Summary

Background

Beta-lactam antibiotics (BLA) are the treatment of choice for a large number of bacterial infections. Putative BLA allergies are often reported by patients, but rarely confirmed. Many patients do not receive BLA due to suspected allergy. There is no systematic approach to risk stratification in the case of a history of suspected BLA allergy.

Methods

Using the available stratification programs and taking current guidelines into account, an algorithm for risk stratification, including recommendations on the use of antibiotics in cases of compellingly indicated BLA despite suspected BLA allergy, was formulated by the authors for their maximum care university hospital.

Results

The hospital is in great need of recommendations on how to deal with BLA allergies. Patient-reported information in the history forms the basis for classifying the reactions into four risk categories: (1) BLA allergy excluded, (2) benign delayed reaction, (3) immediate reaction, and (4) severe cutaneous and extracutaneous drug reaction. Recommendations strictly depend on this classification and range from use of full-dose BLA or use of BLA under certain conditions (e.g., two-stage dose escalation, non-cross-reactive BLA only) to prohibiting all BLA and the use of alternative non-BLA. In case of suspected immediate or delayed allergic reactions, there is an additional recommendation regarding subsequent allergy testing during a symptom-free interval.

Conclusion

Triage of patients with suspected BLA is urgently required. While allergy testing, including provocation testing, represents the most reliable solution, this is not feasible in all patients due to the high prevalence of BLA allergies. The risk stratification algorithm developed for the authors’ hospital represents a tool suitable to making a contribution to rational antibiotic therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Beta-lactam antibiotics (BLA) are not only the drugs of choice for the treatment of numerous bacterial infections, but also the most frequent triggers of drug allergies and fatal drug-related anaphylaxis [1, 2]. Approximately 3–10% of all patients or parents of affected children in the population and up to 19% of all hospitalized patients report a BLA allergy [1, 2]. Since suspected hypersensitivity can be confirmed by allergy testing in only less than 10% [1], failure to take into account allergies reported in the patient history is of no consequence in many cases. Parainfectious exanthems or acute urticaria are frequently misinterpreted as cutaneous drug reactions. The high number of BLA allergies reported in patient histories hampers the selection of a suitable antibiotic. The possible consequences of incorrectly classified BLA allergies in the patient history include the following: increased use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, ineffective treatment of bacterial infections, a high number of sick days and hospitalization days, the induction of bacterial multiresistance and high costs.

Healthcare providers urgently need a systematic approach to risk stratification in the case of suspected BLA allergy in the patient’s history. Of all the strategies to investigate assumed BLA allergies, consultation by an allergologist, including skin testing followed by provocation testing, is the most reliable, but also the most time- and resource-consuming approach. However, in view of the millions of patients affected, additional instruments for systematic evaluations are needed in order to offer low-risk patients faster treatment options. The preferred protocol to investigate true BLA allergy should be simple to perform and yield as few false-positive results as possible [2].

In recent years, algorithms referred to as “de-labeling strategies”, which are proven to reduce antibiotic use and improve treatment outcomes, have been described in the US [12], Australia [10], New Zealand [14], Great Britain [11, 13], and Germany [16]. Algorithms such as these, some of which are computer-assisted, attempt to classify the most likely mechanism of hypersensitivity reaction on the basis of clinical manifestations of BLA allergy in the patient’s history. The further procedure is determined according to the respective classification, ranging from complete avoidance of the substance class in the future to skin testing plus/minus provocation testing to no restrictions whatsoever.

In 2019, this topic was discussed intensively in the German BLA allergy guideline [1], as well as in the EAACI European position paper [4]. Therefore, on the basis of existing stratification programs and taking into account current German and European recommendations, the authors formulated an algorithm, as well as the following recommendations on the use of antibiotics in compelling indications, for their 1161-bed, maximum-care university hospital in order to stratify the risk of BLA allergy in the patient history.

Methods

Between March 2019 and July 2019, members of the Antibiotic Stewardship (ABS) Unit (hospital pharmacy, medical microbiology, intensive medicine), Infectiology and Allergology at the Klinikum rechts der Isar, Munich, drew up an algorithm in an interdisciplinary approach on how to proceed in the case of suspected BLA allergy when the use of a BLA is compellingly indicated (primarily in severe or acute infection). They analyzed the guidelines and position papers that were available or in preparation, as well as the respective literature [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Recommendations were made on the basis of a risk assessment that takes into account possible cross reactions between BLA and classifies these reactions into putative underlying pathomechanisms. The pathomechanisms are suspected on the basis of clinical symptoms reported in the patient history and recorded using a checklist.

Results

Situations in which antibiotic use is compellingly indicated for severe or acute infection in the setting of a concomitant history of BLA allergy arise in almost 10% of patients at the authors’ hospital. These patients need to be triaged with regard to the further approach according to a risk stratification system, either receiving direct administration of alternative non-BLA and a recommendation for later allergy testing during a symptom-free interval, or direct use of BLA under certain conditions (e.g., two-stage dosing) and taking into account possible cross-reactivity.

Clinical symptoms reported in the patient’s history form the basis for the classification into pathomechanisms. The information needs to be rapidly recorded in clinical routine, but must also include all aspects relevant to the BLA allergy.

Relevant data on the suspected BLA allergy is collected using a targeted short patient history that is structured as a three-part checklist (Fig. 1). Examples of possible alternatives are provided, and applicable information can be underlined or ticked. Although this short patient history cannot replace the differentiated allergy history taken by a specialist physician during allergy diagnostics, it is sufficient to provide an acute assessment in the majority of cases.

The first questions on the checklist cover information regarding known allergies and tolerance of other antibiotic substance classes, the timing of the reaction(s), the suspected BLA, the duration of use prior to the onset of the reaction, the time interval between last use and the reaction, duration of symptoms, and allergy testing already performed.

The second part of the checklist relates to symptoms in the patient’s history following the use of BLA (Fig. 1). Typical examples of cutaneous, respiratory, systemic, hematological, neurological, and renal manifestations or symptoms of the immediate reaction and of the delayed reaction are given and categorized by color into levels of severity, i.e., “mild”, “moderate,” and “life-threatening”. Non-allergic reactions, e.g., gastrointestinal reactions such as nausea and vomiting that did not occur in the setting of an anaphylactic reaction, are clearly distinguished from the symptoms of the immediate reaction and the delayed reaction [4, 15]. To enable better clinical differentiation between an immediate reaction involving urticaria or angioedema and maculopapular exanthem, which can also resemble urticaria in the first few days [4], a differentiation aid was developed (Table 1).

The third part lists the measures that had been taken following onset of the reaction with suspected BLA allergy in order to collect further information on the severity. For example, parenteral drug administration, in particular adrenaline, or hospital admission suggest a high severity level.

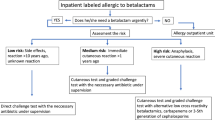

Figure 2 provides recommendations on how to proceed if there is a compelling indication for the immediate use of a BLA. Reactions are classified into four risk categories on the basis of the temporal sequence reported in the patient history in immediate and delayed reactions and the severity of the symptoms. The color coding of severity is taken from the short patient’s history (Fig. 1). If a BLA allergy is ruled out based on the reported occurrence of non-allergic adverse drug reactions that are predictable and not severe, no allergy testing is required and BLA can be administered. In cases of reported clinical manifestations suspicious for mild, benign delayed reactions (type IV) without a severe cutaneous drug reaction, non-cross-reactive BLA can be directly administered at full dosage. If an immediate allergy (type I) with severe anaphylaxis is reported in the patient’s history, the administration of a non-BLA is recommended. In the case of a suspected immediate allergy (type I) with no severe anaphylaxis in the patient’s history, a non-cross-reactive BLA can be given in fractions (starting with one tenth of the single dose, followed by the full single dose 2 h later) with acceptable risk. However, an allergy specialist should always be consulted before drug administration in order to establish whether prior allergy testing, e.g., skin testing, is necessary. Any exposure to BLA, even non-cross-reactive BLA, in suspected allergy requires the patient to provide informed consent and to be monitored. In the case of suspected severe cutaneous and extracutaneous adverse drug reaction in the patient’s history, a non-BLA is given, since reactions of this kind are not predictable, cannot be adequately treated with drugs, and may follow a severe course.

The algorithm also provides recommendations on alternative treatment options and the evaluation of allergy testing, cross references to other important internal hospital documents (e.g., anti-infective guidelines, emergency cards), as well as contact details for the relevant points of contact (allergology, ABS unit, infectiology) and information on allergy documentation in patient records (e.g., de-labeling).

Discussion

Due to the disadvantages of treatment with non-BLA in suspected BLA allergy and the high number of unconfirmed cases of suspected allergy, a systematic approach to risk stratification is urgently required, not only for the authors’ university hospital. Since a risk stratification algorithm of this kind has not be described in Germany yet, the authors formulated recommendations on how to proceed in patients with suspected BLA allergy (Figs. 1 and 2). Reichel et al. took a similar approach using five partially subdivided questions to estimate the probability of BLA allergy and then recommend direct de-labeling or the use of an alternative antibiotic [16]. A hospital-wide basic patient’s history record is expected to be integrated in the electronic medical records of inpatients at the end of 2020, which will enable, among other things, centralized allergy documentation to be linked. The algorithm discussed here can provide valuable assistance in drawing up these records.

Early experience using the algorithm in clinical routine shows that a history of BLA allergy significantly hampers rational antibiotic therapy. This instrument shows clear clinical benefits, meaning that more patients with suspected BLA allergy can be treated with BLA. However, obstacles are also apparent, for which pragmatic solutions need to be developed and successively implemented in a multidisciplinary approach:

-

Collecting the required information from patient records and taking the patient history is time- and staff-intensive. Due to the intensification of work for medical personnel, the time factor will take on considerable importance in the future.

-

Information regarding “penicillin allergy” is generally based on the self-reported patient history. Once this information has been entered in the patient record, it will not necessarily be questioned or investigated at subsequent contacts with the patient. Precise information on symptoms of a BLA allergy are very rarely documented in patient records. It is often not possible for patients to provide specific data regarding, in particular, symptoms and times due to a lack of recalling the event often dating back to childhood. Patients frequently refer to the suspected antibiotic in an undifferentiated manner, using the umbrella term “penicillin”. Only a fraction of patients is able to reliably answer targeted questions about antibiotics that have been tolerated in the past.

-

Problems were primarily encountered in the retrospective description of cutaneous manifestations, in particular “urticaria/angioedema” versus “maculopapular exanthem”. As an aid to differentiation, picture cards (not shown) and bullet-point explanations (Table 1) were formulated, both for the physician’s use and for patients to use during history taking.

-

Patients often do not have their allergy pass with them (if they have one at all), often presenting these only when requested to do so and or with some delay after initial antibiotic therapy has been started.

-

The urgent recommendation to promptly carry out an outpatient investigation into a history of BLA allergy or an immediate reaction in the past is rarely followed. Therefore, a patient information leaflet, “Recommendation for allergy testing in suspected BLA allergy,” was developed in five different languages (German, English, Turkish, Arabic, and Russian) (Fig. 3). This was given to patients with a history of BLA allergy during allergy history taking. Inpatient allergy testing (skin testing plus/minus provocation testing) as standard in patients with equivocal BLA allergy in whom antibiotic therapy is compellingly indicated is only possible to a limited extent due to the spatial separation of the allergy department from the main hospital building. An optimized approach is currently under multidisciplinary discussion.

Conclusion

Heightening the awareness of suspected or proven beta-lactam antibiotic (BLA) allergies among treating physicians on the one hand and patients on the other is an essential task of the interdisciplinary antibiotic stewardship team in collaboration with the allergy unit. In addition to addressing BLA allergies in internal infection guidelines, training courses, and ABS (Antibiotic Stewardship) medical rounds, the risk stratification algorithm developed at the authors’ hospital represents a tool suited to making a contribution to rational antibiotic therapy. To ensure successful implementation, hurdles need to be continuously identified and interventions implemented in a targeted manner.

References

Wurpts G, Aberer W, Dickel H, Brehler R, Jakob T, Kreft B, et al. S2k Guideline: Diagnostics for suspected hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibiotics. Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI) in collaboration with the Medical Association of German Allergologists (AeDA), German Society for Pediatric Allergology and Environmental Medicine (GPA), the Austrian Society for Allergology and Immunology (ÖGAI), and the Paul-Ehrlich Society for Chemotherapy (PEG). Allergo J Int. 2019;28:121–51.

Brockow K. Triage strategies for clarifying reported betalactam allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1066–7.

Romano A, Atanaskovic-Markovic M, Barbaud A, Bircher AJ, Brockow K, Caubet JC, et al. Towards a more precise diagnosis of hypersensitivity to beta-lactams—an EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2019;75:1300–15.

Brockow K, Ardern-Jones MR, Mockenhaupt M, Aberer W, Barbaud A, Caubet JC, et al. EAACI position paper on how to classify cutaneous manifestations of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2019;74:14–27.

Vaisman A, McCready J, Hicks S, Powis J. Optimizing preoperative prophylaxis in patients with reported β‑lactam allergy: a novel extension of antimicrobial stewardship. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2657–60.

Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:742–7.

Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Wolfson AR, Berkowitz DN, Carballo VA, Balekian DS, et al. Addressing inpatient beta-lactam allergies: A multi-hospital implementation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:616–625.e7.

Blumenthal KG, Wickner PG, Hurwitz S, Pricco N, Nee AE, Laskowski K, et al. Tackling inpatient penicillin allergies: assessing tools for antimicrobial stewardship. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:154–161.e6.

Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321:188–99.

Devchand M, Urbancic KF, Khumra S, Douglas AP, Smibert O, Cohen E, et al. Pathways to improved antibiotic allergy and antimicrobial stewardship practice: the validation of a beta-lactam antibiotic allergy assessment tool. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1063–1065.e5.

Mohamed OE, Beck S, Huissoon A, Melchior C, Heslegrave J, Baretto R, et al. A retrospective critical analysis and risk stratification of penicillin allergy delabelling in a UK specialist regional allergy service. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:251–8.

Kuruvilla M, Sexton M, Wiley Z, Langfitt T, Lynde GC, Wolf F. A streamlined approach to optimize perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in the setting of penicillin allergy labels. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1316–22.

Savic LC, Khan DA, Kopac P, Clarke RC, Cooke PJ, Dewachter P, et al. Management of a surgical patient with a label of penicillin allergy: narrative review and consensus recommendations. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123:e82–e94.

du Plessis T, Walls G, Jordan A, Holland DJ. Implementation of a pharmacist-led penicillin allergy de-labelling service in a public hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:1438–46.

Brockow K, Przybilla B, Aberer W, Bircher AJ, Brehler R, Dickel H, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reactions: S2K-Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI) and the German Dermatological Society (DDG) in collaboration with the Association of German Allergologists (AeDA), the German Society for Pediatric Allergology and Environmental Medicine (GPA), the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group (DKG), the Swiss Society for Allergy and Immunology (SGAI), the Austrian Society for Allergology and Immunology (ÖGAI), the German Academy of Allergology and Environmental Medicine (DAAU), the German Center for Documentation of Severe Skin Reactions and the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Products (BfArM). Allergo J Int. 2015;24:94–105.

Reichel A, Röding K, Stoevesandt J, Trautmann A. De-labelling antibiotic allergy through five key questions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:532–5.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

C. Querbach, T. Biedermann, D.H. Busch, R. Eisenhart-Rothe, S. Feihl, C. Filser, F. Gebhardt, M. Heim, H. Renz, K. Rothe, C.D. Spinner, M. Starzner, C. Suren, M. Trojan and K. Brockow declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Querbach, C., Biedermann, T., Busch, D.H. et al. Suspected penicillin allergy: risk assessment using an algorithm as an antibiotic stewardship project. Allergo J Int 29, 174–180 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-020-00135-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-020-00135-5