Abstract

Introduction

Nationally, about one third of women with breast cancer (BC) are diagnosed at late stage, which might be reduced with greater utilization of BC screening. The purpose of this paper is to examine the predictors of BC mammography use among women with Medicaid, and differences among Medicaid beneficiaries in their propensity to use mammography.

Methods

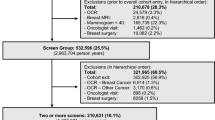

The sample included 2,450,527 women drawn from both fee-for-service and managed care Medicaid claims from 25 states, during 2006–2008. The authors used multilevel modeling of predictors at person, county, and state levels of influence and examined traditional factors affecting access and the expanded scope of practice allowed for the nurse practitioner (NP) in some states to provide primary care independent of physician oversight.

Results

Black [OR = 0.87; 95 % CI (0.87–0.88)] and American Indian women [OR = 0.74; 95 % CI (0.71–0.76)] had lower odds ratio of mammography use than white women, while Hispanic [OR = 1.06; 95 % CI (1.05–1.07)] had higher odds ratio of mammography use than white women. Living in counties with higher Hispanic residential segregation [OR = 1.16; 95 % CI (1.10–1.23)] was associated with a higher odds ratio of mammography use compared to areas with low Hispanic residential segregation, whereas living among more segregated black [OR = 0.78; 95 % CI (0.75–0.81)] or Asian [OR = 0.19; 95 % CI (0.17–0.21)] communities had lower odds ratio compared to areas with low segregation. Holding constant statistically the perceived shortage of MDs, which was associated with significantly lower mammography use, the NP regulatory variable [OR = 1.03; 95 % CI (1.01–1.07)] enhanced the odds ratio of mammography use among women in the six states with expanded scope of practice, compared with women residing in 19 more restrictive states.

Conclusions

Racial and ethnic disparities exist in the use of mammography among Medicaid-insured women. More expansive NP practice privileges in states are associated with higher utilization, and may help reduce rural disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Shickle LM, Farrell N. Differences in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment: experiences of insured and uninsured women in a safety-net setting. Inquiry. 2008;45(3):323–39.

Kuo TM, Mobley LR, Anselin L. Geographic disparities in late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in California. Health Place. 2011;17(1):327–34.

Radley DC, Schoen C. Geographic variation in access to care—the relationship with quality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):3–6.

Peipins LA, Graham S, Young R, Lewis B, Flanagan B. Racial disparities in travel time to radiotherapy facilities in the Atlanta metropolitan area. Soc Sci Med. 2013;89:32–8.

Niccolai LM, Julian PJ, Bilinski A, Mehta NR, Meek JI, Zelterman D, et al. Geographic poverty and racial/ethnic disparities in cervical cancer precursor rates in Connecticut, 2008–2009. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):156–63.

Wagner SE, Hurley DM, Hebert JR, McNamara C, Bayakly AR, Vena JE. Cancer mortality-to-incidence ratios in Georgia: describing racial cancer disparities and potential geographic determinants. Cancer. 2012;118(16):4032–45.

Lian M, Schootman M, Doubeni CA, Park Y, Major JM, Stone RA, et al. Geographic variation in colorectal cancer survival and the role of small-area socioeconomic deprivation: a multilevel survival analysis of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(7):828–38.

Freeman HP, Chu KC. Determinants of cancer disparities: barriers to cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2005;14(4):655–69 .v

Coughlin SS, Richardson LC, Orelien J, Thompson T, Richards TB, Sabatino SA, et al. Contextual analysis of breast cancer stage at diagnosis among women in the United States, 2004. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2009;2:45–6.

Bhanegaonkar A, Madhavan SS, Khanna R, Remick SC. Declining mammography screening in a state Medicaid fee-for-service program: 1999–2008. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(8):821–9.

Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Breen N, Tangka F, Shaw KM. Disparities in mammography use among US women aged 40–64 years, by race, ethnicity, income, and health insurance status, 1993 and 2005. Med Care. 2008;46(7):692–700.

Hunt BR, Whitman S, Hurlbert MS. Increasing black:white disparities in breast cancer mortality in the 50 largest cities in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38(2):118–23.

National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). Scope of Practice Legislative Database, 2011–2013. 2013. http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/health/scope-of-practice-legislation-tracking-database.aspx. Accessed Feb 2015.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Research Data Assistance Center. Medicaid data 2006–2008. 2013. Minneapolis, MN: Research Data Assistance Center. Available from: http://www.resdac.org/cms-data/search?f[0]=im_field_program_type%3A2

Byrd V, Dodd AH. Assessing the usability of encounter data for enrollees in comprehensive managed care across MAX 2007–2009, Medicaid Policy Brief, Brief 15. 2012 Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

U.S. Preventive Task Force. Screening for breast cancer. 2002. cited 2014 August 25. Available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsbrca2002.htm

Research Triangle Institute (RTI). Spatial impact factor database. 2014. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International. Available from: https://rtispatialdata.rti.org

Massey DS, Denton NA. The dimensions of residential segregation. Sociol Forum. 1988;67:281–315.

Jaen CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(2):166–71.

Stange K. How does provider supply and regulation influence health care markets? Evidence from nurse practitioners and physician assistants. J Health Econ. 2014;33:1–27.

Cassidy A. Health policy brief: nurse practitioners and primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012.

Yee T, Boukus E, Cross D, Samuel D. Primary care workforce shortages: nurse practitioner scope-of-practices laws and payment policies. National Institute for Health Care Reform, Research Brief No. 13. 2013. 2013 [cited 2014 June]. Available from: http://www.nihcr.org/PCP-Workforce-NPs

Kuo YF, Loresto Jr FL, Rounds LR, Goodwin JS. States with the least restrictive regulations experienced the largest increase in patients seen by nurse practitioners. Health Aff. 2013;32(7):1236–43.

Hansen-Turton T. Nurse practitioners as leaders in primary care: current challenges and future opportunities. National Conference of State Legislatures: Louisville, KY; 2010 .Available from: http://www.ncsl.org/documents/health/hansenturtonpp.pdf

Ewing J, Hinkley K. Meeting the primary care needs of rural America: examining the role of non-physician providers. The Rural Health Connection. 2013.

American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). State profiles: reforming the health care system, 12th edition. 2003. [cited 2015 February 17]. Available from: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/health/d17984_reform_2003.pdf

Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16.

Dai D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010;16(5):1038–52.

Schulz AJ, Williams DR, Israel BA, Lempert LB. Racial and spatial relations as fundamental determinants of health in Detroit. Milt Q. 2002;80(4):677–707 .iv

Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox lost: explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography. 2004;41(3):385–415.

Kramer MR, Hogue CR. Is segregation bad for your health? Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:178–94.

Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, Brawarsky P, Neville BA, Williams DR. Racial segregation and disparities in cancer stage for seniors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):699–705.

Mobley LR, Kuo TM, Andrews L. How sensitive are multilevel regression findings to defined area of context?: a case study of mammography use in California. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(3):315–37.

Mobley LR, Kuo TM, Driscoll D, Clayton L, Anselin L. Heterogeneity in mammography use across the nation: separating evidence of disparities from the disproportionate effects of geography. Int J Health Geogr. 2008;7:32.

Mobley LR, Kuo TM, Clayton LJ, Evans WD. Mammography facilities are accessible, so why is utilization so low? Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(6):1017–28.

Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ, Almgren GR, Mayer JD, Huebner CE. Birth outcomes among urban African-American women: a multilevel analysis of the role of racial residential segregation. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3030–45.

LaVeist TA. The political empowerment and health-status of African-Americans—mapping a new territory. AJS. 1992;97(4):1080–95.

Mobley L, Kuo T. United States health policies and late-stage breast and colorectal cancer diagnosis: why such disparities by age? Heal Econ Rev. 2015;5:20. doi:10.1186/s13561-015-0058-2.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding support for Lee Mobley, Sujha Subramanian, Sonja Hoover, and Jiantong Wang was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Contract No. 200-2008-27958, Task order 35, to RTI International).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. The research does not involve human participants or animals and did not require informed consent. This manuscript has not been submitted to more than one journal for simultaneous consideration. This manuscript has not been published previously (partly or in full). This study has not been split up into several parts to increase the quantity of submissions and submitted to various journals or to one journal over time. No data have been fabricated or manipulated (including images) to support our conclusions. No data, text, or theories by others are presented as if they were the author’s own. Proper acknowledgements to other works have been given. Consent to submit has been received explicitly from all co-authors, as well as from the responsible authorities—tacitly or explicitly—at the institute/organization where the work has been carried out. Authors whose names appear on this manuscript have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work and therefore share collective responsibility and accountability for the results.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mobley, L.R., Subramanian, S., Tangka, F.K. et al. Breast Cancer Screening Among Women with Medicaid, 2006–2008: a Multilevel Analysis. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4, 446–454 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0245-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0245-9