Abstract

Maternal morbidity and mortality (MMM) is a significant problem in the USA, with about 700 maternal deaths every year and an estimated 50,000 “near misses.” Disparities in MMM by race are marked; black women are disproportionately affected. We use Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory to examine the root causes of racial disparities in MMM at the individual (microsystem), interpersonal (mesosystem), community (exosystem), and societal (macrosystem) levels of influence. This review discusses the interaction of these levels of influence on racial disparities related to MMM—covering preconception health, access to prenatal care, implicit bias among health care providers and its possible influence on obstetric care, “maternity care deserts,” and the need for quality improvement among black-serving hospitals. Relevant policies—parental leave, Medicaid coverage during pregnancy, and Medicaid expansion—are considered. We also apply the ecological systems theory to identify interventions that would most likely reduce disparities in MMM by race, such as revising the educational curricula of health care professionals, enhancing utilization of alternate prenatal care providers, and reforming Medicaid policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Defined as death “while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes” (Hoyert & Miniño, 2020), which excludes deaths from suicide, homicide, and overdose

Other factors relevant to MMM disparities that could be considered with the ecological systems theory include maternal age, education, and socioeconomic status (individual); intimate partner violence (interpersonal); pollution and toxins in the local environment (community); and mass incarceration and weathering (societal).

Notably, one of these bundles specifically addresses racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy-related deaths. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/index.html. Accessed 12 Mar 2020.

GBD 2015. Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–812.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD.Stat. https://stats.oecd.org. Accessed 12 Mar 2020.

Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Mayes N, Johnston E, et al. Vital signs: pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013–2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(18):423–9.

Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. Maternal mortality in the United States: changes in coding, publication, and data release, 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020;69(2):1–18.

Hoyert DL, Uddin SFG, Miniño AM. Evaluation of the pregnancy status checkbox on the identification of maternal deaths. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020;69(1):1–25.

Davis NL, Hoyert DL, Goodman DA, Hirai AH, Callaghan WM. Contribution of maternal age and pregnancy checkbox on maternal mortality ratios in the United States, 1978–2012. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):352.e1–7.

Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, Bateni ZH, Belfort MA, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, et al. Health care disparity and pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(4):707–12.

Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935–2007: substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed 9 Apr 2020.

Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths—United States, 2007–2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(35):762–5.

Tucker MJ, Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Hsia J. The black–white disparity in pregnancy-related mortality from 5 conditions: differences in prevalence and case-fatality rates. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):247–51.

Louis JM, Menard MK, Gee RE. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):690–4.

Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Zivin K, Terplan M, Mhyre JM, Dalton VK. Racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence of severe maternal morbidity in the United States, 2012–2015. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):1158–66.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe maternal morbidity in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html. Accessed 4 Mar 2020.

Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):335–43.

Braun L. Race, ethnicity, and health: can genetics explain disparities? Perspect Biol Med. 2002;45(2):159–74.

Nobles M. History counts: a comparative analysis of racial/color categorization in US and Brazilian censuses. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(11):1738–45.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):69–101.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States; Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, Weinstein JN, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Causes of pregnancy-related death in the United States: 2011–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#causeson. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Jain JA, Temming LA, D’Alton ME, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Tuuli M, Louis JM, et al. SMFM special report: putting the “M” back in MFM: reducing racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2):B9–17.

Härkönen U The Bronfenbrenner ecological systems theory of human development, Scientific Articles of V International Conference, pp. 1–17.

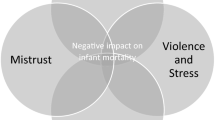

Alio AP, Richman AR, Clayton HB, Jeffers DF, Wathington DJ, Salihu HM. An ecological approach to understanding black–white disparities in perinatal mortality. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(4):557–66.

Loggins Clay S, Griffin M, Averhart W. Black/white disparities in pregnant women in the United States: an examination of risk factors associated with black/white racial identity. Health Soc Care Commun. 2018;26:654–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12565.

Robbins C, Boulet SL, Morgan I, D'Angelo DV, Zapata LB, Morrow B, et al. Disparities in preconception health indicators — behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013–2015, and pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2013–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):1–16.

Agrawal P. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States of America. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(3):135.

Yan J. The effects of prenatal care utilization on maternal health and health behaviors. Health Econ. 2017;26(8):1001–18.

Lu MC. Reducing maternal mortality in the United States. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1237–8.

Gadson A, Akpovi E, Mehta PK. Exploring the social determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(5):308–17.

Berchick E. Most uninsured were working-age adults. U.S. Census Bureau. September 12, 2018. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/09/who-are-the-uninsured.html. Accessed 5 March, 2020.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Changes in health coverage by race and ethnicity since the ACA, 2010–2018. 2020. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018. Accessed 9 Apr 2020.

McMorrow S, Kenney G. Despite progress under the ACA, many new mothers lack insurance coverage; 2018. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20180917.317923/full. Accessed 9 Apr 2020

Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid and CHIP income eligibility limits for pregnant women, 2003–2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-and-chip-income-eligibility-limits-for-pregnant-women/?activeTab=map¤tTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=january-2019&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22January%202019%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

National Conference of State Legislatures. Paid sick leave. 2020. https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/paid-sick-leave.aspx. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Davis D. Obstetric racism: the racial politics of pregnancy, labor, and birthing. Med Anthropol. 2019;38(7):560–73.

McLemore MR, Altman MR, Cooper N, Williams S, Rand L, Franck L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc Sci Med. 2018;201:127–35.

Roman LA, Raffo JE, Dertz K, Agee B, Evans D, Penninga K, et al. Understanding perspectives of African American Medicaid-insured women on the process of perinatal care: an opportunity for systems improvement. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(1):81–92.

Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Patient-reported communication quality and perceived discrimination in maternity care. Med Care. 2015;53(10):863–71.

Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Health care engagement and follow-up after perceived discrimination in maternity care. Med Care. 2017;55(9):830–3.

March of Dimes. Nowhere to go: maternity care deserts across the U.S. 2018. https://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/Nowhere_to_Go_Final.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Hansen A, Moloney M. Pregnancy-related mortality and severe maternal morbidity in rural Appalachia: established risks and the need to know more. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):3–8.

Kozhimannil KB, Hung P, Henning-Smith C, Casey MM, Prasad S. Association between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and birth outcomes in rural counties in the United States. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1239–47.

Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):122.e1–7.

Jou J, Kozhimannil KB, Abraham JM, Blewett LA, McGovern PM. Paid maternity leave in the United States: associations with maternal and infant health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216–25.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Parental leave systems. 2019. http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_1_Parental_leave_systems.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Access to paid and unpaid family leave in 2018. 2019. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2019/access-to-paid-and-unpaid-family-leave-in-2018.htm. Accessed 6 Mar 2020.

Zagorsky JL. Divergent trends in US maternity and paternity leave, 1994–2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):460–5.

Sakala C, Declercq ER, Turon JM, Corry MP. Listening to mothers in California: a population-based survey of women’s childbearing experiences. 2018. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ListeningMothersCAFullSurveyReport2018.pdf. Accessed 9 Apr 2020.

Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Moniz MH, Davis MM, Heisler M, Dalton VK. Disparities in chronic conditions among women hospitalized for delivery in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):1319–26.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Women’s health insurance coverage. 2020. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/womens-health-insurance-coverage-fact-sheet. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What happens during prenatal visits? https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/preconceptioncare/conditioninfo/prenatal-visits. Accessed 5 Mar 2020.

Green TL. Unpacking racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care use: the role of individual-, household-, and area-level characteristics. J Women's Health. 2018;27(9):1124–34.

Building U.S. Capacity to review and prevent maternal deaths. Report from nine maternal mortality review committees 2018. http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):e140–50.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Postpartum Toolkit. Racial disparities in maternal mortality in the United States: the postpartum period is a missed opportunity for action. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Toolkits-for-Health-Care-Providers/Postpartum-Toolkit/ppt-racial.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20190712T1725487399. Accessed 6 Mar 2020.

Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, The Ohio State University. Understanding implicit bias. 2015. http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/understanding-implicit-bias. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–10.

Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–8.

Attanasio LB, Hardeman RR. Declined care and discrimination during the childbirth hospitalization. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:270–7.

Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):77.

Roth LM, Henley MM. Unequal motherhood: racial–ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in cesarean sections in the United States. Soc Probl. 2012;59(2):207–27.

National Partnership for Women & Families. Black women’s maternal health: a multifaceted approach to addressing persistent and dire health disparities. 2018. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/health-care/maternity/black-womens-maternal-health-issue-brief.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 649. Racial and ethnic disparities in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e130–4.

ACOG Opinion Committee No. 729. Importance of social determinants of health and cultural awareness in the delivery of reproductive health care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e43–8.

HCUP Fast Stats. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Most common diagnoses for inpatient stays. 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/national/inpatientcommondiagnoses.jsp. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief, No 318. National Center for Health Statistics 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db318.pdf. Accessed 9 Apr 2020.

Kirby PB, Spetz J, Maiuro L, Scheffler RM. Changes in service availability in California hospitals, 1995 to 2002. J Healthc Manag. 2006;51(1):26–38.

The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina. 168 rural hospital closures: January 2005–present (119 since 2010). https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures. .

Hung P, Henning-Smith CE, Casey MM, Kozhimannil KB. Access to obstetric services in rural counties still declining, with 9 percent losing services, 2004-14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1663–71.

Kornelsen J, Stoll K, Grzybowski S. Stress and anxiety associated with lack of access to maternity services for rural parturient women. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(1):9–14.

Kornelsen J, Moola S, Grzybowski S. Does distance matter? Increased induction rates for rural women who have to travel for intrapartum care. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(1):21–7.

Maron DF. Maternal health care is disappearing in rural America. Sci Am 2017. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/maternal-health-care-is-disappearing-in-rural-america. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Kuklina E, Shilkrut A, Callaghan WM. Performance of racial and ethnic minority-serving hospitals on delivery-related indicators. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):647.e1–16.

Lorch SA, Martin AE, Ranade R, Srinivas SK, Grande D. Lessons for providers and hospitals from Philadelphia’s obstetric services closures and consolidations, 1997-2012. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(12):2162–9.

Howell EA, Zeitlin J. Improving hospital quality to reduce disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(5):266–72.

Nandi A, Jahagirdar D, Dimitris MC, Labrecque JA, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS, et al. The impact of parental and medical leave policies on socioeconomic and health outcomes in OECD countries: a systematic review of the empirical literature. Milbank Q. 2018;96(3):434–71.

U.S. Department of Labor. Family and Medical Leave Act. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

Hegewisch A, Hartmann H. The gender wage gap: 2018 earnings differences by race and ethnicity. Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2019. https://iwpr.org/publications/gender-wage-gap-2018. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid income eligibility limits for parents, 2002–2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-parents/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=january-2019&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22January%202019%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D. Accessed 9 Apr 2020.

Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018, P.l. No. 115–344. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1318/text.

Lu M. Statement before the Ways and Means Committee, U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, DC; 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enhancing Reviews and Surveillance to Eliminate Maternal Mortality (ERASE MM). https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/index.html. Accessed 12 Mar 2020.

Griffith JR. Is it time to abandon hospital accreditation? Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(1):30–6.

Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Patient safety bundles. https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/patient-safety-bundles/#link_tab-maternal. Accessed 12 Mar 2020.

Lyons M. New joint commission standards address rising maternal mortality in the US. The Joint Commission 2019. https://www.jointcommission.org/new_joint_commission_standards_address_rising_maternal_mortality_/#comments. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Clark SL, Christmas JT, Frye DR, Meyers JA, Perlin JB. Maternal mortality in the United States: predictability and the impact of protocols on fatal postcesarean pulmonary embolism and hypertension-related intracranial hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(1):32.e1–9.

Main EK, Cape V, Abreo A, Vasher J, Woods A, Carpenter A, et al. Reduction of severe maternal morbidity from hemorrhage using a state perinatal quality collaborative. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):298.e1–298.e11.

Obstetric Care Consensus No. 8. Summary: interpregnancy care. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):220–5.

Eliason E. Adoption of Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act is associated with lower rates of maternal mortality. 2019. https://academyhealth.confex.com/academyhealth/2019nhpc/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/29402. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Searing A, Cohen Ross D. Medicaid expansion fills gaps in maternal health coverage leading to healthier mothers and babies. Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families. 2019. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Maternal-Health-3a.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Access in brief: pregnant women and Medicaid. 2018. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Pregnant-Women-and-Medicaid.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60–76.

van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, Herrin J, et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: a medical student CHANGES study report. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1748–56.

Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(11):1773–8.

Spettel S, White MD. The portrayal of J. Marion Sims’ controversial surgical legacy. J Urol. 2011;185(6):2424–7.

Silver JK, Bean AC, Slocum C, Poorman JA, Tenforde A, Blauwet CA, et al. Physician workforce disparities and patient care: a narrative review. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):360–77.

Martin N. A larger role for midwives could improve deficient U.S. care for mothers and babies. ProPublica. 2018. https://www.propublica.org/article/midwives-study-maternal-neonatal-care. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

MacDorman MF, Singh GK. Midwifery care, social and medical risk factors, and birth outcomes in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(5):310–7.

Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Relationship between hospital-level percentage of midwife-attended births and obstetric procedure utilization. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2018;63(1):14–22.

Kozhimannil KB, Attanasio LB, Yang YT, Avery MD, Declercq E. Midwifery care and patient–provider communication in maternity decisions in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(7):1608–15.

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD004667.

Bey A, Brill A, Porchia-Albert C, Gradilla M, Strauss N. Advancing birth justice: community-based doula models as a standard of care for ending racial disparities. Ancient Song Doula Services 2019. https://blackmamasmatter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Advancing-Birth-Justice-CBD-Models-as-Std-of-Care-3-25-19.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Kozhimannil KB, Vogelsang CA, Hardeman RR, Prasad S. Disrupting the pathways of social determinants of health: doula support during pregnancy and childbirth. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(3):308–17.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Lori Whitten, PhD, in editing the manuscript and providing additional assistance with research. This work was performed as part of an NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health contract with Synergy Enterprises, Inc.

This manuscript was developed during research internship of Bani Saluja and Leah Richey, graduate students at the University of Maryland, under Dr. Noursi’s supervision. The authors are grateful to Janine Clayton, MD, Associate Director for Research on Women’s Health, NIH; Director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) for her support throughout the development of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Noursi, S., Saluja, B. & Richey, L. Using the Ecological Systems Theory to Understand Black/White Disparities in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8, 661–669 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00825-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00825-4