Abstract

Hispanics in the USA, particularly those of Caribbean descent, experience high levels of diet-related diseases and dietary risk factors. Restaurants are an increasingly important yet understudied source of food and may present opportunities to positively influence urban food environments. We sought to explore food environments further, by examining the association between neighborhood characteristics and restaurant consumer nutrition environments within New York City’s Hispanic Caribbean (HC) restaurant environments. We applied an adapted version of the Nutrition Environment Measurements Survey for Restaurants (NEMS-R) to evaluate a random sample of HC restaurants (n=89). NEMS-HCR scores (continuous and categorized as low, medium, and high based on data distribution) were examined against area sociodemographic characteristics using bivariate and logistic regression analysis. HC restaurants located in Hispanic geographic enclaves had a higher proportion of fried menu items (p<0.01) but presented fewer environmental barriers to healthy eating, compared with those in areas with lower Hispanic concentrations. No significant differences in NEMS-R scores were found by other neighborhood characteristics. Size was the only significant factor predicting high NEMS-HCR scores, where small restaurants were less likely to have scores in the high category (NEMS-HCR score>6), compared with their medium (aOR: 6.6, 95% CI: 1.8–24.6) and large counterparts (aOR: 5.6, 95% CI: 1.5–21.4). This research is the first to examine the association between restaurant location and consumer nutrition environments, providing information to contribute to future interventions and policies seeking to improve urban food environments in communities disproportionately affected by diet-related conditions, as in the case of HC communities in New York City.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dietary factors are one of the leading causes of preventable death and disability [1]. In the USA, Hispanics have a higher burden of cardiovascular disease and other diet-related conditions, compared to non-Hispanic whites [2]. These disparities are further exacerbated when examining specific Hispanic communities. For instance, the multicenter US-based Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos cohort study suggest that, compared with other Hispanic groups, Dominicans and Puerto Ricans have higher rates of obesity and diabetes [3, 4] and lower consumption of vegetables and whole grains [5]. Moreover, research concerning dietary patterns among Hispanic Caribbean (HC) communities shows an overreliance on simple starches (white rice, plantains, and root crops), fried foods, and animal proteins, along with low consumption of leafy greens and other vegetables [6].

Most public health research and interventions addressing diet-related conditions focus on individual eating behaviors. While food environments are key in supporting and encouraging healthy food choices [7], less is known about the influence of food environments, especially among racial and ethnic minority communities. Food environments include the community and the consumer food environment. Community food environments reflect mostly food access, or the proximity, density, and variety of food outlets. Research examining community food environments show that low socioeconomic indicators are associated with decreased access to grocery stores (a marker of healthy food access) and increased access to fast-food outlets (a marker for unhealthy food access) [8]. The consumer nutrition environment, on the other hand, encompasses key factors influencing food choice once a consumer has selected a given food outlet [9]. These include, for instance, the availability of healthy options and their price, promotion, and placement [10].

Restaurants are an understudied part of the community food environment. Their role is important, as the consumption of foods away from home (FAFH) has been increasing in the past decades, accounting for approximately 34% of caloric intake in US households. On average, adults consume FAFH five times a week—a statistic not significantly different across racial groups [11]. In concordance with the average US household, Hispanics consume foods away from home frequently, for to-go and leisure family eating [12]. This is notable because research suggests that the consumption of FAFH is associated with increased intakes of saturated fat and sodium, negatively affecting health outcomes [13, 14]. Most of this existing research and resulting interventions in restaurants focus on fast-food or corporate establishments [15]. Moreover, few studies have examined the consumer nutrition environment in restaurants and the relationship with neighborhood-level characteristics. A review by Larson et al (2009) noted that restaurants in higher-income areas have been shown to have greater availability of healthy offerings, including salads, fruits, and whole grains [16]. When examining differences by racial and ethnic area makeup, research has focused on children and adolescent populations. For example, Dubreck et al 2019 examined the association between visible minority residents and the healthfulness of children’s consumer food environments in neighborhoods in Canada and the USA. Their findings suggest a negative correlation between the visible minority population in the area and restaurant healthfulness in the USA, while the inverse was found in Canada [17]. The US-based disparities by minority population have been echoed in other research addressing fast-food proximity to schools by area racial composition [16, 18]. To our knowledge, no studies have explicitly examined the consumer nutrition environments of ethnic restaurants by area socioeconomic characteristics.

Research concerning urban Hispanic enclaves argues that these areas are associated with lower consumption of high fat/processed foods and healthier food environments [19, 20]. Some authors have argued that this association may be due to enclave food businesses catering to the assumed healthier food demands of recent arrivals [19]. However, research is lacking in characterizing the actual contribution of ethnic-identified restaurants to the community food environment in Hispanic enclaves. This study aims to address this gap. We examined the association between neighborhood characteristics and the healthfulness of the consumer nutrition environment of restaurants serving HC cuisine in New York City (NYC). The city has the largest concentration of Hispanics in the USA, with Puerto Ricans and Dominicans being the dominant groups (30% and 28% of the NYC Hispanic population, respectively) [21]. HC communities have a historic presence in the city, resulting in the establishment of enduring enclave areas. Yet, HC restaurants are not confined within these enclaves, as they are spread across most of the city, providing opportunities to compare consumer environment healthfulness within HC restaurants by area characteristics. The insights presented through this analysis address a gap in the literature, examining the contribution of ethnic restaurants to the community food environment that ultimately influence food choices and resulting diet-related outcomes. Hence, the results can inform the design of interventions and policies to address restaurants as key institutions within community food environments, with the potential to positively affect persisting diet-related disparities among racial and ethnic minorities.

Methods

Restaurant Sampling and Assessment

Our sampling frame consisted of a list of all restaurants serving HC cuisines in New York City. The list was developed using Yelp, a popular restaurant review platform, which allows the identification of restaurants by specific cuisine served. The restaurant was included if it was identified as serving primarily Dominican, Cuban, and/or Puerto Rican cuisine (the conventional definition of HC communities) [22] and if it was located within the city’s five boroughs. The search yielded a total 183 restaurants, from which we selected a random sample representing approximating half of the total universe. Data were collected in June to August 2019, using an adapted version of the Nutrition Environments Measurement Survey for Restaurants (NEMS-R). The tool has been validated and widely used to examine the consumer nutrition environment of restaurants based on the availability of healthy options and their price, promotion, and placement [10]. The tool has three main dimensions: food availability (e.g., healthy main dish salads, whole grains, fruits), barriers to healthy eating (e.g., “all you can eat” promotions), and facilitators for healthy eating (e.g., menu highlights of healthy options). We expanded the tool based on previous research within HC communities and dietary patterns favorable to cardiovascular health [23,24,25,26]. These adaptations included the assessment of options classified as non-fried, non-fried seafood options, and vegetarian options and the provision of salt shakers at the table. The assessment was conducted by two trained research assistants (RAs), and it included an on-site observation and an off-site menu assessment. Inter-rater reliability was assessed early in the process, through duplicate assessments of 10% of the sample (n=8) [10], yielding good to excellent inter-rater agreement (mean=86.2%), including the total calculated score [23]. Data quality was monitored via weekly meetings, where conflicts regarding menu interpretation were discussed. Upon the completion of the field data collection, each completed assessment was cross-checked for accuracy by a second assessor before data entry, and entered records were checked for accuracy prior to analysis.

The total score of the adapted NEMS-R (NEMS-HCR) has the potential to range of –7 to 22, where higher scores denote healthier consumer nutrition environments. As the score has not been divided into meaningful evidence-based categories [10], we used natural breaks (also known as “Jenks”) to categorize the consumer nutrition environment scores in HC restaurants into three categories (low, medium, high) to be able to compare restaurants [17]. This approach was used, as opposed to the more commonly used tertiles. While tertiles use the count of observations to create evenly distributed groups, natural breaks use the data distribution to create groupings that minimize variance within grouped cases and maximize differences between the resulting groups [27].

Neighborhood Characteristics

All 89 restaurants addresses were geocoded using the NYC Address Points dataset from the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications [28]. The addresses were verified using Google Maps.

We used the NYC Department of City Planning street layer dataset to create a service area for each restaurant using ArcGIS 10.5.1. We delineated local neighborhoods around each restaurant as the 800-meter street network buffer that radiates in all walking directions from each restaurant, since 800 meters represent the approximate distance a person could walk in 10–15 minutes. The distance was selected following approaches followed in other food access research [17, 29]. This buffering technique took into consideration the actual street network available for traveling by foot when calculating buffer distances, rather than just straight-line Euclidean distances. Within each buffer, we aggregated census tract (CT)–level sociodemographic characteristics from the 2016 and 2018 American Community Surveys (ACS). In order to get more accurate estimates of sociodemographic characteristics within each buffer, we employed a Cadastral-based Expert Dasymetric Systems (CEDS) [30], whereby data from each CT were weighted by the estimated proportion of the CT population that resided within each buffer, based on tax lot-level data in the MapPLUTO database [31]. The CT boundaries were derived from the 2018 state-based Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing (TIGER)/Line Shapefile.

After allocating the proportion of each CT population that lies within each buffer, demographic variables were gathered across CTs within each buffer. Areas were classified as Hispanic enclaves if the proportion of Hispanics was more than 50%, following commonly used distribution-based classifications [19]. For economic variables, we computed the mean rent and median value of median household income across CTs in a buffer. Since poverty variables were not available in the 2018 ACS dataset, we obtained poverty data for adults 25 years of age or older from the 2016 ACS dataset, assuming that the prevalence of poverty level did not significantly change between 2016 and 2018.

To assess the potential influence of gentrification, we utilized an index that summarized the relative change of key socioeconomic and demographic variables from the years 2000–2016 for all NYC census tracts (under review). This index specifically integrated the relative change of (1) the proportion of total population that was non-Hispanic white, (2) proportion of population over 24 years of age with at least a 4-year college degree, (3) proportion of total population that was 20–34 years old, (4) median family income, and (5) median gross rent and is positively associated with rising inflation-adjusted residential property value [32]. We evaluated the potential association with this gentrification index as a continuous variable.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA IC11 (College Station, TX). We applied bivariate analysis (Student’s independent sample t-tests or chi-squared tests, as appropriate) to examine differences in restaurant and neighborhood characteristics and NEMS-HCR components and total scores, by area Hispanic majority classification. The results were used to develop a logistic regression model to examine the association between restaurants having a high NEMS-HCR score (versus “low” and “medium” categories), as defined by data distribution (as described above), and Hispanic enclave location, adjusting for restaurant size (small, medium, or large based on tertile distribution of number of seats from seating capacity or visual assessment) and area gentrification index (continuous variable), as key variables identified during the bivariate analysis.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The 89 restaurants included in the study were almost evenly split by type (sit-down vs. counter-style), with more than half serving primarily Dominican cuisine. Close to half of the restaurants (46%) were located in areas classified as Hispanic enclaves (46%). Restaurants located in Hispanic enclaves were not significantly different than their counterparts when compared by type (counter-style versus waited service), midpoint entrée price, or size. Only cuisine was different. Most Cuban restaurants (85%) were located outside Hispanic enclave areas, whereas most Puerto Rican restaurants (71%) were located in Hispanic enclave areas. Dominican restaurants were more evenly split, but with more than half (55%) located in enclave areas (p<0.01). Significant differences were found according to area sociodemographic characteristics, where restaurants located in Hispanic enclave areas were also associated with areas of lower median household income, median rent, and educational attainment and a higher percentage of the population classified as poor (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Consumer Environment in HC Restaurants

No restaurant had entrées classified as healthy, according to NEMS-R criteria, which classifies dishes as healthy if menus labeled these as “light” or “healthy” or if they meet a specified nutritional criterion, where the assessment depended on the provision of nutrition information on the menu (not present in the sample, Table 2). Very few (almost none) offered whole grains or fruit. Most of the restaurants offered vegetarian main dishes and non-fried, non-starch sides (e.g., side salad, steamed/grilled vegetables) and healthy main dish salads. Slightly more than half of the restaurants had menus with a large proportion of non-fried entrées and non-fried seafood. When comparing restaurants by Hispanic enclave location, only the proportion of non-fried items on menus was significantly different, being lower in restaurants located in Hispanic enclave areas (p<0.01) (Table 2).

The assessment revealed a general lack of environmental facilitators and barriers to healthy eating, as identified in the NEMS-R. Regarding facilitators, a few restaurants offered reduced-size portions, pricing favoring comparable non-fried entrées, or highlighted healthier menu options (e.g., having images on the menu of healthier dishes, such as grilled seafood and non-fried sides). Regarding barriers, the most common barrier was the presence of salt shakers on tables (assessed in occupied and empty tables), with few restaurants presenting other barriers, such as encouraging unhealthy eating (e.g., via menus showcasing mainly fried dishes) or encouraging large portions (e.g., offering to double the portion of chicken for a relatively low added cost). No restaurants presented other pre-specified barriers included in the evaluation, such as having “all you can eat” offers, charging for sharing an entrée, or discouraging healthy requests (item substitution). No significant differences in facilitators or barriers were found by location, with the exception of salt shakers, which were more prominent outside of Hispanic enclaves (p<0.01) (Table 2).

Restaurant Consumer Nutrition Environment by Neighborhood Characteristics

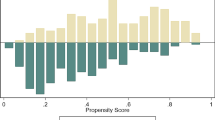

Restaurants locations and their respective neighborhood street network buffer zones are mapped in Figure 1, symbolized according to NEMS-HCR score category and the percent of the population in each buffer who are of Hispanic ethnicity. The mean NEMS-HCR score was 4.52, and the score in the sample ranged from 0 to 9. No significant differences in mean score were found by location. Based on the score distribution, a significant proportion of restaurants (46%) fell in the medium category, with scores between 3 and 5, followed by those in the high category (35%) with scores 6 to 9, and the rest (19%) fell within the low category with scores between 0 and 2 (Table 3). While restaurants in the low and medium NEMS-HCR score category were closely split by Hispanic enclave location, a higher percentage of restaurants with scores classified as high (and hence, relative healthier nutrition environments) was located outside of Hispanic enclave areas (Table 3, Figure 1). However, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.13).

The logistic regression analyses further showed the lack of significant association between the NEMS-HCR score and restaurant location within an ethnic enclave (Table 4). The only factor significantly associated with the odds of NEMS-HCR in the high category was restaurant size. Compared with small restaurants, medium and large restaurants were more likely to have NEMS-HCR scores in the high category (adjusted ORs = 6.6, 95% CI = 1.8–24.6 and adjusted ORs = 5.6, 95% CI 1.5–21.4 for medium and large restaurants, respectively). Neighborhood gentrification was not significantly associated with NEMS-HCR in the model.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present analysis is the first to examine the association between consumer food environment in HC restaurants and neighborhood characteristics. The few studies that have examined restaurants adjusting for neighborhood characteristics showed that low area income and high proportion of minority populations were significantly associated with lower healthy food availability [16, 17, 19, 20]. Our research did not find significant differences in the healthfulness of the consumer food environment in HC restaurants by area Hispanic composition, as measured by the NEMS-R. The main difference found was the higher prevalence of fried foods within restaurants located in Hispanic enclaves, compared to those in areas with lower HC concentrations. The healthfulness of the restaurant environments was also not associated with other neighborhood socioeconomic variables, such poverty, median income, and educational attainment. In these regards, our findings differ from prior research showcasing associations between area characteristics and the healthfulness of food establishments [16, 17, 19]. This underscores the need to examine ethnic restaurants within urban food environments and enclave communities.

Our randomly selected sample of HC restaurants was distributed across the city (with the exception of Staten Island), not just in Hispanic enclaves. We expected to find differences, assuming restaurant owners would seek to accommodate to neighborhood demographics. Healthy foods, such as whole grain and vegetable-forward offerings, are becoming popular and are associated with wealthier and whiter demographics [33]. Gentrification is changing the ethnic makeup of traditional Hispanic enclaves in NYC [34,35,36]. As wealthier residents move into Hispanic enclaves, they bring a potential increase demand for healthier offerings, as research has documented that healthful eating behaviors can be used as a mark of social distinction among higher social classes [37, 38]. Yet, contrary to our assumption that restaurants would adjust to neighborhood demographic characteristics, we did not find significant differences in consumer nutrition environment healthfulness nor in most of the NEMS-HCR items, with the exception of fried foods (a component not assessed in the original NEMS-R), which were more prevalent in restaurants located in Hispanic enclaves. The lack of expected associations denotes the importance of examining restaurants serving ethnic cuisines, as the case of the HC restaurants in this study. In these restaurants, menus are designed to accommodate the owner’s or chef’s ideas around cuisine authenticity and which dishes will sell within the mainstream society perceptions of the given cuisine. Research suggests that NYC HC restaurant owners and cooks/chefs view HC cuisines as largely unhealthy but where certain preparation methods (i.e., frying foods) and menu offerings are seen as key to conveying authenticity [26, 39,40,41,42]. Similarly, healthier offerings seen as part of the cuisines (i.e., non-starchy vegetables and brown rice) may potentially be left out of menu to preserve authenticity [26]. These notions, as well as lack of culinary training found in previous research [26], may be barriers to adjusting to menus and consumer environments with neighborhood transitions, potentially explaining the lack of association between neighborhood characteristics and the HC restaurant consumer nutrition environments. Longitudinal research to capture transitions in restaurant menus is needed to provide further insights into the role of gentrification and other area transitions, as part of the growing body of work examining the impact of gentrification on health [43].

Our analysis revealed that restaurant size was the only significant factor associated with healthier consumer food environments in HC restaurants, where large- and medium-sized restaurants were more likely to have high NEMS-HCR scores, compared with smaller ones. Smaller restaurants may present physical environment limitations that could influence food offerings and spatial cues to motivate healthy eating. These may include a limited kitchen and storage space, which could make the storage and preparation of healthier offerings more difficult. Kitchen space may limit the variety of foods a kitchen can offer. Larger restaurants involve larger capital investments, including higher lease and maintenance costs. These increased investments may motivate restaurants to seek to appeal to a larger audience to increase profit opportunities. In doing so, the variety of offerings may include offerings that satisfy health-conscious customers.

Restaurants, as businesses, are driven by the need for profit. This is especially important for ethnic restaurants trying to survive in a place like NYC, where they face increasing rent and ongoing displacement due to gentrification, as well as the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic [44,45,46]. This makes the understanding of the connection between neighborhood factors and restaurant consumer environments particularly important. Such information will allow for more targeted policies and programs to help these fragile businesses manage neighborhood economic transitions while also establishing fruitful collaborations for the restaurants to be an active part in improving the community’s healthy food availability. Such collaborations can include interventions that provide economic incentives tied to healthier food offerings among independently owned restaurants in areas with high rates of diet-related health disparities. These new initiatives can leverage lessons learned from health promotion strategies in bodegas (corner stores) or strategies that incentivized healthy food vendors in underserved urban areas [47, 48].

Our research was limited by the use of secondary data to examine area characteristics. Neighborhood variables were obtained from the American Community Survey, which is subject to sampling error; however, any error is likely to be systematic across the census tracts used in this study. The use of administrative data for neighborhood characteristics only allowed us to focus on characteristics of residents within the buffer zones. Therefore, we were unable to capture all potential customers of the selected restaurants, especially in restaurants located outside residential areas catering to work lunch customers, for example. Last but not least, our research was unable to collect data on the customer base of the restaurants nor the customer consumer experience and behaviors within the restaurants. That is, our study focused on the choices available at the restaurants, but we did not examine which choices are actually being consumed or by whom. Therefore, no conclusions could be drawn about actual consumer diet or how consumers interfaced with specific restaurants. Future studies can provide further insights by examining which choices are being consumed and potential differences by socioeconomic characteristics, including Hispanic ethnicity.

These methodological limitations highlight above are inherent to food environment research studies, showcasing the need to further advance our understanding of commercial food establishments, to really understand the systematic forces driving supply and demand, linking neighborhood characteristics to the consumer food environments within restaurants. This includes the influence of other competing establishments, such as neighboring ethnic restaurants and street food vendors, serving as important meal purveyors in large, urban, global cities, like New York [49].

Ethnic restaurants have not been the focal point of consumer food environment research despite the important social and economic role these establishments play in their communities. These establishments can serve as a novel vehicle to promote healthful eating practices among residents in these communities that disproportionately suffer from diet-related chronic conditions. More research is needed to further understand the barriers and motivating factors of independent ethnic restaurants regarding the promotion of healthier eating behaviors.

Availability of Data and Material

Available upon request

Code Availability

Available upon request

References

González HM, Tarraf W, Rodríguez CJ, Gallo LC, Sacco RL, Talavera GA, et al. Cardiovascular health among diverse Hispanics/Latinos: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) results. Am Heart J. 2016;176:134–44.

NHLBI. The science: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). [cited 2018 21, 2018]; Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/science/hispanic-community-health-studystudy-latinos-hchssol.

Heiss G, Snyder ML, Teng Y, Schneiderman N, Llabre MM, Cowie C, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Hispanics/Latinos of diverse background: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2391–9.

Schneiderman N, Llabre M, Cowie CC, Barnhart J, Carnethon M, Gallo LC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from diverse backgrounds: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2233–9.

Siega-Riz AM, Sotres-Alvarez D, Ayala GX, Ginsberg M, Himes JH, Liu K, et al. Food-group and nutrient-density intakes by Hispanic and Latino backgrounds in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1487–98.

Fuster M. “We like fried things”: negotiating health and taste among Hispanic Caribbean communities in New York City. Ecol Food Nutr. 2017;56(2):124–38.

Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–72.

Leia M, et al. Measuring the food environment: from theory to planning practice. J Agric Food Sys Comm Dev. 2011;2(1).

Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19:330–3.

Saelens BE, et al. Nutrition Environment Measures Study in Restaurants (NEMS-R): development and evaluation. Am J Prev Med. 2001;32(4):273–81.

Saksena MJ, et al., America’s eating habits: food away from home, in Economic Research Bulletin, M.J. Saksena, A.M. Okrent, and K.S. Hamrick, Editors. 2018, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC.

Lee Yohn, D. The many faces of the Hispanic market. QSR, 2014.

Jiao J, Moudon AV, Kim SY, Hurvitz PM, Drewnowski A. Health implications of adults' eating at and living near fast food or quick service restaurants. Nutrition & Diabetes. 2015;5(7):e171.

Chum A, O'Campo P. Cross-sectional associations between residential environmental exposures and cardiovascular diseases. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:438.

Fuster M, Handley MA, Alam T, Fullington LA, Elbel B, Ray K, et al. Facilitating healthier eating at restaurants: a multidisciplinary scoping review comparing strategies, barriers, motivators, and outcomes by testaurant type and initiator. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1479.

Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74–81.e10.

DuBreck CM, Sadler RC, Arku G, Seabrook J, Gilliland J. A comparative analysis of the restaurant consumer food environment in Rochester (NY, USA) and London (ON, Canada): assessing children's menus by neighbourhood socio-economic characteristics. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(9):1654–66.

Hilmers A, Hilmers DC, Dave J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1644–54.

Osypuk TL, et al. Are immigrant enclaves healthy places to live? The Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 1982), 2009;69(1):110–20.

Lee RE, Cubbin C. Neighborhood context and youth cardiovascular health behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):428–36.

Greer, S., et al., Health of Latinos in NYC. 2017, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. p. 32.

Duany J. Blurred borders: transnational migration between the Hispanic Caribbean and the United States. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 2011.

Fuster M, et al. Ethnic restaurant nutrition environments and cardiovascular health: examining Hispanic Caribbean restaurants in New York City. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(4).

Folsom AR, Shah AM, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, Alonso A, Avery CL, et al. American Heart Association's Life's Simple 7: avoiding heart failure and preserving cardiac structure and function. Am J Med. 2015;128(9):970–6 e2.

Fuster M, Between tradition and health: comparing community and expert perceptions of Hispanic Caribbean diets in NYC, in Experimental Biology / American Society for Nutrition Annual Meeting. 2017: Chicago, IL.

Fuster M, et al. Engaging ethnic restaurants to improve community nutrition environments: a qualitative study with Hispanic Caribbean restaurants in New York City. Ecol Food Nut. 2020:1–17.

Fisher WD. On grouping for maximum homogeneity. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(284):789–98.

DoITT NYC. Address Points. The City of New York: NYC OpenData; 2015.

Timperio AF, Ball K, Roberts R, Andrianopoulos N, Crawford DA. Children's takeaway and fast-food intakes: associations with the neighbourhood food environment. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(10):1960–4.

Maantay JA, Maroko AR, Herrmann C. Mapping population distribution in the urban environment: the Cadastral-based Expert Dasymetric System (CEDS). Cartogr Geogr Inf Sci. 2007;34(2):77–102.

DCP, BYTES of the BIG APPLE™ 2020, City of New York: Department of City Planning.

Johnson GD, et al., A small area index of gentrification, applied to New York City. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 2021. (accepted, forthcoming).

Anguelovski I. Healthy food stores, greenlining and food gentrification: contesting new forms of privilege, displacement and locally unwanted land uses in racially mixed neighborhoods. Int J Urban Reg Res. 2015;39(6):1209–30.

Hernández R, Sezgin U, Marrara S, When a neighborhood becomes a revolving door for Dominicans: rising housing costs in Washington Heights/Inwood and the declining presence of Dominicans. 2018, CUNY Dominican Studies Institute: New York City.

Freudenberg, N., et al., Eating in East Harlem: an assessment of changing foodscapes in community district 11, 2000-2015. 2016, CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy and New York City Food Policy Center at Hunter College: New York, NY.

Newman K, Wyly EK. The right to stay put, revisited: gentrification and resistance to displacement in New York City. Urban Stud. 2006;43(1):23–57.

Bourdieu P. Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1986.

Oude Groeniger J, van Lenthe FJ, Beenackers MA, Kamphuis CBM. Does social distinction contribute to socioeconomic inequalities in diet: the case of ‘superfoods’ consumption. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:40.

Barbas S. “I'll take chop suey”: restaurants as agents of culinary and cultural change. J Pop Cult. 2003;36(4):669.

Jochnowitz E, From khatchapuri to gefilte fish: dining out and spectacle in Russian Jewish New York, in The Restaurants Book: Ethnographies of where we eat, D. Berris and D. Sutton, Editors. 2007, Berg: New York. p. 115-132.

Ray K. The immigrant restaurateur and the American city: taste, toil, and the politics of inhabitation. Social Research. 2014;81:373–96.

Oum YR. Authenticity and representation: cuisines and identities in Korean-American diaspora. Postcolonial Studies. 2005;8(1):109–25.

Smith GS, Breakstone H, Dean LT, Thorpe RJ Jr. Impacts of gentrification on health in the US: a systematic review of the literature. J Urban Health. 2020;97(6):845–56.

Cohen N. Feeding or starving gentrification: the role of food policy. CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute: New York; 2018.

Goworowska, J., Gentrification, displacement and the ethnic neighborhood of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, in Department of Geography. 2008, Graduate School of the University of Oregon: Oregon.

Acevedo N Latino restaurant owners in New York City struggle to stay afloat amid coronavirus crisis. NBC News, 2020.

Dannefer R, et al. Healthy bodegas: increasing and promoting healthy foods at corner stores in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(10):27–31.

Leggat M, Kerker B, Nonas C, Marcus E. Pushing produce: the New York City Green Carts initiative. J Urban Health. 2012;89(6):937–8.

Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Patel AN, Gjonbalaj I, Elbel B, Schechter CB. Healthful and less-healthful foods and drinks from storefront and non-storefront businesses: implications for 'food deserts', 'food swamps' and food-source disparities. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(8):1428–39.

Funding

The research was supported by the NIH-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Award # K01HL147882) and the Professional Staff Congress-City University of New York (PSC-CUNY) Research Award Program (#62534-00 50). Additional funding support for TH was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006396). The funders had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. M.F. is the principal investigator and primary author, secured project funding, developed the project concept, supervised the data collection for the restaurant assessment, and conducted the analysis. H.K. collected and geocoded the neighborhood data and conducted the mapping. K.R., B.E., M.A.H., and T.K.H. advised on all aspects of the manuscript and contributed to the write-up and revisions of the manuscript. G.J. supervised the geocoding and mapping process, advised on the statistical analysis, and contributed to the manuscript write-up and revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study did not involve human subjects.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fuster, M., Kodali, H., Ray, K. et al. Area Characteristics and Consumer Nutrition Environments in Restaurants: an Examination of Hispanic Caribbean Restaurants in New York City. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 9, 1454–1463 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01083-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01083-8