Abstract

Mobile learning has expanded the reach of electronic and distance education, which has been made possible by modern technology and globalization. There is a need to identify the elements that are essential in determining behavioral intention towards mobile learning because there is a dearth of scientific justification for their importance. The goal of the study is to ascertain how behavioral intention towards mobile learning are affected by perceived entertainment, perceived informativeness, perceived irritation, perceived trust, and perceived value. Moreover, the study examines the mediating role of attitude among the aforementioned variables and behavioral intention towards mobile learning. Finally, the moderating impact of social influence on the relationship between attitude and behavioral intention towards mobile learning is investigated. The multistage cluster sampling technique is used to gather data from 586 students. Multiple regression analysis is utilized to test hypotheses, whereas AMOS-23 is used for confirmatory factor analysis. Hayes & Preacher’s macro is applied to assess mediation and moderation. The results show that perceived entertainment, informativeness, trust, and value significantly and directly influence attitude towards mobile learning, but perceived irritation has a negative effect. Additionally, perceived entertainment, trust, and value have a direct and significant impact on behavioral intention towards mobile learning, whereas perceived irritation has a negative and informativeness has an insignificant impact. Finally, the attitude is supported as a mediator, while social influence confirms its role as a moderator. The study offers significant theoretical and practical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mobile learning is learning conducted outside of the classroom using mobile devices (Reychav et al., 2016). It is a learning that takes place on portable electronic devices, including smartphones, tablets, MP3 (music parameter) players, and all other mobile gadgets (Tan et al., 2014). Mobile learning is expected to play a significant role in many educational settings that provide students with timely and appropriate directions. Online learning is replacing traditional classroom teaching in the educational process, but it still depends on accurate information, appropriate delivery, and opportunity (Milosevic et al., 2015; Sophonhiranrak, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has made things worse and increased interest in mobile learning. Challenges are being faced by educational institutions worldwide as a result of this pandemic, and fewer students are taking exams (Alturki & Aldraiweesh, 2022). At the moment, educational institutions are fully accountable for implementing novel teaching methods and procedures (Naciri et al., 2020).

Informal education and the use of mobile technologies for education have both seen significant development. As mobile technology and the internet are combined, there is an increase in communication and learning engagement. The use of smartphones and tablets are a fundamentally beneficial addition to accessing educational resources due to the acceptability of mobile technology as a new tool for learning purpose by students (Al-Bashayreh et al., 2022). The adaptability of modern technology has both direct and indirect effects on how well students learn. Though mobile learning is fast expanding globally due to mobile technologies particularly designed for educational purposes, the research on behavioral intention toward mobile learning is still in its infancy (Naciri et al., 2020; Criollo-C, 2021). Zeithaml (1988) defined behavioral intention as the customer’s future conduct based on his or her subjective assessment and generally classified it into favorable and unfavorable behavioral intentions. In the past, behavioral intention has been extensively researched with the inclusion of a variety of variables, such as intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Feng et al., 2016), adoption of mobile technologies (Sanakulov & Karjaluoto, 2015), trust (Luo et al., 2010), word of mouth, image and attitude (Jalilvand et al., 2012), and social norm (McDonald & Crandall, 2015). The potential for behavioral intention toward mobile learning in higher education is enormous given the development of technology, as shown by previous rearches (Prieto et al., 2015; Criollo-C et al., 2021; Humida et al., 2022). However, it is stated that the development of behavioral intentions toward mobile learning (BITML) is not straightforward and that a number of significant factors, including perceived entertainment, informativeness, irritation, trust, and value, may have an impact. Although it is thought to be one of the paradigms that is most rapidly changing, such a combination of factors has previously been overlooked (Chen, 2011; Viberg & Gronlund, 2013; Cheok & Wong, 2015; Mohammadi, 2015a, 2015b, 2015c; Reychav & Wu, 2015; Wong et al., 2015).

Furthermore, it is essential to comprehend the underlying mechanisms by which behavioral intentions toward mobile learning (BITML) may be influenced by perceived entertainment, informativeness, irritation, trust, and value. The extant literature indicates that attitude mediates the association between a variety of predictors, such as entertainment, relaxation, escape time, value, and quality, and dependent variables, such as behavioral intention, purchase intention, and buying intention (Curras-Perez et al., 2014; Hameed et al., 2018; Mohammadi, 2015a; Zhu & Chang, 2014); however, mediating role of attitude between perceived entertainment, informativeness, irritation, trust and value, and BITML has not been explored yet. Therefore, in order to provide a more comprehensive picture, this study aims to investigate the impact of the five factors described above on attitude toward mobile learning (ATML), which in turn influences BITML and mediating role of ATML between relathionship of entertainment (ENT), informativeness (INF), irritation (IRR), trust (PERT), value (PERV), and BITML.

Numerous studies have looked into the connection between social influence and behavioral intention in the past (Contractor & DeChurch, 2014; Jung et al., 2016; Yang Lu et al., 2012). Because the social group gives compelling information regarding a product’s suitability and aids in decision-making, social influence lowers the risk of adoption (Alzaidi & Shehawy, 2022). Most people are not impacted by the media, but the peer group they are surrounded by has a big effect on their decision-making process. In the age of technology and mobile education, however, the moderating impact of social influence (SI) on the relationship between attitude and behavioral intentions toward mobile learning is comparatively understudied. Thus, another purpose of the study is to ascertain how social influence moderates the said relationship.

Literature review

Theoretical foundation

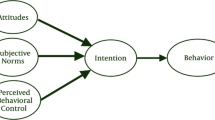

The relationship of behavioral intention toward mobile learning is based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The TPB declares that “behavior is a direct function of behavioral intention and perceived behavioral intention is formed by one’s attitude which reflects the feeling of favorableness or unfavorableness toward performing a certain behavior.” Previous literature showed that TPB has been used in various types of research to measure the planned behavior, attitude, and intentions toward mobile learning as mandated by Kolog et al., (2014) and Lee et al., (2015a, 2015b). Secondly, User & Gratification (U&G) theory has been used to evaluate the BITML. Blumler and Katz (1974) established the concept of mass media communication, which was based on a functionalist perspective. This hypothesis is employed in the media paradigm, which asks “why people use certain media and what gratifications they obtain from media access.” The theory is valuable for studies involving active media users because it incorporates the user’s psychological and social demands, which illuminate “how and why individuals choose to utilize specific media” (Kim Xu, & Gupta, 2012). As a result, mobile learning satisfies the U&G assumptions because U&G asks “what people do with media, not what media do to people,” it is particularly well suited to mobile learning research, which has the potential for both interpersonal and mass communication (Chen, 2011; Johnson & Yang, 2009; Reychav & Wu, 2015). The U&G theory has numerous fundamental constructs and various typologies have been used in different years to explore the effects with different mediums. The literature showed that the most prominent and frequently used dimensions include entertainment, informativeness, and irritation (Chen & Wells, 1999; Eighmey & McCord, 1998; Fenech, 1998; Korgaonkar & Wolin, 1999; Lim & Ting, 2012). Thus, in the present study for determining BITML, three antecedents of U&G theory have been considered, i.e., entertainment, informativeness, and irritation.

Behavioral intention toward mobile learning

BITML is evolving concept as mandated by Humida, (2022) with the increased use of smartphones. The advancement of technology has benefited the education sector and various studies have been undertaken from the perspective of students to analyze the success elements of the notion of mobile learning. Mobile learning has introduced new strategies that are significantly superior to those offered by electronic learning (i.e., time and space flexibility). Mobile learning presents enormous prospects in higher education as technology advances, and past study has shown a lot of interest in this field. Prieto et al., (2015) have expanded on the idea that mobile devices have become increasingly important in the teaching and learning process in recent years. In the realm of informal education and mobile technologies for educational purposes, mobile learning is well established and when mobile technology is combined with the internet, it has enhanced communication and learning engagement. Smartphones and tablets are extremely useful tools for accessing instructional resources (Al-Bashayreh, 2022). Mobile learning provides students with timely and suitable guidance and in a variety of educational settings, mobile learning is projected to play a key role that may affect behavioral intentions. Several factors can influence students’ deliberate conduct when it comes to mobile learning. It is not a choice; rather, it is a necessity for keeping up with evolving technology and innovation. Students may easily and rapidly access and use learning tools anywhere and whenever they want by adopting portable innovation. Cheng (2015) looked into the elements that influence mobile learning acceptability, namely the role of technological features and compatibility. Nikou and Economides, (2017) agreed with the findings in terms of acceptance and intention to use mobile learning. Although there have been a significant amount of research into mobile learning acceptance, there has been limited research into the driving factors that influence students’ intention to use mobile devices for assessment purposes. It also gave participants greater knowledge of how to create mobile-based evaluations that help learners, improve their learning experience, and promote learning. It is assumed that the adoption of behavioral intention toward mobile learning is a practical idea in the current study that can provide a clear explanation based on extensive literature and theories.

Perceived entertainment

“The ability to meet an audience’s need for escapism, diversion, esthetic satisfaction, or emotional enjoyment,” (Ducoffe, 1996). Customers’ loyalty and value can be increased through entertainment because when the media is viewed as enjoyable, a favorable attitude develops, which leads to positive behavioral intentions. Blumler and Katz (1974) divided 35 media needs articulations into five categories: cognitive needs, which reinforce data, information, and comprehension; affective needs, which strengthen stylish, pleasurable, and passionate experience; individual integrative needs, which reinforce believability, certainty, dependability, and status and join subjective and emotional; social integrative needs, which reinforce contact with family, companions, and the world; and tension needs, which reinforce contact with family, companions, and the world (Zolkepli & Kamarulzaman, 2011). The importance of entertainment in virtual communities on attitudes toward learning is stressed. A cheerful attitude is positively connected with a high entertainment factor in certain media (Haq, 2009). Chen et al., (2012) argue by stating that mobile devices have evolved into indispensable gadgets that are used for leisure as well as productivity enhancement through mobile apps (Islam, Kang, & Yang, 2013). Marketers have adopted this technology to provide information due to the rapid increase in mobile phone usage (Aslam, Batool, & Haq, 2016). Customers can access remote systems to peruse information whenever and wherever wanted. The evolution of communication has a significant impact on the opportunity to grow and learn. Games and other activities are included in learning and teaching methodologies to make education more enjoyable. This type of activity is used to entertain scholars in a variety of educational institutions. The relevance of leisure was further highlighted by Lu et al., (2016) as it is crucial for everyone, especially students, who are under a lot of pressure when studying and leisure time can help them relax. Consumers appear to be more engaged with digital media than with traditional media, even though digital media is more complex. Consumer attitudes and source reliability were both affected directly and significantly by entertainment (Gvili & Levy, 2016). Therefore, based on the literature following hypotheses have been developed:

H1

Entertainment has a positive and significant effect on attitude toward mobile learning.

H6

Entertainment has a positive and significant effect on behavioral intentions toward mobile learning.

Perceived informativeness

“The ability to advise consumers about product options so that purchases generate the best possible satisfaction” (Ducoffe, 1996). Informativeness is a perceptual construct that is typically tested using self-reported items and it contains logical appeal due to its potential to assist a consumer in making an informed decision about message recognition, and therefore it is conceptually distinct from “emotional appeal.” Customers on the internet usually demand subjective qualities in the educational content they expect from websites, such as accuracy, opportunities, and value, and those who can meet these requirements will enjoy favorable reception from their audiences (Lim & Ting, 2012; Richard & Habibi, 2016). According to Dehghani et al., (2016), informativeness is one of the key variables in defining customer value and loyalty which leads to positive behavioral intentions. Both informativeness and entertainment can influence customer behavior. It interacts with users and has an immense impact on purchase intention. In digital communication, informativeness is perceived as an important factor that has a gigantic impact on consumer attitudes (Gvili & Levy, 2016). According to the findings, the most important criteria impacting the intention to re-use mobile advertising were informativeness and credibility (Lin Hsu & Lin 2017; Arli, 2017). Upon the extensive literature following hypotheses have been constructed:

H2

Informativeness has a positive and significant effect on attitude toward mobile learning.

H7

Informativeness has a positive and significant effect on behavioral intentions toward mobile learning.

Perceived irritation

“The approaches that annoy, offend, insult, or are too manipulative, consumers are likely to see it as an unwanted and irritating impact” (Ducoffe, 1996). Irritation is similar to reactance to anything in that customers typically reject advertisements that they consider intrusive. Irritation is a feeling that is influenced by a variety of elements, such as ad frequency, ad content, and ad timing. It is a factor that determines mobile advertising adoption (Zedan & Salem, 2016). Furthermore, the increasing growth in mobile phone usage has led marketers to adopt this medium to provide information, which is a source of frustration (Aslam et al., 2016). Boateng et al., (2016) mandated that the negative consequences of irritation on attitudes toward mobile advertising can be reduced by personal innovativeness, which has a favorable effect on consumers’ attitudes toward mobile advertising. It has been identified as a key determinant of brand loyalty and value by several authors in the past. It has a severe detrimental influence on brand loyalty (Dehghani et al., 2016). Irritation is defined by Gvili and Levy (2016) as digital message avoidance, which is interpreted as message skepticism. The level of discomfort is determined by a variety of circumstances beyond the advertisers’ control. It depends on the attitude of the customers and the type of work he or she does. Consequently, based on the literature, the following hypotheses have been developed:

H3

Irritation has a negative and significant effect on attitude toward mobile learning.

H8

Irritation has a negative and significant effect on behavioral intentions toward mobile learning.

Perceived trust

Trust has received a lot of attention; its definition varies depending on the area, such as psychology, sociology, economics, and marketing. Each profession has its definitions and perspectives on what it means to be trustworthy. It has been around since human civilization and social interaction began. As a result, it serves humanity as both a benefit and a necessity. Morgan and Hunt (1994) defined trust as “existent when one party has faith in the reliability and integrity of a partner.” Trust is a critical construct catalyst in many transactional connections. In the context of a relationship characterized by uncertainty and vulnerability, trust is seen as a controlling mechanism. Additionally, customer sentiments have a significant impact on consumer behavior. Customers, in reality, develop positive feelings toward people with whom they have previously met. Behavioral intention determines planned to conduct, and behavioral intention is influenced by attitudes. In the same way, attitude acts as a link between beliefs and intentions. The topic of mobile trust has recently gotten a lot of attention from researchers. Vance et al., (2008) looked at the impact of mobile trust on users, including system quality, visual appeal, and navigational structure. The importance of perceived trust and privacy was explored using a technological acceptance model, and the report looked into variables influenced by perceived trust. As a result, there are concerns about the transaction’s security and privacy. As a result, clients are more likely to be exposed to danger and mistrust (Chen & Chang, 2013). Perceived trust can lower transaction costs that are not monetary and this cost considers factors, such as time and effort (Gao et al., 2015). According to Lee et al., (2015a, 2015b), privacy and security concerns increase the likelihood of perceived threats and uncertainty. Facilitation is required, as is its continuing use, to reduce perceived risk and build trust. The importance of trust on buy intent was further explained by Bonson Ponte et al., (2015), who discovered that trust has a considerable and favorable impact on behavioral intention. Positive trust emerges when a customer is satisfied, which leads to positive behavioral intentions. Additionally, trust is necessary for the formation of successful collaborations (Suki & Suki, 2017; Wang et al., 2015). People who talk about their trust in humanity imply that they care about other people in society and that those who have deep religion are more tolerant of others. Humans can choose whether or not to be trusting; as a result, trust has a major impact on behavioral intention (Chiu et al., 2017). Thus, based on the said discussion, the following hypotheses have been established:

H4

Perceived trust has a positive and significant effect on attitude toward mobile learning.

H9

Perceived trust has a positive and significant effect on behavioral intentions toward mobile learning.

Perceived value

ZEITHAML (1988) described perceived value as “the consumer’s subjective opinion of the trade-off between benefits acquired from a product or service and sacrifices made for it.” Perceived value is a complex and multi-dimensional concept. It has been identified as one of the most dependable constructs for predicting purchase behavior by researchers (Pura, 2005). Moreover, perceived value is considered and treated as one of the multi-dimensional constructs in the context of consumer value. In previous studies, the validity of four sub-values of customer perceived value was established (Walsh et al., 2014). Hsu and Lin, (2015) explored in greater depth the purchasing purpose of mobile apps. The number of subscribers using smartphones, as well as the use of mobile applications, is growing. The perceived value of an individual influence their attitudes and behavioral intentions significantly. Perceived value has a significant impact on behavioral intention, which is also used to predict repurchase intention (Suki & Suki, 2017). Hernandez-Ortega et al (2017) further discussed the importance of perceived value in post-acceptance behavior for mobile messaging services. Thus, the aforementioned discussion hypothesized perceived value as follows:

H5

Perceived value has a positive and significant effect on attitude toward mobile learning.

H10

Perceived value has a positive and significant effect on behavioral intentions toward mobile learning.

Attitude toward mobile learning

Various predictive and outcome variables, such as entertainment, relaxation, escape time, value, and quality, as well as dependent variables, such as behavioral intention, purchase intention, and buying intention, have been discovered in the literature to operate as mediating variables (Curras-Perez et al., 2014; Mohammadi, 2015a; Zhu & Chang, 2014). In today’s world, technology advances at a breakneck pace, and educational institutions must keep up. Students, teachers, and parents’ attitudes toward mobile learning are researched to achieve mobile-supported education in schools (Huseyin Uzunboylu & Tugun, 2016). Moreover, the study found that attitude is an important factor that influences learning intention. Technology is enabling a wide range of helpful learning opportunities for scholars. Different educational institutions are required to focus on such opportunities to aid people (Park et al., 2012). The rise of mobile devices in recent years has ushered in a new era in education known as mobile learning. Mobile learning, in general, refers to any sort of learning that is facilitated by a mobile device. In recent years, Donaldson (2012), Gan and Balakrishnan (2016), Montrieux et al., (2015), and Park et al., (2012) have all argued for the use of mobile learning. Understanding the factors that influence mobile learning adoption is crucial for success in higher education. It has been revealed that one’s mindset has a significant impact on one’s intention to use mobile learning in future (Yeap et al., 2016). The study employs BITML to investigate the mediating effects of ATML in the link between entertainment, informativeness, irritation, perceived trust, and perceived value, based on evidence that attitude mediates. Thus, the following mediating hypotheses have been developed:

H11

ATML mediates the relationship between entertainment and BITML.

H12

ATML mediates the relationship between informativeness and BITML.

H13

ATML mediates the relationship between perceived irritation and BITML.

H14

ATML mediates the relationship between perceived trust and BITML.

H15

ATML mediates the relationship between perceived value and BITML.

Social influence

According to Ajzen, (1991) “subjective standards are operationalized in a very generic way in terms of experiencing influence with other individuals whose opinions are significant as a source of expectations.” Societal influences and personality traits, such as individual inventiveness, are potentially essential elements for adoption, according to behavioral sciences and individual psychology, and they may be a more relevant aspect in potential adopters’ decisions. The role of social influence in technology acceptance decisions is complex and influenced by a variety of factors. Social influence has been found in several types of research to have a positive impact on behavioral intentions (Chong, 2013; Chong et al., 2012; Leong et al., 2013). M-commerce clients are inspired by their friends to establish behavioral intentions. The link between social influence and behavioral intention has been studied extensively (Jung et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2012), because social groups offer a product’s acceptability. Mobile phone users are often in socially oriented situations and their decisions are influenced by what others think about mobile phones. The desire to rely on others is the fundamental motivator for using social networking services. In recent years, the expansion of media has had a significant impact on decision-making. (Jung et al., 2016). Furthermore, according to Donaldson (2012) and Iqbal and Qureshi (2012), social influence (e.g., instructors, parents, and friends) is expected to have a significant impact on younger students’ willingness to accept the use of mobile devices for educational purposes in the context of mobile learning. During the early phases of mobile learning, it is claimed that social influence has a substantial impact on behavioral intention. Additionally, the inclusion of age and gender tempers social influence, with the results indicating that it has the largest impact on women. Sung et al., (2015) and Reychav et al., (2016) investigated the impact of social influence on mobile learning and mobile device behavioral intention and found that social influence has a positive and significant impact on BITML and that mobile devices are the most promising learning devices. This discussion, on the other hand, broadens the scope of social influence as a moderator in the relationship between attitude and behavior intention because social influence plays such a crucial role in developing the attitude and behavioral intention. Thus, it is hypothesized that.

H17

Social influence moderates the relationship between attitude toward mobile learning (ATML) and behavioral intentions toward mobile learning (BITML) in such a way that the relationship is strengthened when social influence is high.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework is developed based on an extensive literature review (see Fig. 1). The study achieves both theoretical and methodological gaps. Previously various theories and models have been used to measure behavioral intention (Chen & Wells, 1999; Eighmey & McCord, 1998; Fenech, 1998; Korgaonkar & Wolin, 1999; Lim & Ting, 2012). These variables have been drawn from the U&G theory. Henceforth, the present study extends the previous body of literature by investigating factors related to behavioral intention toward mobile learning from a motivational perspective in technology usage by applying U&G theory. The theory is previously used to explore the media, including the web (LaRose & Eastin, 2004; LaRose et al., 2001), blogging (Chua et al., 2012; Hollenbaugh, 2010), and social networking sites such as Twitter (Chen, 2011; Johnson & Yang, 2009), online games (Wu et al., 2010), Facebook (Joinson, 2008), and my space (Raacke & Bonds-Raacke, 2008). As per, the study is related to learning via mobile, so mobile is media and U&G is a suitable theory to study the model (Ha et al., 2015; Ku et al., 2013). The usage of mobile devices for learning purposes is increasing, thus, it is required to study the factors that could play an important role in mobile learning adoption (Viberg & Gronlund, 2013), especially in the framework of developing countries.

This theory has not specifically applied to this context. The suggestions by Mohammadi (2015b) are incorporated to unveil the impact of U&G theory in the mobile learning context as previously the TAM and IS model was incorporated (Hameed & Qayyum, 2018). BITML is the untouched part as mandated by Chen (2011); Cheok and Wong, (2015); Reychav and Wu (2015); Reychav et al., (2016); and Wong et al., (2015). It supports that U&G theory is appropriate in mobile learning context and paves the way for more research of this kind. For better predictive explanation, the study added perceived trust and perceived value as suggested by Wong et al., (2015) to measure the behavioral intention of individuals. Actual usage behavior is not incorporated in the present study because the user acceptance of mobile learning is uncertain, as the concept is novel in Pakistan. Prepositions developed by Bagozzi (2007), Cheng (2015), Lee et al. (2015a, 2015b), Suki and Suki (2017; and Prieto et al. (2015) have been followed by adopting behavioral intention as the suitable construct or dependent variable to determine the BITML. Moreover, the study introduced social influence as a moderator (Wong et al., 2015) to examine the impact on behavioral intentions toward mobile learning. It is considered one of the major constructs to study the behavioral intention of individuals because it has a strong impact on attitude and intention relationships (Papacharissi, & Rubin, 2000; Sung et al., 2015). From the methodological perspective, previous studies examine students’ behavioral intention precisely in first-degree programs; however, in this study students from various departments belonging to different semesters and universities are incorporated so that based on diverse populations generalizability could be increased.

Methodology

The study adopted a positivist philosophy with a deductive approach. It follows a correlational research design along with a descriptive research type. Cross-sectional data were gathered via survey technique (Uma Sekaran, 2005).

Instrument

A total of thirty-eight items of eight constructs were used in the study for the collection of data, along with five items related to demographics (see details of instrument in Annexure A). Five items scales of each construct, i.e., entertainment, informativeness, and irritation were adopted from Ducoffe (1996). The scale of perceived value comprising four items was adapted from Sirdeshmukh et al., (2002). Four items of perceived trust were adapted from Doney and Cannon (1997). The scale of six items of social influence was used developed by Thompson et al., (1991). The scales consisting of four items of attitude and five items of behavioral intention were adapted from Taylor and Todd (1995b). A 7-point Likert scale was used to collect data ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree. It is assumed that a 7-point scale is more reliable, user-friendly, and a better representation of a respondent’s actual assessment. Furthermore, it is an ideal option for surveys as it gives the respondents two moderate opinions, two extreme opinions, two intermediate opinions, and one neutral opinion (Cheng, 2015; Mohammadi, 2015a).

Participants and data collection procedure

The study employed a multistage cluster sampling technique due to its connection with survey research. In the first stage, a basic random sampling strategy was used to make clusters (universities) from Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Lahore, Karachi, and Peshawar. The total number of universities located in these five cities is 150. The students were chosen from each cluster in the second stage using the convenience sampling technique, ensuring that the sample was as diverse as possible. The data was collected from all those students who were experiencing mobile learning due to the Covid-19 breakthrough. They had a better understanding of mobile technologies and were the largest group of users of new technologies. The study’s population was estimated to be around 42,300 students. The sample size calculation was based on the expected response rate and came out as 1056 invites with an estimated response rate of 30%. Thus, 1156 questionnaires were circulated to get the responses. So, the total sample size used for analysis was 586 after removing outliers and missing information.

Data analysis

The demographic analysis shows the majority of the respondents are male and in the age category of 15 to 25 years with bachelors in the context of education. Approximately all respondents have smartphones and experience of using smartphones of 4 to 6 years can be seen in Table 1.

Common method bias

The common method bias (CMB) was calculated using Harman’s single factor test, which measures the variance that can be attributed to a single factor. All thirty-eight items from the eight constructs were loaded into a factor analysis to determine whether a single factor emerges and accounts for the majority of the covariance among the measures. If no single factor emerges and accounts for the majority of the covariance, then it means that common method variance is not a prevalent issue in the study. The variance percentage after extraction is 25.155, which is less than 50%, (see Table 2) indicating that there is no CMB in the study (Tehseen et al., 2017).

The values of the mean and standard deviation of the variables are within the acceptable range. Skewness and kurtosis values are also within the limits, thus showing the normality of the data as can be seen in Table 3. Furthermore, the Pearson correlation of the variables is shown in Table 3 which describes inter-correlation among the variables. All variables have a positive and significant impact on each other except irritation which has a negative and significant correlation with all variables of interest.

Confirmatory factor analysis

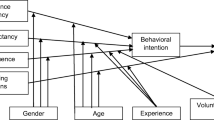

For data analysis, SPSS-25 and AMOS-23 have been used. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS-23; whereas multiple regression, mediation, and moderation have been measured via Process Macros of Hayes & Preacher (2014) using SPSS. The primary reason of conducting CFA using AMOS was to determine how well the construct indicators capture variables. The fit indices indicate how well the model fits with the data (see Fig. 2). It explains whether the variables are independent of each other or co-vary based upon maximum likelihood estimation. Moreover, it has the ability to handle non-parametric data. The goodness of fit statistics shows CMIN/ DF is 2.31, GFI 0.89, AGFI 0.86, RMSEA 0.4, CFI 0.88, and NFI 0.90, therefore the data are a good fit with the model as all values lie in an acceptable range. The factor loadings are loaded appropriately with each item and all items with a value less than 0.4 are removed.

The face validity of the instrument has been measured in three stages with the help of students, then educational specialists, and then students again. Construct validity is assessed via convergent and discriminant validity. CR and AVE values are assessed for convergent validity and can be seen in Table 4, all values of CR are greater than 0.7, and AVE values are greater than 0.5 as the value of all latent constructs is above the minimum threshold value of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2010), thus all values are in an acceptable range. Therefore, the study exhibits convergent validity (Hulland, 1999). The result also ensured the discriminant validity of the model by following Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criteria. It is determined that a set of items measuring specifically their construct are not cross-loading on other constructs. Table 3 shows that the square root of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values of ENT, INF, IRR, PERT, PERV, SI, ATML, and BITML are larger than the corresponding latent variables correlations. The establishment of discriminant validity is also confirmed by the values of HTMT (see Table 5). The HTMT method is a better approach to predict the discriminant validity between the constructs as it measures between trait correlations and within trait correlation of two constructs. All the values are below the threshold of 0.90 (Roemer et al., 2021). Therefore, it is concluded that discriminant validity has been established and the latent factors represent distinct constructs.

Hypotheses testing

Linear relationships among variables were measured via multiple regression analysis. Hypotheses 1, 2, 4, and 5 state ENT, INF, PERT, and PERV has a significant and positive relationship with attitude, whereas H3 states irritation has a negative relationship with attitude. When ENT is increased by one unit, ATML increases by 0.19 units, as seen in Table 6. ATML will increase by 0.12 units if INF is increased by one unit. ATML will drop by − 0.10 units if IRR is increased by one unit. ATML will increase by 0.10 units if PERT is increased by one unit. ATML will increase by 0.36 units if PERV is increased by one unit. Table 6 demonstrates that ENT, INF, IRR, PERT, and PERV all exhibit significant positive beta values, indicating that students with higher scores are more likely to have greater ATML. With a beta value of 0.36, PERV has the greatest influence on ATML. Hence Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are accepted.

Hypotheses 6, 7, 9, 10 state ENT, INF, PERT, and PERV have a significant and positive relationship with BITML, whereas H8 states that IRR has a negative relationship. Table 7 shows that a one-unit increase in ENT results in a 0.20-unit increase in BITML. If INF is increased by one unit, BITML will increase by 0.08. BITML will drop by -0.10 units if IRR is increased by one unit. BITML will increase by 0.14 units if PERT is increased by one unit. BITML will increase by 0.33 units if PERV is increased by one unit. Table 7 demonstrates that ENT, PERT, and PERV have significant positive beta values, indicating that students with higher scores are more likely to have higher BITML scores; however, IRR has a negative significant influence. With a beta value of 0.33, the PERV in the model has a bigger effect on BITML. Therefore, H6 and 8, 9, and 10 are significant, whereas H7 is rejected because INF has an insignificant β value, the insignificant effect suggests that changes in BITML are not associated with a change in INF (see Fig. 3).

Hypothesis 16 states that ATML has a positive and significant effect on BITML. If ATML is raised by 1 unit, the BITML will be increased by 0.70 units as can be seen in Table 8, thus accepting H16.

Mediation and moderation analysis

The study used Macro Process by Hayes & Preacher (2014). Model 4 with bootstrapping to boost the statistical power of mediation analysis (Inman & Nikolova, 2017). The current study uses 5000 samples to repeat the bootstrapping technique. If the indirect effect estimates’ 95 percent confidence interval does not include zero, the mediator is considered significant.

To determine the mediating effect of ATML between ENT and BITML, a path analysis was performed. Table 9 shows that the total impact (0.42, p < 0.05) and indirect effect (0.27, p < 0.05) are both significant (based on 5000-bootstrapped samples). ATML mediates the link between ENT and BITML, according to the data (lower 95 percent CI = 0.2065 and higher 95 percent CI = 0.3401). Because the direct effect (0.14, p < 0.05) is also strong, partial mediation is present. To determine the mediating effect of ATML between INF and BITML, a path analysis was performed. Table 9 shows that the total effect (0.47, p < 0.05) and indirect impact (0.33, p < 0.05) are both significant (based on 5000-bootstrapped samples). ATML mediates the association between INF and BITML, according to the findings (lower 95 percent CI = 0.2645 and higher 95 percent CI = 0.4212). Because the direct effect (0.14, p < 0.05) is also strong, partial mediation is present. To determine the mediating effect of ATML between IRR and BITML, a path analysis was performed. Table 9 shows that the total effect (− 0.18, p < 0.05) and indirect effect (− 0.13, p < 0.05) are both significant (based on 5000-bootstrapped samples). ATML mediates the link between IRR and BITML, according to the data (lower 95 percent CI = -0.1974 and higher 95 percent CI = − 0.0783). The direct effect (0.14, p < 0.05) is likewise substantial, indicating that there is full mediation. To determine the mediating effect of ATML between PERT and BITML, a path analysis was performed. Table 9 shows that the total effect (0.58, p < 0.05) and indirect impact (0.36, p < 0.05) are both significant (based on 5000-bootstrapped samples). ATML mediates the link between PERT and BITML, according to the findings (lower 95 percent CI = 0.2865 and higher 95 percent CI = 0.4510). Because the direct effect (0.21, p < 0.05) is also strong, partial mediation is present. To determine the mediating effect of ATML between PERV and BITML, a path analysis was performed. Table 9 shows that the total effect (0.77, p < 0.05) and indirect impact (0.46, p < 0.05) are both significant (based on 5000-bootstrapped samples). ATML mediates the link between PERV and BITML, according to the findings (lower 95 percent CI = 0.3763 and higher 95 percent CI = 0.5647) because the direct effect (0.31, p < 0.05) is also strong, partial mediation is present.

Hypothesis 17 states that SI strengthens the association between ATML and BITML. To test Hayes & Preacher (2014) (Model 1)’s moderation study of SI between ATML and BITML via Process Macro, a route analysis was performed. First, the significance of the moderation effect is determined; if it is significant, then moderation exists and is meaningful, as evidenced by the values of the lower and upper limit confidence intervals. When zero does not fall between the two extremes, moderation is significant. The fact that the lower limit is − 0.024 and the higher limit is − 0.0013 indicates that zero does not lie between the two values, indicating that moderation exists. Table 10 demonstrates the low, medium, and high effect of SI in the relationship between ATML and BITML to determine which condition has a significant effect. SI dampens the impact on the link between ATML and BITML, as seen in Fig. 4.

Discussion

The study objective was to determine the factors related to behavioral intention toward mobile learning. Mobile devices have evolved into vital gadgets that are used as a source of pleasure, with their productivity boosted by a variety of mobile apps. Mobile apps play an important part in mobile commerce uptake and students find them entertaining. Students’ attitudes are influenced by the rapid growth of mobile applications, video games, and mobile commerce. The hypothesis postulated that entertainment significantly influences ATML and BITML is supported in the study. Students use technology to reduce stress and boost their leisure time while studying. It influences not only one’s attitude but also one’s behavior (Tuparov et al., 2015). The findings of research conducted by Arli (2017) and Lin et al., (2017) found that the spread of mobile devices and the internet have boosted students’ capacity to be informed and supported the current findings of the study. In contrast to the literature, informativeness does not affect BITML. The study’s findings differ from those reported in the literature by Shim and Youn (2013) and Zedan and Salem (2016) on the direct association between informativeness and behavioral intention. The purpose of this research is to perceive if there is a direct relationship between informativeness and BITML. As a result, it is deemed inconsequential in the context of this study, indicating that it does not affect students’ behavioral intentions. This suggests that informativeness does not encourage students to behave positively. This could be because the mobile learning concept is emerging in Pakistan, and many individuals, even educational institutions, are unfamiliar with it.

The findings of this study support Zedan and Salem’s (2016) hypothesis that irritation is similar to reactance and that individuals generally respond badly when they are uncomfortable and considered intrusive. With the advancement of technology, the component of aggravation and irritation has increased, which can have a detrimental impact on people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions (Hasan, 2016). Furthermore, studies performed by Ponte et al., (2015) and Lee et al., (2015a, 2015b) discovered that trust is critical for building connections, whereas security and privacy issues raise risk and ambiguity. Trust was identified as a key determinant of attitude, and it was discovered that trust has a favorable and significant impact on attitudes toward mobile learning. As a result, as recommended by Suki and Suki (2017) and Wang et al., (2015), it is critical to establish positive consumer trust. People have a favorable attitude and behavioral intention when they view mobile learning to be of great value. As a result, developing positive student attitudes is a crucial endeavor (Naciri et al., 2020; Shin & Kang, 2015).

The study postulated that ATML mediates the relationships between entertainment, informativeness, irritation, perceived trust, and perceived value with BITML. In today’s world, technology is evolving at a breakneck pace, forcing educational institutions to adopt cutting-edge technology, particularly in the field of education. The findings of the study showed that attitude has been found to mediate relationships between predictors, such as entertainment, informativeness, irritation, value, and trust, with behavioral intention (Curras-Perez et al., 2014; Mohammadi, 2015a; Zhu & Chang, 2014). In general, mobile learning may be defined as any type of learning that occurs through the use of a mobile device, and it has gotten a lot of attention in recent years (Donaldson, 2012; Montrieux et al., 2015; Park et al., 2012). For mobile learning to succeed in higher education, it is critical to understand the elements that drive its adoption. Attitude has been shown to have a major impact on students’ behavioral intentions toward learning (Yeap et al., 2016; Criollo-C, 2021).

Social influence moderates the relationship between ATML and BITML. According to Chong et al., (2012), Chong (2013), and Leong et al., (2013) social influence has a favorable effect on students’ behavioral intentions because social groups provide substantial evidence regarding the appropriateness of a certain product, social impact minimizes the risk of adoption. This aids students in their decision-making process (Alzaidi & Shehawy, 2022). As a result, the evidence strongly suggests that social influence is a determinant of attitude and behavioral intention and it moderates the connection. However, it moderates the relationship in the current investigation, but negatively. This is due to the differences in culture and industry because mobile learning is a relatively new phenomenon in Pakistan, and people lack sufficient information and evidence to support it. Since social groupings have a negative reaction to it thus people do not consider mobile learning to be an appropriate learning tool. Another argument could be that because mobile users are young and have the requisite abilities to operate mobile technology, they do not require the influence of a social group to navigate in the context of mobile learning. The study is comparable to Tan et al., (2014) that social factors did not affect the behavioral intention to adopt mobile learning. As a result, it is concluded that social impact moderates negatively rather than strengthening the association between ATML and BITML in students.

Theoretical implications

In social and psychological situations, behavioral intention is a common manifestation but in the context of mobile learning, it is at the embryonic level. The theoretical implication of the study is three-fold: firstly, the study developed and measured a comprehensive theoretical framework based on literature to measure BITML. Secondly, the mediating effect of ATML is explored between perceived entertainment, informativeness, irritation, trust, and value with BITML. Taken together these findings suggest that developing a favorable attitude among learners positively affects BITML. Lastly, the study measured the moderating effect of social influence in the relationship between ATML and BITML.

Practical implications

The study exhibits various practical implications: firstly, it will assist educational institutes that how BITML has emerged and how it is shaping the attitude of learners. They must accurately depict the concept of mobile learning and devise tactics to encourage learners to embrace mobile learning by demonstrating that it not only entertains but also gives comprehensive information. Educational institutions should provide user-friendly apps with improved reading layouts so that students may learn on the go. Secondly, the study is imperative for service providers because internet services are the prerequisites for mobile learning. The internet should be made more accessible to make it easier to get learning materials. Thirdly, the study is vital for the telecom industry as mobile learning is associated with technology, thus they need to make the devices compatible with learning features and simple to operate for the general public. They should build screens that are large and faultless, allowing for a clear display.

Limitations and future research

The study might have numerous limitations and based upon limitations future directions are provided. Firstly, the study has incorporated various factors to measure behavioral intention but in future studies, one may add personality traits of individuals who are supposed to practice mobile learning along with various other variables to depict the BITML. Secondly, the study is majorly based on U&G theory and TPB, thus the conceptual model needs to be tested in comparison to TAM and UTAUT models. Thirdly, the study is based upon cross-sectional data that hinder generalizability thus in future, time lag data can be used to measure the behavior of individuals. Lastly, in the context of analysis techniques, the latest software might be used for more generalizability.

Conclusion

In general, the study started with the design of the research model, which was accomplished by the analysis of relevant literature and the formulation of research hypotheses that may provide answers to the research questions. The study investigated the effect of perceived entertainment, informativeness, irritation, trust, and value on ATML and BITML. Moreover, the study determined the mediating role of attitude in the aforementioned relationships and moderating role of social influence in the relationship between ATML and BITML. The findings showed that perceived entertainment, perceived informativeness, perceived trust, and perceived value have direct and significant effects on attitude toward mobile learning, whereas perceived irritation has a negative effect. For the direct effect on BITML, all variables showed significant impact except informativeness. Furthermore, the study confirmed the role of ATML as a mediator and social influence as a moderator. Consequently, significant advances have been facilitated by modern technology and globalization, and mobile learning has expanded the scope of electronic and distance education, particularly with the pandemic Covid-19 worldwide. The shift to mobile learning will be successful, and it will be useful for a long time.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Al-Bashayreh, M., Almajali, D., Altamimi, A., Masa’deh, R. E., & Al-Okaily, M. (2022). An empirical investigation of reasons influencing student acceptance and rejection of mobile learning apps usage. Sustainability, 14(7), 4325.

Alturki, U., & Aldraiweesh, A. (2022). Students’ perceptions of the actual use of mobile learning during COVID-19 pandemic in higher education. Sustainability, 14(3), 1125.

Alzaidi, M. S., & Shehawy, Y. M. (2022). Cross-national differences in mobile learning adoption during COVID-19. Education Training. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031125

Arli, D. (2017). Does social media matter? Investigating the effect of social media features on consumer attitudes. Journal of Promotion Management, 23(4), 521–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2017.1297974

Aslam, W., Batool, M., & Ul Haq, Z. (2016). Attitudes and behaviors of the mobile phone users towards SMS advertising: A study in an emerging economy. Journal of Management Sciences, 3(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.20547/jms.2014.1603105

Bagozzi, R. P. (2007). The legacy of the technology acceptance model and a proposal for a paradigm shift. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 8(7), 244–254.

Blumler, J. G., & Katz, E. (1974). The uses of mass communications: current perspectives on gratifications research. Sage Annual Reviews of Communication Research Volume III. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Boateng, H., Okoe, A. F., & Omane, A. B. (2016). Does personal innovativeness moderate the effect of irritation on consumers’ attitudes towards mobile advertising? Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 17(3), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2015.53

Bonsón Ponte, E., Carvajal-Trujillo, E., & Escobar-Rodríguez, T. (2015). Influence of trust and perceived value on the intention to purchase travel online: Integrating the effects of assurance on trust antecedents. Tourism Management, 47, 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.009

Chen, G. M. (2011). Tweet this: A uses and gratifications perspective on how active Twitter use gratifies a need to connect with others. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 755–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.10.023

Chen, H. J., Yan Huang, S., Chiu, A. A., & Pai, F. C. (2012). Industrial management & data systems. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 112(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0266

Chen, Q., & Wells, W. D. (1999). Attitude toward the Site. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(5), 27–37.

Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2013). Greenwash and Green Trust: The Mediation Effects of Green Consumer Confusion and Green Perceived Risk. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(3), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

Cheng, Y. M. (2015). Towards an understanding of the factors affecting m-learning acceptance: Roles of technological characteristics and compatibility. Asia Pacific Management Review, 20(3), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2014.12.011

Cheok, M. L., & Wong, S. L. (2015). Predictors of e-learning satisfaction in teaching and learning for school teachers: A literature review. International Journal of Instruction, 8(1), 75–90.

Chiu, J. L., Bool, N. C., & Chiu, C. L. (2017). Challenges and factors influencing initial trust and behavioral intention to use mobile banking services in the Philippines. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(2), 246–278. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-08-2017-029

Chong, A. Y. L. (2013). Predicting m-commerce adoption determinants: A neural network approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 40(2), 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.07.068

Chong, A. Y. L., Chan, F. T. S., & Ooi, K. B. (2012). Predicting consumer decisions to adopt mobile commerce: Cross country empirical examination between China and Malaysia. Decision Support Systems, 53(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2011.12.001

Chua, A. Y. K., Goh, D. H. L., & Lee, C. S. (2012). Mobile content contribution and retrieval: An exploratory study using the uses and gratifications paradigm. Information Processing and Management, 48(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2011.04.002

Contractor, N. S., & DeChurch, L. A. (2014). Integrating social networks and human social motives to achieve social influence at scale. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(Suppl), 13650–13657. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1401211111

Criollo-C, S., Guerrero-Arias, A., Jaramillo-Alcázar, Á., & Luján-Mora, S. (2021). Mobile learning technologies for education: Benefits and pending issues. Applied Sciences, 11(9), 4111.

Curras-Perez, R., Ruiz-Mafe, C., & Sanz-Blas, S. (2014). Determinants of user behavior and recommendation in social networks: An integrative approach from the users and gratifications perspective. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 114(9), 1477–1498. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2014-0219

Dehghani, M., Niaki, M. K., Ramezani, I., & Sali, R. (2016). Evaluating the influence of YouTube advertising for attraction of young customers. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.037

Donaldson, R. L. (2012). Student acceptance of mobile learning. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section b: THe Sciences and Engineering, 73, 168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.483

Doney, M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). Trust examination of the nature of in buyer-seller relationship for assistance. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251829

Ducoffe, R. H. (1996). Advertising value and advertising on the web. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(5), 21–35.

Eighmey, J., & McCord, L. (1998). Uses and gratifications of sites on the world wide web. Journal of Business Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00061-1

Fenech, T. (1998). Using perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness to predict acceptance of the World Wide Web. Computer Networks and ISDN Systems, 30(1), 629–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00028-2

Feng, X., Fu, S., & Qin, J. (2016). Determinants of consumers’ attitudes toward mobile advertising: The mediating roles of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.024

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

Gan, C. L., & Balakrishnan, V. (2016). An empirical study of factors affecting mobile wireless technology adoption for promoting interactive lectures in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(1), 214–239.

Gao, L., Waechter, K. A., & Bai, X. (2015). Understanding consumers’ continuance intention towards mobile purchase: A theoretical framework and empirical study—A case of China. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.014

Gvili, Y., & Levy, S. (2016). Antecedents of attitudes toward eWOM communication: Differences across channels. Internet Research, 26(5), 1030–1051. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-08-2014-0201

Ha, Y. W., Kim, J., Libaque-Saenz, C. F., Chang, Y., & Park, M. C. (2015). Use and gratifications of mobile SNSs: Facebook and KakaoTalk in Korea. Telematics and Informatics, 32(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2014.10.006

Hair, J. F., Ortinau, D. J., & Harrison, D. E. (2010). Essentials of marketing research (Vol. 2). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Hameed, F., & Qayyum, A. (2018). Determinants of behavioral intention towards mobile learning in Pakistan: Mediating role of attitude. Business and Economic Review, 10(1), 33–61.

Haq, Z. U. (2009). E-mail advertising: A study of consumer attitude toward e-mail advertising among Indian users. Journal of Retail and Leisure Property, 8(3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1057/rlp.2009.10

Hasan, B. (2016). Perceived irritation in online shopping: The impact of website design characteristics. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.056

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/bmsp.12028

Hernandez-Ortega, B., Aldas-Manzano, J., Ruiz-Mafe, C., & Sanz-Blas, S. (2017). Perceived value of advanced mobile messaging services. A cross-cultural comparison of Greek and Spanish users. Information Technology & People. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-01-2014-0017

Hollenbaugh, E. E. (2010). Personal journal bloggers: Profiles of disclosiveness. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1657–1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.014

Hsu, C. L., & Lin, J. C. C. (2015). What drives purchase intention for paid mobile apps?-An expectation confirmation model with perceived value. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2014.11.003

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204.

Humida, T., Al Mamun, M. H., & Keikhosrokiani, P. (2022). Predicting behavioral intention to use e-learning system: A case-study in Begum Rokeya University, Rangpur Bangladesh. Education and Information Technologies, 27(2), 2241–2265.

Inman, J. J., & Nikolova, H. (2017). Shopper-facing retail technology: A retailer adoption decision framework incorporating shopper attitudes and privacy concerns. Journal of Retailing, 93(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2016.12.006

Iqbal, S., & Qureshi, I. A. (2012). M-learning adoption: A perspective from a developing country. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i3.1152

Islam, M., Kang, M., & Yang, S. B. (2013). A research to identify the relationship between consumers’ attitude and mobile advertising. PACIS 2013 Proceedings, 39. http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2013/39

Johnson, P. R., & Yang, S. U. (2009). Uses and gratifications of Twitter An examination of user motives and satisfaction of Twitter use. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, (September 2009), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Joinson, A. N. (2008). “Looking at”, “looking up” or “keeping up with” people? Motives and uses of Facebook. CHI 2008 Proceedings: Online Social Networks, 1027–1036.

Jung, J., Shim, S. W., Jin, H. S., & Khang, H. (2016). Factors affecting attitudes and behavioral intention towards social networking advertising: A case of Facebook users in South Korea. International Journal of Advertising, 35(2), 248–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1014777

Kim, H. W., Xu, Y., & Gupta, S. (2012). Which is more important in Internet shopping, perceived price or trust? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 11(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2011.06.003

Kolog, E. A., Sutinen, E., Vanhalakka-Ruoho, M., Suhonen, J., & Anohah, E. (2014). Using unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model to predict students behavioral intention to adopt and use ecounseling in Ghana. Modern Education and Computer Science Modern Education and Computer Science, 1(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.5815/ijmecs.2014.01.01

Korgaonkar, P. K., & Wolin, L. D. (1999). A multivariate analysis of web usage. Journal of Advertising Research, 39, 53–68.

Ku, Y. C., Chu, T. H., & Tseng, C. H. (2013). Gratifications for using CMC technologies: A comparison among SNS, IM, and e-mail. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.009

LaRose, R., & Eastin, M. S. (2004). A social cognitive theory of Internet uses and gratifications: Toward a new model of media attendance. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48(3), 358–377. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4803_2

LaRose, R., Mastro, D., & Eastin, M. S. (2001). Understanding internet usage. Social Science Computer Review, 19(4), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443930101900401

Lee, D., Moon, J., Kim, Y. J., & Yi, M. Y. (2015b). Antecedents and consequences of mobile phone usability: Linking simplicity and interactivity to satisfaction, trust, and brand loyalty. Information and Management, 52(3), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.12.001

Lee, S., Park, E., Kwon, S., & del Pobil, A. (2015a). Determinants of behavioral intention to use south korean airline services: Effects of service quality and corporate social responsibility. Sustainability, 7(8), 11345–11359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70811345

Leong, L. Y., Ooi, K. B., Chong, A. Y. L., & Lin, B. (2013). Modeling the stimulators of the behavioral intention to use mobile entertainment: Does gender really matter? Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), 2109–2121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.004

Lim, W. M., & Ting, D. H. (2012). E-shopping: An analysis of the uses and gratifications theory. Modern Applied Science, 6(5), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v6n5p48

Lin, C. W., Hsu, Y. C., & Lin, C. Y. (2017). User perception, intention, and attitude on mobile advertising. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 15(1), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2017.080580

Lu, C. Y., Yeh, W. J., & Chen, B. T. (2016). The study of international students’ behavior intention for leisure participation: Using perceived risk as a moderator. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(2), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2015.1115267

Luo, X., Li, H., Zhang, J., & Shim, J. P. (2010). Examining multi-dimensional trust and multi-faceted risk in initial acceptance of emerging technologies: An empirical study of mobile banking services. Decision Support Systems, 49(2), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2010.02.008

McDonald, R. I., & Crandall, C. S. (2015). Social norms and social influence. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.04.006

Milosevic, I., Zivkovic, D., Manasijevic, D., & Nikolic, D. (2015). The effects of the intended behavior of students in the use of M-learning. Computers in Human Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.041

Mohammadi, H. (2015a). Social and individual antecedents of m-learning adoption in Iran. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 191–207.

Mohammadi, H. (2015b). Factors affecting the e-learning outcomes: An integration of TAM and IS success model. Telematics and Informatics, 32(4), 701–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.03.002

Mohammadi, H. (2015c). Investigating users’ perspectives on e-learning: An integration of TAM and IS success model. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.044

Montrieux, H., Vanderlinde, R., Schellens, T., & De Marez, L. (2015). Teaching and learning with mobile technology: A qualitative explorative study about the introduction of tablet devices in secondary education. PLoS ONE, 10(12), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144008

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). Theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766710391135

Naciri, A., Baba, M. A., Achbani, A., & Kharbach, A. (2020). Mobile learning in higher education unavoidable alternative during COVID-19. Aquademia, 4(1), 20016-ep20022.

Nikou, S. A., & Economides, A. A. (2017). Mobile-based assessment: Investigating the factors that influence behavioral intention to use. Computers & Education, 109, 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.02.005

Papacharissi, Z., & Rubin, A. M. (2000). Predictors of Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44(2), 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4402_2?needAccess=true

Park, S. Y., Nam, M., & Cha, S. (2012). University students’ behavioral intention to use mobile learning: Evaluating the technology acceptance model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(4), 592–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01229.x

Prieto, J. C. S., Migueláñez, S. O., & García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2015). Mobile acceptance among pre-service teachers. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality - TEEM ’15, 131–137. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1145/2808580.2808601

Pura, M. (2005). Linking perceived value and loyalty in location-based mobile services. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 15(6), 509–538. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520510634005

Raacke, J., & Bonds-Raacke, J. (2008). Myspace and facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory to exploring friend-networking sites. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(2), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0056

Reychav, I., Dunaway, M., & Kobayashi, M. (2016). Understanding mobile technology-fit behaviors outside the classroom. Computers and Education, 87, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.005

Reychav, I., & Wu, D. (2015). Are your users actively involved? A cognitive absorption perspective in mobile training. Computers in Human Behavior, 44, 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.021

Reza Jalilvand, M., Samiei, N., Dini, B., & Yaghoubi Manzari, P. (2012). Examining the structural relationships of electronic word of mouth, destination image, tourist attitude toward destination and travel intention: An integrated approach. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 1(1–2), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.001

Richard, M. O., & Habibi, M. R. (2016). Advanced modeling of online consumer behavior: The moderating roles of hedonism and culture. Journal of Business Research, 69(3), 1103–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.026

Roemer, E., Schuberth, F., & Henseler, J. (2021). HTMT2–an improved criterion for assessing discriminant validity in structural equation modeling. Industrial Management & Data Systems. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-02-2021-0082

Sanakulov, N., & Karjaluoto, H. (2015). Consumer adoption of mobile technologies: A literature review. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 13(3), 244. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMC.2015.069120

Shim, K., & Youn, M. (2013). Mediating Effect of Informativeness Joyfulness and Trust In Internet Shopping Mall Image on Consumer Purchase Intention, In KODISA ICBE (International Conference on Business and Economics) 8(September), 205–213

Shin, W. S., & Kang, M. (2015). The use of a mobile learning management system at an online university and its effect on learning satisfaction and achievement. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(3), 110–130. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i3.1984

Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J., & Sabol, B. (2002). Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 15–37.

Sophonhiranrak, S. (2021). Features, barriers, and influencing factors of mobile learning in higher education: A systematic review. Heliyon, 7(4), e06696.

Suki, M. N., & Suki, M. N. (2017). Flight ticket booking app on mobile devices: Examining the determinants of individual intention to use. Journal of Air Transport Management, 62, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.04.003

Sung, H., Jeong, D., Jeong, Y. S., & Shin, J. I. (2015). The relationship among self-efficacy, social influence, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and behavioral intention in mobile learning service. International Journal of u-and e-Service, Science and Technology, 8(9), 197–206.

Tan, G. W. H., Ooi, K. B., Leong, L. Y., & Lin, B. (2014). Predicting the drivers of behavioral intention to use mobile learning: A hybrid SEM-neural networks approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.052

Taylor, S., & Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 144–176.

Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168.

Thompson, R. L., Higgins, C. A., & Howell, J. M. (1991). Personal computing: Toward a conceptual model of utilization. MIS Quarterly, 15(1), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.2307/249443

Tuparov, G., Alsabri, A. A. A., & Tuparova, D. (2015). Student’s readiness for mobile learning in Republic of Yemen - A pilot study. Proceedings of 2015 International Conference on Interactive Mobile Communication Technologies and Learning, IMCL 2015, (November), 190–194. https://doi.org/10.1109/IMCTL.2015.7359584

Uma Sekaran, R. B. (2005). Research methods for business (5th ed.). Wiley.

Uzunboylu, H., & Tugun, V. (2016). Validity and reliability of tablet supported education attitude and usability scale. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 22(1), 82–93.

Vance, A., Elie-Dit-Cosaque, C., & Straub, D. W. (2008). Examining trust in information technology artifacts: The Effects of system quality and culture. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 73–100. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240403

Viberg, O., & Grönlund, Å. (2013). Cross-cultural analysis of users’ attitudes toward the use of mobile devices in second and foreign language learning in higher education: A case from Sweden and China. Computers & Education, 69, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.07.014

Walsh, G., Shiu, E., & Hassan, L. M. (2014). Replicating, validating, and reducing the length of the consumer perceived value scale. Journal of Business Research, 67(3), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.05.012

Wang, S. W., Ngamsiriudom, W., & Hsieh, C. H. (2015). Trust disposition, trust antecedents, trust, and behavioral intention. Service Industries Journal, 35(10), 555–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2015.1047827

Wong, C. H., Tan, G. W. H., Tan, B. I., & Ooi, K. B. (2015). Mobile advertising: The changing landscape of the advertising industry. Telematics and Informatics, 32(4), 720–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.03.003

Wu, J. H., Wang, S. C., & Tsai, H. H. (2010). Falling in love with online games: The uses and gratifications perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1862–1871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.033

Yang, S., Lu, Y., Gupta, S., Cao, Y., & Zhang, R. (2012). Mobile payment services adoption across time: An empirical study of the effects of behavioral beliefs, social influences, and personal traits. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.019

Yeap, J. A. L., Ramayah, T., & Soto-Acosta, P. (2016). Factors propelling the adoption of m-learning among students in higher education. Electronic Markets, 26(4), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0214-x

Zedan, M., & Salem, Y. (2016). Factors affecting consumer attitudes, intentions, and behaviors toward SMS advertising in Palestine. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i4/80216

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251446

Zhu, D. H., & Chang, Y. P. (2014). Investigating consumer attitude and intention toward free trials of technology-based services. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 328–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.09.008

Zolkepli, I. A., & Kamarulzaman, Y. (2011). Understanding social media adoption : The role of perceived media needs and technology characte4ristics. World Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 188–199.

Funding

No third party/funding source is associated with research paper except the authors with no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical considerations

I hereby declare that this research paper is the authors' own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere. The research paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. The paper reflects the authors' own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner. The responsibility of this statement shall be borne by the authors of the paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Annexure

Entertainment

Mobile learning is entertaining to me.

I think that mobile learning is fun to use.

I feel excited while using mobile learning.

I enjoy it when I do mobile learning.

I think that mobile learning is cool.

Informativeness

Mobile learning gives me quick and easy access to large volumes of information.

Information obtained from mobile learning is useful.

I learned a lot from using mobile learning.

The information obtained from mobile learning is helpful.

Mobile learning makes acquiring information inexpensively.

Irritation

I think that mobile learning is irritating.

Mobile learning is annoying to me.

I feel that mobile learning is confusing.

I think that mobile learning is messy.

Mobile learning is deceptive to me.

Perceived trust

The mobile learning systems are trustworthy.

The mobile learning systems have a good reputation as other systems.

The mobile learning systems are competent and effective as other systems.

I do not doubt the reputation of mobile learning systems.

Perceived value

Compared to the fee I need to pay, the use of mobile learning offers value for money.

Compared to the effort I need to put in, the use of mobile learning is beneficial to me.

Compared to the time I need to spend, the use of mobile learning is worthwhile to me.

Overall, the use of mobile learning delivers me good value.

Social influence

People who influence my behavior think, I should use mobile learning.

People who are important to me think I should use mobile learning.

My close friends think I should use mobile learning.

My colleagues think I should use mobile learning.

My peers think I should use mobile learning.

People whose opinion I value prefer that, I should use mobile learning.

ATML

I think that using mobile learning is a good idea.

I think that using mobile learning for learning purposes would be a wise idea.

I think that using mobile learning is a pleasant experience.