Abstract

Background

The recommended home health financial penalty program for preventable readmission does not factor race/ethnicity and neighborhood racial compositions into the determination of preventable readmission rates. Home health agencies may avoid beneficiaries from certain racial/ethnic groups and neighborhoods if these two factors have an effect on preventable readmissions. We examined the association between preventable readmissions with race/ethnicity and neighborhood racial composition.

Methods

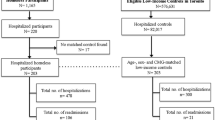

Several 2009 national data were used, such as the Master Beneficiary Summary File, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File, and Outcome Assessment Information Set. Our sample consisted of diabetic Medicare home health beneficiaries (African-Americans and Whites only). We analyzed predictors of time-to-first 30-day preventable readmission, including short/long-term diabetic complications, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma, bacterial pneumonia, dehydration, urinary tract infection, hypertension, heart failure, angina without procedure, uncontrolled diabetes, and lower-extremity amputation.

Results

There were 86,567, 17,262, and 11,392 observations in neighborhoods with low (6 % African-Americans), moderate (35 % African-Americans), and high (76 % African-Americans) density of African-Americans, respectively. Using Cox regression models, we found that in neighborhoods with moderate and high density of African-Americans, African-Americans had 21 % (hazard ratio (HR) 1.21; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.04–1.39) and 24 % (HR 1.24; 95 % CI 1.01–1.52) significantly higher hazards of 30-day preventable readmissions than Whites, respectively.

Conclusion

Race and neighborhood racial compositions are beyond home health providers’ control. These two factors should be considered as covariates for the preventable readmissions in the recommended home health financial penalty program.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Home health care services. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2014. p. 213–40. Chapter 9.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmission Reduction Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

Avalere Health LLC. The Medicare Home Health Benefit/ Program Costs and Beneficiary Characteristics. 2009. http://www.almostfamily.com/pdf/20090715_AHHQI%20Chart%20Book.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2015

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16.

Cooper HL, Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Friedman R. Residential segregation and injection drug use prevalence among Black adults in US metropolitan areas. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):344–52.

Harris MI, Eastman RC, Cowie CC, Flegal KM, Eberhardt MS. Racial and ethnic differences in glycemic control of adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):403–8.

Krivo LJ, Peterson RD, Kuhl DC. Segregation, racial structure, and neighborhood violent crime. AJS. 2009;114(6):1765–802.

Kwate NO. Fried chicken and fresh apples: racial segregation as a fundamental cause of fast food density in black neighborhoods. Health Place. 2008;14(1):32–44.

Peng TR, Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH. Social support, home health service use, and outcomes among four racial-ethnic groups. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):503–13.

Brega AG, Goodrich GK, Powell MC, Grigsby J. Racial and ethnic disparities in the outcomes of elderly home care recipients. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2005;24(3):1–21.

Yeboah-Korang A, Kleppinger A, Fortinsky RH. Racial and ethnic group variations in service use in a national sample of Medicare home health care patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(6):1123–9.

Herrin J, St Andre J, Kenward K, Joshi MS, Audet AM, Hines SC. Community factors and hospital readmission rates. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):20–39.

Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Moss A, Harris-Kojetin L, Valverde R. Home health care and discharged hospice care patients: United States, 2000 and 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011;27(38):1–27.

Madigan EA, Gordon NH, Fortinsky RH, Koroukian SM, Piña I, Riggs JS. Rehospitalization in a national population of home health care patients with heart failure. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2316–38.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Cabin W, Himmelstein DU, Siman ML, Woolhandler S. For-profit Medicare home health agencies’ costs appear higher and quality appears lower compared to nonprofit agencies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;3(8):1460–5.

Bennett KJ, Probst JC. Thirty-day readmission rates among dual-eligible beneficiaries. J Rural Health. 2015. doi:10.1111/jrh.12140.

Bynum JP, Rabins PV, Weller W, Niefeld M, Anderson GF, Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, Medicare expenditures, and hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):187–94.

Bennett KJ, Probst JC, Vyavaharkar M, Glover SH. Lower rehospitalization rates among rural Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes. J Rural Health. 2012;28(3):227–34.

Toth M, Holmes M, Van Houtven C, Toles M, Weinberger M, Silberman P. Rural Medicare beneficiaries have fewer follow-up visits and greater emergency department use postdischarge. Med Care. 2015;53(9):800–8.

LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res and Rev. 2000;57 Suppl 1:146–61.

Hasnain-Wynia R, Kang R, Landrum MB, Vogeli C, Baker DW, Weissman JS. Racial and ethnic disparities within and between hospitals for inpatient quality of care: an examination of patient- level Hospital Quality Alliance measures. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2):629–48.

Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575–84.

Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-level racial disparities in acute myocardial infarction treatment and outcomes. Med Care. 2005;43(4):308–19.

Groeneveld PW, Laufer SB, Garber AM. Technology diffusion, hospital variation, and racial disparities among elderly Medicare beneficiaries: 1989–2000. Med Care. 2005;43(4):320–9.

Sarrazin MS, Campbell ME, Richardson KK, Rosenthal GE. Racial segregation and disparities in health care delivery: conceptual model and empirical assessment. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(4):1424–44.

Shea JA, Beers BB, McDonald VJ, Quistberg DA, Ravenell KL, Asch DA. Assessing health literacy in African American and Caucasian adults: disparities in rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine (REALM) scores. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):575–81.

Gaskin DJ, Dinwinddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary RR. Residential segregation and the availability of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2004;47(6):2353–76.

Greene J, Blustein J, Weitzman BC. Race, Segregation, and Physicians’ Participation in Medicaid. Milbank Q. 2006;84(2):239–72.

Wolff JL, Meadow A, Weiss CO, Boyd CM, Leff B. Medicare home health patients’ transitions through acute and post-acute care settings. Med Care. 2008;46(11):1188–93.

Jiang HJ, Andrews R, Stryer D, Friedman B. Racial/ethnic disparities in potentially preventable readmissions: the case of diabetes. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95(9):1561–7.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Prevention Quality Indicators http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/PQI_TechSpec.aspx. Accessed November 10, 2015.

Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, Komaromy M, Vranizan K, Lurie N. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–11.

Billings J, Zeitel L, Lukomnik J, Carey TS, Blank AE, Newman L. Impact of socioeconomic status on hospital use in New York City. Health Aff (Millwood). 1993;12(1):162–73.

Torio CM, Andrew RM. Geographic variation in potentially preventable hospitalizations for acute and chronic conditions, 2005–2011. Statistical Brief #178.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Brief, Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (US). 2006 Feb-2014 Sep.

Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Probst JC. Health care access in rural areas: evidence that hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in the United States may increase with the level of rurality. Health Place. 2009;15(3):731–40.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Comorbidity Software Version 3.7. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp. Accessed January 5, 2016

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

Riggs JS, Madigan EA, Fortinsky RH. Home Health Care Nursing Visit Intensity and Heart Failure Patient Outcomes. Home Health Care Manag and Pract. 2011;23(6):412–20.

Bower KM, Thorpe Jr RJ, Rohde C, Gaskin DJ. The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States. Prev Med. 2014;58:33–9.

Wu JR, Lennie TA, De Jong MJ, Frazier SK, Heo S, Chung ML, et al. Medication adherence is a mediator of the relationship between ethnicity and event-free survival in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2010;16(2):142–9.

Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Hammill BG, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716–22.

Kociol RD, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Hammill BG, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, et al. Associations of patient demographic characteristics and regional physician density with early physician follow-up among medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with heart failure. Am J Cardio. 2011;108(7):985–91.

Gaskin DJ, Thorpe Jr RJ, McGinty EE, Bower K, Rohde C, Young JH, et al. Disparities in diabetes: the nexus of race, poverty, and place. Am J Public Health. 2013;104(11):2147–55.

Kershaw KN, Diez Roux AV, Burgard SA, Lisabeth LD, Mujahid MS, Schulz AJ. Metropolitan-level racial residential segregation and black-white disparities in hypertension. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(5):537–45.

LaVeist T, Pollack K, Thorpe Jr R, Fesahazion R, Gaskin D. Place, not race: disparities dissipate in southwest Baltimore when blacks and whites live under similar conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1880–7.

Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmissions—truth and consequences. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1366–9.

Joynt KE, Jha AK. Characteristics of hospitals receiving penalties under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA. 2013;309(4):342–3.

Konetzka RT, Werner RM. Disparities in long-term care: building equity into market-based reforms. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):491–521.

Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, Birkmeyer JD. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1046–53.

Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn JS, Mor V. Separate and unequal: racial segregation and disparities in quality across U.S. nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(5):1448–58.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript was accepted when the corresponding author was affiliated with UNTHSC but was published after the corresponding author joined UAMS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the IRB at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standard.

Funding

This study was supported by the Junior Faculty Seed Fund at the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC). The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNTHSC.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

This study was based on the secondary data from the Medicare claim and assessment files and several national data at the organization and community levels. The authors were not able to use these secondary data to identify individual personal information. Thus obtaining the consent from individual person was not feasible; however, the authors followed the rules under the CMS data user agreement.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, HF., Homan, S., Carlson, E. et al. The Impact of Race and Neighborhood Racial Composition on Preventable Readmissions for Diabetic Medicare Home Health Beneficiaries. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4, 648–658 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0268-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0268-2