Abstract

Physicians think of mast cells and IgE primarily in the context of allergic disorders, including fatal anaphylaxis. This ‘bad side’ of mast cells and IgE is so well accepted that it can be difficult to think of them in other contexts, particularly those in which they may have beneficial functions. However, there is evidence that mast cells and IgE, as well as basophils (circulating granulocytes whose functions partially overlap with those of mast cells), can contribute to host defense as components of adaptive type 2 immune responses to helminths, ticks and certain other parasites. Accordingly, allergies often are conceptualized as “misdirected” type 2 immune responses, in which IgE antibodies are produced against any of a diverse group of apparently harmless antigens, and against components of animal venoms. Indeed, certain unfortunate patients who have become sensitized to venoms develop severe IgE-associated allergic reactions, including fatal anaphylaxis, upon subsequent venom exposure. In this review, we will describe evidence that mast cells can enhance innate resistance, and survival, to challenge with reptile or arthropod venoms during a first exposure to such venoms. We also will discuss findings indicating that, in mice surviving an initial encounter with venom, acquired type 2 immune responses, IgE antibodies, the high affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI), and mast cells can contribute to acquired resistance to the lethal effects of both honeybee venom and Russell’s viper venom. These findings support the hypothesis that mast cells and IgE can help protect the host against venoms and perhaps other noxious substances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ABS:

-

rabbit anti-basophil serum

- AES:

-

rabbit anti-eosinophil serum

- BMCMCs:

-

bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells

- BV:

-

honeybee venom

- bvPLA2 :

-

honeybee venom phospholipase A2

- CBH:

-

cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity

- CPA3:

-

carboxypeptidase A3

- DNP:

-

dinitrophenol

- DNP-HSA:

-

dinitrophenol-conjugated human serum albumin

- ESCMCs:

-

embryonic stem cell-derived cultured mast cells

- ET‑1:

-

endothelin‑1

- F(ab):

-

antigen-binding fragment of an immunoglobulin molecule

- FcεRI:

-

the high affinity receptor for IgE

- i. d.:

-

intradermal

- i.p.:

-

intraperitoneal

- i.v.:

-

intravenous

- IgE:

-

immunoglobulin E (antibody)

- IgG:

-

immunoglobulin G (antibody)

- IL:

-

interleukin

- ILC2:

-

innate lymphoid cells, type 2

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

- MC(s):

-

mast cell(s)

- Mcl‑1:

-

myeloid cell leukemia 1

- MCP4:

-

mast cell protease 4

- NRS:

-

normal rabbit serum

- PAMPs:

-

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- RVV:

-

Russell’s viper venom

- s.c.:

-

subcutaneous

- shRNA:

-

small hairpin RNA

- Th2:

-

T helper cell type 2

- VIP:

-

vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

- WT:

-

wild type

References

Pawankar R, Canonica GW, Holgate ST, Lockey RF. Allergic diseases and asthma: a major global health concern. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:39–41.

Paul WE, Zhu J. How are TH2‑type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:225–35.

Galli SJ, Tsai M. IgE and mast cells in allergic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:693–704.

Pulendran B, Artis D. New paradigms in type 2 immunity. Science. 2012;337:431–5.

Kinet JP. The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:931–72.

Rivera J, Fierro NA, Olivera A, Suzuki R. New insights on mast cell activation via the high affinity receptor for IgE. Adv Immunol. 2008;98:85–120.

Oettgen HC, Geha RS. IgE in asthma and atopy: cellular and molecular connections. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:829–35.

Karasuyama H, Mukai K, Obata K, Tsujimura Y, Wada T. Nonredundant roles of basophils in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:45–69.

Sullivan BM, Liang HE, Bando JK, Wu D, Cheng LE, McKerrow JK, et al. Genetic analysis of basophil function in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:527–35.

Voehringer D. Protective and pathological roles of mast cells and basophils. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:362–75.

Kawakami T, Kitaura J. Mast cell survival and activation by IgE in the absence of antigen: a consideration of the biologic mechanisms and relevance. J Immunol. 2005;175:4167–73.

Boyce JA. Mast cells and eicosanoid mediators: a system of reciprocal paracrine and autocrine regulation. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:168–85.

Douaiher J, Succar J, Lancerotto L, Gurish MF, Orgill DP, Hamilton MJ, et al. Development of mast cells and importance of their tryptase and chymase serine proteases in inflammation and wound healing. Adv Immunol. 2014;122:211–52.

Galli SJ, Kalesnikoff J, Grimbaldeston MA, Piliponsky AM, Williams CM, Tsai M. Mast cells as “tunable” effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:749–86.

Metz M, Piliponsky AM, Chen CC, Lammel V, Abrink M, Pejler G, et al. Mast cells can enhance resistance to snake and honeybee venoms. Science. 2006;313:526–30.

Dawicki W, Marshall JS. New and emerging roles for mast cells in host defence. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:31–8.

Abraham SN, St. John AL. Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:440–52.

Akahoshi M, Song CH, Piliponsky AM, Metz M, Guzzetta A, Abrink M, et al. Mast cell chymase reduces the toxicity of Gila monster venom, scorpion venom, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4180–91.

Galli SJ, Borregaard N, Wynn TA. Phenotypic and functional plasticity of cells of innate immunity: macrophages, mast cells and neutrophils. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1035–44.

Jensen BM, Frandsen PM, Raaby EM, Schiotz PO, Skov PS, Poulsen LK. Molecular and stimulus-response profiles illustrate heterogeneity between peripheral and cord blood-derived human mast cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:893–901.

McNeil BD, Pundir P, Meeker S, Han L, Undem BJ, Kulka M, et al. Identification of a mast-cell-specific receptor crucial for pseudo-allergic drug reactions. Nature. 2015;519:237–41.

Portier MM, Richet C. De l’action anaphylactique de certains venims. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1902;54:170–2.

Finkelman FD. Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:506–15.

Stetson DB, Voehringer D, Grogan JL, Xu M, Reinhardt RL, Scheu S, et al. Th2 cells: orchestrating barrier immunity. Adv Immunol. 2004;83:163–89.

Finkelman FD, Shea-Donohue T, Morris SC, Gildea L, Strait R, Madden KB, et al. Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated host protection against intestinal nematode parasites. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:139–55.

Fitzsimmons CM, Dunne DW. Survival of the fittest: allergology or parasitology? Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:447–51.

Spencer LA, Porte P, Zetoff C, Rajan TV. Mice genetically deficient in immunoglobulin E are more permissive hosts than wild-type mice to a primary, but not secondary, infection with the filarial nematode Brugia malayi. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2462–7.

Schwartz C, Turqueti-Neves A, Hartmann S, Yu P, Nimmerjahn F, Voehringer D. Basophil-mediated protection against gastrointestinal helminths requires IgE-induced cytokine secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E5169–77.

Nawa Y, Kiyota M, Korenaga M, Kotani M. Defective protective capacity of W/Wv mice against strongyloides ratti infection and its reconstitution with bone marrow cells. Parasite Immunol. 1985;7:429–38.

Knight PA, Wright SH, Lawrence CE, Paterson YY, Miller HR. Delayed expulsion of the nematode trichinella spiralis in mice lacking the mucosal mast cell-specific granule chymase, mouse mast cell protease‑1. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1849–56.

Furuta T, Kikuchi T, Iwakura Y, Watanabe N. Protective roles of mast cells and mast cell-derived TNF in murine malaria. J Immunol. 2006;177:3294–302.

Maurer M, Lopez Kostka S, Siebenhaar F, Moelle K, Metz M, Knop J, et al. Skin mast cells control T cell-dependent host defense in Leishmania major infections. FASEB J. 2006;20:2460–7.

Ohnmacht C, Voehringer D. Basophils protect against reinfection with hookworms independently of mast cells and memory Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:344–50.

Arizono N, Kasugai T, Yamada M, Okada M, Morimoto M, Tei H, et al. Infection of nippostrongylus brasiliensis induces development of mucosal-type but not connective tissue-type mast cells in genetically mast cell-deficient Ws/Ws rats. Blood. 1993;81:2572–8.

Amiri P, Haak-Frendscho M, Robbins K, McKerrow JH, Stewart T, Jardieu P. Anti-immunoglobulin E treatment decreases worm burden and egg production in schistosoma mansoni-infected normal and interferon gamma knockout mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:43–51.

Newlands GF, Miller HR, MacKellar A, Galli SJ. Stem cell factor contributes to intestinal mucosal mast cell hyperplasia in rats infected with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis or Trichinella spiralis, but anti-stem cell factor treatment decreases parasite egg production during N brasiliensis infection. Blood. 1995;86:1968–76.

Holgate ST, Polosa R. Treatment strategies for allergy and asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:218–30.

Artis D, Maizels RM, Finkelman FD. Forum: immunology: allergy challenged. Nature. 2012;484:458–9.

Profet M. The function of allergy: immunological defense against toxins. Q Rev Biol. 1991;66:23–62.

Stebbings JH Jr.. Immediate hypersensitivity: a defense against arthropods? Perspect Biol Med. 1974;17:233–9.

Palm NW, Rosenstein RK, Medzhitov R. Allergic host defences. Nature. 2012;484:465–72.

Galli SJ. The 2014 Rous-Whipple award lecture. The mast cell-IgE paradox: from homeostasis to anaphylaxis. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:212–24.

Galli SJ, Colvin RB, Verderber E, Galli AS, Monahan R, Dvorak AM, et al. Preparation of a rabbit anti-guinea pig basophil serum: in vitro and in vivo characterization. J Immunol. 1978;121:1157–66.

Dvorak HF. Cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1976;58:229–40.

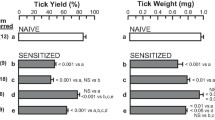

Brown SJ, Galli SJ, Gleich GJ, Askenase PW. Ablation of immunity to amblyomma americanum by anti-basophil serum: cooperation between basophils and eosinophils in expression of immunity to ectoparasites (ticks) in guinea pigs. J Immunol. 1982;129:790–6.

Childs JE, Paddock CD. The ascendancy of amblyomma americanum as a vector of pathogens affecting humans in the United States. Annu Rev Entomol. 2003;48:307–37.

Commins SP, James HR, Kelly LA, Pochan SL, Workman LJ, Perzanowski MS, et al. The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α‑1,3‑galactose. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1286–1293e6..

Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, Le QT, Berlin J, Morse M, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-α‑1,3‑galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1109–17.

Brown SJ, Askenase PW. Cutaneous basophil responses and immune resistance of guinea pigs to ticks: passive transfer with peritoneal exudate cells or serum. J Immunol. 1981;127:2163–7.

Allen JR. Tick resistance: basophils in skin reactions of resistant guinea pigs. Int J Parasitol. 1973;3:195–200.

Matsuda H, Watanabe N, Kiso Y, Hirota S, Ushio H, Kannan Y, et al. Necessity of IgE antibodies and mast cells for manifestation of resistance against larval haemaphysalis longicornis ticks in mice. J Immunol. 1990;144:259–62.

Wada T, Ishiwata K, Koseki H, Ishikura T, Ugajin T, Ohnuma N, et al. Selective ablation of basophils in mice reveals their nonredundant role in acquired immunity against ticks. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2867–75.

Steeves EB, Allen JR. Basophils in skin reactions of mast cell-deficient mice infested with dermacentor variabilis. Int J Parasitol. 1990;20:655–67.

Chabot B, Stephenson DA, Chapman VM, Besmer P, Bernstein A. The proto-oncogene c‑kit encoding a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus. Nature. 1988;335:88–9.

Geissler EN, Ryan MA, Housman DE. The dominant-white spotting (W) locus of the mouse encodes the c‑kit proto-oncogene. Cell. 1988;55:185–92.

Kitamura Y, Go S, Hatanaka K. Decrease of mast cells in W/Wv mice and their increase by bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1978;52:447–52.

Russell ES. Hereditary anemias of the mouse: a review for geneticists. Adv Genet. 1979;20:357–459.

Harrison DE, Astle CM. Population of lymphoid tissues in cured W‑anemic mice by donor cells. Transplantation. 1976;22:42–6.

Nakano T, Waki N, Asai H, Kitamura Y. Lymphoid differentiation of the hematopoietic stem cell that reconstitutes total erythropoiesis of a genetically anemic W/Wv mouse. Blood. 1989;73:1175–9.

Nakano T, Waki N, Asai H, Kitamura Y. Different repopulation profile between erythroid and nonerythroid progenitor cells in genetically anemic W/Wv mice after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1989;74:1552–6.

Nabel G, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF, Cantor H. Inducer T lymphocytes synthesize a factor that stimulates proliferation of cloned mast cells. Nature. 1981;291:332–4.

Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Marcum JA, Ishizaka T, Nabel G, Der Simonian H, et al. Mast cell clones: a model for the analysis of cellular maturation. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:435–44.

Nakano T, Sonoda T, Hayashi C, Yamatodani A, Kanayama Y, Yamamura T, et al. Fate of bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells after intracutaneous, intraperitoneal, and intravenous transfer into genetically mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice. Evidence that cultured mast cells can give rise to both connective tissue type and mucosal mast cells. J Exp Med. 1985;162:1025–43.

Tsai M, Wedemeyer J, Ganiatsas S, Tam SY, Zon LI, Galli SJ. In vivo immunological function of mast cells derived from embryonic stem cells: an approach for the rapid analysis of even embryonic lethal mutations in adult mice in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9186–90.

Maurer M, Wedemeyer J, Metz M, Piliponsky AM, Weller K, Chatterjea D, et al. Mast cells promote homeostasis by limiting endothelin-1-induced toxicity. Nature. 2004;432:512–6.

Piliponsky AM, Chen CC, Nishimura T, Metz M, Rios EJ, Dobner PR, et al. Neurotensin increases mortality and mast cells reduce neurotensin levels in a mouse model of sepsis. Nat Med. 2008;14:392–8.

Galli SJ, Kitamura Y. Genetically mast-cell-deficient W/Wv and Sl/Sld mice. Their value for the analysis of the roles of mast cells in biologic responses in vivo. Am J Pathol. 1987;127:191–8.

Grimbaldeston MA, Chen CC, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tam SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient W‑sash c‑kit mutant KitW‑sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:835–48.

Wolters PJ, Mallen-St. Clair J, Lewis CC, Villalta SA, Baluk P, Erle DJ, et al. Tissue-selective mast cell reconstitution and differential lung gene expression in mast cell-deficient KitW‑sh/KitW‑sh sash mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:82–8.

Lilla JN, Chen CC, Mukai K, BenBarak MJ, Franco CB, Kalesnikoff J, et al. Reduced mast cell and basophil numbers and function in Cpa3-Cre; Mcl‑1fl/fl mice. Blood. 2011;118:6930–8.

Metz M, Grimbaldeston MA, Nakae S, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells in the promotion and limitation of chronic inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:304–28.

Galli SJ, Tsai M, Marichal T, Tchougounova E, Reber LL, Pejler G. Approaches for analyzing the roles of mast cells and their proteases in vivo. Adv Immunol. 2015;126:45–127.

Nigrovic PA, Gray DH, Jones T, Hallgren J, Kuo FC, Chaletzky B, et al. Genetic inversion in mast cell-deficient Wsh mice interrupts corin and manifests as hematopoietic and cardiac aberrancy. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1693–701.

Brown MA, Hatfield JK. Mast cells are important modifiers of autoimmune disease: with so much evidence, why is there still controversy? Front Immunol. 2012;3:147.

Rodewald HR, Feyerabend TB. Widespread immunological functions of mast cells: fact or fiction? Immunity. 2012;37:13–24.

Higginbotham RD. Mast cells and local resistance to Russell’s viper venom. J Immunol. 1965;95:867–75.

Higginbotham RD, Karnella S. The significance of the mast cell response to bee venom. J Immunol. 1971;106:233–40.

Kloog Y, Ambar I, Sokolovsky M, Kochva E, Wollberg Z, Bdolah A. Sarafotoxin, a novel vasoconstrictor peptide: phosphoinositide hydrolysis in rat heart and brain. Science. 1988;242:268–70.

Kochva E, Bdolah A, Wollberg Z. Sarafotoxins and endothelins: evolution, structure and function. Toxicon. 1993;31:541–68.

Fry BG. From genome to “venome”: molecular origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences and related body proteins. Genome Res. 2005;15:403–20.

Schneider LA, Schlenner SM, Feyerabend TB, Wunderlin M, Rodewald HR. Molecular mechanism of mast cell mediated innate defense against endothelin and snake venom sarafotoxin. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2629–39.

Tchougounova E, Pejler G, Abrink M. The chymase, mouse mast cell protease 4, constitutes the major chymotrypsin-like activity in peritoneum and ear tissue. A role for mouse mast cell protease 4 in thrombin regulation and fibronectin turnover. J Exp Med. 2003;198:423–31.

Wernersson S, Pejler G. Mast cell secretory granules: armed for battle. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:478–94.

Anderson E, Stavenhagen K, Kolarich D, Sommerhoff CP, Maurer M, Metz M. Human mast cell tryptase is a potential treatment for snakebite envenoming across multiple snake species. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1532.

Neves-Ferreira AG, Perales J, Fox JW, Shannon JD, Makino DL, Garratt RC, et al. Structural and functional analyses of DM43, a snake venom metalloproteinase inhibitor from didelphis marsupialis serum. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13129–37.

Habermann E. Bee and wasp venoms. Science. 1972;177:314–22.

Mukherjee AK, Ghosal SK, Maity CR. Some biochemical properties of Russell’s viper (daboia russelli) venom from eastern India: correlation with clinico-pathological manifestation in Russell’s viper bite. Toxicon. 2000;38:163–75.

Risch M, Georgieva D, von Bergen M, Jehmlich N, Genov N, Arni RK, et al. Snake venomics of the siamese Russell’s viper (daboia russelli siamensis)—relation to pharmacological activities. J Proteomics. 2009;72:256–69.

Saelinger CB, Higginbotham RD. Hypersensitivity responses to bee venom and the mellitin. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1974;46:28–37.

Charavejasarn CC, Reisman RE, Arbesman CE. Reactions of anti-bee venom mouse reagins and other antibodies with related antigens. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1975;48:691–7.

Jarisch R, Yman L, Boltz A, Sandor I, Janitsch A. IgE antibodies to bee venom, phospholipase A, melittin and wasp venom. Clin Allergy. 1979;9:535–41.

Wadee AA, Rabson AR. Development of specific IgE antibodies after repeated exposure to snake venom. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;80:695–8.

Annila I. Bee venom allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1682–7.

Bilo BM, Rueff F, Mosbech H, Bonifazi F, Oude-Elberink JN. Diagnosis of hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy. 2005;60:1339–49.

Simpson ID, Norris RL. Snakes of medical importance in India: is the concept of the “big 4” still relevant and useful? Wilderness Environ Med. 2007;18:2–9.

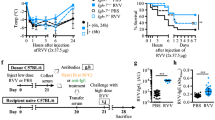

Marichal T, Starkl P, Reber LL, Kalesnikoff J, Oettgen HC, Tsai M, et al. A beneficial role for immunoglobulin E in host defense against honeybee venom. Immunity. 2013;39:963–75.

Oettgen HC, Martin TR, Wynshaw-Boris A, Deng C, Drazen JM, Leder P. Active anaphylaxis in IgE-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;370:367–70.

Miyajima I, Dombrowicz D, Martin TR, Ravetch JV, Kinet JP, Galli SJ. Systemic anaphylaxis in the mouse can be mediated largely through IgG1 and FcγRIII. Assessment of the cardiopulmonary changes, mast cell degranulation, and death associated with active or IgE- or IgG1-dependent passive anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:901–14.

Reimers AR, Weber M, Muller UR. Are anaphylactic reactions to snake bites immunoglobulin E‑mediated? Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:276–82.

Meier J. Commercially available antivenoms (“hyperimmune sera”, “antivenins”, “antisera”) for antivenom therapy. In: Meier J, White J, editors. Handbook of clinical toxicology of animal venoms and poisons. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 689–721.

Haak-Frendscho M, Saban R, Shields RL, Jardieu PM. Anti-immunoglobulin E antibody treatment blocks histamine release and tissue contraction in sensitized mice. Immunology. 1998;94:115–21.

Prouvost-Danon A, Binaghi RA, Abadie A. Effect of heating at 56 degrees C on mouse IgE antibodies. Immunochemistry. 1977;14:81–4.

Strait RT, Morris SC, Finkelman FD. IgG-blocking antibodies inhibit IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in vivo through both antigen interception and FcγRIIb cross-linking. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:833–41.

Palm NW, Rosenstein RK, Yu S, Schenten DD, Florsheim E, Medzhitov R. Bee venom phospholipase A2 induces a primary type 2 response that is dependent on the receptor ST2 and confers protective immunity. Immunity. 2013;39:976–85.

Starkl P, Marichal T, Gaudenzio N, Reber LL, Sibilano R, Tsai M, et al. IgE antibodies, FcεRIα and IgE-mediated local anaphylaxis can limit snake venom toxicity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:246–57.

Habermann E, Walsch P, Breithaupt H. Biochemistry and pharmacology of the cortoxin complex. II. possible interrelationships between toxicity and organ distribution of phospholipase A, crotapotin and their combination. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1972;273:313–30.

Liu FT, Bohn JW, Ferry EL, Yamamoto H, Molinaro CA, Sherman LA, et al. Monoclonal dinitrophenyl-specific murine IgE antibody: preparation, isolation, and characterization. J Immunol. 1980;124:2728–37.

Bruhns P. Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood. 2012;119:5640–9.

Cavalcante MC, de Andrade LR, Du Bocage Santos-Pinto C, Straus AH, Takahashi HK, Allodi S, et al. Colocalization of heparin and histamine in the intracellular granules of test cells from the invertebrate styela plicata (chordata-tunicata). J Struct Biol. 2002;137:313–21.

Wong GW, Zhuo L, Kimata K, Lam BK, Satoh N, Stevens RL. Ancient origin of mast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;451:314–8.

de Barros CM, Andrade LR, Allodi S, Viskov C, Mourier PA, Cavalcante MC, et al. The Hemolymph of the ascidian styela plicata (chordata-tunicata) contains heparin inside basophil-like cells and a unique sulfated galactoglucan in the plasma. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1615–26.

Fry BG, Roelants K, Champagne DE, Scheib H, Tyndall JDA, King GF, et al. The toxicogenomic multiverse: convergent recruitment of proteins into animal venoms. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:483–511.

Antonicelli L, Bilo MB, Bonifazi F. Epidemiology of hymenoptera allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:341–6.

Muller UR. Bee venom allergy in beekeepers and their family memberws. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:343–7.

Meiler F, Zumkehr J, Klunker S, Ruckert B, Akdis CA, Akdis M. In vivo switch to IL-10-secreting T regulatory cells in high dose allergen exposure. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2887–98.

Ozdemir C, Kucuksezer UC, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Mechanisms of immunotherapy to wasp and bee venom. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1226–34.

Acknowledgements

We thank the past and current members of the Galli lab and the many collaborators who have made important contributions to the work reviewed herein. The work reviewed herein was supported by grants to S.J.G. from the National Institutes of Health (e.g., R37 AI23990, R01 CA072074, R01 AR067145, and U19 AI104209) and the National Science Foundation, and from several other funding sources, including the Department of Pathology at Stanford University. M.M. was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG, ME 2668/3‑2, ME 2668/2-1) and the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Foundation, P.S. was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P31113-B30, a Max Kade Fellowship of the Max Kade Foundation and the Austrian Academy of Sciences, a Schroedinger Fellowship of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): J3399-B21, and a Marie Curie fellowship of the European Commission (H2020-MSCA-IF-2014), 655153. T.M. was supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship for Career Development: European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-PEOPLE-2011-IOF), 299954, and a “Charge de recherches” fellowship of the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S-FNRS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S.J. Galli, M. Metz, P. Starkl, T. Marichal and M. Tsai declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

This review is a modified and updated version of similar invited reviews that appeared in the American Journal of Pathology: Galli SJ: The 2014 Rous-Whipple Award Lecture. The mast cell-IgE paradox: From homeostasis to anaphylaxis. Am J Pathol, 2016; 186:212–224. PMID: 26776074 and in Allergology International: Galli SJ, Starkl P, Marichal T, Tsai M. Mast cells and IgE in defense against venoms: Possible “good side” of allergy. Allergol Int 2016; 65:3–15. PMID: 26666482. This article is based in part on a keynote lecture given by Stephen J. Galli on April 11, 2019 at the EAACI Allergy School on Insect Venom Allergy and Mastocytosis in Groningen, The Netherlands.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Galli, S.J., Metz, M., Starkl, P. et al. Mast cells and IgE in defense against lethality of venoms: Possible “benefit” of allergy. Allergo J Int 29, 46–62 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-020-00118-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-020-00118-6