Abstract

Introduction

In Brazil, patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) have access to free-of-charge comprehensive therapeutic care through the Brazilian National Health System. We collected prospective data on patients with AS receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy through the Brazilian National Health System in Belo Horizonte City in order to evaluate the effectiveness, quality-of-life outcomes and safety of this therapy.

Methods

This was a prospective study that included 87 patients receiving their first course of anti-TNF agents (adalimumab, etanercept or infliximab). The effectiveness of treatment was assessed at 6 and 12 months of follow-up using measures of disease activity [Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)], function [Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)] and quality of life (EuroQol-5D). Good clinical response was defined as an improvement of at least 50% or 2 units in the BASDAI. Episodes of adverse events were recorded. Logistic regression was performed, and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated to estimate predictors of good clinical response at 6 months.

Results

At 6 months of follow-up, 64.9% of patients had a good clinical response, as evidenced by a drop in the median BASDAI score from 5.21 to 2.50 (p < 0.0001) and a reduction in the HAQ score from 1.13 to 0.38 (p < 0.0001). Patients also showed an improvement in health-related quality of life which was sustained after 12 months of follow-up. Female patients achieved a significantly lower clinical response than male patients (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.11–0.78), but we observed no significant associations between the other variables. At the end of the study, 93 non-serious adverse events had been reported.

Conclusion

Treatment with the anti-TNF drugs adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab is effective and well tolerated in patients with AS. The improvement in disease activity, functional parameters and quality of life was sustained for 12 months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease that mainly affects the spine. Patients with AS can experience progressive stiffness and functional limitation of the axial skeleton, with subsequent increasing disability and a reduced quality of life [1, 2]. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) drugs are recommended as therapy for patients with high disease activity despite the first-line treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [3]. Randomized clinical trials and observational studies have shown that patients treated with anti-TNF agents experience a decrease in disease activity and better functionality [4]. The National Register for Biologic Treatment in Finland (ROB-FIN) reported that 52% of patients receiving anti-TNF therapy achieved 50% improvement on the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) after 6 months [5]; the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register reported a very similar outcome in 50% of patients [6].

Evaluations on the impact of long-term use of these drugs in real life settings are required because the impact of anti-TNF therapy on patients may differ from that seen in clinical trials, which usually have short follow-up periods and selection criteria that restrict patients with comorbidities and concomitant drugs. The Brazilian Registration of Spondyloarthritis and the Brazilian Biologic Registry (BIOBADA BRASIL) collects epidemiological and clinical data on the exposure of patients to anti-TNF drugs [7, 8]. However, little is known to date on the effectiveness and quality-of-life outcomes in Brazilian AS patients receiving anti-TNF therapy.

The BIOBADA BRASIL estimated that 400 patients with AS started anti-TNF therapy in 2009 [7]. In 2010, the Brazilian National Health System (SUS) made available the anti-TNF drugs infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab through the Specialised Drug Program which targets drugs used in later stages of treatment of several diseases. The SUS offers free-of-charge access to comprehensive therapeutic care to all Brazilian citizens. In Brazil, there is a mix of public (SUS) and private healthcare services, with 25% of the population having private health insurance. However, those with private healthcare insurance are also eligible to access SUS services, especially in cases where high-cost medicines are not covered by their insurance plan [9]. The inclusion of anti-TNF agents in the SUS may have increased patient access to these drugs in Brazil. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness, including health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and safety of the first course of anti-TNF therapy and the predictors of good clinical response in AS patients treated through the auspices of the SUS in Belo Horizonte City, Brazil.

Methods

This was an open prospective study involving patients with AS who had received anti-TNF therapy in Belo Horizonte City, Brazil, from August 2011 to November 2014. Adult patients whose request for treatment with the anti-TNF drugs infliximab, etanercept or adalimumab had been approved by the Specialised Drug Program were invited to participate. According to the Brazilian Therapeutic Guideline, treatment with these anti-TNF drugs is only approved in patients with AS as defined by the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) classification criteria or by the modified New York criteria (established AS) and persistent high disease activity (BASDAI score ≥4) despite the use of two different NSAIDs for 3 months. The recommended doses are etanercept 50 mg once weekly; infliximab 5 mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 weeks and 8 weekly interval thereafter; adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks [10]. Only patients who had started their first course of anti-TNF therapy (naïve to anti-TNF drugs) were included in the study; those with previous use of these drugs were excluded from entry. The index date of follow-up was the day of first dispensation of the anti-TNF agent. The assessments took place at the pharmacies of the Specialised Drug Program at baseline and at 6 and 12 months thereafter.

We recorded socio-demographic variables (such as age, gender, education level, marital status and self-reported race) and assessed the period of time from diagnosis, self-reported comorbidities, previous and current medication for AS, Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA), BASDAI and number of patients who achieved good clinical response. Good clinical response was defined as an improvement in the BASDAI score by at least 50% or by 2 units. The scores were measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS) of 0–10. Functionality and the HRQoL were assessed by the Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ) [11, 12] and by the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D), respectively. The generic EQ-5D questionnaire includes five dimensions of health addressing mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression and provides a summary of health utility scores derived from a study performed in Minas Gerais state (Belo Horizonte is the capital of Minas Gerais state) [13]. It also contains a vertical VAS ranging from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state) [14]. Episodes of adverse events were also recorded.

We calculated the frequency distributions for categorical variables and the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. In addition to determining the overall BASDAI score, we described its components separately: fatigue, spinal pain, pain and swelling peripheral joints, enthesitis, and duration of morning stiffness. We compared baseline assessments among patients with a baseline BASDAI ≥4 and BASDAI <4 and applied Student’s t test when the values were normally distributed and the Mann–Whitney test otherwise. We compared clinical outcomes at baseline and at 6 and 12 months of follow-up and applied the paired Student’s t test when the results were normally distributed and the Wilcoxon signed rank sum test otherwise. Logistic regression and odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were used to identify predictor factors associated with good clinical response at 6 months. The duration of disease, baseline PtGA, HAQ, EQ-5D, EQ-5D VAS, fatigue, spinal pain, pain and swelling peripheral joints, enthesitis and duration of morning stiffness were included as continuous variables, whereas age (quartiles), gender, education, race, type of anti-TNF therapy, baseline use of NSAIDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and corticosteroid were included as categorical variables. Only statistically significant variables were retained in the final model by the stepwise-backward method. We adopted a significance level of 5%, and the statistical analyzes were performed using SAS version 9.4 for UNIX (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil (ETIC 0069.0.203.000-10). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for inclusion in the study.

Results

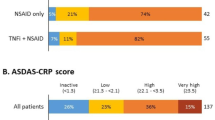

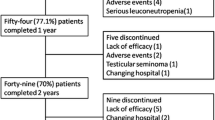

Our initial survey identified 98 patients with AS who had received therapy with the anti-TNF agents infliximab, etanercept or adalimumab and initiated follow-up during the study period. Of these, 11 had a prior history of anti-TNF therapy and were excluded from entry. The final patient cohort therefore included 87 patients, of whom 63 and 32 completed 6 and 12 months of follow-up, respectively. The reason for withdraw was not addressed. The characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. Most patients were male (63.3%), the median age was 41.0 (IQR 31.9–51.3) years and the median disease duration was 4.5 (IQR 1.0–12.0) years. At baseline, 36.8% patients were using corticosteroids, 35.6% were using NSAIDs and 27.6% were using DMARDs (mainly methotrexate); during the follow-up, the frequency of concomitant therapy dropped (Table 2).

At baseline, 64 (73.6%) patients had a BASDAI score of ≥4. Compared to patients with a BASDAI score of <4, these patients had a longer disease duration (p = 0.0266; Table 1), worse assessment on the PtGA, HAQ and EQ-5D (p < 0.0005), and similar EQ-5D VAS (p = 0.1700) (data not shown). Among patients with a baseline BASDAI score of ≥4, 63.1 and 64.7% achieved a BASDAI score of <4 at 6 and 12 months, respectively.

At 6 months of follow-up, 64.9% of patients achieved a good clinical response. The reductions in both the median PtGA score from 6.90 (IQR 3.80–8.70) at baseline to 3.20 [IQR 0.80–6.60 at 6 months (p < 0.0001)] and the median BASDAI score from 5.21 (IQR 3.79–6.61) at baseline to 2.50 (IQR 0.99–4.48) at 6 months (p < 0.0001) were statistically significant. The scores for fatigue, spinal pain, pain and swelling peripheral joints, enthesitis and duration of morning stiffness also decreased from baseline. Of 26 patients who were assessed at 12 months, 65.4% had achieved a good clinical response, with reduced scores for PtGA, BASDAI, spinal pain, enthesitis, and duration of morning stiffness compared to baseline. Changes in the fatigue and pain and swelling peripheral joints scores, however, were not statistically significant. An improvement in functionality and HRQoL was achieved at 6 months and maintained after 12 months of therapy. After 6 months, the median value of the HAQ decreased from 1.13 (IQR 0.63–1.50) at baseline to 0.38 [IQR 0.13–1.13 (p < 0.0001)] (Table 3). In the final multivariate model, female gender was associated with a worse clinical response (OR 0.29, 95% CI 0.11–0.78; p = 0.0141); the other covariates were not significant (Table 4).

At the end of the study, 93 adverse events had been reported by 56 (57.1%) patients, with the most common being headache (16.1%), influenza (14.1%) and application site reaction (14.0%). A number of cases of infection were observed, including five urinary tract infections, three upper respiratory infections and two fungal infections (Table 5).

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate patients with AS who were treated with anti-TNF through the assistance of a public drug program in Brazil. Our study followed-up patients who were diagnosed with AS according to the Brazilian Therapeutic Guideline and treated with anti-TNF drugs in the city of Belo Horizonte. All patients enrolled in the study were from a real-life clinical setting. Our findings showed an improvement in disease activity, functionality and HRQoL after 6 months of anti-TNF therapy and sustained benefits within 12 months, with the exception of fatigue and pain and swelling peripheral joints. After 12 months of follow-up, 65.4% of patients achieved a good clinical response, with a median reduction in the BASDAI and HAQ scores of 2.28 and 0.56, respectively.

The selection of the most appropriate therapeutic option for use in clinical practice should be based on effectiveness, safety, convenience and cost. It is essential that the decision-making process be based on evidence acquired in studies which have applied the systematic and appropriate methods for each type of question. Within this framework, our results provide good evidence for the effectiveness of anti-TNF therapy in AS patients. Our evaluation of the clinical effectiveness of the patients is that the Braziian Specialised Drug Program has adopted an efficient and a valuable strategy to bring therapeutic benefits to the Brazilian patient population and to increase access to high-cost drugs.

Our results are in agreement with those of previous studies and indicate that adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab are effective agents to treat AS. Both the Finnish and British registers reported that approximately one-half of their patients with AS achieved 50% improvement on BASDAI at 6 months of follow-up. Patients from the British Register were also reported to have achieved improvement in their Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) score (mean change −2.6), C-reactive protein (CRP) level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) at 6 months [5, 6]. The Danish Nationwide Rheumatological Database (DANBIO) Register reported that 63% of AS patients achieved a 50% improvement or a reduction of 2 units on the BASDAI up to 6 months of therapy and that the BASDAI score fell from a median baseline value of 5.9 to a median value of 2.6 at 6 months, and then to 21 at 12 months. A clinical response was also observed for BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), pain and fatigue and was sustained more than 5 years [15]. Other studies have evaluated the HRQoL using the Short Form 36 (SF36) and found clinical improvement after 4 and 6 months of etanercept and infliximab therapy [16, 17].

In our patient cohort, male gender was a good predictor of clinical response. Another Brazilian study involving patients with spondyloarthritis reported that female gender was associated with more painful and swollen joints and higher BASDAI and BASFI scores [18]. An Italian study found that male AS patients had higher chances of achieving a partial remission response after 12 months of anti-TNF therapy than female AS patients (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.09–3.84), but that after 24 months the difference was not significant (OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.60–3.04) [19]. In contrast, the Danish Registry found a non-significant association with gender [15]. Fibromyalgia affects 15% of AS patients in a male:female ratio of 1:3, and its symptoms of morning stiffness, fatigue and pain can lead to a confounding effect in the disease activity measure with BASDAI [18, 20, 21]. We found that concomitant baseline therapy with NSAIDs, corticosteroids or DMARDs did not affect the clinical response and that the proportion of patients in combination therapy with these drugs had decreased after 6 and 12 months of follow-up. It is most likely that treatment with the anti-TNF agent played a major role in relieving the symptoms in our patients. However, the question of whether or not anti-TNF + DMARD combination therapy is a predictor of good clinical response is still open to debate, and the answer likely depends on the magnitude of peripheral joint involvement of the AS patients. Other studies have reported that younger age, higher levels of ESR and CRP, lower baseline BASFI score and higher baseline BASDAI score are associated with BASDAI-50 response, whereas the variables of anti-TNF drug and disease duration did not reach statistical significance [6, 15].

In our study, 36.8% of patients were using corticosteroids on baseline and 26.9% were still using corticosteroids after 12 months of follow-up, probably to treat peripheral or extra-articular manifestations, since the use of corticosteroids for axial disease is not supported by current evidence [3, 22]. However, we could not confirm this supposition because we did not address the reasons for corticosteroid use in our study. The frequency of corticosteroid use among patients with AS has been found to be lower in other studies, ranging from 15 to 30% at the start anti-TNF therapy [5, 6]. Thus, our results should raise awareness of the potential for the irrational prescribing and use of these drugs given the risks associated with their chronic use.

The anti-TNF therapy was well tolerated, with patients reporting primarily minor adverse events and few infections. The BIOBADA BRASIL reported that one-third of AS patients discontinued therapy due to adverse effects [23], and Glintborg et al. [15] reported a similar rate among Danish patients. Conversely, other studies have reported that adverse events were the major reason for drug discontinuation [24, 25].

In our study, one-fourth of patients had a baseline BASDAI score of <4, which means that they did not meet the inclusion criteria of the Brazilian Therapeutic Guideline to start anti-TNF therapy [10]. This may indicate that there is a trend in Brazil towards initiating anti-TNF therapy in an earlier stage of disease, which in turn opens up the discussion on heathcare providers’ awareness of and compliance to the Brazilian recommendations and whether the early initiation of anti-TNF therapy in AS patients is reasonable. Indeed, results from the Norwegian Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drug (NOR-DMARD) register shows that baseline disease activity scores, CRP and disease duration decreased significantly from 2002 to 2011 among patients with axial spondyloarthritis initiating biological therapy [26].

One limitation of our study relates to the method applied to contact the patients. Only those who visited the specified pharmacies were eligible to participate in the study and to be followed-up at 6 and 12 months. The drug can be dispensed for a family member if the patient is not able to attend the pharmacy; thus, patients with severe AS may not have been included in the study and/or may have withdrawn during the follow-up, which could have biased the number of reports of serious adverse events. Throughout the study period, the waiting time for medication dispensing at the pharmacies became shorter due to improvements in organization. As patients were frequently assessed while they were waiting for their medication dispensing, the better organization may have resulted in fewer patients being willing to be interviewed. This potential for decrease in the number of patients being interviewed together with the commonly known reasons of therapy discontinuation, such as loss of efficacy and adverse events, could have contributed to the high withdraw rate observed at the 12-month follow-up [15, 18]. Other studies have shown that the 1-year anti-TNF drug survival can range between 70% and 83% among AS patients [27, 28].

The lack of access to the clinical data for a number of patients is also a limiting factor in our study. These patients had the diagnosis of AS confirmed by their physician in accordance with the criteria of the Brazilian Therapeutic Guideline, but additional information on their clinical status was unavailable. We also were unable to determine the motivation underlying the initiation of anti-TNF therapy in patients with a BASDAI score of <4. In addition, laboratory indices, such as CRP, ESR and positivity for HLA-B27, were not assessed in our study.

Conclusion

Our results show that anti-TNF therapy is very effective in treating AS and that it is well tolerated among patients enrolled in our study. The improvement in disease activity, functionality and quality of life was good and sustained for 12 months. Baseline concurrent DMARD treatment was not found to be a predictor of good clinical response. Men achieved better outcomes than women. Our findings help to translate clinical trial results into the benefits observed in real life settings and reinforce the results found in literature. Furthermore, our investigation contributes valuable information in terms of improving our understanding of the profile and therapy outcomes of patients assisted by the Specialized Drug Program in Brazil. Our results provide relevant evidence to support decisions made by physicians, healthcare providers, and policymakers that can help to improve health care at both the individual and population levels. Further studies should focus on evaluating the benefits of switching between biologics and applying the health utility score obtained by EQ-5D in economic analyses.

References

Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369:1379–90.

Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(6):857–72.

Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X, et al. 2010 Update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):896–904.

Machado MA, Barbosa MM, Almeida AM, et al. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with TNF blockers: a meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(9):2199–213.

Heinonen AV, Aaltonen KJ, Joensuu JT, Lähteenmäki JP, Pertovaara MI, Romu MK, et al. Effectiveness and drug survival of TNF inhibitors in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a prospective cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(12):2339–46.

Lord PA, Farragher TM, Lunt M, et al. Predictors of response to anti-TNF therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Rheumatology. 2010;49(3):563–70.

Titton DC, Silveira IG, Louzada-Junior P, et al. Brazilian biologic registry: Biobada Brasil implementation process and preliminary results. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51(2):152–60.

Kohem CL, Bortoluzzo AB, Gonçalves CR. Profile of the use of disease modifying drugs in the Brazilian Registry of Spondyloarthritides. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2014;54(1):33–7.

Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, et al. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1778–97.

Brasil Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Portaria nº 640, de 24 de julho de 2014. Aprova o Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas da Espondilite Ancilosante; 2014. http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2014/julho/25/pcdt-espondilite-ancilosante-2014.pdf. Accessed 22 Dec, 2014.

Ferraz MB, Oliveira LM, Araujo PMP, et al. Crosscultural reliability of the physical ability dimension of the health assessment questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:813–7.

Shinjo SK, Gonçalves R, Kowalski S, Gonçalves CR. Brazilian-Portuguese version of the Health Assessment Questionnaire for Spondyloarthropathies (HAQ-S) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(8):1254–8.

Andrade MV, Noronha K, Kind P, et al. Societal preferences for EQ-5D health states from a Brazilian population survey. Value Health Reg Issues. 2013;2(3):405–12.

Euroqol Group. EQ-5D a measure of health-related quality of life developed by the EuroQol group: user guide. 7th ed. Rotterdam: EuroQol Group; 2000.

Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS, et al. Predictors of treatment response and drug continuation in 842 patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor: results from 8 years’ surveillance in the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):2002–8.

Saeed A, Khan M, Elmamoun M, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis in Ireland: patient access and response to TNF-α blockers. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(5):1305–9.

Heiberg MS, Nordvåg BY, Mikkelsen K, et al. The comparative effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor-blocking agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a six-month, longitudinal, observational, multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2506–12.

de Carvalho HM, Bortoluzzo AB, Gonçalves CR, et al. Brazilian Registry on Spondyloarthritis. Gender characterization in a large series of Brazilian patients with spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(4):687–95.

Perrotta FM, Addimanda O, Ramonda R, et al. Predictive factors for partial remission according to the Ankylosing Spondylitis Assessment Study working group in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-TNFα drugs. Reumatismo. 2014;66(3):208–14.

Azevedo VF, Paiva ED, Felippe LRH, Moreira RA. Occurrence of fibromyalgia in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2010;50(6):646–50.

Salaffi F, De Angelis R, Carotti M, Gutierrez M, Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F. Fibromyalgia in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: epidemiological profile and effect on measures of disease activity. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(8):1103–10.

El Maghraoui A. Extra-articular manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis: prevalence, characteristics and therapeutic implications. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(6):554–60.

Fafá BP, Louzada-Junior P, Titton DC, et al. Drug survival and causes of discontinuation of the first anti-TNF in ankylosing spondylitis compared with rheumatoid arthritis: analysis from BIOBADABRASIL. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34(5):921–7.

Heiberg MS, Koldingsnes W, Mikkelsen K, et al. The comparative one-year performance of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: results from a longitudinal, observational, multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:234–40.

Carmona L, Gómez-Reino JJ. Survival of TNF antagonists in spondylarthritis is better than in rheumatoid arthritis. Data from the Spanish registry BIOBADASER. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R72.

Lie E, Fagerli KM, Mikkelsen K, et al. First-time prescriptions of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis 2002–2011: data from the NOR-DMARD register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(10):1905–6.

Navarro-Millán I, Sattui SE, Curtis JR. Systematic review of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor discontinuation studies in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2013;35(11):1850–61.

Nell-Duxneuner V, Schroeder Y, Reichardt B, Bucsics A. The use of TNF-inhibitors in ankylosing spondylitis in Austria from 2007 to 2009—a retrospective analysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50(12):867–72.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored and funded by the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq–64778/2010-9). All of the authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship of this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval to the version to be published.

The authors acknowledge the collaboration of members of the Research Group on Pharmacoepidemiology of Federal University of Minas Gerais and of the pharmacies where the study was performed.

Disclosures

All of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil (ETIC 0069.0.203.000-10). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

de Machado, M.A.d., Almeida, A.M., Kakehasi, A.M. et al. Real Life Experience of First Course of Anti-TNF Treatment in Ankylosing Spondylitis Patients in Brazil. Rheumatol Ther 3, 143–154 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-016-0026-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-016-0026-2