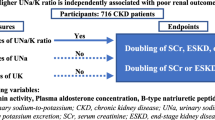

Abstract

Background

Acidosis-induced kidney injury is mediated by the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system, for which urinary renin is a potential marker. Therefore, we hypothesized that sodium bicarbonate supplementation reduces urinary renin excretion in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and metabolic acidosis.

Methods

Patients with CKD stage G4 and plasma bicarbonate 15–24 mmol/l were randomized to receive sodium bicarbonate (3 × 1000 mg/day, ~ 0.5 mEq/kg), sodium chloride (2 × 1,00 mg/day), or no treatment for 4 weeks (n = 15/arm). The effects on urinary renin excretion (primary outcome), other plasma and urine parameters of the renin-angiotensin system, endothelin-1, and proteinuria were analyzed.

Results

Forty-five patients were included (62 ± 15 years, eGFR 21 ± 5 ml/min/1.73m2, plasma bicarbonate 21.7 ± 3.3 mmol/l). Sodium bicarbonate supplementation increased plasma bicarbonate (20.8 to 23.8 mmol/l) and reduced urinary ammonium excretion (15 to 8 mmol/day, both P < 0.05). Furthermore, a trend towards lower plasma aldosterone (291 to 204 ng/L, P = 0.07) and potassium (5.1 to 4.8 mmol/l, P = 0.06) was observed in patients receiving sodium bicarbonate. Sodium bicarbonate did not significantly change the urinary excretion of renin, angiotensinogen, aldosterone, endothelin-1, albumin, or α1-microglobulin. Sodium chloride supplementation reduced plasma renin (166 to 122 ng/L), and increased the urinary excretions of angiotensinogen, albumin, and α1-microglobulin (all P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Despite correction of acidosis and reduction in urinary ammonium excretion, sodium bicarbonate supplementation did not improve urinary markers of the renin-angiotensin system, endothelin-1, or proteinuria. Possible explanations include bicarbonate dose, short treatment time, or the inability of urinary renin to reflect intrarenal renin-angiotensin system activity.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Metabolic acidosis is a common complication in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The prevalence of metabolic acidosis (usually defined as a plasma bicarbonate concentration < 22 mmol/l) increases with higher CKD stage and is 26% and 47% for CKD stages G4 and G5, respectively [1,2]. Metabolic acidosis in CKD is associated with a more rapid progression of CKD [3,4,5]. A recent systematic review showed that metabolic acidosis is a modifiable risk factor for CKD progression as interventions with oral alkali supplementation or an alkaline diet reduce this risk [6]. However, the mechanisms of acidosis-induced kidney injury are incompletely understood.

Current understanding of how acidosis contributes to kidney injury suggests that acid retention triggers an adaptive response to increase ammoniagenesis [7]. This process is orchestrated by activation of the circulating and intrarenal renin-angiotensin systems (RAS) and endothelin-1. However, in a chronic setting and at the single-nephron level, this adaptive response may become maladaptive with the RAS and endothelin-1 contributing to inflammation and fibrosis [8]. For example, it has been shown that locally produced ammonium can activate the complement system with subsequent tubulo-interstitial inflammation and fibrosis [9]. In rats, induction of CKD with 2/3rd nephrectomy causes acid retention and higher levels of angiotensin II and aldosterone in the kidney; alkali treatment reverses these changes [10]. In clinical studies, alkali treatment reduced plasma and urinary aldosterone in patients with CKD stage G2 and G4 [11,12]. Similar findings have been reported for plasma and urinary endothelin-1 [10,13,14,15,16]. However, the activity of the intrarenal RAS is difficult to assess because it is questionable to what degree urinary RAS components truly reflect intrarenal RAS activity [17, 18].

Previous data suggest that the production of angiotensin II in the kidney depends on filtered (i.e., blood-derived) components of the RAS, including renin and angiotensinogen [19,20,21]. Accordingly, the modest alkali-induced lowering of urinary angiotensinogen in patients with CKD stage G3 could suggest reduced intrarenal angiotensin generation [22]. Alternatively, urinary angiotensinogen may simply follow the same urinary excretion pattern as albumin.23 Since this is not the case for urinary renin, [23, 24] this marker may be a more attractive parameter to assess intrarenal RAS activity. Accordingly, we hypothesized that sodium bicarbonate supplementation reduces urinary renin excretion in patients with CKD and metabolic acidosis. To address this, we performed an open-label clinical trial in which patients were randomized to receive sodium bicarbonate or sodium chloride, or served as time-controls. In addition to the measurement of plasma and urinary RAS parameters, we also analyzed the effects on urinary endothelin-1, albumin, α1-microglobulin, and complement.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an open-label randomized controlled trial at 4 study sites in The Netherlands, including Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Amsterdam University Medical Centers. University Medical Center Groningen and Leiden University Medical Center. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center (MEC-2013–332). The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov with registration number NCT02896309. Patients were recruited from outpatient nephrology clinics between April 2014 and December 2018. All patients with CKD stage G4 (eGFR 15–30 ml/min/1.73m2) and with plasma bicarbonate levels between 15.0 and 24.0 mmol/l were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were sodium bicarbonate use in the month preceding the study, heart failure New York Heart Association class 3 or 4, liver cirrhosis with ascites and the inability to withdraw diuretics, systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg despite the use of three different antihypertensive drugs, kidney transplantation, and use of calcineurin inhibitors. Patients were randomized for 4-week treatment with sodium bicarbonate (3 × 1000 mg/day, providing a sodium load of 36 mmol per day), sodium chloride (2 × 1000 mg/day, providing a sodium load of 34 mmol per day) or no treatment (time control). Allocation to treatment was done by randomization using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. Stratified randomization was used to ensure that a similar number of patients were allocated to each intervention at the different study sites.

Measurements

At baseline and after 2 and 4 weeks, blood and 24-h urine samples were collected and office blood pressure was measured. Plasma and urine electrolytes, albumin, creatinine, and α1-microglobulin were measured at the Department of Clinical Chemistry of the Erasmus Medical Center. Venous blood gas analysis was performed directly after sample collection on a blood gas analyzer (ABL90 Flex Plus, Radiometer, The Netherlands; RAPIDLab 1265, Siemens, Germany). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation [25]. Creatinine clearance was calculated based on plasma and urinary creatinine excretion. Urinary ammonium was measured using the Berthelot-method, as described previously [26]. Plasma renin was measured using a radioimmunometric assay (Cisbio, Saclay, France). Urinary renin was measured using an in-house enzyme-kinetic assay that quantifies angiotensin I generation in the presence of excess sheep angiotensinogen [27]. In order to convert angiotensin I-generating activity to renin concentration, a conversion factor was used based on the fact that 1 ng Ang I/mL per hour corresponds to 2.6 pg renin/mL. Urinary angiotensinogen was measured as the maximum quantity of Ang I that was generated during incubation with excess recombinant renin using the same in-house assay [27]. Plasma and urinary aldosterone were measured by radioimmunoassay (Demeditec, Kiel, Germany). Endothelin-1 was measured using a Quantikine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R&D systems, Minneapolis, USA). Urine soluble terminal complement complex sC5b-9 was measured by ELISA as previously described [28]. All urinary excretions were expressed as ratio with urine creatinine to correct for any incomplete collections, as reported previously [29].

Statistics

Data are presented as frequencies (percentages), mean ± standard deviation and median with 10th–90th percentile, as appropriate. The primary outcome was the change in urinary renin-to-creatinine ratio. A power calculation based on previous data indicated that a minimum of 45 patients (15 per treatment arm) was required to show that sodium bicarbonate supplementation would reduce urinary renin excretion by 0.3 ng/L (α = 0.025, β = 0.8, standard error 0.26) [23]. Secondary outcomes included the urinary-to-creatinine ratios of angiotensinogen, endothelin-1, albumin and α1-microglobulin. An exploratory analysis was performed for the treatment effects on kidney function, blood pressure and plasma potassium. The omnibus K2 test was used to test for normality. Non-normally distributed data were log-transformed for statistical analysis. Primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed using mixed linear models that included treatment and period (time) as fixed effects. In case a significant interaction between treatment and period was found, post-hoc tests were performed with correction for multiple comparisons according to Dunnett. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics (IBM, version 24.0). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Forty-seven patients entered the study protocol, of whom two patients discontinued treatment due to adverse reactions to sodium chloride supplementation (1 patient with gastrointestinal symptoms, 1 patient with polydipsia). Forty-five patients completed the study protocol (15 patients/arm). All patients that finished the treatment period were included in the analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes. The average age was 62 ± 15 years, 78% were males, the average eGFR was 21 ± 15 ml/min/1.73 m2, and the average plasma bicarbonate was 21.7 ± 3.3 mmol/l (Table 1).

Effects on acid–base status and the renin-angiotensin system

Sodium bicarbonate supplementation increased plasma bicarbonate (with 3.0 ± 0.7 and 2.9 ± 0.8 mmol/L after 2 and 4 weeks of treatment, respectively; P < 0.01 versus baseline) and lowered urinary ammonium excretion (with − 7.0 ± 1.5 mmol/day and − 3.6 ± 1.9 mmol/day, P < 0.05 versus baseline, Fig. 1). No significant changes in plasma bicarbonate or urinary ammonium excretion occurred with sodium chloride supplementation and without treatment. Sodium chloride but not sodium bicarbonate supplementation significantly reduced plasma renin (with − 9.5 and − 7.9 ng/L, P < 0.05 versus baseline, Fig. 1). A trend towards a reduction in plasma aldosterone was observed with sodium bicarbonate supplementation after 4 weeks (− 99 ng/L, P = 0.07). No changes in the aldosterone-to-renin ratio were observed with either treatment (data not shown).

Sodium bicarbonate increased plasma bicarbonate and urinary sodium excretion and lowered urinary ammonium excretion, whereas sodium chloride treatment only increased urinary sodium excretion after 2 weeks of treatment. The horizontal black lines represent the median value; the lower and upper boundaries of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles; the whiskers represent the lowest and highest values. HCO3− bicarbonate, K+ potassium, Na+, sodium, NaCl sodium chloride, NH4+ ammonium, NaHCO3 sodium bicarbonate. *P < 0.05 for the within-group difference from baseline. †P = 0.07 for the within-group difference versus baseline; #P < 0.05 for the difference versus control

Primary and secondary outcomes

In all three treatment groups, no significant within-group differences were detected in the urinary renin-to-creatinine ratio after two or four weeks of treatment (Table 2). In addition, no between-group differences were found. Similarly, sodium bicarbonate supplementation had no significant effect on any of the secondary outcome parameters (Table 2). In the within-group comparison, sodium chloride supplementation increased urinary angiotensinogen, albumin, and α1-microglobulin excretion; no between-group differences were shown for these outcomes (Table 2). Five patients did not use RAS-inhibitors. Two of these patients received sodium bicarbonate and this reduced urinary aldosterone (65% and 39% reduction after 2 and 4 weeks), an effect that was not observed with the other interventions. No effects on the other outcome parameters was observed. In addition, no differences were observed in a sensitivity analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes between patients with CKD stage G4a (eGFR 29–23 mL/min per 1.73 m2) and G4b (eGFR 22–16 mL/min per 1.73 m2). To determine whether correction of metabolic acidosis reduced the activity of the complement system, we also measured soluble terminal complement complex sC5b-9 in urine at the end of treatment. Urine sC5b-9 was undetectable in forty patients (< 0.05 U/ml). Of the five patients with detectable urinary complement, three had albuminuria > 1 g/day.

Effects on kidney function, blood pressure and plasma potassium

Sodium bicarbonate or sodium chloride supplementation did not lead to significant changes in eGFR (Table 3). However, sodium bicarbonate did cause a small but statistically significant increase in urinary creatinine excretion after 4 weeks, which was not observed with sodium chloride treatment. No significant differences were identified for systolic and diastolic blood pressure within or between groups. After 4 weeks, there was a trend towards a reduction in plasma potassium with sodium bicarbonate (P = 0.06 for difference baseline versus 4 weeks), which was not observed with sodium chloride and without treatment.

Discussion

In this open-label, three-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) we investigated whether sodium bicarbonate supplementation in patients with CKD and metabolic acidosis lowers urinary renin, as a potential measure of the intrarenal RAS. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation corrected metabolic acidosis and lowered urinary ammonium excretion. Despite these effects, we observed no within- or between-group differences for urinary renin. In addition, sodium bicarbonate had no significant effect on the urinary excretion of angiotensinogen, aldosterone, endothelin-1, albumin, or α1-microglobulin. Despite these negative findings, we believe our study adds three relevant aspects to the evolving field of metabolic acidosis in CKD.

First, several other clinical trials with sodium bicarbonate supplementation were also unable to show an effect on their primary endpoints. In this regard, our study is most comparable to the recent study by Raphael and colleagues who investigated the effect of sodium bicarbonate on urinary kidney injury markers [29]. In their placebo-controlled, double-blind RCT sodium bicarbonate was supplemented for six months at a dose of 0.5 mEq/kg to patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and an eGFR between 15 and 89 ml/min/1.73m2. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation increased plasma bicarbonate and reduced urinary ammonium, but did not reduce urinary TGF-β1, KIM-1, fibronectin, NGAL, or albumin. The most likely explanation for a lack of effect is that the dose of sodium bicarbonate was too low. Indeed, most RCTs that were unable to show an effect on the primary endpoint used a dose of 0.3–0.5 mEq/kg [29,30,−31], whereas positive RCTs used a higher dose of approximately 1.0 mEq/kg [11,16,32]. To address this issue, Raphael et al. recently published a dose-finding study confirming that a higher dose of sodium bicarbonate (0.8 mEq/kg) had a stronger effect on plasma bicarbonate and urinary ammonium compared with a lower dose (0.5 mEq/kg). Wesson et al. showed that 0.5 mEq/kg sodium bicarbonate supplementation for 30 days did reduce plasma aldosterone and endothelin-1 levels in patients with CKD stage G1 or G2.[12] In agreement, we also observed that sodium bicarbonate reduced plasma aldosterone, although this was of borderline significance. The effect of sodium bicarbonate on aldosterone may be mediated by lowering of plasma potassium, although this was also of borderline significance in our study. In the RCT by Melamed et al. sodium bicarbonate supplementation also increased plasma bicarbonate and reduced plasma potassium [30]. In contrast, three previous studies did find effects of a lower sodium bicarbonate dose (0.3 or 0.5 mEq/kg) on urinary aldosterone, endothelin-1, angiotensinogen, albumin, and NAG, although the effect sizes were modest [12,15,16]. Possible explanations for the discrepancy with our study is that previous studies applied a longer treatment time (up to five years) and included patients with earlier stages of CKD. Finally, the use of RAS-inhibitors (used by 88% of the patients in this study) may suppress the RAS to an extent that alkali has no further effect.

A second issue that is raised by our study is whether urinary renin can truly be considered a marker of the intrarenal RAS. Determinants of urinary renin excretion include glomerular filtration, proximal tubular reabsorption, local production in the collecting duct, and intratubular conversion of plasma-derived prorenin to renin. In a study including 101 patients with or without diabetes mellitus and hypertension, urinary renin did not correlate with plasma renin and especially dissociated in patients with diabetes mellitus or on RAS-inhibitors. Accordingly, we proposed urinary renin to be a marker for the intrarenal RAS [33,34]. In a subsequent study, however, we showed that the glomerular sieving coefficient for renin is higher than for albumin and that variation in proximal tubular reabsorption explains the different urinary excretion patterns of renin and albumin [34]. We also showed that urinary renin does not reflect converted prorenin. A recent study in mice and humans with diabetes confirmed these concepts and did not find evidence for local production of renin [35]. Together these recent insights suggest that urinary renin excretion is mainly determined by variation in glomerular filtration and proximal tubular reabsorption and is therefore not a good marker for the intrarenal RAS. It would be of interest to explore whether renin mRNA or protein in urinary extracellular vesicles – which are mainly derived from tubular epithelial cells – is a better read-out of intrarenal RAS [36]. This also implies that positive effects of oral alkali may have been obscured by counteracting effects of the sodium load on filtration or reabsorption. We recently showed that an acid load increases albuminuria [37]. Therefore, correction of acidosis would be expected to reduce albuminuria, unless this effect is counterbalanced, for example by the sodium load. This could also explain why fruits and vegetables have more positive effects than sodium bicarbonate [38]. In this regard it would be interesting to assess the effect of oral alkali given with another cation. A clinical trial that compares the effects of potassium citrate with potassium chloride and placebo on kidney outcomes in CKD stage G3b and G4 is currently ongoing and may provide more insight into this matter [39.]

A third relevant finding in our study is that sodium chloride but not sodium bicarbonate increased albuminuria. This is relevant, because the dose-finding study by Raphael et al. observed an increase in albuminuria with the high dose (i.e., 0.8 mEq/kg per day) but not with the low dose (i.e., 0.5 mEq/kg per day) sodium bicarbonate [40]. The effect of alkali treatment on albuminuria is most likely the result of hemodynamic changes due to the sodium load given with bicarbonate. Another possibility is that a higher urine pH resulted in the detection of more intact albumin in the assay [41]. However, the results in our study and previous studies showing that sodium bicarbonate in both high and low doses also lowers albuminuria [11,15,22] suggest that assay characteristics do not fully explain the reported changes in albuminuria.

This is the first study to analyze the effect of sodium bicarbonate on urinary renin excretion. Another strength of this study is the inclusion of two control groups. However, this study also has a number of limitations. As discussed above, the dose of sodium bicarbonate or treatment time may explain why previously observed effects on aldosterone, endothelin-1, and proteinuria were not observed in this study. Although sample size was also modest, we recently showed in a study with a similar sample size that an acute acid load caused significant differences in urinary renin excretion between healthy subjects and patients with CKD [37]. Again, these results suggested that glomerular hyperfiltration or reduced proximal tubular reabsorption caused these changes in urinary renin. Therefore, the lack of effect of sodium bicarbonate supplementation on urinary renin likely means that no net changes in filtration or reabsorption occurred.

In conclusion, despite correction of acidosis and reduction in urinary ammonium excretion, sodium bicarbonate supplementation did not improve urinary markers of the renin-angiotensin system, endothelin-1, or proteinuria. Explanations for the lack of effect include bicarbonate dose, treatment time, or the inability of urinary renin to reflect intrarenal renin-angiotensin system activity.

References

Kim HJ, Kang E, Ryu H, Han M, Lee KB, Kim YS, Sung S, Ahn C, Oh KH (2019) Metabolic acidosis is associated with pulse wave velocity in chronic kidney disease: Results from the KNOW-CKD Study. Sci Rep 9:16139

Moranne O, Froissart M, Rossert J, Gauci C, Boffa JJ, Haymann JP, M’Rad M B, Jacquot C, Houillier P, Stengel B, Fouqueray B and NephroTest Study G (2009) Timing of onset of CKD-related metabolic complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:164–171

Madias NE. Metabolic Acidosis and CKD Progression. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020.

Raphael KL, Carroll DJ, Murray J, Greene T, Beddhu S (2017) Urine Ammonium Predicts Clinical Outcomes in Hypertensive Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 28:2483–2490

Dobre M, Yang W, Chen J, Drawz P, Hamm LL, Horwitz E, Hostetter T, Jaar B, Lora CM, Nessel L, Ojo A, Scialla J, Steigerwalt S, Teal V, Wolf M, Rahman M, Investigators C (2013) Association of serum bicarbonate with risk of renal and cardiovascular outcomes in CKD: a report from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis 62:670–678

Navaneethan SD, Shao J, Buysse J, Bushinsky DA (2019) Effects of Treatment of Metabolic Acidosis in CKD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14:1011–1020

Wesson DE, Buysse JM, Bushinsky DA (2020) Mechanisms of Metabolic Acidosis-Induced Kidney Injury in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 31:469–482

Loniewski I, Wesson DE (2014) Bicarbonate therapy for prevention of chronic kidney disease progression. Kidney Int 85:529–535

Nath KA, Hostetter MK and Hostetter TH. Pathophysiology of chronic tubulo-interstitial disease in rats. Interactions of dietary acid load, ammonia, and complement component C3. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:667–75.

Wesson DE, Simoni J (2010) Acid retention during kidney failure induces endothelin and aldosterone production which lead to progressive GFR decline, a situation ameliorated by alkali diet. Kidney Int 78:1128–1135

Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE (2013) A comparison of treating metabolic acidosis in CKD stage 4 hypertensive kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or sodium bicarbonate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8:371–381

Wesson DE, Simoni J, Broglio K, Sheather S (2011) Acid retention accompanies reduced GFR in humans and increases plasma levels of endothelin and aldosterone. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300:F830–F837

Phisitkul S, Hacker C, Simoni J, Tran RM, Wesson DE (2008) Dietary protein causes a decline in the glomerular filtration rate of the remnant kidney mediated by metabolic acidosis and endothelin receptors. Kidney Int 73:192–199

Wesson DE, Jo CH, Simoni J (2012) Angiotensin II receptors mediate increased distal nephron acidification caused by acid retention. Kidney Int 82:1184–1194

Mahajan A, Simoni J, Sheather SJ, Broglio KR, Rajab MH, Wesson DE (2010) Daily oral sodium bicarbonate preserves glomerular filtration rate by slowing its decline in early hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int 78:303–309

Phisitkul S, Khanna A, Simoni J, Broglio K, Sheather S, Rajab MH, Wesson DE (2010) Amelioration of metabolic acidosis in patients with low GFR reduced kidney endothelin production and kidney injury, and better preserved GFR. Kidney Int 77:617–623

Sun Y, Goes Martini A, Janssen MJ, Garrelds IM, Masereeuw R, Lu X, Danser AHJ (2020) Megalin: A Novel Endocytic Receptor for Prorenin and Renin. Hypertension 75:1242–1250

Sun Y, Bovee DM, Danser AHJ (2019) Tubular (Pro)renin Release. Hypertension 74:26–28

Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Janjoulia T, Fletcher NK, Giani JF, Nguyen MT, Riquier-Brison AD, Seth DM, Fuchs S, Eladari D, Picard N, Bachmann S, Delpire E, Peti-Peterdi J, Navar LG, Bernstein KE, McDonough AA (2013) The absence of intrarenal ACE protects against hypertension. J Clin Invest 123:2011–2023

van Kats JP, Schalekamp MA, Verdouw PD, Duncker DJ, Danser AH (2001) Intrarenal angiotensin II: interstitial and cellular levels and site of production. Kidney Int 60:2311–2317

Seikaly MG, Arant BS Jr, Seney FD Jr (1990) Endogenous angiotensin concentrations in specific intrarenal fluid compartments of the rat. J Clin Invest 86:1352–1357

Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE (2014) Treatment of metabolic acidosis in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or oral bicarbonate reduces urine angiotensinogen and preserves glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int 86:1031–1038

van den Heuvel M, Batenburg WW, Jainandunsing S, Garrelds IM, van Gool JM, Feelders RA, van den Meiracker AH, Danser AH (2011) Urinary renin, but not angiotensinogen or aldosterone, reflects the renal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activity and the efficacy of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade in the kidney. J Hypertens 29:2147–2155

Roksnoer LC, Verdonk K, van den Meiracker AH, Hoorn EJ, Zietse R, Danser AH (2013) Urinary markers of intrarenal renin-angiotensin system activity in vivo. Curr Hypertens Rep 15:81–88

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, Ckd EPI (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150:604–612

Cunarro JA, Weiner MW (1974) A comparison of methods for measuring urinary ammonium. Kidney Int 5:303–305

de Lannoy LM, Danser AH, van Kats JP, Schoemaker RG, Saxena PR, Schalekamp MA (1997) Renin-angiotensin system components in the interstitial fluid of the isolated perfused rat heart. Local production of angiotensin I Hypertension 29:1240–1251

Mollnes TE, Lea T, Froland SS, Harboe M (1985) Quantification of the terminal complement complex in human plasma by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on monoclonal antibodies against a neoantigen of the complex. Scand J Immunol 22:197–202

Raphael KL, Greene T, Wei G, Bullshoe T, Tuttle K, Cheung AK, Beddhu S (2020) Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation and Urinary TGF-beta1 in Nonacidotic Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15:200–208

Melamed ML, Horwitz EJ, Dobre MA, Abramowitz MK, Zhang L, Lo Y, Mitch WE, Hostetter TH (2020) Effects of Sodium Bicarbonate in CKD Stages 3 and 4: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Clinical Trial. Am J Kidney Dis 75:225–234

Csg Bi (2020) Clinical and cost-effectiveness of oral sodium bicarbonate therapy for older patients with chronic kidney disease and low-grade acidosis (BiCARB): a pragmatic randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med 18:91

Di Iorio BR, Bellasi A, Raphael KL, Santoro D, Aucella F, Garofano L, Ceccarelli M, Di Lullo L, Capolongo G, Di Iorio M, Guastaferro P, Capasso G and Group UBIS (2019) Treatment of metabolic acidosis with sodium bicarbonate delays progression of chronic kidney disease: the UBI Study. J Nephrol 32:989–1001

Persson F, Lu X, Rossing P, Garrelds IM, Danser AH, Parving HH (2013) Urinary renin and angiotensinogen in type 2 diabetes: added value beyond urinary albumin? J Hypertens 31:1646–1652

Roksnoer LC, Heijnen BF, Nakano D, Peti-Peterdi J, Walsh SB, Garrelds IM, van Gool JM, Zietse R, Struijker-Boudier HA, Hoorn EJ, Danser AH (2016) On the Origin of Urinary Renin: A Translational Approach. Hypertension 67:927–933

Tang J, Wysocki J, Ye M, Valles PG, Rein J, Shirazi M, Bader M, Gomez RA, Sequeira-Lopez MS, Afkarian M, Batlle D (2019) Urinary Renin in Patients and Mice With Diabetic Kidney Disease. Hypertension 74:83–94

Qi Y, Wang X, Rose KL, MacDonald WH, Zhang B, Schey KL, Luther JM (2016) Activation of the Endogenous Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System or Aldosterone Administration Increases Urinary Exosomal Sodium Channel Excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 27:646–656

Bovee DM, Janssen JW, Zietse R, AH JD and Hoorn EJ. Acute acid load in chronic kidney disease increases plasma potassium, plasma aldosterone and urinary renin. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1821–1823.

Goraya N, Munoz-Maldonado Y, Simoni J, Wesson DE (2019) Fruit and Vegetable Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Related Metabolic Acidosis Reduces Cardiovascular Risk Better than Sodium Bicarbonate. Am J Nephrol 49:438–448

Gritter M, Vogt L, Yeung SMH, Wouda RD, Ramakers CRB, de Borst MH, Rotmans JI, Hoorn EJ (2018) Rationale and Design of a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial Assessing the Renoprotective Effects of Potassium Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron 140:48–57

Raphael KL, Isakova T, Ix JH, Raj DS, Wolf M, Fried LF, Gassman JJ, Kendrick C, Larive B, Flessner MF, Mendley SR, Hostetter TH, Block GA, Li P, Middleton JP, Sprague SM, Wesson DE, Cheung AK (2020) A Randomized Trial Comparing the Safety, Adherence, and Pharmacodynamics Profiles of Two Doses of Sodium Bicarbonate in CKD: the BASE Pilot Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 31:161–174

Kania K, Byrnes EA, Beilby JP, Webb SA, Strong KJ (2010) Urinary proteases degrade albumin: implications for measurement of albuminuria in stored samples. Ann Clin Biochem 47:151–157

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients who participated in this trial, our colleagues who helped with the inclusion of patients, the research physicians and nurses who helped with data collection (E.F.E. Wenstedt, M.A. De Jong, B.M. Voorzaat, B. Nome and N. Scheper-Van den Berg). This study was organized as part of the Dutch NOVO platform and was funded by a research grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation (14OK19 to EJH).

Funding

Dutch Kidney Foundation (14OK19 to EJH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center (MEC-2013-332).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bovée, D.M., Roksnoer, L.C.W., van Kooten, C. et al. Effect of sodium bicarbonate supplementation on the renin-angiotensin system in patients with chronic kidney disease and acidosis: a randomized clinical trial. J Nephrol 34, 1737–1745 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-020-00944-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-020-00944-5