Abstract

Background

Understanding the behaviours that facilitate or impede one’s ability to self-manage is important to improve health-related outcomes in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). Previous studies exploring the self-management experiences of KTRs have focused on specific tasks (e.g., medication adherence), age groups (e.g., adolescent or older recipients), or have been conducted outside of the UK where transferability of findings is unknown. Our study aimed to explore the perceptions and experiences of self-management in UK KTRs to identify facilitators and barriers associated with self-management tasks.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with eleven KTRs. Topics explored included experiences of self-management tasks (diet, exercise, medications, stress management), perceived healthcare role, and future interventional approaches. Thematic analysis was used to identify and report themes.

Results

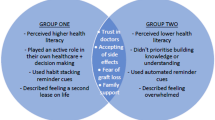

Eight themes were identified which were mapped onto the three self-management tasks described by Corbin and Strauss: medical, role and emotional management. Perceived facilitators to self-management were: gathering health-related knowledge, building relationships with healthcare professionals, creating routines within daily life, setting goals and identifying motivators, establishing support networks, and support from family and friends. Complexity of required treatment and adjusting to a new health status were perceived barriers to self-management.

Conclusions

Participants described the importance of collaborative consultations and continuity of care. Tailored interventions should identify individualised goals and motivators for participating in self-management. Education on effective strategies to manage symptoms and comorbidities could help alleviate KTRs’ perceived treatment burden. Family and peer support could emotionally support KTRs; however, managing the emotional burden of transplantation warrants more attention.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Kidney transplantation offers better long-term health outcomes [1, 2] and reduced mortality [3] than dialysis for individuals with end-stage kidney disease. However, morbidity and quality of life in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) continues to remain inferior to those without chronic kidney disease (CKD) [4]. To reduce the risk of long-term complications associated with transplantation, including graft failure, KTRs are encouraged to engage with their healthcare and take greater responsibility for their health [5]; this is termed self-management [6]. KTRs who engage in self-management behaviours have improved clinical markers and report better medication adherence [7]. Self-management comprises of three core tasks: medical, role, and emotional management [8]. For KTRs, medical management includes adherence to complex medication regimens, self-assessment for symptoms and complications, attending appointments and cancer screening, and avoidance of unwell individuals [5, 9]. Emotional management describes dealing with the negative emotions of their condition such as fear of graft failure. Role management includes social and behavioural adaptations, such as eating a balanced diet, maintaining hydration and regular physical activity [9].

Engagement in self-management behaviours in KTRs remain poor, with studies reporting low levels of physical activity [10], inconsistent dietary adherence [11], and high levels of medication non-adherence [12]. Understanding the facilitators and barriers towards effective self-management can aid in the development of targeted resources to support these behaviours. A qualitative systematic review of motivations, challenges, and attitudes in KTRs identified themes relating to the overarching perspectives of self-management such as burdensome treatment, responsibilities, and empowerment through autonomy [9]. Despite synthesising fifty studies, many included only explored specific experiences relating to single aspect of self-management (e.g., medication adherence, stressors and coping strategies, and post-operative recovery) [13,14,15,16]. Other studies exploring self-management in KTRs have excluded key groups such as individuals less than one-year post-transplantation [17], a population of key importance due to their vulnerability to graft loss and death [18]. Research has also focused on specific age groups such as adolescents [19] or older KTRs [20]. Been-Dahmen et al. [21] explored the self-management challenges and support needs of KTRs and utilised the three self-management tasks described by Corbin and Strauss [8] when both designing and reporting their study. However, due to being conducted at a single centre in the Netherlands, and subsequently having a majority Dutch sample (81.3%), it is important to understand how their findings may transfer to other KTR populations.

To date, no studies have reported KTRs’ experiences alongside an assessment to quantify individuals perceived self-management ability. The ‘Patient Activation Measure’ (PAM) assesses individuals’ perceived ability to manage their own health and care [22]. The important role of the PAM in understanding self-management behaviours in KTRs has been recognized in the United Kingdom (UK) [23, 24], and was recommended to inform kidney disease policy in the United States [25]. A recent report suggests that the PAM could be pivotal when developing patient-centred self-management interventions for KTRs, and could inform interview topics and facilitate the representation of the experiences of those with different self-management abilities [25].

With self-management tasks changing considerably post-transplantation, there is a need to understand the overall experiences, facilitators, and barriers of self-management to inform healthcare professionals (HCPs) on how to deliver effective tailored support to KTRs. The purpose of this study was to explore the facilitators and barriers towards self-management in a UK KTR population.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This is a qualitative sub-study of DIMENSION-KD (ISRCTN84422148), a national multi-site prospective observational research study. Participants were recruited from routine outpatient clinics at the Leicester General Hospital, UK. For this study, the inclusion criteria were ≥ 18 years of age, a functioning kidney transplant, and the ability to provide written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were CKD Stages 1–5 without transplantation.

The aim was to recruit 12 participants; this sample size was chosen to reflect sufficient diversity in views and experiences within the available time and resources. This number reflected guidelines created to ensure an appropriate sample size [26], and was subject to change throughout the interview process as it was dependant on the richness of data derived from individual participants [27]. In order to capture diversity in responses, participants were recruited using purposive sampling, utilising maximum variation sampling to ensure a representative population with a range of characteristics [28].

Those invited to be interviewed were contacted by phone or email, using details provided by participants, to arrange a suitable time for interview. Ethical approval was provided by the East-Midlands Leicester Central Research Ethics Committee (18/EM/0117). Written informed consent was obtained prior to the commencement of the interview. Transcripts were anonymised and IDs were given to participants.

Consent was obtained to access clinical data (eGFR, years since receiving transplant) from medical notes and questionnaire results (age, ethnicity, employment status, PAM score) from a different part of the research study. Patient activation was assessed by the PAM—where individuals answered thirteen statements relating to health behaviours on a Likert scale (disagree strongly, disagree, agree, agree strongly or N/A). PAM scores between 0 and 100 were calculated [22, 29] to categorise participants into one of four activation levels; Level 1 (< 47.0, lowest), Level 2 (47.1–55.1), Level 3 (55.2–67.0), Level 4 (> 67.0, highest) [22, 30]. PAM has been validated and recommended for use in KTRs [31].

Interview procedure

Individual semi-structured interviews were used to explore the perceptions and experiences of self-management. An interview schedule was developed through familiarisation with current literature, exploring the three self-management tasks described by Corbin and Strauss [8], and also reflecting core statements within the PAM (skills, knowledge and confidence). A renal pharmacist provided insights into medication regimens, and two KTRs provided further feedback on the types of self-management tasks to be discussed. Minor revisions were made prior to conducting interviews to reflect topics that emerged (e.g., perceived role of family members in KTRs’ care). The schedule was pilot tested with a KTR to ensure that the interview schedule was appropriate, easily understood, and functional. As the pilot interview was data-rich, it was subsequently included in the final analysis.

Interviews were conducted face-to-face within a quiet meeting room in the research department, between October 2019 and February 2020, by a medical student (KEM) completing a master’s project with the research team. An experienced qualitative researcher (CJL) observed two interviews. Participants had no previous relationship with the researchers prior to study commencement. KEM kept a personal reflective logbook during interview conduction and analysis. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company.

Qualitative analysis

QSR International’s NVivo9 software was used to manage the data, which were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis, described by Braun and Clarke [32, 33]. KEM familiarised themself with the complete data set through listening to audio-recordings and annotating transcripts, and independently identified initial codes using an inductive approach. A sample of transcripts were independently coded by CJL. Following confirmation of similar code derivation, the remaining transcripts were coded by KEM. Potential themes were created through identifying relationships between codes, re-focusing and collating them to form over-arching concepts. CJL refined themes with KEM throughout this process, and definitions of themes were agreed. It was recognised that emerging themes were strongly linked to the three self-management tasks by Corbin and Strauss [8], and was likely reflective of the tasks being embedded within the interview schedule. Thus, to provide structured demonstration of findings, themes were mapped onto these tasks, and relevant quotes were selected to illustrate the findings. The COREQ guidelines were followed when reporting the methods.

Findings

Summary of participant characteristics

Twenty-nine KTRs were invited to participate, 18 of whom responded: two declined to take part and two were uncontactable. Further recruitment ceased due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Thus, a total of 11 interviews were conducted. Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Interviewees comprised of eight males and three females, with a mean age of 55 (range 33–77) years. The mean eGFR was 48.0 (± 21.2) mL/min/1.73 m2. PAM scores ranged from 51.0 to 100 (Levels 2–4).

Interview duration ranged from 48 to 86 min (mean 68 min). Participants described their role in self-managing their health and kidney transplant. Eight themes were identified and, to both provide a structured display of findings and reflect the integral role of these tasks in exploring our research question, they were mapped onto their relevant task described by Corbin and Strauss [8]. Interviews prioritised exploring motivators to self-management and so more facilitators than barriers were identified. Themes present both barriers and facilitators within them and are displayed with relevant quotes in tables relating to their associated self-management task.

Task 1: Medical management

Exemplar quotes are presented in Table 2

Theme 1: Gathering health-related knowledge

Participants believed that having knowledge of their condition and an awareness of how to self-manage increased their confidence to undertake self-management tasks. Self-management knowledge was considered to increase with the progression of time since their transplant, as a result of engaging more in their healthcare. The desired amount of information to effectively self-manage varied, with some considering excess knowledge as a source of anxiety, and others wanted more.

Theme 2: Complexity of required treatment

The combined burden of symptoms, medication side effects, underlying kidney condition, and comorbidities were considered to limit engagement with self-management. Participants with multiple conditions believed that General Practitioners (GPs) had insufficient time to support each condition effectively. Complications such as infections were described as disabling, with long hospital stays resulting in negative impact on mental health and exacerbated symptom burden. Fatigue was considered as a debilitating symptom which limited activities and could only be relieved by resting. Some participants reported being unable to complete daily tasks or maintain employment due to their symptom burden.

Task 2: Role management

Exemplar quotes are presented in Table 3

Theme 3: Building relationships with healthcare professionals

Participants believed that establishing relationships with HCPs helped build trust, supported them to feel involved with healthcare decisions and enabled the delivery of tailored advice. These relationships were formed through collaborative consultations with HCPs and continuity of clinical support. Ease of access to medical support was considered to be reassuring to participants, and HCPs who took responsibility for their patients, answered questions, provided manageable recommendations, and empowered patients were perceived to offer good quality care.

Theme 4: Creating routines within daily life

Medication, dietary, and exercise routines were perceived to facilitate self-management by integrating tasks into daily life. Most participants described adjusting medication routines around meals or work schedules, with some participants utilising dosette boxes and alarms as reminders; preparing for routine disruptions, such as holidays or life-events, were considered to ensure consistency.

Theme 5: Setting goals and identifying motivators

Goals were reported to motivate participants to self-manage, and included weight loss, exercise consistency, and high fluid intake, which participants tracked themselves or by using apps. Whilst some participants felt discouraged when they were not achieved and believed that goals restricted their lifestyles, many discussed how they provided an endpoint to persevere towards. Family members, career aspirations, inspiring stories from other KTRs, and aspiring for a long graft lifespan were considered motivators to engage in self-management behaviours.

Task 3: Emotional management

Exemplar quotes are presented in Table 4

Theme 6: Adjusting to a new health status

Most participants discussed the emotional impact of receiving a transplant and their fears of graft loss. Managing complex health recommendations and adjusting to reduced restrictions in the early post-transplant phase was considered to be overwhelming, impacting upon participants’ mental health. Nearly all participants described feeling vulnerable and anxious due to missed medications or complications. Participants were fearful of harming their graft, especially when exercising, being around unwell individuals, or in crowds of people.

Theme 7: Support from family and friends

Almost all participants expressed a desire for family and friends to receive education on their condition, the emotional impact of receiving a transplant, and how to assist with self-management behaviours. Many participants believed that having family members attend their appointments helped them to understand their condition better, provided appropriate emotional support, and supported participants to engage more with their health.

Theme 8: Establishing peer support networks

A small number of participants explained that they avoided seeking peer support because they previously encountered scaremongering and negativity. Nevertheless, the majority of participants described experiencing a ‘community’ when engaging with other KTRs and they suggested that providing support groups, online forums, and patient information days could emotionally support KTRs.

Discussion

In this study, we report the facilitators and barriers to self-management in KTRs. This information is key to understanding how to improve self-management behaviours in individuals. Through reporting participant PAM levels, our study provides further information on each individual’s perceived self-management abilities to complement the understanding gained from their lived experiences. Our findings demonstrate that effective self-management requires support to complete each of the three self-management tasks described by Corbin and Strauss [8]: medical, role, and emotional management. Gathering sufficient information on how to self-manage was described as meaningful to undertake medical management, whilst individual’s symptom burden, complications, and comorbidities were considered barriers. Role management was facilitated by establishing relationships with HCPs, building routines, setting goals, identifying motivators, and integrating both peer and family support networks into individuals’ healthcare. Emotional management was considered to be adversely impacted by the emotional burden of transplantation, including fear of graft failure and individuals’ perceived vulnerability.

Establishing relationships with HCPs was facilitated through collaborative consultations, continuity of care, and empowerment from HCPs and appeared to influence individuals’ health-related knowledge. The importance of developing partnerships, shared decision-making, and desired qualities of HCPs has been discussed within other KTR populations [21, 34]. Active interactions with HCPs can empower individuals and nurture intrinsic motivation, defined as the completion of tasks for personal satisfaction [35]. With intrinsic motivation being a prominent motivator for behavioural change [36], HCPs should actively listen to their patients’ descriptions of their lifestyles and integrate recommendations based on their desired outcomes. These consultations could involve the creation of action plans which identify realistic and tailored health targets [35, 37] to increase recipients’ self-efficacy (an individual’s confidence and beliefs in their capabilities to complete tasks) [38].

Participants discussed the importance of identifying motivators to engage with self-management and setting health-related goals. The significance of KTRs setting goals to achieve weight loss has been previously mentioned [39]; however, the motivating factor for participants to reach targets varied: some strived for looser fitting clothes whilst others were motivated by weight reductions on scales. Our study similarly found that motivators were diverse and influenced by previous experiences, circumstances, and beliefs. Individualised techniques to promote self-efficacy, including motivational interviewing or developing action plans, could influence self-management behaviours in KTRs [40]. Whilst priorities can differ with donor type, with individuals receiving a live donation feeling obligated to care for themselves and those who receive a deceased donation can be motivated by guilt [9], this was not discussed by our participants. Further research may be required to explore differences in self-management behaviours between those who receive a live donation, both related and unrelated, and those who receive a deceased donation.

The routinising of diet, exercise, and medication regimens were perceived to facilitate consistent engagement with self-management. Similar routines have been discussed in other KTR populations, particularly relating to medication regimens [16, 17, 41, 42]. Like other studies [16, 41, 42], our participants emphasised that their routines are dynamic and prone to change with holidays or life-events, and so they utilise reminders (e.g., alarms or taking medications earlier/later) to overcome potential disruptions. Tailored recommendations based on individuals’ lifestyles and promote self-regulation of adherence behaviours to promote consistent self-management [43].

Social support networks were considered to encourage participants to actively engage during consultations and supported healthy eating and exercise. Family support can promote healthy behaviours [17], and engaging the family within KTRs’ care could be further prioritised by providing education on supporting self-management tasks and exploring the concerns of the family. Social support should be integrated with consideration as disparities in their perceived illness states means some KTRs have experienced limited emotional support from relatives [34]. Similar to other studies, peer support was not universally desired by participants [21], and some avoided due to ‘scaremongering’ [44]. However, talking to other KTRs can validate concerns and facilitate the sharing of knowledge. Reviews of one-to-one peer-led support in CKD patients received positive acclaim with interactions described as providing hope, reassurance and encouragement [45]. Such peer-led programmes or larger support groups could be integrated into KTRs’ care pathways, with a focus on managing the emotional barriers experienced, including how to adjust from prior restrictions, worries about engaging with exercise, coping with anxiety-provoking situations, and how to overcome negative emotions.

Fatigue, breathlessness, and pain were prevalent amongst participants and were considered to limit their ability to engage in self-management tasks and daily activities. Symptom burden has similarly reduced physical function in other KTR populations [39, 46], with older-aged KTRs feeling frustrated when complications, comorbidities, and reduced physical function persist following transplantation [20]. The emotional and physical burden of these factors may influence KTRs’ abilities to self-manage, therefore it remains imperative to understand the individuals’ perceived treatment burden. Routine assessment of patients’ symptoms and comorbidities could inform tailored education of their management.

Managing the prevalent and complex emotional impact of transplantation warrants more attention. Our participants described feeling overwhelmed and vulnerable post-transplantation, experiencing fear when engaging in daily activities. Heightened emotional responses immediately following transplantation [15, 44, 47], and distress following potential changes or complications post-transplantation [9] have previously been reported. Guidance and reassurance on how to safely re-engage in self-management activities (e.g., their bodies’ physical limitations and activity recommendations), and signposting to psychological interventions [14] could support KTRs.

The main limitation is that interviews were conducted at one-time point. Self-management behaviours are likely to change over time so responses may change depending on factors such as time since transplant or complications. Some participants had recently received a transplant; therefore, their self-management may not have been as well-established as other interviewees. This study was conducted as part of a master’s project with data collection limitations further impeded by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, data were rich in experiences and analysis reflected a thorough exploration of the research question. As proposed by Braun and Clarke [48], we provide detailed descriptors of our analysis process as an alternative to commenting on data saturation, due to the concept not aligning with our reflexive thematic analysis stance. Additionally, we recognise the limitations of transferability with a majority male and Caucasian sample; however, the samples were a good reflection of the larger DIMENSION-KD study (n = 743) (our study 73% versus 68% male; 73% Caucasian versus 94% White British) [49]. Further efforts to explore experiences of other ethnic groups is needed. In addition, exploring the experiences of socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals, older individuals, and paediatric KTRs would merit consideration in future research.

Conclusion

More facilitators than barriers to self-management were reported by KTRs. This study demonstrates the importance of understanding lived experiences and perceived needs to tailor self-management support. KTRs experience facilitators and barriers in all aspects of self-management indicating that that holistic care should address all self-management components; medical, role, and emotional management. Greater focus should be given to support role and emotional management in this population.

References

Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G et al (2011) Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transpl 11(10):2093–2109

Purnell TS, Auguste P, Crews DC et al (2013) Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 62(5):953–973

Kaballo MA, Canney M, O’Kelly P, Willians Y, O’Seaghdha CM, Conlon PJ (2018) A comparative analysis of survival of patients on dialysis and after kidney transplantation. Clin Kidney J 11(3):389–393

Hernandez Sanchez S, Carrero JJ, Garcia Lopez D, Herrero Alonso JA, Menendez Alegre H, Ruiz JR (2016) Fitness and quality of life in kidney transplant recipients: case-control study. Med Clin (Barc) 146(8):335–338

Gordon EJ, Prohaska T, Siminoff LA, Minich PJ, Sehgal AR (2005) Can focusing on self-care reduce disparities in kidney transplantation outcomes? Am J Kidney Dis 45(5):935–940

Lorig KR, Holman H (2003) Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 26(1):1–7

Ganjali R, Khoshrounejad F, Mazaheri Habibi MR et al (2019) Effect and features of information technology-based interventions on self-management in adolescent and young adult kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Adolesc Health Med Ther 10:173–190

Corbin JM, Strauss A (1988) Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Fransisco

Jamieson NJ, Hanson CS, Josephson MA et al (2016) Motivations, challenges, and attitudes to self-management in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 67(3):461–478

Gustaw T, Schoo E, Barbalinardo C et al (2017) Physical activity in solid organ transplant recipients: participation, predictors, barriers, and facilitators. Clin Transpl 31(4):e12929

Nolte Fong JV, Moore LW (2018) Nutrition trends in kidney transplant recipients: the importance of dietary monitoring and need for evidence-based recommendations. Front Med (Lausanne) 5:302–302

Cossart AR, Staatz CE, Campbell SB, Isbel NM, Cottrell WN (2019) Investigating barriers to immunosuppressant medication adherence in renal transplant patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 24(1):102–110

Amerena P, Wallace P (2009) Psychological experiences of renal transplant patients: a qualitative analysis. Couns Psychother Res 9(4):273–279

Baines LS, Joseph JT, Jindal RM (2002) Emotional issues after kidney transplantation: a prospective psychotherapeutic study. Clin Transpl 16(6):455–460

Gill P (2012) Stressors and coping mechanisms in live-related renal transplantation. J Clin Nurs 21(11–12):1622–1631

Orr A, Orr D, Willis S, Holmes M, Britton P (2007) Patient perceptions of factors influencing adherence to medication following kidney transplant. Psychol Health Med 12(4):509–517

Ndemera H, Bhengu BR (2017) Motivators and barriers to self-management among kidney transplant recipients in selected state hospitals in South Africa: a qualitative study. Health Sci J 11(5):527

Farrugia D, Cheshire J, Begaj I, Khosla S, Ray D, Sharif A (2014) Death within the first year after kidney transplantation: an observational cohort study. Transpl Int 27(3):262–270

Tong A, Morton R, Howard K, McTaggart S, Craig JC (2011) “When I had my transplant, I became normal”. Adolescent perspectives on life after kidney transplantation. Pediatr Transpl 15(3):285–293

Pinter J, Hanson CS, Chapman JR et al (2017) Perspectives of older kidney transplant recipients on kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12(3):443–453

Been-Dahmen J, Grijpma J, Ista E et al (2018) Self-management challenges and support needs among kidney transplant recipients: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 74(10):2393–2405

Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M (2005) Development and testing of a short form of the Patient Activation Measure. Health Serv Res 40(6 Pt 1):1918–1930

NHS England, Public Health England, Monitor, Health Education England, Care Quality Commission, NHS Trust Development Authority. NHS five year forward view. 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2021

Gair RM, Stannard C, Wong E, et al. Transforming participation in chronic kidney disease: programme report. 2019. https://www.thinkkidneys.nhs.uk/ckd/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/01/Transforming-Participation-in-Chronic-Kidney-Disease-1.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2021

Nair D, Cavanaugh KL (2020) Measuring patient activation as part of kidney disease policy: are we there yet? J Am Soc Nephrol 31(7):1435–1443

Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C et al (2010) What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health 25(10):1229–1245

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T et al (2018) Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 52(4):1893–1907

Etikan I, Musa SA, Sunusi RA (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 5:1–4

Hibbard JH, Greene J (2013) What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 32(2):207–214

Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M (2007) Do Increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res 42(4):1443–1463

Lightfoot CJ, Wilkinson TJ, Memory KE, Palmer J, Smith AC (2021) Reliability and validity of the patient activation measure in kidney disease: results of rasch analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16(6):880–888. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.19611220

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Braun V, Clarke V (2019) Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Red Sport Exerc Health 11(4):589–597

Schmid-Mohler G, Schäfer-Keller P, Frei A, Fehr T, Spirig R (2014) A mixed-method study to explore patients’ perspective of self-management tasks in the early phase after kidney transplant. Prog Transplant 24(1):8–18

Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K (2002) Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA 288(19):2469–2475

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol 25(1):54–67

Thomas-Hawkins C, Zazworsky D (2005) Self-management of chronic kidney disease. Am J Nurs 105(10):40–48

Bandura A (1991) Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):248–287

Stanfill A, Bloodworth R, Cashion A (2012) Lessons learned: experiences of gaining weight by kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transpl 22(1):71–78

Weng LC, Dai YT, Huang HL, Chiang YJ (2010) Self-efficacy, self-care behaviours and quality of life of kidney transplant recipients. J Adv Nurs 66(4):828–838

Gordon EJ, Gallant M, Sehgal AR, Conti D, Siminoff L (2009) Medication-taking among adult renal transplant recipients: barriers and strategies. Transpl Int 22(5):534–545

Ruppar TM, Russell CL (2009) Medication adherence in successful kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transpl 19(2):167–172

Low JK, Williams A, Manias E, Crawford K (2014) Interventions to improve medication adherence in adult kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transpl 30(5):752–761

Urstad KH, Wahl AK, Andersen MH, Øyen O, Fagermoen MS (2012) Renal recipients’ educational experiences in the early post-operative phase – a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 26(4):635–642

Hughes J, Wood E, Smith G (2009) Exploring kidney patients’ experiences of receiving individual peer support. Health Expect 12(4):396–406

Gordon EJ, Prohaska TR, Gallant M, Siminoff LA (2009) Self-care strategies and barriers among kidney transplant recipients: a qualitative study. Chronic Illn 5(2):75–91

Schipper K, Abma TA, Koops C, Bakker I, Sanderman R, Schroevers MJ (2014) Sweet and sour after renal transplantation: a qualitative study about the positive and negative consequences of renal transplantation. Br J Health Psychol 19(3):580–591

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 13(2):201–216

Wilkinson TJ, Memory K, Lightfoot CJ, Palmer J, Smith AC (2021) Determinants of patient activation and its association with cardiovascular disease risk in chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study [published online ahead of print April 9, 2021]. Health Expect. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13225

Acknowledgements

This report is independent research funded by the Stoneygate Trust and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC-EM) and supported by the National Institute for Health Research Leicester Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Stoneygate Trust, NHS, National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. We are thankful for the support provided by Jared Palmer during recruitment and data collection for this study. We are grateful to all the participants who took part in the study.

Funding

This work was funded by the Stoneygate Trust and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midland (ARC-EM) and supported by the National Institute for Health Research Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). KEM was supported by a Kidney Research UK Intercalating Student Bursary 2019, made possible by a legacy from the late Professor Robin Eady.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KEM, CJL, TJW, ACS; Methodology—data acquisition: KEM; Data analysis and interpretation: KEM, CJL; Writing—original draft preparation: KEM; Writing—review and editing: KEM, CJL, TJW, ACS; Funding acquisition and study management: ACS; Supervision: CJL, TJW, ACS. All authors have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors gave final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the East Midlands-Leicester South Research Ethics Committee and Health Research Authority (12/EM/0184). The study was undertaken in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Memory, K.E., Wilkinson, T.J., Smith, A.C. et al. A qualitative exploration of the facilitators and barriers to self-management in kidney transplant recipients. J Nephrol 35, 1863–1872 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01325-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01325-w