, 4-variable remission, 4-variable-remission with a PGA cutoff of ≤ 20 (4-variable remissionPGA20), and subjective 2-variable remission. Fatigue had significant associations with CDAI remission, SDAI remission, 4-variable remission, 4-variable remissionPGA20, and subjective 2-variable remission. Morning stiffness had significant associations with CDAI remission, SDAI remission, and 4-variable remissionPGA20. PGA had no significant associations with scores that did not incorporate the variable [3-variable remission, DAS28(3) remission, objective 2-variable remission].

Discussion

The main finding of our study is the large variation in RA remission rate between the remission-assessing methods: rates ranged from 23% for Boolean remission to 73% for DAS28(3) remission (in 2019). For Boolean remission in particular, we should highlight the impact of PGA, which is strongly associated with pain, on the remission rates.

In Fig. 1, among the remission-assessing methods incorporating PGA, 4-variable remission (23%), CDAI (37%), and SDAI (38%) had substantially lower remission rates than DAS28(4) (67%). A discrepancy in remission rate when using different remission-assessing methods has been reported previously across Europe [10]. The DAS28(4) calculation differs as it uses an algorithm that gives PGA much weaker power, giving it a reduced impact compared to the other variables. In contrast, 4-variable (Boolean) remission, CDAI, and SDAI all give equal power to their variables. The remission-assessing methods without PGA produced remission rates of 65% and 73% for 3-variable remission and DAS28(3), respectively. Similar discrepancies between methods have been demonstrated elsewhere [11, 12]. We confirmed that attaining remission is dependent on the method of assessment [12,13,14,15,16].

While DAS28 deprioritizes PGA, the same algorithm allows remission to be attained with multiple swollen joints, which can consequently lead to radiographic joint damage despite the patient being “in remission” [17]. As a reciprocal, a patient must have TJC28, SJC28, CRP, and PGA ≤ 1.0 to attain a 4-variable remission [4]. However, this approach may overemphasize subjectivity, as patients without active joints and normal CRP levels can still report elevated PGA scores, which shift disease activity above the remission threshold due to noninflammatory causes, e.g. fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, depression, psychological pain and distress, and other comorbidities [18,19,20,21]. A study by Inanc et al. observed an increase in anxiety, fatigue, and depression among RA patients who did not attain 4-variable remission but achieved a DAS28-ESR remission [22]. Among these measures, PGA and depression were the most important contributors to nonconcordance between DAS28-ESR and Boolean remission rates. In order to avoid false nonremission and possibly improper targeted treatment, Inanc et al. proposed the implementation of separate supplementary assessments for anxiety, fatigue, fibromyalgia, and depression among RA patients who do not attain 4-variable remission [22].

Solutions to lessen the restrictiveness of 4-variable remission include threshold modification [23] and 3-component variant remission definition [24]. The latter is exemplified by excluding PGA from Boolean remission when assessing disease activity, albeit restricting it to disease impact [5]. We evaluated the threshold modifications, Boolean 3- and 2-variable remission and the individual Boolean components. Figure 1 shows that the remission rates for 3-variable remission, DAS28(4), and DAS28(3) remained highest regardless of the PGA threshold used in 4-variable remission.

In a meta-analysis by Ferreira et al. (2020) [25], which included 12 studies reporting indirect 3-variable remission rates, a paper by Furu et al. [26] reported the highest 3-variable remission prevalence of 51% in a Japanese cohort in 2014. The average 3-variable remission prevalence from the 12 studies in the meta-analysis was 31% [25]. In other non-single-timepoint studies, Studenic et al. reported a 3-variable remission rate of 30% after 12 months of treatment for early RA [23]. Interestingly, a study of DMARD-naïve patients with early RA showed a similar remission rate when they were only treated with csDMARDs and prednisolone [27]. Our high 3-variable remission rate may be explained by the lower disease activity in our outpatient RA cohort (mean DAS28 2.4 and CDAI 6.4), where a high proportion of the patients (~ 40%) were treated with b/tsDMARDs.

When the 4-variable remission was divided into subjective (PGA, TJC28) and objective (CRP, SJC28) categories, only 25% of patients achieved subjective remission, whereas 76% reached objective remission. During the same year, among the one-variable cutoffs, PGA ≤ 10 had the lowest rate, 27%, the rate for TJC28 ≤ 1 was 74%, that for SJC28 ≤ 1 was 85%, and that for CRP ≤ 10 was the highest: 86%. We believe that these numbers reflect two valuable issues: (1) despite considering tender joints to be subjective, similar rates are reported for the objective SJC28 and CRP, and (2) there are considerable differences in rate between patients expressing PGA ≤ 10 and TJC28 ≤ 1, SJC28 ≤ 1, and CRP ≤ 10 (27% vs 74–86%).

Based on these numbers, remission-assessing methods that use PGA, at least for Boolean criteria, CDAI, and SDAI, do not appear favourable. The argument for including PGA was its ability to help differentiate active treatment from control treatment, which in turn meant a significant contribution to defining remission. Together with CDAI and SDAI, 4-variable remission was also considered to predict good radiographic outcomes [4]. In addition, PGA and CRP were considered a safeguard when using the standardized 28 joint count, which omits ankle and feet joints [4].

However, studies have shown that only swollen joints and acute phase reactants, not PGA, are robustly associated with radiographic progression [17, 23, 28]. This may further weaken the rationale for incorporating PGA into remission assessments, since stopping the progression of joint damage is one of the most important goals of RA treatment. With the introduction of modern imaging techniques, subclinical signs of inflammation have been demonstrated, highlighting the challenges of defining true remission in RA [29,30,31,32].

Moreover, RA patients in remission by any established criteria can experience radiographic progression [33]. A recent study showed that the increase in tender joints correlated best with other subjective variables (i.e. pain) but not with ultrasonographic synovitis, whereas swollen joints correlated significantly with ultrasonographic synovitis [34]. Furthermore, Hensor et al. found that a score based on SJC28 and CRP alone had a stronger association with ultrasonography synovitis and radiographic progression than the original DAS28 in early RA [35]. A recently published paper by Sundlisæter et al. (2022) observed no increase in inflammation measured with ultrasound and MRI in patients who failed to attain 4-variable remission due to PGA and/or TJC compared to those who achieved 4-variable remission [36]. Brites et al. (2021) did not observe any significant changes in inflammation on ultrasound either when comparing 4-variable remission and 3-variable remission [37]. This again supports the view that objective measures reflect inflammatory disease status better than subjective measures, which may also be impacted by noninflammatory mechanisms.

To distinguish between patients with treatment failure with and without the presence of objective inflammation, Buch and colleagues recently introduced the terms “persistent inflammatory refractory RA” (PIRRA) and “noninflammatory refractory RA” (NIRRA) [38]. Distinguishing between PIRRA and NIRRA from a clinical perspective is important, as the two require different treatments and treatment strategies. It is particularly relevant in patients who only fail to attain a 4-variable remission because PGA > 10 [38]. Real-life data, as collected in our study, are thus of great importance, as they reveal the strength and weaknesses of the present remission criteria when they are used to treat patients to remission in ordinary clinical practice.

In addition, the use of PGA in RA comes with numerous challenges due to its subjective and heterogeneous formulation. PGA is often a single unstandardized question with global-health-oriented or disease-activity-oriented wording. In our study, we used PGA with a more general description. Khan et al. showed that disease activity and general PGA could be used interchangeably for the calculation of RA activity when using CDAI, DAS28, and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 [39]. However, Gossec et al. reported discordance between the global-health-formulated and disease-activity-formulated PGA in Boolean remission for early arthritis patients [40]. PGA can also be expressed using various phrases or with an open question, where the answer is transformed to either a 0–10 or a 0–100 scale. Graphics can also be used, such as lines (horizontal or vertical) or tick marks with intervals [20]. In summary, numerous possible results increase the chance of generating various interpretations.

In the multivariable regression analyses, pain had the strongest and fatigue the second strongest association with PGA. When the analysis was based on disease activity, the strong association between pain and PGA was very similar for the subgroups. In the logistic regression assessment, these two variables were also only significant when compared with PGA-incorporated remission-assessing methods. Pain and fatigue are considered the leading sources of discomfort among RA patients and key contributing factors for reporting elevated PGA levels [20, 22, 41,42,43,44], especially in near-4-variable remission cases, i.e. in those who only failed to attain 4-variable remission because PGA > 10 [18, 24, 45]. The three most essential domains for achieving patient-perceived remission are pain, fatigue, and independence [46, 47]. From the patient's perspective, being in remission means reducing the impact of RA on their life, “eventually leading to a feeling of normality” [48].

Since PGA is strongly associated with the patient’s perception of pain, using remission methods impacted by PGA to guide medical treatment decisions when monitoring RA patients in an outpatient clinic may not reflect the inflammatory disease process. However, a less restrictive variant in which PGA has only a weak impact (DAS28 remission) can also cause the misestimation and omission of swollen joints.

This study should be seen in the context of its limitations. Like all observational studies, there are issues related to a certain level of missing data, confounding factors, and attrition bias. Only a selected group of patients without missing data were included. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, differences between the included and excluded patients were small and mostly nonsignificant, indicating a high grade of internal validity. Another limitation is the lack of radiographic data. The study's strengths are its real-life setting, the application of a spectrum of RA remission measurements, and the evaluation of PGA associations for relevant RA-related variables and remission definitions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study challenges the value of the currently used remission-assessing methods. Based on our results and available data, we suggest using methods without measures impacted by noninflammatory pain and psychosocial factors such as PGA when treating patients to remission with DMARDs. Interestingly, among all the variables used to assess the remission rate, only the IGA (used in both CDAI and SDAI) improved significantly, while the rest of the variables remained stable over the 5-year period.

Based on growing evidence, as supported by our study, we suggest that it may be time for a paradigm shift to develop new remission criteria and a new definition for use in ordinary clinical practice, with objective variables and imaging favoured to avoid treating noninflammatory pain with DMARDs.

References

Pinals RS, Masi AT, Larsen RA. Preliminary criteria for clinical remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24(10):1308–15.

Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, Burmester GR, Dougados M, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):685.

Mian A, Ibrahim F, Scott DL. A systematic review of guidelines for managing rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019;3:42.

Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LH, Funovits J, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):573–86.

Ferreira RJO, Welsing PMJ, Jacobs JWG, Gossec L, Ndosi M, Machado PM, et al. Revisiting the use of remission criteria for rheumatoid arthritis by excluding patient global assessment: an individual meta-analysis of 5792 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(3):293–303.

Pincus T, Summey JA, Soraci SA Jr, Wallston KA, Hummon NP. Assessment of patient satisfaction in activities of daily living using a modified Stanford health assessment questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26(11):1346–53.

Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, Kalden JR, Emery P, Eberl G, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(2):244–57.

Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, Uffmann M, Pflugbeil S, Machold K, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(4):R796-806.

Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):44–8.

Sokka T, Hetland ML, Mäkinen H, Kautiainen H, Hørslev-Petersen K, Luukkainen RK, et al. Remission and rheumatoid arthritis: data on patients receiving usual care in twenty-four countries. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(9):2642–51.

Thiele K, Huscher D, Bischoff S, Späthling-Mestekemper S, Backhaus M, Aringer M, et al. Performance of the 2011 ACR/EULAR preliminary remission criteria compared with DAS28 remission in unselected patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1194–9.

Mack ME, Hsia E, Aletaha D. Comparative assessment of the different American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism remission definitions for rheumatoid arthritis for their use as clinical trial end points. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):518–28.

Martins FM, da Silva JA, Santos MJ, Vieira-Sousa E, Duarte C, Santos H, et al. DAS28, CDAI and SDAI cut-offs do not translate the same information: results from the Rheumatic Diseases Portuguese Register Reuma.pt. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(2):286–91.

Medeiros MM, de Oliveira BM, de Cerqueira JV, Quixadá RT, de Oliveira ÍM. Correlation of rheumatoid arthritis activity indexes (Disease Activity Score 28 measured with ESR and CRP, Simplified Disease Activity Index and Clinical Disease Activity Index) and agreement of disease activity states with various cut-off points in a northeastern Brazilian population. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2015;55(6):477–84.

Aletaha D, Wang X, Zhong S, Florentinus S, Monastiriakos K, Smolen JS. Differences in disease activity measures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who achieved DAS, SDAI, or CDAI remission but not Boolean remission. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(2):276–84.

Xie W, Li J, Zhang Z. The impact of different criteria sets on early remission and identifying its predictors in rheumatoid arthritis: results from an observational cohort (2009–2018). Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(2):381–9.

Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis progresses in remission according to the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints and is driven by residual swollen joints. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3702–11.

Studenic P, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Near misses of ACR/EULAR criteria for remission: effects of patient global assessment in Boolean and index-based definitions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(10):1702–5.

Fusama M, Miura Y, Yukioka K, Kuroiwa T, Yukioka C, Inoue M, et al. Psychological state is related to the remission of the Boolean-based definition of patient global assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(5):679–82.

Nikiphorou E, Radner H, Chatzidionysiou K, Desthieux C, Zabalan C, van Eijk-Hustings Y, et al. Patient global assessment in measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the literature. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):251.

Radner H, Yoshida K, Tedeschi S, Studenic P, Frits M, Iannaccone C, et al. Different rating of global rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients with multiple morbidities. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(4):720–7.

Inanc N, Yilmaz-Oner S, Can M, Sokka T, Direskeneli H. The role of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and fibromyalgia on the evaluation of the remission status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(9):1755–60.

Studenic P, Felson D, de Wit M, Alasti F, Stamm TA, Smolen JS, et al. Testing different thresholds for patient global assessment in defining remission for rheumatoid arthritis: are the current ACR/EULAR Boolean criteria optimal? Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(4):445–52.

Ferreira RJO, Duarte C, Ndosi M, de Wit M, Gossec L, da Silva JAP. Suppressing inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis: does patient global assessment blur the target? A practice-based call for a paradigm change. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(3):369–78.

Ferreira RJO, Santos E, Gossec L, da Silva JAP. The patient global assessment in RA precludes the majority of patients otherwise in remission to reach this status in clinical practice. Should we continue to ignore this? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(4):583–5.

Furu M, Hashimoto M, Ito H, Fujii T, Terao C, Yamakawa N, et al. Discordance and accordance between patient’s and physician’s assessments in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;43(4):291–5.

Rannio T, Asikainen J, Kokko A, Hannonen P, Sokka T. Early remission is a realistic target in a majority of patients with DMARD-naive rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(4):699–706.

Navarro-Compán V, Gherghe AM, Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Landewé R, van der Heijde D. Relationship between disease activity indices and their individual components and radiographic progression in RA: a systematic literature review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(6):994–1007.

Brown AK, Quinn MA, Karim Z, Conaghan PG, Peterfy CG, Hensor E, et al. Presence of significant synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis patients with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-induced clinical remission: evidence from an imaging study may explain structural progression. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3761–73.

Brown AK, Conaghan PG, Karim Z, Quinn MA, Ikeda K, Peterfy CG, et al. An explanation for the apparent dissociation between clinical remission and continued structural deterioration in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):2958–67.

Gandjbakhch F, Conaghan PG, Ejbjerg B, Haavardsholm EA, Foltz V, Brown AK, et al. Synovitis and osteitis are very frequent in rheumatoid arthritis clinical remission: results from an MRI study of 294 patients in clinical remission or low disease activity state. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(9):2039–44.

Gandjbakhch F, Haavardsholm E, Conaghan P, Ejbjerg B, Foltz V, Brown A, et al. Determining a magnetic resonance imaging inflammatory activity acceptable state without subsequent radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a followup MRI study of 254 patients in clinical remission or low disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(2):398–406.

Lillegraven S, Prince FH, Shadick NA, Bykerk VP, Lu B, Frits ML, et al. Remission and radiographic outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: application of the 2011 ACR/EULAR remission criteria in an observational cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(5):681–6.

Hammer HB, Jensen Hansen IM, Järvinen P, Leirisalo-Repo M, Ziegelasch M, Agular B, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients with predominantly tender joints rarely achieve clinical remission despite being in ultrasound remission. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2021;5(2):rkab030.

Hensor EMA, McKeigue P, Ling SF, Colombo M, Barrett JH, Nam JL, et al. Validity of a two-component imaging-derived disease activity score for improved assessment of synovitis in early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(8):1400–9.

Paulshus Sundlisæter N, Sundin U, Aga AB, Sexton J, Hammer HB, Uhlig T, et al. Inflammation and biologic therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis achieving versus not achieving ACR/EULAR Boolean remission in a treat-to-target study. RMD Open. 2022;8(1):e002013.

Brites L, Rovisco J, Costa F, Freitas JPD, Jesus D, Eugénio G, et al. High patient global assessment scores in patients with rheumatoid arthritis otherwise in remission do not reflect subclinical inflammation. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88(6): 105242.

Buch MH, Eyre S, McGonagle D. Persistent inflammatory and non-inflammatory mechanisms in refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(1):17–33.

Khan NA, Spencer HJ, Abda EA, Alten R, Pohl C, Ancuta C, et al. Patient’s global assessment of disease activity and patient’s assessment of general health for rheumatoid arthritis activity assessment: are they equivalent? Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(12):1942–9.

Gossec L, Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Balanescu A, Gaujoux-Viala C, Guillemin F, et al. Phrasing of the patient global assessment in the rheumatoid arthritis ACR/EULAR remission criteria: an analysis of 967 patients from two databases of early and established rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(6):1503–10.

Studenic P, Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Discrepancies between patients and physicians in their perceptions of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(9):2814–23.

Egsmose EL, Madsen OR. Interplay between patient global assessment, pain, and fatigue and influence of other clinical disease activity measures in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(7):1187–94.

Ward MM, Guthrie LC, Dasgupta A. Direct and indirect determinants of the patient global assessment in rheumatoid arthritis: differences by level of disease activity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(3):323–9.

Karpouzas GA, Strand V, Ormseth SR. Latent profile analysis approach to the relationship between patient and physician global assessments of rheumatoid arthritis activity. RMD Open. 2018;4(1): e000695.

Ferreira RJO, Dougados M, Kirwan JR, Duarte C, de Wit M, Soubrier M, et al. Drivers of patient global assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who are close to remission: an analysis of 1588 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(9):1573–8.

Rasch LA, Boers M, Hill CL, Voshaar M, Hoogland W, de Wit M, et al. Validating rheumatoid arthritis remission using the patients’ perspective: results from a special interest group at OMERACT 2016. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(12):1889–93.

van Tuyl LH, Sadlonova M, Hewlett S, Davis B, Flurey C, Goel N, et al. The patient perspective on absence of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey to identify key domains of patient-perceived remission. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(5):855–61.

Van Tuyl L, Hewlett S, Sadlonova M, Davis B, Flurey C, Hoogland W, et al. The patient perspective on remission in rheumatoid arthritis: ‘You’ve got limits, but you're back to being you again’. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1004–10.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Editorial Assistance

We share our gratitude to the proof-reading company (https://www.proof-reading-service.com) for their evaluation.

Authorship

All authors fulfil the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article. All authors have given their consent to submit and publish the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Alen Brkic, Katarzyna Łosińska, Are Hugo Pripp, Mariusz Korkosz, and Glenn Haugeberg were involved in the conception, design, and interpretation of data. Alen Brkic was mainly responsible for drafting the manuscript and analysing the data, with contributions from Katarzyna Łosińska, Are Hugo Pripp, Mariusz Korkosz, and Glenn Haugeberg. All authors critically reviewed the results and contributed to the interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Alen Brkic, Katarzyna Łosińska, Are Hugo Pripp, Mariusz Korkosz, and Glenn Haugeberg have nothing to disclose. They have no financial interests that could create a potential conflict of interest or the appearance of a conflict of interest concerning the submitted work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (REC) of Middle Norway (2010/3078) and followed the ethical principles of medical research involving human subjects of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki (and its later amendments). No consent from patients was required by the REC of Middle Norway, as all data were anonymized and collected as part of routine clinical care.

Data Availability

Data are available on reasonable request and must be approved by all participating centres.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brkic, A., Łosińska, K., Pripp, A.H. et al. Remission or Not Remission, That’s the Question: Shedding Light on Remission and the Impact of Objective and Subjective Measures Reflecting Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol Ther 9, 1531–1547 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00490-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00490-5