Abstract

Supervision is paramount within applied behavior analysis. This is particularly true in the case of Board Certified Behavior Analysts® (BCBAs®) and trainees (i.e., those accruing hours and experience to become BCBAs). Given the importance of supervision in shaping future BCBAs (and subsequently the field of applied behavior analysis), researchers have emphasized supervision practices as they relate to BCBAs and trainees. However, what type of work is occurring in this area, such as empirical intervention studies or provision of supervisory recommendations through discussion-style articles, needs to be clarified. Therefore, we conducted the first and most comprehensive systematic review of supervision research related to BCBAs and trainees. Results indicated that most of the articles and work pertaining to BCBA supervision are discussion-style articles, with several survey studies and few empirical intervention studies. We discuss implications and areas for future supervision research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Supervision is essential within the practice of applied behavior analysis, and the importance of supervision has perhaps never been more apparent (cf. LeBlanc, Sellers et al., 2020). Supervision serves to monitor supervisee-clients’ progress (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], n.d., 2020; LeBlanc & Luiselli, 2016). Perhaps more important, supervision also serves as an impetus for creating future high-quality, ethical, and clinically sound supervisors (BACB, 2020; Brodhead & Higbee, 2012; Hartley et al., 2016). That is, through supervision, supervisors are responsible for equipping their trainees with well-rounded skillsets in areas such as service delivery; collaboration; and continued professional development and career sustainment (i.e., prevention of burnout), which ultimately affects client outcomes and representation of the field at-large (Kranak, 2022; LeBlanc, Taylor et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2022). In this sense, supervision serves as a primary mechanism of quality assurance and gatekeeping for applied behavior-analytic service delivery, as it (hopefully) develops well-qualified individuals to provide both future supervision and clinical services (Carr & Nosik, 2017; Silbaugh & El Fattal, 2022; Weiss & Shook, 2010). The critical role that supervision plays in developing future supervisors and clinicians is further emphasized when considering that improper supervision is the most reported ethical violation received by the BACB (2018a).

The BACB (n.d.) broadly defines supervision as the provision of oversight by a BCBA of individuals who are accruing fieldwork hours to become certified (e.g., traineesFootnote 1) and individuals who are providing behavior-analytic services (e.g., behavior technicians). Along with the demand for BCBAs, the number of individuals requiring supervision (e.g., behavior technicians, trainees) is at an all-time high (Andzik & Kranak, 2021; BACB, 2021). As such, the supervisory demand for BCBAs has never been greater. It is particularly true as BCBAs must now wait one year postcertification before providing supervision to trainees unless they are supervised by a qualified supervisor (BACB, 2018a). This new 1-year postcertification requirement creates additional supervisory demand by limiting the number of individuals who can independently provide supervision and increasing the number of individuals who require supervision (i.e., BCBAs providing supervision with less than 1 year of certification). Thus, there is a need to develop and improve supervisory practices for and of BCBAs to meet the supervisory demand effectively and efficiently. Fortunately, authors have recently emphasized supervision as it relates to BCBAs (e.g., Sellers, Ala'i-Rosales et al., 2016a).

One particular area of supervision that has received significant attention is supervision practices of BCBAsFootnote 2 as they relate to trainees. For example, Valentino et al. (2016) described the benefits of and provided recommendations (e.g., using peer feedback, providing presentation opportunities) for implementing effective group supervision with trainees. Likewise, both Sellers, Valentino et al. (2016) and Helvey et al. (2022) discussed considerations for individual supervision, with the former focusing on considerations for supervisors and the latter on considerations for supervisees (e.g., trainees). Finally, Sellers et al. (2019) conducted the most extensive survey to date of supervision practices of BCBAs. Sellers et al. (2019) identified areas of strength and success of supervisors (e.g., using contracts, setting clear expectations), as well as areas for growth (e.g., evaluating supervisory relationships, using competency-based evaluations). They provided recommendations for how supervisors might improve their supervisory repertoire.

Although researchers have placed an increased emphasis on the supervision practices of BCBAs, it is unknown precisely what work is occurring in this area. Put another way, it is unclear to what extent the work related to the supervision practices of BCBAs is comprised of discussion-based and recommendation-style articles (e.g., Britton et al., 2021), surveys (e.g., DiGennaro Reed & Henley, 2015), experimental evaluations (e.g., Carroll et al., 2022), or supervision tools and whether those tools have been empirically validated (e.g., Garza et al., 2018). There has not been a comprehensive review of supervision research and practices as they relate to BCBAs. Given the remarkable growth of publications on supervision since the Behavior Analysis in Practice supervision special section (i.e., Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4); LeBlanc & Luiselli, 2016), a systematic review is sorely needed to organize and summarize the content for practitioners and researchers. Such a review is needed to critically appraise the work related to supervision and identify gaps and areas for improvement (Gopalakrishnan & Ganeshkumar, 2013; Munn et al., 2018).

We sought to summarize the overall state of the literature as well as guide and provide recommendations for future research in this area. Thus, the purpose of this review was to answer the following research questions:

-

1)

What are researchers studying and ultimately disseminating regarding BCBA supervision?

-

2)

Who is conducting this work and publishing in this area of behavior-analytic supervision?

-

3)

What are the prevalence and type of article (e.g., experimental evaluation, discussion-style article), general themes and focus of each article, methods employed, and recommendations shared?

Method

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement when conducting this review (Page et al., 2021). We used multiple search strategies, which were initiated and completed in February 2022, and then updated in December 2022. First, we used the EBSCO platform to search the ERIC database with the search string: (supervision or supervising or supervisory or supervisor) AND ("board certified behavior analyst" OR "BCBA"). Second, we used the OVID platform to search Academic Search Complete, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Medline First with the input parameters of: (practicum supervision OR professional supervision OR supervision) AND (behavior analysis OR board certified behavior analyst OR applied behavior analysis).

We included articles that met the following criteria: (1) the article was an experimental evaluation of an intervention to modify behavior related to supervision; (2) the article was a qualitative and/or survey-based inquiry with participants/respondents being asked questions about their supervision experience as a BCBA/doctoral-level BCBA (i.e., BCBA-D) supervisor or trainee receiving supervision; (3) behavior-analytic supervision accounted for more than 50% of the article's analysis or overall discussionFootnote 3; and (4) the article was published (including online early view) in a peer-reviewed journal or a completed thesis or dissertation. Given the lacking experimental studies published in this area, we opted to include unpublished works (see Hartling et al., 2017). We excluded articles if they: (1) were published updates to a previously published article (e.g., "Corrections to," "Revisions to," corrigenda or errata); (2) were book reviews or book chapters; (3) were focused on BCBAs providing supervision to nontrainee staff (e.g., teachers or paraprofessionals not accruing hours towards certification); (4) were "Comments," "In Response Tos," or "Ask the Editors;" (5) were literature reviews; (6) were published before BACB supervision standards were in place; or (7) were not available in English or published or made available after December 1, 2022.

The initial electronic search yielded 394 results and were imported into Zotero (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, 2022). See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flowchart outlining these search procedures. Thirty-five duplicates were removed. The first and second authors (both BCBA-Ds) conducted a title, abstract, and full-review text of the remaining 359 articles using the outlined inclusion and exclusion criteria. We ensured the reliability of this screening by overlapping across 41% (146/359) of articles which resulted in 98% agreement. To avoid inadvertently excluding an article at the screening phase that required a full-text review for consideration, all articles not in agreement were moved forward to full-text review. We retained 38 articles for full-text review after removing 321 articles following the title and abstract review. Then, we conducted a hand search of the entire journal (i.e., Behavior Analysis in Practice) that accounted for the most identified articles. This hand search resulted in the identification of 1 additional article for a total of 39 articles for full-text review.

After a full-text review of the remaining 39 articles, we retained 25 and excluded 14. Among those excluded, four articles were unrelated to supervision, three focused exclusively on licensure, two were repeated citations, two were published before behavior-analytic supervision standards were in place, two had no focus on BCBA-related supervision, and one was a literature review. At this phase, we calculated interrater agreement for 30% of articles included for full-text review; the agreement was 92%. Only one disagreement occurred, and it was rejected and removed after discussion. Then, we conducted an ancestral search of each reference list from the 25 articles and each publication that cited one of the 25 articles. We identified seven additional articles during the ancestral search. At this point, the first and second authors double reviewed all of the additional seven articles and came to a 100% agreement to include each of them (five from the forward search, two from the backward search). We conducted another ancestral search on the newly included seven articles and identified one additional article via the backward search. We then completed a final hand search of Behavior Analysis in Practice on December 1, 2022 to identify potentially relevant articles published since the initial search. Seven additional articles were identified. In total, 40 articles were included in our analysis. Because books were not a focal point of this review, they were not included in the analysis. However, readers (especially those working in higher education interested in texts for courses) could benefit from knowing what supervision books are currently available. We identified 10 books related to BCBA supervision and trainees through our search procedures and they are listed in the Appendix.

Data Extraction and Analysis

We first coded each article based on its type. That is, we classified each article as either an intervention study, a survey-based study, mixed-method study, or a discussion-style article. Intervention studies were defined as any article that included an independent and dependent variable focused on changing behavior related to BCBA supervisory practices (i.e., an experimental evaluation). A survey-based study included a quantitative analysis of responses following the dissemination of a survey to seek opinions of participants/respondents related to BCBA supervisory practices. Mixed-method papers included components of more than one of the following evaluation strategies: survey, interview, and case study. Discussion-style articles were articles published without a participant pool or manipulated variables. Instead, the authors of discussion-style articles focused on disseminating information about a BCBA supervision topic as it related to previously published literature or their experience. This type of article varied from a literature review with the primary focus of not sharing what has been written, but providing recommendations to the field around BCBA supervision practices.

Coding for All Articles

Every included article was coded for: (1) article type as described above; (2) publication outlet (i.e., peer-reviewed journal or thesis/dissertation); (3) the central theme related to supervision (e.g., group or individual supervision, training recommendations); (4) the number of articles that cited the article being coded; and (5) if the article included a takeaway tool (e.g., task analysis for a training procedure, job aid). In addition, we coded the total number of included articles published in each journal in which an included article appeared. We also coded all authors of the included articles and the number of times a given author appeared as a first or nonfirst author. Two authors coded each article, and 100% agreement between codes was reached.

Coding for Intervention Studies

For each article coded as an intervention study, we further coded the following variables: (1) number and description of participants (e.g., BCBAs, trainees); (2) independent variables(s); (3) dependent variable(s); (4) experimental design (i.e., single-case experimental design [SCED], group design, or case study); (5) type of SCED (e.g., reversal) if an SCED was used; (6) results reported by authors; (7) social validity across goals, procedures, and outcomes; and (8) presence of measures of maintenance and/or generalization.

Coding for Survey-Based and Mixed-Method Studies

For each article coded as a survey-based or mixed-method study, we further coded the following variables: (1) number and description of respondents (or participants in the mixed-methods study); (2) inclusion criteria; (3) research question(s); (4) statistical analyses beyond descriptive statistics; and (5) findings as reported by the authors.

Coding for Discussion-Style Articles

For each article coded as a discussion-style article, we further coded the following variables: (1) aim(s) of the article and (2) description(s) of any provided takeaway tools.

Results

All Articles

As mentioned, 40 articles were retained and included in our analysis. Table 1 contains the general characteristics of all included articles. Within Table 1, articles are organized by publishing outlet (i.e., published or unpublished). Within each publishing outlet, articles are further organized by theme. Of those 40 articles, 50% (20/40) were discussion-style articles; 25% (10/40) were survey-based studies, with one mixed-methods study; and 25% (10/40) were intervention studies. Seventy-eight percent (31/40) were published articles and 22% (9/40) were unpublished theses/dissertations. It is interesting that unpublished theses/dissertations accounted for 70% (7/10) of all intervention studies. Only three intervention studies were published articles (i.e., Atkinson et al., 2022; Carroll et al., 2022; Parry-Cruwys et al., 2022).

We identified and coded the following seven main themes present in articles: (1) improving skillsets and supervisory experiences of trainees (33%, 13/40); (2) general recommendations for BCBAs providing supervision (13%, 5/40); (3) ethics (8%, 3/40); (4) feedback (7%, 3/40); (5) diversity, equity, and inclusion and cultural humility and competence (7%, 3/40); (6) meeting skills and behaviors (5%, 2/40); (7) soft skills (5%, 2/40); and (8) recommendations for virtual supervision or COVID-19-specific considerations (5%, 2/40). Seven articles (17%) did not fit neatly into the themes but focused on various topics such as staff performance or supervisory relationship satisfaction.

Articles were published, or dissertations were defended between 2002 and 2022. Eight articles were published both in 2021 and 2022, seven in 2016, six in 2019, and five in 2020. Figure 2 depicts the cumulative number of all articles published per year (top panel) and cumulative number of all articles based on article type published per year (bottom panel) The most-cited article (i.e., DiGennaro Reed & Henley, 2015) was cited 93 times (per Google Scholar); the median number of times an article was cited was 17 (range: 0–93).

Articles Published per Year. Note. The top panel depicts all articles published (or dissertations defended) per year within one data path. The bottom panel depicts all discussion-style, survey-based, or intervention studies published (or defended) per year. 2018 includes one mixed-method study included in surveys

Bibliometric Analyses

Regarding which outlets these articles appeared, Behavior Analysis in Practice contained 68% (27/40) of the articles. The Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, Behavior Modification, and the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health contained 2.5% (1/40 each) articles. The remaining 22% (9/40) were unpublished dissertations. Seventy-eight different authors contributed to this research base. Seven authors published more than one article; the remaining 71 authors each appeared in one article. The top contributing authors were: (1–2) Linda LeBlanc (total n = 6, first-author n = 3) and Tyra Sellers (total n = 6, first-author n = 4), and (3) Amber Valentino (total n = 4, first-author n = 1). Notably, the top three authors accounted for nearly half of all publications related to supervision (i.e., 40%, 16/40). The remaining list is available from the corresponding author.

Intervention Studies

Table 2 contains the data and coded variables related to intervention studies. Across 10 articles and 11 completed studies,Footnote 4 88 participants were included (Mdn = 8; range: 3–22). These participants included supervisors (i.e., BCBAs or BCBA-Ds; 38%, 33/88) and trainees (62%, 55/88). Five studies included behavioral skills training as the independent variable. Two studies used an online self-paced program, and one study each used public posting and praise statements, video modeling with voice-over, and a newly designed structured supervision tool. The dependent variable in all studies was the fidelity of implementing target skills (e.g., providing feedback, culturally responsive verbal behavior). All authors used SCEDs. Researchers used a multiple baseline design in nine articles; Yakich (2020) used a multiple baseline design with a reversal. All authors reported an increase in the desired behavior (e.g., fidelity of implementation), and all but one study (Hawkins, 2019) distributed a social validity survey following the intervention's completion. Each author reported high satisfaction levels from each survey. Just over half of the authors (54%, 6/11) reported conducting sessions across generalization and/or maintenance. Bowhers (2020) only reported maintenance measures following the intervention, and the remaining five authors reported generalization and maintenance. Generalization across studies included asking participants to engage with a novel stimulus (e.g., new BCBA, novel fieldwork form). Authors reported measuring maintenance across studies between one session following intervention mastery and as far out as 6 weeks following mastery in intervention. None of these studies included a takeaway tool (e.g., a task analysis).

Survey-Based and Mixed-Method Studies

Table 3 contains our findings related to survey and mixed-method articles. Across the nine included articles, authors used a survey design to answer questions about supervision; 2131 individuals responded across those surveys (Mdn = 236.5; range: 39–575). Respondents included certified supervisors across all levels (i.e., BCBAs, BCBA-Ds) and trainees. Although there were missing descriptions from some articles regarding what percentage of the survey needed to be completed to be included in the authors’ analysis, the range of stated inclusion was between completing 30% of the survey, multiple sections of the survey, and 100% of the survey.

Aims and research questions from surveys differed across all nine studies. They included: (1) areas of supervision that need improvement; (2) a correlation between work demand and burnout; (3) experiences with virtual supervision; (4) compassion, empathy, and building relationships with caregivers; (5) use of recommended supervision behaviors and practices with trainees; (6) preservice training within employment; (7) diversity issues in graduate-training programs; (8) supervision practices and clinicians' overall level of satisfaction; and (9) supervision practices in Australia.

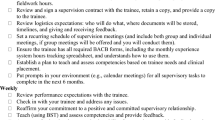

As reported by the authors, there were nine general findings from the survey-based studies. These findings included: (1) BCBAs supervising trainees implement a variety of practices associated with high-quality supervision; (2) supervision has the potential to shape competent supervisees who act in an ethical and professional manner, and high levels of work demands are positively correlated with high work demands and low job satisfaction; (3) BCBAs can provide virtual supervision that is acceptable and feasible; (4) training programs for BCBAs are not explicitly teaching skills in the area of compassion, empathy, and building therapeutic relationships with caregivers; (5) there is wide variability in how often respondents engage in recommended supervision practices; (6) only a slight majority of respondents indicated they received supervisory training before working independently; (7) respondents perceived their training to be lacking in the area of cultural competency; (8) results revealed 20 key supervision components and 19 key supervision satisfaction components; and (9) there are few certified individuals providing supervision in Australia and are doing so across various modalities (e.g., in person, virtually). One only article (i.e., Sellers et al., 2019) included a takeaway tool, which was a supervisor to-do list and was not empirically validated. Finally, only one article (i.e., Dounavi et al., 2019) conducted statistical analyses beyond calculating descriptive statistics.

One study (i.e., Garza, 2018) used a mixed-methods approach to analyze a university-based practicum site in which supervision was provided to trainees. They used survey-style interviews and descriptive analyses to identify disconnects within the practicum site at various levels of the organization (e.g., performer level). They identified 21 disconnects, such as a lack of inclusion of job information for supervisors and failure to incorporate performance data from "on-the-job" training into future iterations of the training procedure.

Discussion-Style Articles

Twenty articles were discussion-style and all had differing aims and purposes. For ease of presentation, these data (i.e., the aims and purposes of all 20 articles, according to the authors of those articles) are presented in their entirety in the second column of Table 4. Consider Sellers, LeBlanc et al. (2016) as an example. These authors described and provided recommendations for identifying and addressing barriers to success in supervision. As an additional example, consider Hartley et al. (2016), who discussed an apprenticeship style and model of supervision. Of the 20 discussion-style articles, nine (i.e., Andzik & Kranak, 2021; Britton et al., 2021; Fraidlin, McElroy et al., 2022; Fraidlin, Van Stratton et al., 2022; Garza et al., 2018; Gatzunis et al., 2022; LeBlanc & Nosik, 2019; Ninci et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2016) included a takeaway tool.

Andzik and Kranak (2021) provided four takeaway tools all relating to soft skills, including a needs assessment for trainees, a checklist for interpersonal skills, exemplars of exercises or strategies when providing demonstrations of soft skills, and a sample checklist for evaluating soft skills. Britton et al. (2021) included a checklist readers could use to monitor compliance with organizational policies and procedures. Fraidlin, McElroy et al. (2022) provided three takeaway tools, including an email template, a supervision self-monitoring tool, and a recommendation action-item checklist. Fraidlin, Van Stratton et al. (2022) supplied practice activities for providing peer feedback. Garza et al. (2018) offered five takeaway tools including an example job model, task analysis template, storyboard template, Supervision Feedback and Goal Setting Form, and a template for establishing goals and deadlines. Gatzunis et al. (2022) included a self-assessment for providing culturally responsive supervision. LeBlanc and Nosik (2019) provided two takeaway tools for planning and leading effective meetings. These tools were a checklist for planning, leading, and evaluating meetings and rules for meeting participation. Ninci et al. (2021) provided three takeaway tools related to maintaining supervision systems via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, including a client or family needs assessment, a trainee needs assessment and a fieldwork plan. Turner et al. (2016) presented a Supervision Monitoring and Evaluation form consistent with the BACB Supervisor Training Curriculum. None of these collective takeaway tools were empirically validated in corresponding studies.

Discussion

We conducted the first and most comprehensive systematic review of research and publications surrounding supervision on the part of BCBAs as it relates to trainees. Indeed, the results of this review indicate that supervision has been a contemporary area of interest in the published literature, and great work is being done in this area. An overwhelming majority (i.e., 50%, 20/40) of all articles were discussion-style, all of which were published. These discussion-style articles provided invaluable information primarily about behaviors in which supervisors should engage in while providing supervision (e.g., LeBlanc & Nosik, 2019; Sellers, Valentino et al., 2016). Authors of discussion-style articles described skills and characteristics deemed critical to BCBAs providing supervision and ways BCBAs might structure supervision to be as effective as possible (Garza et al., 2018; Hartley et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2016; Valentino et al., 2016). Although these discussion-style articles provide essential information and guidance for BCBAs providing supervision, they offer three areas upon which researchers could (and should) capitalize.

First, supervision recommendations provided in discussion-style articles are based largely in part on the authors' vast experience and expertise, tangentially related research from organizational behavior management, or responses from surveys (e.g., Sellers et al., 2019). This means that these recommendations have yet to be directly empirically validated within the context of supervision—the same is true of any takeaway tools provided in those articles (e.g., trainee needs assessments; Ninci et al., 2021). As such, the functional relation between recommended supervision practices and trainee outcomes is unknown. In other words, it is unknown if currently published recommendations have led or would lead to improved supervisory repertoires. To be clear, this is not to say the recommendations should not be used, followed, or are unwarranted or ill-advised. Rather, supervision provides an area for innovative applied, highly socially significant studies on the part of researchers, as well as clinicians and practitioners who wish to conduct research (see Valentino, 2022, for a discussion; Valentino & Juanico, 2020; Wolf, 1978). As such, future researchers ought to consider selecting and evaluating recommendations and takeaway tools provided by the reviewed studies directly in the context of supervision.

As an example of future research opportunities, there have been 20 takeaway tools provide that have not yet been empirically validated (Table 4), with each tool providing an opportunity for a study to validate its use. Another example of a future research opportunity is to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of published takeaway tools. That is, a few researchers provided and suggested supervisors should use several detailed and specific tools in their supervisory practice. And many of those tools appear beneficial yet potentially cumbersome. Put another way, data-based studies are necessary to confirm the validity, acceptability, and feasibility of the many recommendations and tools that have already been provided.

Further, a few specific lines of supervision research seem well-suited to translational research because of the ease of recruiting participants that are like behavior technicians serving clients without the danger of providing poor supervision that might negatively affect the quality of care for clients (Mace & Critchfield, 2010; Vollmer, 2011). Future researchers could experimentally compare the effects on the feedback receiver when the language differences suggested in LeBlanc, Sellers et al. (2020) such as "do" statements and "don't" statements are used to provide feedback. The effects could be examined on changes in performance in a laboratory task as well as social validity measures related to the perception of the feedback in terms of support and personal appeal. Given that no one is likely to exclusively use one set of those statements versus the other, the studies could even parametrically compare different proportions of do versus don't feedback statements.

Second, most of the recommendations and discussion-style articles were aimed towards supervisors rather than trainees. Likewise, intervention studies that included trainees as participants—all of which were unpublished—were focused on improving supervisory skills that would be more applicable to when those trainees themselves are supervisors (e.g., Yakich, 2020). Trainees will surely benefit from discussion-style articles aimed towards supervisors and learning supervisory skills when they serve as participants, because they will collectively lead to those trainees (presumably) being effective supervisors. However, the supervision experience and relationship are bidirectional (LeBlanc, Sellers et al., 2020). This means there are skills and behaviors specifically related to and should be engaged in by trainees, which in turn affect and influence the supervisor (e.g., feedback reception). Only two articles (one survey, one discussion-style article) in this review were focused explicitly on behaviors or experiences of or recommendations for trainees (see Helvey et al., 2022; Simmons et al., 2021). Thus, future researchers should consider (1) examining strategies for teaching trainee-specific behavior and (2) expanding upon some of the recommendations for trainees offered by Helvey et al. (2022).

Third, a majority (i.e., 36%, 15/40) of all supervision articles irrespective of their type (e.g., intervention study) were authored by some combination of the top three authors. In other words, three authors contributed the majority of all supervision-related articles. These individuals are arguably both pioneers and leaders in this area, as evidenced by the extent of their contributions, as well as their popularity as conference speakers on the topic (Heinicke et al., 2022; Kranak et al., 2022). Their contributions have had and will continue to have an impact on supervisors for the foreseeable future. At the same time, given that these recommendations and this work are coming from a relatively homogenous group, they might not have generality to all areas and aspects of supervision (Branch & Pennypacker, 2013; Hagopian, 2020; see Witts, 2018, for an example). Therefore, we would encourage researchers to follow the example of these influential leaders on this topic and consider contributing to this research base, offering potentially alternative approaches, viewpoints, and strategies for supervision.

In addition, most supervision-related work appeared in one journal (i.e., Behavior Analysis in Practice), and this outlet makes sense considering the audience and scope of the work. However, if we are to expect research and work related to supervision to continue to advance, it is important that this work be published in a variety of behavior-analytic outlets so that multiple audiences are being exposed to and (it is hoped) inspired by this work. Behavior analysts would appear to have an opportunity to significantly contribute to the larger supervision research across fields through discussion and, more importantly, empirical works. Behavior analysis' creative and exacting methodologies would aide other fields in advancing their own supervision research. As such, behavior-analytic researchers might consider disseminating and publishing in outlets outside of typical behavior-analytic publication venues such as The Clinical Supervisor, The Journal of Educational Supervision, or Clinical Supervision.

There are three main limitations to this systematic review. First, and applicable to any systematic review, it is possible that a few relevant articles may have been published during the time this article was submitted and under review. However, considering the number of articles that met our inclusion criteria, it is unlikely that if this occurred, the number of articles published while under review that would have been included is astronomical. Second, there may be other supervision resources for BCBAs and trainees that do not appear in peer-reviewed literature or theses/dissertations. For example, given the continuing education and supervision training requirement, many keynote/invited addresses, or general presentations, as well as workshops at conferences have been focused on supervision as of late. Moreover, companies might also offer their own in-house supervision assessments or training to their employees (e.g., Trumpet Behavioral Health Clinical Competency Assessment and Support System: TBH C-CASS; Trumpet Behavioral Health, n.d.). Though not available to BCBAs broadly, it is encouraging to know that these materials exist for those individuals in particular. Third, we did not include articles that focused broadly on topics typically considered a part of supervision (e.g., feedback, self-assessment) outside of the context of supervision. Supervision is a unique and distinct context that comprises a bidirectional relationship between a supervisor and a trainee (see LeBlanc, Sellers et al., 2020). Thus, including all articles that focused on some component of supervision would have been arduous and likely ill-advised (e.g., feedback via public posting is unlikely to be amenable to supervision). In any case, it remains that very few experimental evaluations of interventions are occurring directly within the context of supervision.

In sum, 40 articles related to BCBA supervision and trainees have been published (or completed in the case of theses/dissertations). Most of these articles offer valuable recommendations and considerations for supervisors. Majority of the research related to supervision has been survey-based in nature, and intervention-based studies have largely not been published. Thus, supervision provides researchers with an area to conduct innovative applied research. This is particularly necessary given the gravitas of supervision. At the same time, a lack of empirical intervention studies might also speak to the difficulty of implementing rigorous experimental methods typically required for publication. However, from our perspective, this difficulty ought to be seen as an opportunity rather than an impediment (Valentino, 2022; Valentino & Juanico, 2020). As nearly all intervention studies were unpublished, perhaps we might see an influx of some published versions in the future. In any case, it is hoped that the data and discussion contained herein will lead to sorely needed experimental work related to and within the context of supervision while tempering fervor for discussion-based articles. Supervision serves as the impetus for creating future quality supervisors. We applaud the authors who have contributed to this body of work and hope this review and discussion encourages future research related to supervision.

Data Availability

All analyses were conducted on publicly available data. All data beyond that contained herein are available from the corresponding author upon very reasonable request.

Notes

Note that throughout this manuscript, “trainee” refers to an individual requiring supervision because they accrue hours to become a BCBA.

BCBA and supervisor will be used interchangeably given BCBAs are the individuals functioning as supervisors in this context.

Note that “discussion” does not refer to the specific Discussion section of an article, but rather the article overall in a molar sense.

Carroll et al. (2022) included two studies in their article.

References

*References included in review and analysis

*Andzik, N. R., & Kranak, M. P. (2021). The softer side of supervision: Recommendations when teaching and evaluating behavior-analytic professionalism. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice, 21(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/bar0000194

*Atkinson, R., Parry-Cruwys, D., & MacDonald, J. (2022). Training graduate students to enter fieldwork data using asynchronous online instruction. Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00732-6

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2018a). A summary of ethics violations and code-enforcement activities. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-violations-and-code-enforcement-activities

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). Supervision, assessment, training, and oversight. https://www.bacb.com/supervision-and-training/

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020, August). BACB newsletter. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/Aug2020_Newsletter/

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2018b). BACB newsletter. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/Mar2018_Newsletter/

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022, March). BACB newsletter. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/Mar2022_Newsletter/

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2013). BACB newsletter: Special edition on new standards. http://bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/BACB_Newsletter_2-13.pdf

Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2021). US employment demand for behavior analysts: 2010–2021. https://www.bacb.com/team-view/us-employment-demand-for-behavior-analysts-2010-2020/

*Bowhers, A. E. (2020). Toward an evidence-based supervision model of independent fieldwork (Order No. 27959028) [Doctoral dissertation, Simmons University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Branch, M. N., & Pennypacker, H. S. (2013). Generality and generalization of research findings. In G. J. Madden, W. V. Dube, T. D. Hackenberg, G. P. Hanley, & K. A. Lattal (Eds.), APA handbook of behavior analysis, Vol. 1: Methods and principles (pp. 151–175). American Psychological Association.

Britton, L. N., & Cicoria, M. J. (2019). Remote fieldwork supervision for BCBA trainees. Elsevier.

*Britton, L. N., Crye, A. A., & Haymes, L. K. (2021). Cultivating the ethical repertoires of behavior analysts: Prevention of common violations. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14, 534–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00540-w

*Brodhead, M. T. & Higbee, T. S. (2012). Teaching and maintaining ethical behavior in a professional organization. Behavior in Practice, 5(2), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391827

Carr, J. E., & Nosik, M. R. (2017). Professional credentialing of practicing behavior analysts. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 4(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216685861

*Carroll, R. A., Preas, E. J., & Paden, A. R. (2022). Training supervisors to provide performance feedback using video modeling with voiceover instructions: A replication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 55(2), 603–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.908

*Conners, B., Johnson, A., Duarte, J., Murriky, R., & Marks, K. (2019). Future directions of training and fieldwork in diversity issues in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(4), 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00349-2

Corporation for Digital Scholarship. (2022). Zotero. [Computer software]. https://www.zotero.org.

*Cruz, Y. (2019). Competency-based clinical supervision in applied behavior analysis [Doctoral dissertation, Nova Southeastern University]. NSUWorks. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/fse_etd/251/

*DiGennaro Reed, F. D. & Henley, A. J. (2015). A survey of staff training and performance management practices: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-015-0044-5

*Dounavi, K., Fennell, B., & Early, E. (2019). Supervision for certification in the field of applied behaviour analysis: Characteristics and relationship with job satisfaction, burnout, work demands, and support. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 16(12), 2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122098

*Dubuque, E. M. & Dubuque, M. L. (2018). Guidelines for the establishment of a university-based practical training system. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 11(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0154-8

*Fraidlin, A., McElroy, A., Moses, K., Jenssen, K., & Van Stratton, J. E. (2022). Designing a successful supervision journey: recommendations and resources for new BCBA supervisors. Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00728-2

*Ford, K. C. (2020). Supervision practices and predictors of supervision satisfaction for clinicians providing behavioral sciences for individuals with ASD [Doctoral dissertation, University of California Santa Barbara]. eScholarship. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5h8903fr

*Garza, K. L. (2018). Further development of a supervision system for behavior analysis to support evidence-based supervision practices [Doctoral dissertation, Western Michigan University]. ScholarWorks@WMU. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3229/

*Garza, K. L., McGee, H. M., Schenk, Y. A., & Wiskirchen, R. R. (2018). Some tools for carrying out a proposed process for supervising experience hours for aspiring board certified behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 11(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-017-0186-8

*Gatzunis, K. S., Edwards, K. Y., Rodriguez Diaz, A., Conners, B. M., & Weiss, M. J. (2022). Cultural responsiveness framework in BCBA supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00688-7

Gopalakrishnan, S., & Ganeshkumar, P. (2013). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. Journal of Family Medicine & Primary Care, 2(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.109934

*Greeny, K. (2021). Supervision in ABA: Implementing a structured supervision tool [Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington]. ResearchWorks Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/1773/48010

Greer, R. D. (2002). Designing teaching strategies: An applied behavior analysis systems approach. Academic Press.

Hagopian, L. P. (2020). The consecutive controlled case series: design, data-analytics, and reporting methods supporting the study of generality. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(2), 596–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.691

*Hajiaghamohseni, Z., Drasgow, E., & Wolfe, K. (2021). Supervision behaviors of board certified behavior analysts with trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00492-1

*Hartley, B. K., Courtney, W. T., Rosswurn, M., & LaMarca, V. J. (2016). The apprentice: An innovative approach to meet the behavior analysis certification board's supervision standards. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0136-x

Hartling, L., Featherstone, R., Nuspl, M., Shave, K., Dryden, D. M., & Vandermeer, B. (2017). Grey literature in systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-English reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC: Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0347-z

*Hawkins, A. (2019). Evaluating the effects of behavioral skills training [Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University]. RUCore. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/61632/

Heinicke, M. R., Juanico, J. F., Valentino, A. L., & Sellers, T. P. (2022). Improving behavior analysts' public speaking: Recommendations from expert interviews. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(1), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00538-4

*Helvey, C. I., Thuman, E., & Cariveau, T. (2022). Recommended practices for individual supervision: Considerations for the behavior-analytic trainee. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(1), 370–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00557-9

*Hunsinger-Harris, M. L. (2020). An analysis of the effect of an online training on culturally sensitive verbal behavior of supervision in a university-based supervision experience (Order No. 27995337). [Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2428549488/fulltextPDF/B102C95846854890PQ/1?accountid=12924

Kazemi, E., Rice, B., & Adzhyan, P. (2018). Fieldwork and supervision for behavior analysis. Springer.

Kranak, M. P. (2022). Put out the fire before it spreads: On equipping behavior analysts with strategies to mitigate burnout. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 22(4), 404–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/bar0000255

Kranak, M. P., Hall, H., & Jones, C. (2022). Excuse me, I’m speaking: Analysis of women’s representation as keynote and invited speakers in behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00755-z

*LeBlanc, L. A., & Luiselli, J. K. (2016). Refining supervisory practices in the field of behavior analysis: Introduction to the special section on supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 271–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0156-6

*LeBlanc, L. A., Taylor, B. A., & Marchese, N. V. (2020). The training experiences of behavior analysts: Compassionate care and therapeutic relationships with caregivers. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(2), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00368-z

*LeBlanc, L. A., & Nosik, M. R. (2019). Planning and leading effective meetings. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 696–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00330-z

LeBlanc, L. A., & Sellers, T. P. (2022). The consulting supervisor's workbook: Supporting new supervisors. Key Press.

LeBlanc, L. A., Sellers, T. P., & Ala’i, S. (2020). Building and sustaining meaningful and effective relationships as a supervisor and mentor. Sloan.

Luiselli, J. K. (2017). Applied behavior analysis advanced guidebook: A manual for professional practice. Elsevier.

Mace, F. C., & Critchfield, T. S. (2010). Translational research in behavior analysis: historical traditions and imperative for the future. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 93(3), 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.2010.93-293

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stem, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC: Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

*Ninci, J., Čolić, M., Hogan, A., Taylor, G., Bristol, R., & Burris, J. (2021). Maintaining effective supervision systems for trainees pursuing a behavior analyst certification board certification during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(4), 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00565-9

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906.

*Parry-Cruwys, D., Atkinson, R., & MacDonald, J. (2022). Teaching graduate students to identify and adhere to practicum requirements. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(2), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00571-x

*Piazza, J. (2021). Aspiring supervisor training: Implementing a training package to instruct evaluating ethical scenarios (Order No. 28647455). [Doctoral dissertation, Endicott College]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2564931453?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

Reid, D., Parsons, M., & Green, C. (2021). The supervisor's guidebook: Evidence-based strategies for promoting work quality and enjoyment among human service staff (2nd ed.). Charles C. Thomas.

*Sellers, T. P., Ala’i-Rosales, S., & MacDonald, R. P. F. (2016). Taking full responsibility: The ethics of supervision in behavior analytic practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0144-x

Sellers, T. P., & LeBlanc, L. A. (2022). The new supervisor's workbook: Success in the first year of supervision. Key Press.

*Sellers, T. P., LeBlanc, L. A., & Valentino, A. L. (2016). Recommendations for detecting and addressing barriers to successful supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0142-z

*Sellers, T. P., Valentino, A. L., & LeBlanc, L. A. (2016). Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0110-7

*Sellers, T. P., Valentino, A. L., Landon, T. J., & Aiello, S. (2019). Board certified behavior analysts' supervisory practices of trainees: Survey results and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 536–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-0

*Shook, G. L., Ala’i-Rosales, S., & Glenn, S. (2002). Training and certifying behavior analysts. Behavior Modification, 26(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445502026001003

Silbaugh, B. C., & El Fattal, R. (2022). Exploring quality in the applied behavior analysis service delivery industry. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(2), 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00627-y

*Simmons, C. A., Ford, K. A., Salvatore, G. L., & Moretti, A. E. (2021). Acceptability and feasibility of virtual behavior analysis supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 14(4), 927–943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00622-3

*Slanzi, C. M., & Sellers, T. (2022). Paying for supervision: Barriers, solutions, and opportunities. Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00727-3

Theisen, B., & Bird, Z. (2015). BCBA reference manual (TrainABA Supervision Curriculum). Bx Dynamic Press.

Theisen, B., Bird, Z., & Zeigler, J. (2015). BCBA independent fieldwork (TrainABA Supervision Curriculum). Bx Dynamic Press.

Trumpet Behavioral Health. (n.d.). Trumpet behavioral health clinical competency assessment and support system: TBH C-CASS.

*Turner, L. B., Fischer, A. J., & Luiselli, J. K. (2016). Towards a competency-based, ethical, and socially valid approach to the supervision of applied behavior analytic trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s4061-016-0121-4

Valentino, A. (2022). Applied behavior analysis research made easy: A handbook for practitioners conducting research post-certification. Context Press.

Valentino, A. L., & Juanico, J. F. (2020). Overcoming barriers to applied research: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(3), 894–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00479-y

*Valentino, A. L., LeBlanc, L. A., & Sellers, T. P. (2016). The benefits of group supervision and a recommended structure for implementation. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 320–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0138-8

Vollmer, T. R. (2011). Three variations of translational research: Comments on Critchfield (2011). The Behavior Analyst, 34(1), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392231

Weiss, M. J., & Shook, G. L. (2010). Resources on training requirements for applied behavior analysts: The Behavior Analyst Certification Board and the autism special interest group consumer guidelines. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/15021149.2010.11434345

Weiss, M. J., Tereshko, L., Bowman, K., Marshall, K., & Rose, K. (2022). In J. B. Leaf, J. H. Cihon, J. L. Ferguson, & M. J. Weiss (Eds.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis interventions for autism. (Autism and child psychopathology series; Effective collaboration: Maximizing outcomes in autism intervention in an interdisciplinary model (pp. 125–149). Springer.

Witts, B. N. (2018). An external review of the conclusion regarding the PEAK direct training module. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51(3), 719–737. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.491

Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: the case for subjective measurement of how applied behavior is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203

*Yakich, T. (2020). Effects of publicly-posted and vocal feedback on supervision practices of board certified behavior analysts (Order No. 27959939). [Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2430404649?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

Consent to Participate

No participants were included in this review article. Thus, informed consent and institutional approval was not needed

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kranak, M.P., Andzik, N.R., Jones, C. et al. A Systematic Review of Supervision Research Related to Board Certified Behavior Analysts. Behav Analysis Practice 16, 1006–1021 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-023-00805-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-023-00805-0