Abstract

Objective

To characterize the representation of Black and Hispanic cancer patients in tobacco treatment trials, and to offer recommendations for future research.

Methods

We conducted two systematic searches of the literature (2018, 2021) using 5 databases (MEDLINE via EBSCO, Pubmed, PsycInfo, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE)) to examine the prevalence of tobacco trials that included Black or Hispanic cancer patients. Two coders independently screened all articles at title, abstract, and full-text to identify eligible trials. Information about the proportion of Black and Hispanic patients included, trial design features, and whether the authors analyzed outcomes for Black and Hispanic patients were documented.

Results

Of 4682 identified studies, only 10 published trials included and reported on the rates of Black or Hispanic cancer patients enrolled in their tobacco trial. The proportion of enrolled Black cancer patients ranged from 2 to 55.6%. Only our studies documented enrollment rates for Hispanics, and rates were less than 6%. None of the studies offered strategies to promote or the accrual of Black or Hispanic patients.

Discussion

There remains a large gap in the literature regarding the reach and efficacy of tobacco treatment for Black and Hispanic cancer patients. Black and Hispanic cancer patients remain largely under-represented in tobacco cessation trials, limiting the applicability of existing, evidence-based treatments. To optimize intervention generalizability, future studies should emphasize the targeted recruitment and engagement of these patients in tobacco trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Blacks and Hispanics living in the USA face increased risk for cancer and for worse cancer outcomes, including worse survival [1,2,3]. Cigarette smoking, albeit modifiable, is a known risk factor for at least 12 types of cancers. Despite demonstrating greater interest and efforts to quit, Black and Hispanic smokers are less likely to receive quit advice; initiate, participate in, and comply with tobacco treatment; utilize pharmacological agents to aid cessation efforts; and maintain abstinence after quitting [4,5,6,7,8]. For smokers diagnosed with cancer, continued smoking has the potential to aggravate cancer care, leading to treatment-related side effects, poorer quality of life, increased risk of recurrence, and adverse cancer outcomes [9,10,11,12]. Although 10–30% of cancer patients report continued smoking after a cancer diagnosis [13, 14], given the prevailing evidence, it is possible that these rates are disproportionately higher among Black and Hispanic cancer patients.

A number of researchers have endeavored to decrease the burden of cancer by tailoring tobacco trials to the needs of cancer patients who smoke; yet, it remains unknown if these interventions translate to improvements in smoking outcomes among these two vulnerable groups. This is a critical question; despite national mandates (including the 1993 NIH Revitalization Act), ethnic and racial minorities are generally under-represented in cancer clinical trials, challenging the accuracy and generalizability of trial findings [15]. If issues of non-inclusion or under-representation of Black and/or Hispanic cancer patients extend to tobacco treatment trials, it may risk widening disparities in cancer outcomes [16, 17]. In response to this concern, this systematic review searched and synthesized the literature to (1) characterize the general reporting of Black and Hispanic cancer patients enrolled in tobacco treatment trials, (2) document the proportion of Black and Hispanic patients enrolled, (3) examine the “fit” between a trial’s design and the unique needs of Black and Hispanic cancer patients who smoke, and (4) summarize the reporting of tobacco treatment effects for Black and Hispanic cancer patients. Specifically, this review seeks to answer key questions surrounding the existing tobacco treatment evidence base for tobacco-dependent Black and Hispanic cancer patients, such as: Do existing tobacco treatment trials include Black and Hispanic cancer patients? Are tobacco treatment trials accessible to this population (i.e., are Black and Hispanic patients eligible and able to participate; are trials offered in community settings where these patients commonly present for care; are culturally sensitive study materials and multilingual staff used to promote engagement?)? To what extent do investigators document the use of culturally sensitive approaches to ensure the inclusion and engagement of Black and Hispanic cancer patients? To what extent do investigators address racial/ethnic variables that influence patients’ willingness to participate? Do trials demonstrate equitable efficacy in improving cessation rates in these groups? Understanding the successes and challenges of providing tobacco support to Black and Hispanic cancer patients in the cancer context will help guide the development of efficacious, culturally sensitive smoking cessation interventions that comprehensively address the complex needs of these two vulnerable groups.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Guidelines from 2009. A PRISMA protocol was created and registered under the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42016050547).

Literature Search Strategy

Searches were conducted by a reference librarian (LP) in the following databases with publication dates ranging from the date of inception to January 2021: MEDLINE via EBSCO, Pubmed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Embase. Both controlled vocabulary and text word searches were conducted, as appropriate. To identify and maximize study eligibility, search terms included, but were not limited to the following terms: Hispanic, African American, Black, cessation, intervention, smoking, tobacco, cigarette, and cancer. Members of the study team compiled lists of search terms specific for each database. A qualified research librarian completed a preliminary search of all available articles published on the topic through 05/02/2018 and a second search through (01/15/21), only including studies written in English. A complete description of our Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keyword terms, as well as our exact search strategy, is available upon request. Two independent researchers (JR, NS) also examined the bibliographies of included studies to ensure no additional trials met the inclusion criteria.

Eligibility

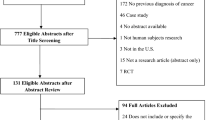

Any smoking cessation intervention trial was eligible for inclusion if participants were adults, had a current or previous cancer diagnosis, and were current cigarette smokers. We excluded case studies as well as trials that did not specify the inclusion of Black or Hispanic participants in their sample. Trials that collapsed all racial and ethnic categories when reporting the demographic make-up of their sample were excluded. Studies were also excluded if participants only smoked other forms of tobacco and not cigarette use. We additionally excluded studies conducted outside of the USA due to differences in racial/sociodemographic make-up and challenges across countries (Fig. 1 outlines eligibility/exclusion breakdown). We did not use time frame restrictions in this study.

Search Strategy and Extraction

To begin the multi-step process to determine eligibility, two independent researchers (BT and NS) conducted an initial screening of all available articles at the title, abstract, and full-text levels. Two additional researchers (JR and NS) completed a secondary review to resolve remaining discrepancies at each of the three levels of screening. These same researchers completed an additional review of all emerging articles since May 2018 through January 2021 to ensure that all eligible articles were included in this systematic review. Articles were discussed in detail among the study team if questions regarding eligibility arose. Figure 1 details this three-tiered process.

After the exclusion and inclusion process, the study team extracted data from eligible studies (n = 10) related to the enrollment and engagement of Black and Hispanic cancer patients in tobacco treatment trials. We created data spreadsheets to organize and extract relevant information from each article. Specifically, our study team extracted data related to the proportion of Black and Hispanic cancer patients enrolled, the type and location of the study, screening and recruitment strategies, identification of culturally sensitive intervention approaches, and reporting of racial/ethnic sub-analyses. In studies that reported a catchment area, census data from the relevant decade was used to ascertain the racial/ethnic demography of the catchment area and compare it to the participant demographics (Table 1). Due to the limited number of eligible articles and the heterogeneity of the study population and treatment designs, findings are summarized narratively rather than statistically.

Quality Assessment

We used the NIH Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies and the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Control Group to determine the quality ratings of the eligible studies [18, 19]. Two researchers independently rated each article as good, fair, and/or poor based on the NIH Quality Assessment. This Assessment addressed treatment allocation, blinding group assignments, drop-out rate, adherence to protocols, outcome assessment and analysis, and other sources of bias. The team discussed rating discrepancies until agreement was reached for all studies.

Results

Prevalence of Tobacco Treatment Trials Including Black and Hispanic Cancer Patients

Approximately 4682 articles were identified, and 3911 were excluded after title review. Furthermore, 771 abstracts were assessed, of which 66 underwent further review. Of the 66 articles reviewed at full-text, Black or Hispanic cancer patients were represented in only 10 (15.2%) studies. Accordingly, only 10 articles met eligibility criteria and were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Quality Assessment. We determined that 2/10 (20%) studies were at high risk for bias (see Table 2). Factors that impacted the quality of the study included randomization, study type, blinding, drop-out rate, and the use of valid and reliable measures. Eight studies were considered to have low risk of bias [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Representation of Black and/or Hispanic Samples

A summary of trial characteristics is noted in Table 1 and Table 3. All 10 trials included Black smokers in their sample, and enrollment rates ranged from 2–55.6%. The one study that reported high enrollment (55.6%) was a non-randomized, cohort study consisting of 18 patients [27]. Only 4/10 studies (40%) documented enrollment rates for Hispanic patients, with rates ranging from < 1–5.2% [21, 23, 25, 26].

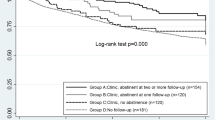

Trial designs varied widely (Tables 1 and 3). Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) utilized physician-based smoking cessation interventions: (1) surgeon or dentist-delivered quit advice and materials [20], (2) cognitive behavioral treatment with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) with an oncologist delivered advice letter [21], and (3) physician-delivered quit advice in accordance with NIH smoking interventions [23]. Browning and colleagues (2000) examined nurse-delivered counseling with pharmacological support and smoking cessation material; however, they used a quasi-experimental design [24]. Specifically, instead of randomizing patients to treatment arms, they compared outcomes in patients who received usual care in the 5 months preceding patients who received the nurse-delivered treatment. Three other RCTs utilized trained counselors to test the effects of behavioral counseling; however, each examined different aspects of tobacco treatment: (1) Park (2020) compared the differences between counseling intensity (short vs. long-term) [25]; (2) Schnoll (2010) tested the effects of behavioral counseling with NRT and bupropion compared to behavioral counseling with NRT and placebo [22]; and (3) Krebs (2019) compared the effects of standard tobacco treatment (i.e., 4 telecounseling sessions with educational materials) to a smoking cessation app paired with standard tobacco treatment [26]. Two trials were smaller, prospective cohort studies that (1) examined the impact of a pocket calendar and physician support [28] and (2) targeted low income and minority smokers to test the feasibility and acceptability of a mindfulness-based smoking cessation medical group visit (Charlot et al., 2019) [27]. One final study examined the feasibility of integrating families into treatment by embedding a family systems-based intervention within an existing tobacco program (Ruebush et al., 2020) [29].

“Fit” between Trial Design and the Needs of Black and/or Hispanic Cancer Patients

Eligibility Criteria. Cancer Type: Nine of the ten studies had explicit criteria regarding cancer type and severity. Three of these focused exclusively on patients with head and/or neck cancers [20, 21] or lung cancer [21, 24] with no restrictions surrounding disease severity or health status. Four studies were open to patients with any cancer diagnosis [22, 23, 26, 29]; however, of these trials, Ruebush [29] was the only one without eligibility restrictions in cancer staging and/or ECOG status. Specifically, Schnoll [22] excluded patients with advanced cancers, those with brain metastases, and patients with chronic health conditions. Schnoll [23] limited inclusion to patients with early-stage cancer; however, it allowed patients with advanced lymphoma to participate if diagnosed with lymphoma, breast, prostrate, or testicular cancer. Eligibility was further restricted to patients who were generally healthy and functional as defined by an ECOG status ≤ 1. One study required that participants be recently diagnosed with cancer in the breast, GI, GU, GYN, head/neck, lung, lymphoma, or melanoma and currently undergoing treatment [25].

Smoking Status: Eight studies had flexible criteria for smoking status (Table 3). Four required that patients report having smoked at least one cigarette in the past 30 days [21, 23, 25, 27], and one study required that patients endorse having used tobacco in the past year [30]. A sixth study enrolled patients who smoked at least 2 daily cigarettes [22], whereas a seventh trial enrolled daily smokers, regardless of cigarette consumption, if they smoked for at least 1 year [24].

Other Criteria: Several of the studies placed additional entry restrictions based on other criteria. Four studies excluded patients based on their mental health status [22, 26, 27, 30] and five excluded patients who did not speak English [20,21,22, 26, 27, 30]. Four studies had specific participation requirements, including having a phone [21, 22, 25, 27] or being able to attend in-person medical care [20, 21].

Recruitment Approach. None of the studies described efforts to target recruitment or oversample enrollment of Black or Hispanic cancer patients (Table 3). Indeed, few offered details regarding targeted recruitment efforts. For instance, only Park (2020) described using recruitment materials in Spanish [25]. One study relied on the electronic health records (EHR) to identify participants [29], whereas another had participating physicians at recruitment sites use standard intake evaluation forms for recruitment [23]. Six studies utilized proactive recruitment efforts, including screening of physician schedules [21, 22, 25] and proactive patient outreach either in-person or by phone [20, 24, 26, 27]. Other than the location of where recruitment was taking place, one study did not identify recruitment details [28].

Recruitment Setting. Two studies did not offer information about recruitment sites [21, 22], precluding one’s ability to determine if the patients enrolled are representative of their institutions’ catchment area. The remaining eight studies were conducted in areas that had relatively large representation of Black patients and variable access to Hispanic populations [20, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. These studies were conducted in Veterans Healthcare Administration Medical Centers (VAs) [28], community-based clinics [27], Academic Medical Centers [23,24,25], as well as across a consortium of academic hospitals [23, 25, 26, 29]. Of these eight studies, six reported enrollment numbers that were not commensurate with the distribution of Blacks and Hispanics patients in their catchment area [23,24,25,26,27,28]. Only three studies enrolled a population of patients that was comparable to, if not surpassed, the ethnic and racial distribution in the surrounding area [20, 27, 29]. Gritz (1993) enrolled patients receiving care across a mix of academic medical centers, VAs, and county hospitals located in Southern California, an ethnically diverse region of the USA [20]. Ruebush (2020) recruited from the North Carolina Hospital Center, an academic medical center [29]. Charlot (2019) recruited from the Boston Medical Center Outpatient Clinic, part of a large, urban, safety-net hospital [27].

Treatment Adaptations. None of the studies directly addressed cultural/racial factors that may impact smoking behavior or outcomes among Black and/or Hispanic patients.

Subgroup Analyses Examining Outcomes for Black and Hispanic Cancer Patients

Five studies did not report racial/ethnic differences in eligibility, enrollment, and drop-out [22, 24, 26, 28, 29]. Additionally, these studies did not examine racial/ethnic differences in cessation outcomes, although most often their sample size precluded their ability to conduct these analyses. The remaining 5 studies examined some differences in study eligibility and retention based on racial/ethnic variables. Gritz [20] investigated reasons for study ineligibility, allowing readers to consider the influence of entry criteria on Black or Hispanic patient enrollment. Similarly, they estimated racial/ethnic differences between study completers and non-completers; however, these analyses combined all racial/ethnic groups into one category. Notably, the authors looked at differences in smoking behavior by race/ethnicity only at baseline. Similarly, Schnoll et al. [23] considered the influence of race/ethnicity among other predictors on 7-day point prevalence. In a later study, Schnoll and colleagues [21] compared patients who declined participation to those who enrolled, and they found that patients who declined were more likely to be diagnosed with head/neck cancers, experience fewer physical health symptoms, reported no intention or had lower readiness to quit, and smoked fewer cigarettes. Charlot [27] noted that smokers who are part of a minority group or of a low socioeconomic status were less likely to utilize pharmacotherapy and behavioral intervention methods; however, they did not conduct formal subgroup analyses on outcomes. Park [25] analyzed differences in study eligibility, randomization and completion based on sociodemographic variables. They noted differences in session 1 completion rates (thus study randomization) between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white patients, with Hispanics being less likely to be randomized. They also acknowledged that the ability to provide pharmacotherapy free-of-cost to patients would not be available in less-resourced clinics.

Discussion

This review is among the first to report critical gaps in the documentation and representation of two populations at high risk for experiencing poorer smoking and cancer outcomes in tobacco treatment trials. Despite our broad inclusion criteria, we identified only 10 tobacco treatment trials conducted with cancer patients that at a minimum detailed enrollment data for either Black or Hispanic cancer patients. Of these 10, only 3 studies [20, 27, 29] demonstrated accrual rates that were either proportionate to the surrounding population or highly representative of the population of Black smokers. Moreover, Hispanics remained largely under-represented across all 10 studies. These findings are disconcerting, as these groups have been evidenced to carry a disproportionate burden of disease, often presenting with more advanced illness, and exhibiting greater barriers to treatment [1, 3, 15, 16, 31]. Nonetheless, these findings corroborate existing reports documenting critical gaps in the inclusion and representation of Black and Hispanic patients in clinical trials [15, 27,28,29,30,31], challenging one’s ability to draw conclusions about the utility of tobacco treatments for these two cancer populations.

Several factors have been purported to explain why Black and Hispanic patients are under-represented in treatment trials, some of which include lack of trial awareness, logistical barriers (e.g., time, transportation, childcare concerns), and provider and research mistrust due to decades of discrimination, microaggressions, and mistreatment by both the medical and research community (e.g., the Tuskegee Syphillis study) [32,33,34, 40]. However, this review expands on these factors by highlighting how our research infrastructure (e.g., trial design and procedures) may serve as another form of structural racism, thereby widening observed disparities in trial participation and outcomes. As noted within this review, shortcomings related to how trials are designed impacts patients’ access to tobacco treatment trials. Access issues have been demonstrated to interfere with the receipt of regular medical care [35], and these challenges may extend to the clinical trial environment. Specifically, the geographical location and institutional setting of trials, often pre-determined by study funds and investigator location, may narrow the eligible pool of participants from the outset [36]. Indeed, most of the trials in this review were conducted in academic medical centers. Black and Hispanic individuals are often underinsured or uninsured, have less access to healthcare, and hold negative perceptions of academic institutions [2, 32, 37], which may deter participation.

Opening trials at community settings or in locations that are financially and logistically accessible to Black and Hispanic communities can offset these challenges and improve diversity; however, the fact that seven of the ten trials [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] had proportionally lower enrollment of Black and Hispanic populations than their surrounding area suggests that additional challenges may remain. In truth, none of the trials addressed these issues by either commenting on their catchment area or the representativeness of trial enrollees relative to the composition of their cancer patient population. Furthermore, none addressed concerns related to limitations in their racial/ethnic data nor discussed other logistics that may encourage trial participation in these groups (e.g., inclusion of language-appropriate materials, use of bilingual study personnel). In fact, one trial [22] did not include details regarding their geographical region.

Adequate match between the target patient population and enrollment/accrual is another feature that is central to ensuring an intervention reaches the population it intends to treat. Although some trials maintain highly selective inclusion criteria to reduce heterogeneity, this approach risks excluding populations in most need of treatment. Encouragingly, most of our eligible trials had broad inclusion criteria, which should have enhanced enrollment of Black and Hispanic smokers. In fact, all but three trials (Browning [24], Ruebush [29], Krebs [26]) used fairly flexible criteria for smoking status, which should have provided opportunities for Black and Hispanic patients, commonly light and intermittent smokers, to enroll. All trials in this review also included cancers that were most prevalent in these two populations [38]. Yet, in spite of these broad criteria, enrollment rates for these two racial/ethnic groups remained surprisingly low. It is possible that Black and Hispanic smokers were differentially screened out in six of the studies due to concerns commonly noted in these two groups, including being sicker (i.e., advanced diagnoses, additional comorbidities) [22, 23, 26, 27], speaking a language other than English [20,21,22, 25, 27], or endorsing psychopathology [22, 26, 27]. None of these trials examined racial/ethnic differences in trial eligibility and/or enrollment, making it difficult to ascertain if study entry criteria impeded their participation.

Additional trial-related factors that may limit the engagement of Black or Hispanic cancer patients includes the use of passive recruitment methods. Schnoll [21] relied exclusively on chart screening to identify participants, and Nair [28] omitted recruitment details altogether. Chart screening has its limitations, particularly given the evidence that race/ethnicity information is often missing or misclassified and smoking status not discussed or documented. Additionally, only Park referenced the use of non-English recruitment brochures or bilingual staff to assist with the recruitment of Spanish-speaking smokers [25].

The trials in this review also demonstrated gaps in the reporting and analysis of race. This finding is supported by Dickerson and colleagues [39] who found limited advances in the reporting of racial/ethnic analyses in cessation trials altogether. In fact, of the ten trials reviewed, only Gritz [20], Schnoll [22], and Park [25] investigated the influence of race/ethnicity among other predictors for one of their outcomes. Although low sample size and lack of sample diversity likely hindered further analyses, it is notable that only Schnoll [22] and Charlot [27] acknowledged these limitations.

Although this review is among the first to examine this question of racial/ethnic representation in smoking cessation trials for cancer patients, two groups who most at risk of are experiencing poorer smoking and cancer outcomes, several limitations are worthy of mention. Specifically, our findings are based on information drawn from 10 trials. Because we wanted to capture information that is readily available to the public, our findings reflect only information that is currently published. It is possible that other trials have been conducted with our population of interest; however, low sample sizes and publication bias (i.e., difficulty publishing null data) may have limited our access to these investigations. It is also important to note that the trials included in this review were not specifically targeting minority populations; as such, reporting of racial/ethnic variables, cultural adaptations, and related outreach efforts may have been beyond the scope of their study. Additionally, this review only included trials that took place within the USA. It is possible that trials examining these issues of race/ethnicity and smoking within cancer may have been conducted internationally.

Regardless of these limitations, given the burden of cancer and tobacco use in these two groups, there remains a need to demonstrate that tobacco treatment trials are equally effective across race and ethnicity. Efforts to address these concerns should begin at the point of tobacco trial design and extend to publication; for instance, investigators are called to design trials that account for racial/ethnic variables that may impact behavior and behavioral outcomes; expand eligibility criteria so as to maximize the inclusion of groups who would otherwise be excluded; use multimodal and culturally sensitive approaches to identify and recruit patients; engage community health centers in recruitment efforts to broaden study reach; systematically document and report reasons for trial refusal and ineligibility; and collect, report, and examine, at a preliminary level, the predictive value of racial/ethnic variables on outcomes (while acknowledging sample size limitations). In return, funding agencies and peer-reviewed journals have a shared responsibility in addressing these disparities by requiring funded trials to integrate these standards into their work prior to funding and/or publication. Lastly, the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) and corresponding ethics committees (IRBs) are urged to support the diversification of trial accrual by adopting policies that balance the desire to uphold patient safety and confidentiality with the need to embrace alternate, more culturally sensitive approaches that accommodate the distinctive needs of these two under-represented groups (see Table 4 for a summary of recommendations).

In conclusion, there are a dearth of trials that investigate the reach and effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments for Black and Hispanic patients with cancer. The results of this review suggest that existing trials do not address important gaps in the care of these populations. Given the health risk associated with continued tobacco use following a cancer diagnosis, and the relative challenges Black and Hispanic cancer patients face with tobacco and cancer treatment, there is a critical need for researchers, academic institutions, and funding agencies to increase their efforts to engage these two populations in tobacco trials.

References

National Cancer Institute. Cancer health disparities. 2018. https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/crchd/cancer-health-disparities-fact-sheet#q4. Accessed May 5, 2017.

Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Miller KD, Goding-Sauer A, Jemal A, Pinheiro PS, et al. ACS report. Cancer remains leading cause of death in U.S. Hispanics. Oncol Times. 2015;37(20):30–1.

Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Miller KD, et al. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:457–80.

Park ER, Japuntich SJ, Traeger L, Cannon S, Pajolek H. Disparities between Blacks and Whites in tobacco and lung cancer treatment. Oncologist. 2011;16(10):1428–34.

de Dios MA, Anderson BJ, Stanton C, Audet DA, Stein M. Project impact: a pharmacotherapy pilot trial investigating the abstinence and treatment adherence of Latino light smokers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43(3):322–30.

Kumar P, Gareen IF, Lathan C, et al. Community outreach racial differences in tobacco cessation and treatment usage after lung screening: an examination of the national lung screening trial. Oncologist. 2016;21(1):40–9.

Houston TK, Scarinci IC, Person SD, Greene PG. Patient smoking cessation advice by health care providers: the role of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and health. Am J Public Health. 2005;9595(6):1056–61.

Cokkinides VE, Halpern MT, Barbeau EM, Ward E, Thun MJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in smoking-cessation interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(5):404–12.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf. Printed with corrections, January 2014. Accessed January 1, 2019.

Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569.

Danson SJ, Rowland C, Rowe R, et al. The relationship between smoking and quality of life in advanced lung cancer patients: a prospective longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(4):1507–16.

Islami F, Sauer A, Miller KD, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):31–54.

Park ER, Japuntich SJ, Rigotti NA, et al. A snapshot of smokers after lung and colorectal cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2012;118(12):3153–64.

Garces YI, Yang P, Parkinson J, et al. The relationship between cigarette smoking and quality of life after lung cancer diagnosis. Chest. 2004;126(6):1733–41.

Chen MS, Lara PN, Dang JHT, Paterniti DA, Kelly K. Twenty years post-NIH Revitalization Act: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT): laying the groundwork for improving minority clinical trial accrual. Cancer. 2014;120(S7):1091–6.

Hamel LM, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Heath E, Gwede CK, Eggly S. Barriers to clinical trial enrollment in racial and ethnic minority patients with cancer. Cancer Control. 2016;23(4):327–37.

Denicoff AM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Grubbs SS, Bruinooge SS, Comis RL, Devine P, et al. The National Cancer Institute-American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer Trial Accrual Symposium: Summary and Recommendations. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(6):267–27618.

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group [National Heart Lung and Blood Institute web site]. 2014. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/before-after. Accessed January 2016.

USDHHS. Study Quality Assessment Tools. (Maryland, 2017). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Gritz ER, Carr CR, Rapkin D, et al. Predictors of long-term smoking cessation in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkets Prev. 1993;2:261–70.

Schnoll RA, Rothman RL, Wielt DB. A randomized pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus basic health education for smoking cessation among cancer patinets. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(1):1–11.

Schnoll RA, Martinez E, Tatum KL, et al. A bupropion smoking cessation clinical trial for cancer patinets. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:811–20.

Schnoll RA, Zhang B, Rue M, et al. Brief physician-initiated quit-smoking strategies for clinical oncology settings: a trial coordinated by the eastern cooperative oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(2):355–65.

Browning KK, Ahijevych KL, Ross P, Wewers ME. Implementing the agency for health care policy and research’s smoking cessation guideline in a lung cancer surgery clinic. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27(8):1248–53.

Park ER, Perez GK, Regan S, et al. Effect of sustained smoking cessation counseling and provision of medication vs shorter-term counseling and medication advice on smoking abstinence in patients recently diagnosed with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1406–18. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.14581.

Krebs P, Burkhalter J, Fiske J, et al. The QuitIT coping skills game for promoting tobacco cessation among smokers diagnosed with cancer: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(1):e10071. https://doi.org/10.2196/10071. Published 2019 Jan 10.

Nair B, Safar A, Garrison W, Sherman A, Mehta P. Smoking cessation among patients in a cancer clinic: evaluation of a novel, motivational stop-smoking pocket calendar. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24:210–1.

Charlot M, D’Amico S, Luo M, Gemei A, Kathuria H, Gardiner P. Feasibility and acceptability of mindfulness-based group visits for smoking cessation in low-socioeconomic status and minority smokers with cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(7):762–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2019.0016.

Ruebush E, Mitra S, Meyer C, Sisler L, Goldstein AO. Using a family systems approach to treat tobacco use among cancer patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2050. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062050. Published 2020 Mar 19.

Gritz ER, Carr CR, Rapkin DA, Chang C, Beumer J, Ward PH. A smoking cessation intervention for head and neck cancer patients: trial design, patient accrual, and characteristics. Cancer Epide-Miol Biomark Prey. 1991;1:67–73.

Molina Y, Silva A, Rauscher GH. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to a breast cancer diagnosis: the mediating effects of health care facility factors. Med Care. 2015;53(10):872–8.

Ibraheem A, Polite B. Improving the accrual of racial and ethnic minority patients in clinical trials. Time to Raise the Stakes. Cancer. 2017;123(24):4752–6.

Taylor H, Leitman R. Misconceptions and lack of awareness greatly reduce recruitment for cancer clinical trials. Harris Interact: Health Care News. 2001;3:1–3.

Roberson NL. Clinical trial participation: viewpoints from racial/ethnic groups. Cancer. 1994;74(S9):2687–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9+%3c2687::aid-cncr2820741817%3e3.0.co;2-b.

Saluja S, McCormick D, Cousineau MR, Morrison J, Shue L, Joyner K, Hochman M. Barriers to primary care after the affordable care act: a qualitative study of Los Angeles Safety-Net patients’ experiences. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):423–30.

Galsky MD, Stensland KD, McBride RB, Latif A, Moshier E, Oh WK, Wisnivesky J. Geographic accessibility to clinical trials for advanced cancer in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;1745(2):293–5.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2019. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2019.

“USCS Data Visualizations - CDC.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/#/RaceEthnicity/.

Dickerson DL, Leeman RF, Mazure CM, O’Malley S. The inclusion of women and minorities in smoking cessation clinical trials: a systematic review. Am J Addict. 2009;18(1):21–8.

Bleich SN, Findling MG, Casey LS, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, SteelFisher GK, Sayde JM, Miller C. Discrimination in the United States: experiences of black Americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(Suppl 2):1399–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13220.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute: 3R01CA166147–02S1 (Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research). Giselle Katiria Perez, PhD is supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (K07 CA211955, GKP). Elyse R. Park is supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (K24CA197382, ERP). Dr. Ostroff’s work is supported in part by MSK CCSG (P30 CA008748-52S1). Dr. Park receives royalties from her contributions to UpToDate. No other authors have additional financial relationships to report. All of my co-authors approve of the manuscript and have contributed sufficiently to this project to warrant their inclusion as authors. No other individuals outside of the authors noted have contributed to this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Giselle Perez conceived the study, approach, and led the systematic review effort. Additionally, she led the writing. Julia Rabin, Nicole Strauss, and Megha Tandon were intimately involved in the analyses. They reviewed/coded all identified articles and prepared all tables/charts. Lisa Philpotts, a librarian with expertise in preparing systematic reviews, worked closely to guide us through the systematic review process as well as pulling articles meeting our eligibility criteria. Kelly Irwin, an expert in disparities research, offered insight into our analyses and interpretation of findings; additionally, she contributed to some of the writing. Jamie Ostroff and Elyse Park are senior mentors who are experts in tobacco treatment and cancer survivorship. Their NCI-funded R01 (Park and Ostroff- co-PIs) served as the impetus for this work, and the supplement to their R01 funded a portion of these efforts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent

This manuscript presents results from a systematic review of the literature on tobacco treatment and cancer survivorship. Human subjects were not involved, and thus IRB approval is not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perez, G.K., Rabin, J.T., Tandon, M. et al. Do Tobacco Treatment Trials Address Disparities in Smoking Outcomes Among Black and Hispanic Cancer Patients? A Systematic Review of Smoking Cessation Interventions for Black and Hispanic Patients Diagnosed with Cancer. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11, 2390–2406 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01705-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01705-3