Abstract

Introduction

Very few studies have been conducted on non-communicable diseases among resettled refugees. The purpose of the study was to examine longitudinal changes in obesity and overweight/obesity rates among resettled refugees and identify high-risk subgroups.

Methods

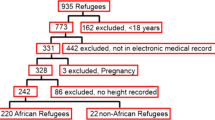

Longitudinal health assessment data of 818 children (2–18 years) and 1055 adults (≥19 years) were used from a refugee clinic in Buffalo, NY, during 2004–2014. Univariate and bivariate analyses were performed. Risk factors of obesity and overweight/obesity were assessed using multivariate regression models.

Results

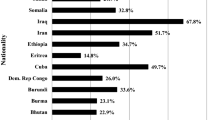

Obesity (8.7 to 12.7%) and overweight/obesity (16.9 to 26.7%) rates increased among children over 4.5 years (p < 0.01). Over 3.9 years, overweight/obesity rates increased in men (39.6 to 58.6%, p < 0.01) and women (55.1 to 73.5%, p < 0.01), exceeding the prevalence of overweight/obesity of 65.8% in US-born women. Interestingly, longitudinal overweight/obesity rates decreased among Middle Eastern (81.4 vs 78.0%, p < 0.01) and East European (75.0 vs 70.8%, p < 0.01) women. African children had 2.31-folds (odds ratio [OR] = 2.31; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.46–3.67) greater overweight/obesity risk than Asians. African girls who were not overweight or obese at baseline had the highest risk of becoming obese at follow-up visits (OR = 0.21; 95%CI = 0.09–0.52). For each additional year refugees lived in the USA, overweight/obesity risk among men (OR = 1.23; 95%CI = 1.09–1.39) and women (OR = 1.18; 95%CI = 1.04–1.35) increased.

Conclusion

Obesity and overweight/obesity rates increased among refugees, but significant variations existed. Overweight/obesity rate among refugee women surpassed the US average. African origin, baseline weight, and longer duration of stay in the USA were risk factors. Culturally tailored programs are needed to prevent obesity and reduce health disparities among refugees.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global trends. Forced displacement in 2015. http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2015.html. Accessed 6Aug 2016.

US Department of State. Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. Cumulative summary of refugee admissions. https://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/statistics/251288.htm. December 31, 2015. Accessed 4 Jan 2016. In.

Yun K, Hebrank K, Graber LK, Sullivan MC, Chen I, Gupta J. High prevalence of chronic non-communicable conditions among adult refugees: implications for practice and policy. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):1110–8.

Eckel RH. Obesity and heart disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee. American Heart Association Circulation. 1997;96(9):3248–50.

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–81.

Bhatta MP, Assad L, Shakya S. Socio-demographic and dietary factors associated with excess body weight and abdominal obesity among resettled Bhutanese refugee women in Northeast Ohio, United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(7):6639–52.

Amara AH, Aljunid SM. Noncommunicable diseases among urban refugees and asylum-seekers in developing countries: a neglected health care need. Glob Health. 2014;10:24.

Bhatta MP, Shakya S, Assad L, Zullo MD. Chronic disease burden among Bhutanese refugee women aged 18-65 years resettled in Northeast Ohio, United States, 2008-2011. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(4):1169–76.

Heney JH, Dimock CC, Friedman JF, Lewis C. Pediatric refugees in Rhode Island: increases in BMI percentile, overweight, and obesity following resettlement. R I Med J. 2013;98(1):43–7.

Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM. Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants to the US: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2023–34.

Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev. 2001;2(3):159–71.

Dookeran NM, Battaglia T, Cochran J, Geltman PL. Chronic disease and its risk factors among refugees and asylees in Massachusetts, 2001-2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A51.

Rondinelli AJ, Morris MD, Rodwell TC, Moser KS, Paida P, Popper ST, et al. Under- and over-nutrition among refugees in San Diego County, California. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(1):161–8.

Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–92.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–14.

Grijalva-Eternod CS, Wells JC, Cortina-Borja M, Salse-Ubach N, Tondeur MC, Dolan C, et al. The double burden of obesity and malnutrition in a protracted emergency setting: a cross-sectional study of Western Sahara refugees. PLoS Med. 2012;9(10):e1001320.

Bilukha OO, Jayasekaran D, Burton A, Faender G, King'ori J, Amiri M, et al. Nutritional status of women and child refugees from Syria-Jordan, April-May 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(29):638–9.

Roshania R, Narayan KM, Oza-Frank R. Age at arrival and risk of obesity among US immigrants. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(12):2669–75.

Kruseman M, Barandereka NA, Hudelson P, Stalder H. Post-migration dietary changes among african refugees in Geneva: a rapid assessment study to inform nutritional interventions. Soz Praventivmed. 2005;50(3):161–5.

Kinzie JD, Riley C, McFarland B, Hayes M, Boehnlein J, Leung P, et al. High prevalence rates of diabetes and hypertension among refugee psychiatric patients. In: J Nerv Ment Dis. United States; 2008. p. 108–12.

Patil CL, Hadley C, Nahayo PD. Unpacking dietary acculturation among new Americans: results from formative research with African refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(5):342–58.

Hazuda HP, Mitchell BD, Haffner SM, Stern MP. Obesity in Mexican American subgroups: findings from the San Antonio Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(6 Suppl):1529s–34s.

Akil L, Ahmad HA. Effects of socioeconomic factors on obesity rates in four southern states and Colorado. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(1):58–62.

Ravelli AC, van Der Meulen JH, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Bleker OP. Obesity at the age of 50 y in men and women exposed to famine prenatally. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(5):811–6.

Peterman JN, Wilde PE, Liang S, Bermudez OI, Silka L, Rogers BL. Relationship between past food deprivation and current dietary practices and weight status among Cambodian refugee women in Lowell, MA. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1930–7.

Goel MS, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Wee CC. Obesity among US immigrant subgroups by duration of residence. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2860–7.

Hazuda HP, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Eifler CW. Effects of acculturation and socioeconomic status on obesity and diabetes in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(6):1289–301.

Reed D, McGee D, Cohen J, Yano K, Syme SL, Feinleib M. Acculturation and coronary heart disease among Japanese men in Hawaii. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115(6):894–905.

Alnohair. Obesity in gulf countries. In: Int J Health Sci (Qassim); 2014. p. 79–83.

Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M, Guricci S. Asians are different from Caucasians and from each other in their body mass index/body fat per cent relationship. Obes Rev. 2002;3(3):141–6.

Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Roche AF. Human body composition and the epidemiology of chronic disease. Obes Res. 1995;3(1):73–95.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mrs. Jessie Mossop, Information Services and Reporting Manager at Jericho Road Community Health Center, for her assistance in data retrieval. The content of the paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. This study was partly supported by research grants from the National Institute of Health (NIH, U54 HD070725, 1R01HD064685-01A1). The U54 project (U54 HD070725) is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD). Dr. Youfa Wang is the principal investigator of the grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was partly supported by research grants to Dr. Youfa Wang from the National Institute of Health (NIH, U54 HD070725, 1R01HD064685-01A1). The U54 project (U54 HD070725) is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was received from the State University of New York at Buffalo for the study. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mulugeta, W., Glick, M., Min, J. et al. Longitudinal Changes and High-Risk Subgroups for Obesity and Overweight/Obesity Among Refugees in Buffalo, NY, 2004–2014. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 187–194 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0356-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0356-y