Abstract

Research indicates widespread unhealthy eating habits among college students, posing long-term health risks. This study at a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) aimed to explore the perceived obstacles and facilitators to healthy eating among college students, using the social ecological model (SEM). Through focus group discussions and key informant interviews, the study identified several barriers to healthy eating, including challenges in accessing federal food assistance resources, gaps in nutrition knowledge, cost concerns, limited food variety on campus, difficulty accessing grocery stores, and a lack of cooking skills. To address these barriers, participants suggested various solutions, such as implementing cooking demonstrations, providing nutrition education, increasing food variety on campus, offering gardening opportunities, adjusting cafeteria hours for more flexibility, making fresh produce more available on campus, assisting students in accessing federal food assistance programs, and providing transportation to nearby grocery stores. The findings highlight the need for targeted interventions to promote healthier dietary behaviors among college students, particularly those attending HBCUs. By addressing the identified barriers and implementing the suggested solutions, initiatives can be developed to support students in making healthier food choices, ultimately reducing long-term health risks associated with unhealthy eating habits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Poor nutrition and associated adverse health outcomes are pressing public health issues among college populations in the United States [1]. Studies consistently highlight concerning trends of unhealthy diets, weight gain, disordered eating, and increased chronic disease risk beginning in early adulthood and persisting through higher education [2, 3]. For example, research shows declines in consumption of fruits, vegetables, fiber, and key micronutrients coupled with increased intake of fat, sugar, and overall calories as students transition into college environments [4,5,6]. These shifts correspond with lifestyle changes like irregular meals, increased snacking and eating out, alcohol consumption, and stress [7]. Consequently, nutrition-related conditions like hypertension, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and certain cancers emerge in early adulthood and currently burden substantial segments of college populations nationwide [8]. These nutrition issues can also negatively impact academic achievement, workforce readiness upon graduation, and the trajectory of chronic diseases long-term when left unaddressed [9].

College students have a unique demography when it comes to their eating habits and nutrition. They often face numerous challenges and barriers that can hinder their ability to maintain a healthy diet. These challenges can vary from limited time and financial constraints to the prevalence of unhealthy foods on campus [6]. The college years are a critical period for the development of lifelong health behaviors, and understanding the barriers and solutions to healthy eating in this context is crucial for the overall well-being of students. Significant disparities exist across racial/ethnic groups and college settings. Studies consistently report even higher rates of overweight, obesity, diabetes, and metabolic abnormalities among racially minoritized students, including those at minority-serving institutions (MSI) such as HBCUs relative to other universities [10,11,12]. These nutrition-related health disparities often have roots in early life inequality yet widen further amid college contexts like Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs) and HBCUs with high enrollment of first-generation, lower-income, and marginalized students of color who disproportionately face food and housing insecurity, financial constraints, and additional obstacles navigating college life [9, 13].

Understanding unique barriers faced by underserved students in accessing, affording, and choosing healthy foods is crucial to promoting equitable campus environments that foster instead of hinder health, well-being, and success. HBCUs play a pivotal role in higher education, fostering the intellectual and cultural growth of a diverse student population. Despite their significance, HBCUs face unique challenges, and one such challenge is the promotion of healthy eating habits among their students [10]. However, research on individual and environmental determinants of dietary behaviors among racially diverse college populations has heavily emphasized predominantly white institutions, with few studies focused on minority-serving institutions [14]. There are also factors that can enable healthy eating among college students and create an environment that supports their nutritional needs. Perspectives from students and key stakeholders are needed to elucidate multi-level barriers and potential solutions specific to HBCU contexts toward reducing nutrition-related disparities. Consistent with social ecological frameworks, individual knowledge and motivations, social norms and supports, living conditions, institutional policies, and accessibility of healthy options within campus food environments interact to shape behaviors [15, 16]. These intricate relationships are best captured by qualitative investigations that value student voice and lived experience above reductionist surveys alone. Policy and customized, culturally appropriate initiatives that address structural gaps in campus resources, programs, and capacity to support diverse students in eating well can be informed by such observations. This helps them succeed academically and may lessen the burden of increasing chronic diseases that they are disproportionately affected by in later life [9].

This study therefore applies a qualitative approach to identify barriers and enablers to healthy eating experienced specifically among racially diverse students at an HBCU located in Texas. This study is particularly relevant as it focuses on an HBCU located in a food desert in Texas and made up of about 83.9% Blacks or African Americans. A food desert is an area with limited access to affordable and nutritious food, which exacerbates the challenges students face in maintaining healthy eating habits. Limited access to fresh produce and healthy food options forces students to rely on fast food and convenience stores, which typically offer less nutritious options. This environmental factor, combined with socioeconomic factors, cultural preferences, and the historical context of HBCUs, makes it more difficult for these students to adopt and maintain healthy dietary habits [12].

The primary objective of this study was to identify and analyze the barriers that impede students in the HBCU from adopting and maintaining healthy eating habits using the social ecological model (SEM). Additionally, the study aimed to garner potential solutions and interventions to overcome these barriers, promoting a culture of wellness within the HBCU community. Given the growing concern about the health of college-aged populations, this study contributes to the broader field of public health knowledge. Insights gained from HBCU-specific research can inform evidence-based interventions applicable to similar institutions, enriching the understanding of health dynamics among diverse student groups. Understanding the barriers to healthy eating using the SEM model can inform the creation of policies that support and promote a culture of wellness within HBCUs, fostering a healthier environment for their students.

Method

Study population and design

The World Health Organization’s social ecological model (SEM) offers a comprehensive framework for comprehending the diverse factors influencing an individual’s health and well-being. These factors encompass personal beliefs, interpersonal relationships, community policies, and environmental structures. The model, consisting of four interrelated components, acknowledges the intricate interplay of influences on health, particularly those related to social determinants, fostering lasting health promotion efforts among health professionals [17]. This model, organized into four interconnected components, recognizes the diverse factors shaping health outcomes. At its core lies the individual/interpersonal level, focusing on factors shaping an individual’s health and behavior, such as personal beliefs, attitudes, and unique characteristics. Moving outward, the interpersonal level encompasses the dynamics of relationships among individuals, including interactions within families, friendships, and broader social networks. The systems/community level addresses the healthcare delivery systems and broader infrastructure that can either support or impede health-promoting behaviors, spanning institutions like schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods. Lastly, the outermost layer is the policy level, encompassing local, state, and federal rules, policies, and laws regulating access to services, availability, legal rights, and protections [18].

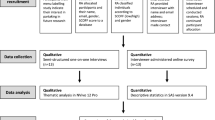

A qualitative approach comprising two sample groups was used to assess and obtain an understanding of the obstacles and possible solutions to healthy eating among the students of an HBCU located in a food desert at Texas. Key informant interviews (KIIs) were held with purposively selected significant stakeholders who had direct dealings with the food security initiatives on campus such as employees of the food pantry and health services, extension agents, the city community leaders, the cafeteria staff, students and staff of the student-led garden, the meal sharing program, and student government. E-mail messages were sent to stakeholders to inform them about the study and request their available times for an interview. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were also held among students. As part of their informed consent, participants got information about the study and all participants provided written consent. The research was authorized by the University Institutional Review Board. For the FGDs, participants were recruited via flyers that were distributed across the University facilities, and via email using a college student database. In the advertisement sheet, a link to an online survey was provided to facilitate recruitment and to give subjects the essential background to the study. Students who met the inclusion criteria were contacted via text message and email to provide their availability for the FGD sessions and only the eight students who responded participated in the FGDs. The discussion sessions were held both in-person and via zoom depending on the preference of the participants. Eligible participants included students who > / = 18 years of age, are food insecure, and/or have a diet-related chronic disease such as obesity, diabetes/prediabetes, or cardiovascular disease as these groups of people are impaired by unhealthy eating (Fig. 1).

Data Collection and Analysis

Fifteen KIIs lasting between 20 and 40 min each and two 60-min FGDs with four students each were conducted. The discussion and interview sessions were audio-recorded and notes were taken by a research observer. Recordings were transcribed, and identifiers were redacted. The structured open-ended questions used in the FGDs and interview guides were provided by the principal investigator of the research team. For the KIIs and FGDs, questions were asked about the participants’ perception of the campus food environment and their experience with the different campus food security initiatives, and the students were further asked about their experience with healthy eating as students. The interviewers recorded the keywords and phrases used by the respondents and occasionally repeated the responses to confirm that they understood and interpreted what they had said. This allowed them to ensure that the data being collected was reliable.

The interviews were transcribed into Microsoft Word, anonymized, reviewed for accuracy, and then uploaded into QSR NVivo 12 Pro (QSR International Pty Ltd. Release 1.0, 2020). Thematic analysis was the method used. The information was coded and examined to identify emerging trends by two members of the research team. Where nodes included similar statements, they were merged. Statements were coded to themes based on concepts conveyed. Text-search queries helped find examples of where a respondent had addressed a theme in another context, and these remarks were parallel-coded [20].

Results

Out of the 15 participants for the KII, there were 6 (40.0%) females and 9 (60%) males, comprising 4 (36.4%) students and 11 (63.6%) members of staff who were key stakeholders of resources on campus put in place to enhance healthy eating. Their years of experience with the phenomenon under investigation ranged from 5 to 30 years. There was a poor response to the call for FGDs hence only eight students participated in the FGDs. They were aged between 19 and 65 years old comprising 4 males and 4 females. Three (37.5%) of them were graduate students, 2 seniors, 2 juniors, and 1 sophomore. Seven (87.5%) resided off campus.

Analysis of the interviews and FGDs identified the challenging themes limiting students’ capability for nutritious diets categorized into three SEM sublevels. Ten subthemes emerged; the themes and their definitions are presented in Table 1. Four of the themes considered hindrances fell within the individual/personal level of SEM, four were within the community/institutional level, while two were classified at the policy/societal level. Nine dominant opportunity areas/solutions also emerged majorly falling within the institutional/community sublevel of SEM as shown in Table 2. Basic information of the participants giving the quotes is given using codes such as FGD_F for a female focus group participant and KII_M for a male key informant participant.

Discussion

The result of this qualitative study identified key enablers and hindrances to healthy eating faced by college students in a HBCU located in Texas. The themes were identified through semi-structured interviews with key informants and FGDs using the SEM as a conceptual framework. The challenging factors ranged from knowledge and accessibility limitations to competing priorities and unfamiliarity with nutritious alternatives. This study uncovered intersections between individual competencies, environmental defaults, and systemic policies impacting students’ dietary patterns. The findings align with and build upon previous research on barriers to healthy nutrition in the college demography where several hindrances emerged from the study, restricting students’ ability to make optimal dietary choices [21, 22]. Financial constraints were a major obstacle, preventing students from affording healthier specialty items. A systematic review by Matias et al. [6] similarly found college students view the expense as a significant barrier, gravitating toward cheaper fast food. The relatively high cost of healthy options is considered a policy-level issue that the government needs to better address; this has posed consistent obstacles, as college budgets often strain to cover basic needs [23]. This emphasizes systemic affordability and food security challenges students face, supporting Payne-Sturges et al.’s [9] insights into lacking nutritional equity on campuses. Students at HBCUs often experience more significant financial challenges compared to those at PWIs, limiting their access to healthy food options. Earlier studies [24, 25] found that food insecurity is a prevalent issue among college students, particularly at institutions with a higher proportion of low-income students which significantly hinders their ability to maintain healthy eating habits. Among the community/institutional-level barriers identified is the issue of difficulty with physical access to healthy food options. Many lacked physical access/transportation to full-service grocers, thereby relying on limited, repetitive campus options, this aligns with Nelson et al. [26] identification of environmental factors like minimal supermarket access as key impediments. Stress and time scarcity also hindered healthy eating, as found previously by Choi [27] that academic pressure negatively impacts diet quality among first-year students, also packed scheduling demands and inflexible dining operating hours afforded little time for intentional nutrition. This reinforces a previous study by LaFountaine et al. [28] linking high students’ workloads with food insecurity risks. The longstanding issue of poor nutrition understanding among youth continued in the college setting, aligning with Hilger-Kolb and Diehl’s [29] findings where students struggled to apply nutrition principles unsuited to their lifestyle constraints. Students tended to stick to familiar foods from their upbringing as found in a previous study [30].

Conversely, several enablers were identified to promote healthy eating habits among students some similar to findings from previous studies. Weaving food literacy and lifestyle behavior change concepts into coursework and campus programming sustains education beyond one-off events while aligning health with academic success [31]. Leveraging influential student culture leaders to serve as nutrition ambassadors conducting outreach provides relatable messengers to model attitudes and behaviors [32]. Enhancing affordable transportation assistance to proximal stores combined with subsidized fresh food or prepared meal delivery routing to campus removes locational availability barriers for carless students who cannot easily obtain diverse ingredients for healthful cooking [33]. Increasing variety and encouraging new foods could significantly impact choices [22]. PWIs typically offer a wider variety of healthy food options on campus, including salad bars, vegetarian and vegan options, and other nutritious meals. The availability of these options is highlighted by Laska et al. [34]. Identified enablers offer promising conduits for positively influencing trajectories beyond the campus environment [35].

The hindrances and enablers highlight interdependencies between individuals and systems in shaping dietary behaviors. These findings indicate students face systemic hindrances blocking the capability to consume balanced diets, despite individual motivations [36]. The hindrances found reflect broader systemic barriers facing students seeking healthy options, including time poverty, financial limitations, unfamiliarity with nutrition, and environmental/policy restrictions on campus and in surrounding communities. As Horacek et al. [12] found, students hold positive nutrition attitudes but struggle enacting them amid barriers. The study makes clear that health promotion requires reducing hindrances while incorporating enablers at individual and institutional levels. Campus communities must make the healthy choice the easy choice. The enablers underscore practical, micro-level solutions institutions can implement, like variety, affordability, convenience, and peer demonstration. This interplay of macro-level hindrances and micro-level enablers mirrors the socioecological frameworks put forth by Stok et al. [34]. As the study shows, multidimensional factors intersect, demanding multitiered approaches spanning individual skill building to systemic change. Progress requires multi-sector coordination addressing root access inequalities, while uplifting student voice in decisions impacting their health [14]. This study contributes needed qualitative insights to guide initiatives tackling poor dietary habits contributing to concerning health trends among college populations.

This study has some limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. Conducted at an HBCU located in a food desert, most participants in our qualitative study lived off-campus. The small sample size of the focus group discussions may limit the generalizability of our findings. Despite this, the study’s insights could inform policy development at both institutional and governmental levels in similar contexts. The study on barriers and solutions to healthy eating among students in HBCUs holds significance not only for the well-being of the student population but also for advancing our understanding of health disparities, contributing to public health knowledge, and fostering a culture of wellness within the HBCU community. The outcomes of this research have the potential to drive positive change and serve as a model for promoting health and well-being in diverse educational settings.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Deckers A, Van den Broeck A, Van Hal G, Clarys P, Brunner TA, Mikolajczak J. Obesity, cardiovascular risks and poor lifestyle behavior tend to manifest already in freshman college students. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1334.

Anjali MS. Barriers in adopting a healthy lifestyle: insight from college youth. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2017;6(3):439–49.

LaFave S, Deshpande S, Vidrine JI, Laditka SB. A systematic review of interventions for hispanic college students in the united states: implications for dietetic practice. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(4):665–85.

Sogari G, Velez-Argumedo C, Gómez MI, Mora C. College students and eating habits: a study using an ecological model for healthy behavior. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1823.

Abdelhafez AI, Akhter F, Alsultan AA, Jalal SM, Ali A. Dietary practices and barriers to adherence to healthy eating among King Faisal University students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8945.

Matias SL, Rodriguez-Jordan J, McCoin M. Evaluation of a college-level nutrition course with a teaching kitchen lab. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2021;53(9):787–92.

Das BM, Evans E. Understanding weight management perceptions among first-year black college students: a qualitative study. J Am Coll Health. 2017;65(7):423–33.

Sidik SM, Jonah BA. review on metabolic syndrome in university students. Int Med J Malays. 2017A;16(2):101–8.

Payne-Sturges DC, Tjaden A, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Arria AM. Student hunger on campus: food insecurity among college students and implications for academic institutions. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(2):349–54.

Brown Jennifer J, Chandler Resa M. A survey of HBCU nutritional habits and attitudes about health”. EC Nutrition. 2021;16(9):07–16.

Yancu CN, Lee A, Witherspoon D, & McRae C. 2011 A review of the types of food served in various US institutions of higher education. Coll Stud J

Horacek TM, Publicover NG, Shelnutt KP, White J, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Carey G, Colby S, Brown Onwuegbuzie A, Wernet JGI, Kattelmann KK. Making healthy eating convenient among college students: a systematic review of intervention studies. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(1):1–6.

Bruening M, van Woerden I, Todd M, Brennhofer S, Laska MN, Dunton G. A mobile ecological momentary assessment tool (devilSPARC) for nutrition and physical activity behaviors in college students: a validation study. Health Soc Work. 2020;45(1):13–23.

Carter M, Dubois L, Tremblay MS, Taljaard M. Local context influences university students’ food behaviors and food purchasing decisions. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2018;79(4):176–82.

Chambers EC, Preston KE, Rojas B, Park S, Sanogo K, Treat EA. A case study on socioecological factors at multiple levels associated with edema and nutritional status among pregnant and lactating socioculturally diverse women in rural Nepal. Mater Child Health J. 2018;22(12):1733–45.

Townsend N, Foster C. Developing and applying a socio-ecological model to the promotion of healthy eating in the school. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(6):1101–8.

Moyce S, Comey D, Anderson J, Creitz A, Hines D, Metcalf M. Using the social ecological model to identify challenges facing Latino immigrants. Public Health Nurs. 2023;40:724–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.13214.

Mann G, Greer S, Lambert L, Miller RG. Using the social ecological model to evaluate university faculty and staff perceptions of the campus food environment. Int J Health Promot Educ. 2022;60(3):164–77.

Boyle MA. 2016 “Understanding and achieving behavior change.” In Community Nutrition in Action: An Entrepreneurial Approach, 87–88. 7th ed. Cengage Learning: Boston MA USA

Godrich SL, Lo J, Kent K, Macau F, Devine A. A mixed-methods study to determine the impact of COVID-19 on food security, food access, and supply in regional Australia for consumers and food supply stakeholders. Nutr J. 2022;21(1):17.

Brauman K, Achen R, Barnes JL. The five most significant barriers to healthy eating in collegiate student-athletes. J Am Coll Health. 2023;71(2):578–83.

Leinberger-Jabari A, Al-Ajlouni Y, Ieriti M, Cannie S, Mladenovic M, Ali R. Assessing motivators and barriers to active healthy living among a multicultural college student body: a qualitative inquiry. J Am Coll Health. 2023;71(2):338–42.

Micevski DA, Thornton LE, Brockington S. Food insecurity among university students in victoria: a pilot study. Nutr Diet. 2019;76(4):386–94.

Riddle ES, Niles MT, Nickerson A. Prevalence and factors associated with food insecurity across an entire campus population. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237637.

Patton-López MM, López-Cevallos DF, Cancel-Tirado DI, Vazquez L. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among students attending a midsize rural university in Oregon. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3):209–14.

Nelson MC, Story M, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lytle LA. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: an overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity. 2008;16(10):2205–11.

Choi J. Impact of stress levels on eating behaviors among college students. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1241.

LaFountaine, et al. Food insecurity and dietary intake at a California State University. J Stud Aff Res Pract. 2016;53(4):439–51.

Hilger-Kolb J, Diehl K. ‘Oh God I have to eat something but where can I get something quickly?’—a qualitative interview study on barriers to healthy eating among university students in Germany. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2440.

Evans A, Banks K, Jennings R, Nehme E, Nemec C, Sharma S, Hussaini A, Yaroch A. Increasing access to healthful foods: a qualitative study with residents of low-income communities. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):1–13.

Kolodinsky J, Harvey-Berino JR, Berlin L, Johnson RK, Reynolds TW, et al. Knowledge on current dietary guidelines and food choice by college students: better eaters have higher knowledge of dietary guidance. J American Diet Assoc. 2007;107(8):1409–13.

Scalvedi ML, Gennaro L, Saba A, Rossi L. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake: an assessment among a sample of Italian adults. Front Nutr. 2021;8:714493.

Farris AR, Misyak S, O’Keefe K, VanSicklin L, Porton I. Understanding the drivers of food choice and barriers to diet diversity in Madagascar. J Hunger Enviro Nutr. 2019;15(3):388.

Laska MN, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Dietary patterns and home food availability during emerging adulthood: do they differ by living situation? Public Health Nutr. 2010;2:222–8.

Nelson MC, Kocos R, Lytle LA, Perry CL. Understanding the perceived determinants of weight-related behaviors in late adolescence: a qualitative analysis among college youth. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(4):287–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.05.005.

Pelletier JE, Laska MN. Balancing healthy meals and busy lives: associations between work, school, and family responsibilities and perceived time constraints among young adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(6):481–9.

Acknowledgements

The publication of this paper was supported by the Cooperative Agriculture Research Center of the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources at Prairie View A&M University.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of Advancing Health Through Agriculture through the USDA/ARS (J.A., grant number 58–3091-1–018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted data collection, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Y.O. conducted the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. I.O. and M.I. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and were involved in data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in accuracy and integrity.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing.

Ethical Standard Disclosure

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antwi, J., Olawuyi, Y., Opara, I. et al. Hindrances and Enablers of Healthy Eating Behavior Among College Students in an HBCU: A Qualitative Study. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02108-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02108-8