Abstract

Objectives

To examine disparities in use and access to different health care providers by community and individual race-ethnicity and to test provider supply as a potential mediator.

Data Sources

National secondary data from 2014 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 5-year estimates (2010–2014) from American Community Survey, and 2014 InfoUSA.

Study Design

Multiple logistic regression models examined the association of community and individual race-ethnicity with reported health care visits and access. Mediation analyses tested the role of provider supply.

Data Extraction Methods

Individual-level survey data were linked to race-ethnic composition and health business counts of the respondent’s primary care service area (PCSA).

Principal Findings

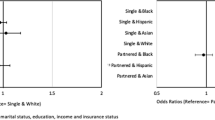

Minority PCSAs are significantly and independently associated with lower odds of having a visit to a physician assistant/nurse practitioner, dentist, or other health professionals and having a usual care provider (all p < 0.05). Few significant associations were observed for integrated PCSAs or for health provider supply. A modest mediation effect for provider supply was observed for travel time to usual care provider and visit to other health professionals.

Conclusions

Use of a range of health services is lower in minority communities and individuals. However, provider supply was not an important explanatory factor of these disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The 2014 national healthcare quality and disparities report (AHRQ Pub. No. 15-0007). Rockville, MD 2015.

Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary R. Residential segregation and disparities in health care services utilization. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):158–75.

Manuel JI. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in health care use and access. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1407–29.

Liao Y, Bang D, Cosgrove S, et al. Surveillance of health status in minority communities - racial and ethnic approaches to community health across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) Risk Factor Survey, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(6):1–44.

Manseau M, Case BG. Racial-ethnic disparities in outpatient mental health visits to U.S. physicians, 1993–2008. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:59–67.

Manski RJ, Brown E. Dental use, expenses, private dental coverage, and changes, 1996 and 2004 (MEPS Chartbook No.17). Rockville, MD 2007.

Zhang Y. Racial/ethnic disparity in utilization of general dental care services among US adults: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2012. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(4):565–72.

Gaskin DJ, Price A, Brandon DT, Laveist TA. Segregation and disparities in health services use. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):578–89.

Eisen CH, Bowie JV, Gaskin DJ, LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ. The contribution of social and environmental factors to race differences in dental services use. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):415–21.

Johnson AM, Johnson A, Hines RB, Bayakly R. The effects of residential segregation and neighborhood characteristics on surgery and survival in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25(5):750–8.

Ojinnaka CO, Luo W, Ory MG, McMaughan D, Bolin JN. Disparities in surgical treatment of early-stage breast cancer among female residents of Texas: the role of racial residential segregation. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(2):e43–52.

Luo H, Beckles G, Zhang X, Sotnikov S, Thompson T, Bardenheier B. The relationship between county-level contextual characteristics and use of diabetes care services. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(4):401–10.

Hayanga AJ, Kaiser HE, Sinha R, Berenholtz SM, Makary M, Chang D. Residential segregation and access to surgical care by minority populations in US counties. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(6):1017–22.

Rodriguez RA, Sen S, Mehta K, Moody-Ayers S, Bacchetti P, O’Hare AM. Geography matters: relationships among urban residential segregation, dialysis facilities, and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(7):493–501.

Kirby JB, Taliaferro G, Zuvekas SH. Explaining racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Med Care. 2006;44:I-64–72.

Dai D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010;16(5):1038–52.

Goodwin AJ, Nadig NR, McElligott JT, Simpson KN, Ford DW. Where you live matters: the impact of place of residence on severe sepsis incidence and mortality. Chest. 2016;150(4):829–36.

Pilkerton CS, Singh SS, Bias TK, Frisbee SJ. Healthcare resource availability and cardiovascular health in the USA. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e016758.

Gai Y, Gu NY. Relationship between local family physician supply and influenza vaccination after controlling for individual and neighborhood effects. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(5):500–5.

Cook BL, Doksum T, Chen CN, Carle A, Alegria M. The role of provider supply and organization in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:102–9.

Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Probst JC. More may be better: evidence of a negative relationship between physician supply and hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(4):1148–66.

Lin YH, Eberth JM, Probst JC. Ambulatory care-sensitive condition hospitalizations among medicare beneficiaries. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):493–501.

Baltrus P, Xu J, Immergluck L, Gaglioti A, Adesokan A, Rust G. Individual and county level predictors of asthma related emergency department visits among children on Medicaid: a multilevel approach. J Asthma. 2017;54(1):53–61.

Chi DL, Leroux B. County-level determinants of dental utilization for Medicaid-enrolled children with chronic conditions: how does place affect use? Health Place. 2012;18(6):1422–9.

Fingar KR, Smith MW, Davies S, McDonald KM, Stocks C, Raven MC. Medicaid dental coverage alone may not lower rates of dental emergency department visits. Health Aff. 2015;34(8):1349–57.

Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary RR. Residential segregation and the availability of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2353–76.

Chan KS, Gaskin DJ, McCleary RR, Thorpe RJ. Availability of health care provider offices and facilities in minority and integrated communities in the U.S. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(3):986–1000.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: survey background. 2019. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp. Accessed March 4, 2019.

Chodur GM, Shen Y, Kodish S, et al. Food environments around American Indian reservations: a mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161132.

Dubowitz T, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Eibner C, et al. The women’s health initiative: the food environment, neighborhood socioeconomic status, BMI, and blood pressure. Obesity. 2012;20(4):862–71.

Mazumdar S, Butler D, Bagheri N, et al. How useful are primary care service areas? Evaluating PCSAs as a tool for measuring primary care practitioner access. Appl Geogr. 2016;72:47–54.

Goodman DC, Mick SS, Bott D, et al. Primary care service areas: a new tool for the evaluation of primary care services. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:287–309.

Gaskin DJ, Thorpe RJ, McGinty EE, et al. Disparities in diabetes: the nexus of race, poverty and place. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:2147–55.

Office of Management and Budget. 2010 standards for delineating metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas. Federal Register. 2009;75(123).

Elixhauser A, Steinter C, Palmer L. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS). Chronic condition indicator for ICD-9-CM. 2007. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp#overview. Accessed September 30, 2018.

Buis ML. Direct and indirect effects in a logit model. Stata J. 2010;10(1):11–29.

Mahmoudi E, Jensen GA. Diverging racial and ethnic disparities in access to physician care: comparing 2000 and 2007. Med Care. 2012;50(4):327–34.

Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):799–805.

Qato DM, Daviglus ML, Wilder J, Lee T, Qato D, Lambert B. Pharmacy deserts are prevalent in chicago’s predominantly minority communities, raising medication access concerns. Health Aff. 2014;33(11):1958–65.

Pourat N, Roby DH, Wyn R, Marcus M. Characteristics of dentists providing dental care to publicly insured patients. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67(4):208–16.

Ma A, Sanchez A, Ma M. The impact of patient-provider race/ethnicity concordance on provider visits: updated evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(5):1011–20.

LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones KE. The Association of doctor-patient race concordance with health services utilization. J Public Health Policy. 2003;24:312–23.

Lightfoote JB, Fielding JR, Deville C, et al. Improving diversity, inclusion, and representation in radiology and radiation oncology part 1: why these matter. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11:673–80.

Saha S, Shipman SA. Race-neutral versus race-conscious workforce policy to improve access to care. Health Aff. 2008;27(1):234–45.

Logan HL, Guo Y, Dodd VJ, Seleski CE, Catalanotto F. Demographic and practice characteristics of Medicaid-participating dentists. J Pub Health Dentistry. 2013:1–8.

Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176–81.

Pourat N, Andersen RM, Marcus M. Assessing the contribution of the dental care delivery system to oral health care disparities. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75(1):1–9.

Yasaitis LC, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Association between physician supply, local practice norms, and outpatient visit rates. Med Care. 2013;51(6):524–31.

Neighbors HW, Musick MA, Williams DR. The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(6):759–77.

Jang SH. First-generation Korean immigrants’ barriers to healthcare and their coping strategies in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:93–100.

Jang SH. Here or there: recent U.S. immigrants’ medical and dental tourism and associated factors. Int J Health Serv. 2018;48(1):148–65.

Gardiner P, Whelan J, White LF, Filippelli AC, Bharmal N, Kaptchuk TJ. A systematic review of the prevalence of herb usage among racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(4):817–28.

Young JL, Griffith EE, Williams DR. The integral role of pastoral counseling by African-American clergy in community mental health. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(5):688–92.

Su D, Li L. Trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: 2002–2007. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):296–310.

Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, O'Connor BB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(4):535–45.

Felicilda-Reynaldo RFD, Choi SY, Driscoll SD, Albright CL. A national survey of complementary and alternative medicine use for treatment among Asian-Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-019-00936-z.

Cui Y, Hargreaves MK, Shu XO, et al. Prevalence and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine services use in low-income African Americans and whites: a report from the Southern Community Cohort Study. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(9):844–9.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD000214, PI: Gaskin).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study has been reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and determined to be Not Human Subjects Research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, K.S., Parikh, M.A., Thorpe, R.J. et al. Health Care Disparities in Race-Ethnic Minority Communities and Populations: Does the Availability of Health Care Providers Play a Role?. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 7, 539–549 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00682-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00682-w