Abstract

Introduction

Among certain immigrant groups, length of time spent living in the United States (LOT) is associated with poor cardiometabolic health. We aimed to evaluate the association between LOT and cardiometabolic outcomes among US Black adults.

Methods

The National Health Interview Survey is an annual representative survey of non–institutionalized US civilians. We combined 2016–2018 data and included all Black adults (N = 10,034). LOT was defined as the number of years lived in the US, if foreign–born. Obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol were each self–reported. We used logistic regression models to determine whether LOT was associated with cardiometabolic health factors overall and by origin subgroups—US–born non–Hispanic, Hispanic, African–born, and Caribbean/Central American (CA)–born groups.

Results

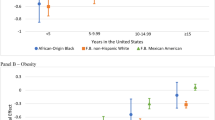

Our study population was 81% US–born non–Hispanic, 5% Hispanic (both foreign– and US–born), 6% African–born, and 6% Caribbean/CA–born groups. Among Black adults, compared with the US–born, being foreign–born with < 15 years in the US was associated with lower odds of obesity (OR: 0.31, 95%CI: 0.23–0.42) and hypertension (OR: 0.35, 95%CI: 0.24–0.49). In subgroup analyses, Caribbean/CA–born individuals with < 15 years in the US had 64% lower odds of obesity (OR: 0.36, 95%CI 0.15–0.84) and 63% lower odds of hypertension (OR: 0.37, 95%CI 0.15–0.88) compared with those with ≥ 15 years.

Conclusion

Shorter LOT was associated with more favorable cardiometabolic health, with differential associations among foreign–born Black adults based on origin. This heterogeneity suggests a need to examine the implications of acculturation in the context of the specific population of interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data used for this study is publicly available from the National Center for Health Statistics.

References

Virani SS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–596.

Markides KS, Rote SJTG. The healthy immigrant effect and aging in the United States and other western countries. 2019;59(2):205–14.

Commodore-Mensah Y, Ukonu N, Obisesan O, Aboagye JK, Agyemang C, Reilly CM, Dunbar SB, Okosun IS. Length of Residence in the United States is Associated With a Higher Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Immigrants: A Contemporary Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(11). https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.116.004059.

Osibogun O, et al. Greater acculturation is associated with poorer cardiovascular health in the multi–ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(8):e019828.

Antecol H, Bedard K. Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography. 2006;43(2):337–60.

Giuntella O, Stella L. The acceleration of immigrant unhealthy assimilation. Health Econ. 2017;26(4):511–8.

Almeida J, et al. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: testing the concept of familism. 2009;68(10):1852–8.

Finch BK, WA Vega, Acculturation stress, social support, and self–rated health among Latinos in California. 2003. 5(3): p. 109–117.

Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. Sex differences in cardiovascular disease risk of Ghanaian-and Nigerian-born west African immigrants in the United States: the Afro-Cardiac study. 2016;5(2):e002385.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):69–101.

Al-Sofiani ME, Langan S, Kanaya AM, Kandula NR, Needham BL, Kim C, Vaidya D, Golden SH, Gudzune KA, Lee CJ. The relationship of acculturation to cardiovascular disease risk factors among US South Asians: findings from the MASALA study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;161:108052.

Bharmal N, et al. The association of duration of residence in the United States with cardiovascular disease risk factors among South Asian immigrants. 2015;17(3):781–90.

Teppala S, Shankar A, Ducatman A. The association between acculturation and hypertension in a multiethnic sample of US adults. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4(5):236–43.

Eamranond PP, et al. Acculturation and cardiovascular risk factor control among Hispanic adults in the United States. 2009;124(6):818–24.

Yi S, et al. Nativity, language spoken at home, length of time in the United States, and race/ethnicity: associations with self–reported hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(2):237–44.

Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. The afro–cardiac study: cardiovascular disease risk and acculturation in west African immigrants in the United States: rationale and study design. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(6):1301–8.

Obichi CC, Dee V. Acculturation, cultural beliefs, and cardiovascular disease risk levels among Nigerian, Ghanaian and Cameroonian immigrants in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2022;24(5):1154–60.

Thomas SC, et al. Length of residence and cardiovascular health among Afro-Caribbean immigrants in New York City. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(3):487–96.

Commodore–Mensah Y, et al, Cardiometabolic health in African immigrants to the United States: a call to re–examine research on African–descent populations. 2015. 25(3): p. 373.

Tamir, C. Key findings about Black immigrants in the U.S. 2022 [cited 2022 December 30]; Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/01/27/key-findings-about-black-immigrants-in-the-u-s/.

Baptiste DL, et al. Heterogeneity in cardiovascular disease risk factor prevalence among White, African American, African immigrant, and Afro‐Caribbean adults: insights from the 2010–2018 National Health Interview Survey. 2022. 11(18): p. e025235.

Chang CD. Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2019;49(1):23–30.

Dunn JR, Dyck I, and medicine, Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: results from the National Population Health Survey. 2000. 51(11): p. 1573–1593.

Sidney S, et al. Recent trends in cardiovascular mortality in the United States and public health goals. JAMA Cardiology. 2016;1(5):594–9.

National Center for Health Statistics. About the National Health Interview Survey. 2022 [cited 2023 January 2]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm.

Klein RJ, Age adjustment using the 2000 projected US population. 2001: Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

IPUMS Health Surveys. NHIS Sample Design. 2023 [cited 2023 January 10]; Available from: https://nhis.ipums.org/nhis/userNotes_sampledesign.shtml#:~:text=The%20NHIS%20is%20a%20complex,primary%20sampling%20units%20(PSUs).

Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. African Americans, African immigrants, and Afro-Caribbeans differ in social determinants of hypertension and diabetes: evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5:995–1002.

Mehta NK, et al. Obesity among U.S– and foreign–born Blacks by region of birth. Am J Preventive Med. 2015;49(2):269–73.

Brown AG, et al. Hypertension among US–born and foreign–born non–Hispanic Blacks: NHANES 2003–2014 data. J Hypertens. 2017;35(12):2380.

Doamekpor LA, et al. Nativity and cardiovascular dysregulation: evidence from the 2001–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(1):136–46.

Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2099–106.

Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: a systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(7):983–91.

Steffen PR, Smith TB, Larson M, Butler L. Acculturation to Western society as a risk factor for high blood pressure: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(3):386–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000221255.48190.32.

Castañeda H, et al. Immigration as a social determinant of health. 2015;36:375–92.

Lacey KK, Powell Sears K, Govia IO, Forsythe-Brown I, Matusko N, Jackson JS. Substance use, mental disorders and physical health of Caribbeans at-home compared to those residing in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120100710.

Gushulak BD, et al. Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. 2011;183(12):E952–8.

Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):903–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl089.

Baptiste DL, et al. Heterogeneity in cardiovascular disease risk factor prevalence among White, African American, African immigrant, and Afro-Caribbean adults: insights from the 2010–2018 National Health Interview Survey. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(18):e025235.

Read M.O. Emerson, Tarlov A. Implications of black immigrant health for US racial disparities in health. J Immigrant Health. 2005;7:205–12.

Thoits PA. Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. Journal of health and social behavior. 2010;51(1_suppl):S41–53.

Horlyck-Romanovsky MF, Fuster M, Echeverria SE, et al. Black Immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean have similar rates of diabetes but Africans are less obese: the New York City Community Health Survey 2009–2013. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6:635–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00562-3.

Horlyck-Romanovsky MF, et al. Black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean have similar rates of diabetes but Africans are less obese: the New York City Community Health Survey 2009–2013. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(3):635–45.

Porter JR, Washington RE. Minority Identity and Self-esteem. Annu Rev Sociol. 1993;19(1):139–61.

Osypuk TL, et al. Are immigrant enclaves healthy places to live? The Multi–ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):110–20.

Sanchez M, et al. Immigration stress among recent Latino immigrants: the protective role of social support and religious social capital. 2019;34(4):279–92.

Sanchez M, et al. The influence of religious coping on the acculturative stress of recent Latino immigrants. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2012;21(3):171–94.

Sanchez M, et al. The impact of religious coping on the acculturative stress and alcohol use of recent Latino immigrants. J Relig Health. 2015;54:1986–2004.

Mohamed B, Cox K, Diamant J, Gecewicz C. Faith among black Americans. Pew Research Center. 2021. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1426078/faith-among-black-americans/. Accessed 2021-02-16

Diamant J. African immigrants in US more religious than other Black Americans, and more likely to be Catholic. Pew Research Center. 2021. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2005027/african-immigrants-in-us/. Accessed 2021-12-07

Scholaske L, Wadhwa PD, Entringer S. Acculturation and biological stress markers: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;132:105349.

Funding

Dr. Tali Elfassy is currently supported by the National Institutes of Health; and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (K01MD014158).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IA: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. LD: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. RAM: methodology, writing—review and editing. JT: writing—review and editing. LV: writing—review and editing. TE: conceptualization, methodology, validation, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Data obtained for this study is de–identified and publicly available.

Consent to Participate

All NHIS respondents provided oral consent prior to participation.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Anikpo, I., Dodds, L., Mesa, R.A. et al. Length of Time in the United States and Cardiometabolic Outcomes Among Foreign and US–Born Black Adults. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01902-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01902-0