Abstract

Conducted physically, supervised group-based falls prevention exercise programs have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the risk of falls among older adults. In this study, we aimed to assess the acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of a virtual supervised group-based falls prevention exercise program (WE-SURF™) for community-dwelling older adults at risk of falls.

Method

A preliminary study utilizing virtual discussions was conducted to assess the acceptability of the program among six older adults. Effectiveness was evaluated in a randomized controlled feasibility study design, comprising 52 participants (mean age: 66.54; SD: 5.16), divided into experimental (n = 26) and control (n = 26) groups. The experimental group engaged in a 6-month WE-SURF™ program, while the control group received standard care along with a fall’s prevention education session. Feasibility of the intervention was measured using attendance records, engagement rates from recorded videos, dropouts, attrition reasons, and adverse events.

Results

Preliminary findings suggested that WE-SURF™ was acceptable, with further refinements. The study revealed significant intervention effects on timed up and go (TUG) (η2p:0.08; p < 0.05), single leg stance (SLS) (η2p:0.10; p < 0.05), and lower limb muscle strength (η2p:0.09; p < 0.05) tests. No adverse events occurred during the program sessions, and both attendance and engagement rates were high (> 80% and 8/10, respectively) with minimal dropouts (4%). The WE-SURF™ program demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the risk of falls while enhancing muscle strength and balance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, WE-SURF™ was demonstrated to be an acceptable, feasible, and effective virtual supervised group-based exercise program for fall prevention in community-dwelling older adults at risk of falls. With positive outcomes and favourable participant engagement, WE-SURF™ holds the potential for wider implementation. Further research and scaling-up efforts are recommended to explore its broader applicability.

(Registration number: ACTRN 12621001620819).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, the prevalence of falls among older adults is expected to rise due to factors such as a rapidly aging population, polypharmacy, multimorbidity (including frailty), and cognitive impairment [2]. At least one third of older adults aged 65 years and above worldwide have been reported to experience at least one fall each year [3]. Similarly, fall prevalence in Malaysian older adults’ ranges from 4.2% to 47% depending on settings [4,5,6,7,8,9] with an incidence rate of occasional and recurrent falls of 8.47 and 3.21 per 100 person-years respectively [10].

The consequences of falls are debilitating and leads to increased personal, societal and economic burden. An estimated 17 million years of life lost (YLLs), 20 million years lived with disability (YLDs) and 36 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) was reported in the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study due to falls and associated adverse outcomes [11]. There is a need to implement falls risk reduction initiatives on a broader scale for older adults, as indicated in the World Falls Guidelines [12].

Although, falls are considered multifactorial in nature, muscle weakness and poor balance are among the main risk factors for increased falls among older adults [7, 13,14,15]. In addition, compared to their counterparts in Western countries, the physical activity level of community-dwelling older people in Southeast Asia is generally considered inadequate [16]. The prevalence of low physical activity among Malaysian older adults has been reported as 21% [17]. In contrast, the overall prevalence of physical inactivity in older adults across 16 European countries was found to be 12.5% [18].

A structured and planned exercise program may be able to counteract fall risk factors such as muscle weakness and impaired balance. A meta-analysis with 44 studies found that regular exercise that challenges balance is the most effective method to prevent falls or fall injuries [19]. A subsequent Cochrane review found that multicomponent exercise is effective in reducing rate of falls by 34% (95% CI 12% to 15%) [20].

The World Falls Guidelines recommends exercise that challenges balance and includes strengthening and functional components undertaken at least three times a week, progressed in intensity for at least 12 weeks and continued longer for greater effects to prevent falls in community dwelling older adults [2]. Other effective falls prevention programs range from simple falls prevention education [21, 22] to more challenging exercises such as square stepping exercises [23, 24] and backward chaining exercises [25]. Furthermore, it is crucial to design exercises that are suitable for the targeted group to ensure both adherence to and the effectiveness of exercise programs [1, 26,27,28,29].

Despite physical exercise and activity having sufficient evidence for prevention and management of falls and falls related issues in older adults, the uptake of both remains low, more so in Malaysia [12, 30]. There are also limited opportunities for older adults to engage in evidence based and supervised exercise programs, particularly for those with low to intermediate falls risk. Moreover, older adults with falls who have been managed in healthcare facilities may not be adequately self-efficient for compliance in self- management, especially with regards to maintaining regular participation in physical exercise programs [31, 32].

Recent reports indicate that virtual group-based exercise programs are convenient and feasible for Malaysian older adults [33]. Additionally, it’s noteworthy that more than 80% of healthy Malaysian older adults are likely to use digital technology [34]. Furthermore, online falls prevention interventions, are shown to have a significant improvement in fall risk, balance, and fall efficacy [35]. To address the issues of poor uptake and adherence of evidence-based fall prevention exercise among Malaysian older adults we tested the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of a virtual fall prevention exercise group.

Methodology

Study design

This was a randomized controlled feasibility trial conducted between March 2021 and October 2021. Human research ethics approval was obtained through the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the University (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (JEP-2020-611) and the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Malaysia (NMRR-20–2289-56760). The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (Registration number: ACTRN 12621001620819).

A preliminary study was carried out to assess the acceptability of the program among six participants (mean age: 66.2 years, 61–76 years) and to determine optimal delivery strategies. Virtual discussions were conducted with the participants using semi-structured questions after two trial sessions of the level 1 virtual exercise program. The moderator (one of the researchers) conducted the discussions, assisted by one co-moderator (a physiotherapist), who was not involved in the intervention design or delivery.

The sample size calculation for the trial was based on the G*power 3.1 statistical power analysis program [36]. The power analysis indicated that a total sample of 42 participants was required to detect a significant difference between two groups, with an effect size of 0.40 (35), using the time up and go test (TUG) as the primary outcome indicative of the risk of fall. While α represents the significance level (p < 0.05), and 1-β err prob denotes the power, set at 0.80. A 20% dropout rate was estimated and thus a total sample size of 52 participants (26 participants per group) was considered adequate for this study.

Participants

Participants were recruited via poster and word of mouth, advertised at government clinics, hospitals, community groups such as local churches, mayoral offices, senior activity centres (PAWE), and volunteers from local non-governmental organizations (Sarawak Gerontology and Geriatrics Association, Women’s Institute Kuching). Fifty-two adults aged 60 years and older with risk of falls, measured using the timed up and go (TUG) test with a cut-off value of 11.2 s and below, living in the urban city area around Kuching, Sarawak participated in this study. Kuching, Sarawak is located in the north western region of the island of Borneo in Malaysia. Exclusion criteria included those who were unable to complete an hour’s exercise program, have acute or chronic conditions, including severe musculoskeletal pain, recent history of fracture within the last 6 months, cardiovascular diseases like stroke with hemiplegia, unstable angina. neurological diseases with progressive weakness, postural hypotension and, vestibular problems. Those with uncorrected visual issues, cognitive deficits (assessed using Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test with score less than 20) [37] and those participating in other exercise programs in the previous 6 weeks or illiterate were also excluded.

The intervention

Development of WE-SURF ™ was adapted from available evidence on falls prevention programs [22, 23, 25, 38,39,40] to suit the local older population. WE- SURF™ stands for “Warga Emas—Steady, UpRight and Firm exercise. “Warga Emas” is the Malaysian language term for older adults. “Steady, UpRight and Firm” represents our objectives to optimize fall risk, balance and muscle strength.

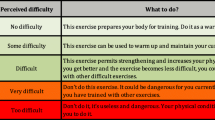

WE-SURF™ is a 24-week virtual supervised group-based exercise program of three levels progressive exercise. It included one session of falls prevention program education that covered topics such as an overview of falls, consequences of falls in older adults, fall risk factors, fall prevention strategies, and how to get up after a fall. The preparation of an online class included discussion and question–answer sessions on the set up of the tools for virtual exercises and a trial session demonstration. There was a total of 48 online exercise sessions. Exercises included warm up, resistance exercise using strap on weights, balance training, square-stepping, cool down and backwards chaining to train for getting up from floor. WE-SURF TM was delivered online via Zoom™ and supervised by a physiotherapist with 10 years’ experience. Each WE-SURF™ duration ranged from 75–90 min with group-sessions including a maximum of seven older persons. The virtual session was conducted twice per week for 6 months. In the first online education session, participants were requested to test their smart mobiles, tablets or computers and any technical issues were solved with the help of the therapist who was online and family members at home. This included placement of the smart device for better viewability, home space utilization and safety. The overview of WE-SURF™ program is as depicted in the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) (Table 1).

Control group

Participants in the control group attended one session of virtual fall prevention education session and continued their usual care or activities routine without any restrictions or changes until the end of the study.

Baseline measures

Sociodemographic information

Sociodemographic information was obtained from all participants through a standardized data collection document. Details obtained included gender, race, ethnicity, education level, marital status, living arrangements, employment status, medical history, alcohol intake, smoking status, history of falls within the past 12 months and comorbidities. Modified Baecke physical activity score, cognitive deficits based on MoCA test scale and Geriatric Depression score (GDS) were also obtained.

The modified Baecke physical activity score was used to assess the level of physical activity. It comprises 19-items within categories of household activities, sports activities and leisure time activities rated using a five-point Likert scale. The test–retest validity was reported to be good for culturally diverse populations [41] and older adults [42].

A short-form GDS was used to indicate depression level for the participants. Scores of less than 4 were considered normal; 5–8 considered mild depression; 9–11 indicated moderate depression; and more than 12 indicated severe depression. While validated GDS-15 consisted of two domains; depression and psychosocial activities, only the overall score was considered [43]. The reliability was considered good with reported overall value for Cronbach’s alpha: 0.890.

Acceptability of the exercise intervention

Acceptability was ascertained in the preliminary study with virtual discussion to explore participants experience and perceptions towards the WE-SURF™ exercise program. Semi structured questions were used to conduct one discussion interview via Zoom ™. Participants were also asked to rate the level of acceptability after two sessions of trials virtual exercise program on 1–10 Likert scale with 10 being completely acceptable.

Feasibility of the exercise intervention

The feasibility of the intervention measured using attendance records, engagement rate from the recorded videos, dropouts, attrition reasons, and adverse events. Attendance of each participant in every session was recorded; dropouts and attrition reasons or reason of absence for each session were also recorded. The engagement rate was determined based on three randomly chosen recorded videos for each level and assessed by another blinded assessor (a physiotherapist not involved in the study). Each participant was rated from 0 to 10 (none to full engagement) based on their engagement throughout the session for each level. Participants were requested to report any adverse events, such as musculoskeletal pain, falls, or hospitalization, to the instructor during the program and the 6-month assessment.

Primary outcome measurements

Time up and go test (TUG)

The TUG test has a high test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.92–0.0.99) in older adults [44]. From a sitting position on an armrest chair, each participant was requested to stand, walk three metres at a comfortable pace, turn, and walk back to the chair and sit down. The time taken was recorded in seconds, from the time the participant began to stand until the participant sat back down. Participants performed this test three times; average scores recorded in seconds were used in the analysis.

Single leg stand test (SLS)

The SLS test is a reliable clinical test which assessed the static balance [45]. The time from when participant lifted one leg and stands on one foot without arm support until the lifted leg touched the ground was recorded in seconds. Each participant was required to perform this test three times with the longest performance recorded as the final score.

Dominant handgrip strength (HGS)

The dominant HGS is a valid and reliable measurement tool to determine upper limb muscle strength. The test–retest reliability for the dominant HGS test was (ICC = 0.97, p = 0.01) [46] Participants were asked to use a standard dynamometer (Patterson Medical, UK) to apply their maximum grip strength in a sitting position with the arm adducted, the forearm unsupported, the elbow flexed at 90 degrees, and the wrist in a neutral position. Three tests were performed with the highest value recorded as the participant’s grip strength.

Five times sit to stand test (5TSTS)

The 5TSTS test is a clinical test used to measure lower extremity strength. It has high test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.81) [47]. Participant stood up from the chair and sat back down for a total of five repetitions. Time recording started from the moment standing was initiated and ended after five repetitions of the STS tasks were completed.

Secondary outcome measurements

Quality of life (EQ-5D)

The EQ-5D has been widely translated and its validity within the Malaysian population has been established [48]. We used both the Malay and English versions of the EQ-5D. The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was used in this questionnaire for participant report of perceived health status which ranged from 0 (worst health status) to 100 (best possible health status). The EQ-5D questionnaire has an acceptable test–retest reliability value ICC = 0.79 [49].

Short fall efficacy scale-international (FES-I)

The short FES-I consists of seven items [50] which measures the level of fear of falling (FoF) during the physical and social activities of daily life. The FES-I has a high test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.93) and correlates with both the level of anxiety and getting up from a fall. Evidence shows it is reliable and valid for older adults [51]. The short FES-I is considered preferable in the Malaysian cultural population compared to the original 16-item version of the FES-I considering the longer version comprises items activities of daily living not routinely performed by the Malaysian older adults [52]. A fall diary was given to the participants or their carers to record any fall episodes.

Randomisation and blinding

The assessor who assessed the pre-post measures, a physiotherapist, was blinded to the groups. Since the recruitment process involved one-to-one screening, block randomisation was carried out based on the recruitment batches [53]. Each batch consisted of 12 to 14 participants. Average time from baseline assessment to randomisation was within 1 week. Participants were randomised into the experimental or control groups via block randomisation. The randomisation of the participants was conducted by a research assistant, who was not involved in the design, delivery, or assessment of the intervention or intervention outcomes. The randomisation used a computer-generated random number table from the free online randomisation website www.randomizer.org. Four blocks of randomisation were carried out individually based on availability of the participants.

Data analysis

For the preliminary study, qualitative data was analysed thematically. The discussion was audio-recorded, transcribed, and coded using the thematic analysis method for qualitative data analysis. The complete transcripts were sent to participants to ensure trustworthiness and data familiarity to ensure rigorous data analysis [54].

All statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 24.0. An alpha level of (0.05) was considered for all the statistical tests. For the descriptive analysis, statistics on clinical parameters and participants’ characteristics were reported by presenting frequencies via percentages or means with standard deviations. The experimental and control groups were compared using the chi-square test for dichotomous variables, while the t-test was employed for continuous variables. The results of the randomized trial were analysed using repeated measures analysis of variance to assess within, between, and interaction effects for the primary outcome, which included the risk of fall (TUG test), balance, muscle strength assessment, and secondary outcome measurements.

In the main analyses, participants were included in the groups as they were randomized and the intention-to-treat principle was used. In the analyses of rates and dropouts, censored observations were considered with reasons for dropout reported. Additional analyses were conducted where missing data were imputed using baseline assessment data.

Results

Acceptability

One researcher at a public hospital conducted screening and identified 6 out of 20 older adults as eligible participants. A total of 6 participants were enrolled in the preliminary study, with a mean age (SD): 66.17 ± 4.67 years. Three themes providing participant views emerged from the discussion (Table 2).

The first theme was participants’ overall experience of the virtual exercise program using any device (mobile, tables, computer). Participants had limited previous experience of virtual program of any nature, with only two having previously participated in online classes (for religious purposes and music lessons). Participants with no prior experience in virtual exercise program agreed to trying an online exercise program to enable themselves to exercise at home safely during the COVID-19 pandemic. The second theme that emerged concerned participants’ perceptions of the virtual group exercise program design. Information on exercise intensity, tailoring to specific condition and design, as well as the delivery method, provided useful information for refining the program for the next phase. Most participants agreed that two sessions a week of virtual exercise were sufficient to suit their daily routines and that over an hour per session was ideal for them.

Lastly all participants mentioned that they were satisfied with the exercise design, as they perceived it to be a comprehensive program that involved multicomponent exercise. Most participants valued a virtual exercise program which used pre-recorded videos, compared to live demonstrations. Pre-recorded videos would involve recording exercise routines or demonstrations ahead of time, allowing participants to follow the content during the exercise session, while the researcher, acting as a physiotherapist, can monitor or guide participants. It was clearer and easier for participants to follow, while the instructor could monitor each participant’s movements and correct them when required.

The acceptability rates generally ranged from seven to nine with a median of nine. These participants were interested in joining the subsequent phase of the exercise program. The trial sessions recorded a 100% class attendance from the first to the second session with mean of 100%. The instructor observed high levels of engagement from participants in the class (with a mean score of 8/10), and participants were generally successful in understanding and replicating the instructions provided. They were able to perform the movements and exercises as demonstrated in the pre-recorded video, although there were occasional instances of incorrectly performing some of the movements.

Effectiveness on outcome measures

After the preliminary study, screening continued, and 52 out of 104 older adults were found eligible to participate. Eight participants withdrew from the baseline assessment due to COVID-related reasons and refused to undergo face-to-face assessment. (Fig. 1).

Table 3 shows a total of 52 participants included in this study, randomised into the experimental group (WE-SURF™) (n = 26) and control group (n = 26). Majority of the participants were women (85%), Chinese (52%), unmarried/ windowed/divorced (71%) and with secondary education level (60%). Please note that three female participants (intervention: one; control: two) have a history of lower limb fracture within the past three to 10 years.

The results (Table 4) showed significant time x group interaction effects on risk of falls (TUG, p < 0.05), lower and upper limbs muscle strength (5STS & HGS) and balance (SLS). The experimental versus the control group showed greater improvements in the percentage mean change in SLS (111% vs 42%), 5STS (− 32% vs − 16%), TUG (− 27% vs − 17%) and dominant HGS (10% vs − 1%).

Feasibility outcomes

The average of total attendance rate of the exercise program exceeded 81% (attended 39 out of 48 sessions). A total of 96% of the participants completed the study after 24 weeks. Eighty three percent of the participants recorded an absence for at least one session and the frequency of missed sessions ranged from one to eight. The common reasons for absence were COVID-19 vaccine appointments, resting after vaccine shot, personal commitments, and travelling. One of the adverse outcomes recorded was mild musculoskeletal related pain, experienced by nine older adults involving either the shoulder, ankle, low back and knee after the exercise program. Notably, all these participants had preexisting musculoskeletal pain disorders, such as ankle swelling, frozen shoulder, low back pain, and knee osteoarthritis. Moreover, upon further questioning, all the participants asserted that their musculoskeletal pain was not related to the virtual exercise and reported a reduction in pain upon completion compared to the initial session of the program.

The majority of participants scored 8/10 for exercise levels 1 and 2, while at level 3, it was 9/10, with a mean ranging from 7/10 to 9/10. Multiple interruptions occurred during virtual exercise sessions, including disturbances by pets (5 sessions), playful grandchildren (10 sessions), arguments with spouses (15 sessions), multitasking (7 sessions), visits to the toilet (15 sessions), and office work (12 sessions).

At the 6-month follow-up visit, four participants from the intervention group and three from the control group experienced at least one fall; however, it’s noteworthy that these falls did not occur during the exercise sessions. Two female participants from each group experienced mild musculoskeletal injuries (intervention: elbow and low back pain; control group: both had low back pain), lasting for a week due to falling, while three others had no complaints post-fall.

Discussion

The WE- SURF™ exercise program appears to be acceptable and feasible among community-dwelling older adults with low and moderate risk of falls without any severe adverse events. While prior experience with virtual classes had been limited among older adults, this did not appear to limit their ability to participate in the virtual exercise program developed within this study. In a previous study conducted among pre-disabled older adults, good satisfaction level towards remote exercise program was reported [55]. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of virtual exercise options, even among older adults who may not be considered technologically savvy [56, 57].

Safety of the older adults was the main concern in this study. Strict adherence to selection criteria was therefore practiced, whereby only those who were able to stand on one leg for more 10 s were included. As exercise program contained a balance challenge component, the prevention of a fall during exercise is vital to ensure continuation of the study and participant safety [58, 59]. Technology gadgets utilised by participants in this study consisted of the lowest range (low specification smartphone) to desktops with high processing speeds, which was similar to the findings from a previous study [60]. Smaller screen, low volume, and internet interruption were the common challenges reported in the preliminary test. However, these challenges are seldom reported in previous studies, probably because smartphones were used by many among the present study compared to other studies in the western countries [60, 61].

The high attendance and low dropout rates could be explained by the motivation techniques used in this study. A social media messaging group was created for each block of participant groups (total of 4 groups) and this led to a sense of belonging, connection, friendship among them with greetings, discussions about exercise, sharing of hobbies, and consultation about personal health conditions with the instructor. A similar technique has been reported previously [33]. In addition, the real time supervision and interaction between participants and instructor formed a dynamic interaction and an enjoyable atmosphere in the virtual environment.

Despite some musculoskeletal problems, participants were able to complete the program. It is noteworthy that the instructor, a physiotherapist with experience in geriatric physiotherapy played an active role in providing consultation regarding any problems encountered by the participants. For instance, self-management techniques with modifications to the exercise was provided to facilitate quick relief and continuous participation. Likewise, monitoring the perceived exertion level using Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scores from each participant during and after exercise sessions was advantageous in providing feedback from participants for exercise adaptations by the instructor. Intensity of exercises started with “light” (as in Borg Rating of perceived exertion level) and progressed to higher levels over the 3 month period. This could have led to higher engagement rates in level three compared to the first level of the exercise program as reported in previous related studies [62, 63]. Lastly, no fall or any other related injury occurred during the exercise session among participants in our present study.

The WE-SURF™ program was shown to be effective in improving balance and muscle strength. These findings suggest that similar results are possible even via virtual falls prevention exercises programs among older adults. This is expected as the program was designed based on evidence based fall prevention recommendations [19, 64]. WE-SURF™ fulfilled the requirements of exercise intensity of total 60 h, being multicomponent, combining challenging balance, resistance, aerobic, backward chaining and square stepping training [21, 65, 66]. In previous falls prevention programs that were conducted physically, it was demonstrated that there was an improvement in balance and muscle strength [67,68,69,70]. However, further studies are required to evaluate quality of life and fear of falls pertaining to virtual exercise programs. Longer interventions with inclusion of fear alleviating techniques may be required in such programs.

This study was limited by its execution during the COVID-19 pandemic which could have led to a higher acceptance and adherence rate resulting from the lack of any other competence engagement due to lock down and shielding which occurred among older adults. Further, while the exercise equipment such as a specially designed square-stepping mat, strap on weights and yoga mats were of low cost, it could limit its implementation especially among older adults from lower socio-economic groups. In addition, the requirement of an experienced physiotherapist as an instructor may not be possible for sustainability of such programs. However, knowledge transfer and echo training and step by step guide via digitalization are plausible for such programs to be maintained among older adults.

Conclusion

In conclusion, WE-SURF™, a virtual supervised group-based fall prevention exercise program demonstrated acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness among community-dwelling older adults with mild to moderate risk of falls, showing improvements in balance and lower limb muscle strength. Further research is needed to evaluate the implementation of the WE-SURF™ program as a fall’s prevention program among older adults, explore its long-term effects, and assess its impact on quality of life and fear of falling.

Data availability

All data available is shared in this paper.

References

Bong May Ing J et al (2023) Group-based exercise interventions for community-dwelling older people in Southeast Asia a systematic review. Australas J Ageing 42:624–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.13227

Montero-Owasso M et al (2022) World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing 51:1–36

Salary N, Darvish N, Ahmadian M et al (2022) Global prevalence of falls in the older adults : a comprehensive systematic review and meta—analysis. J Orthoepy Surg Res 1:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03222-1

Yeong UY, Tan SY, Yap JF et al (2016) Prevalence of falls among community-dwelling elderly and its associated factors: a cross-sectional study in Perak, Malaysia. Malays Fam Physician 11:7–14

Lim KH et al (2014) Risk factors of home injury among elderly people in Malaysia. Asian J Gerontol Geriatr 9:16–20

Salina S, Rajma K (2008) Prevalence of falls among older people attending a primary care clinic in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Malay J Community Health 14:11

Ooi TC et al (2021) Incidence and multidimensional predictors of occasional and recurrent falls among Malaysian community-dwelling older persons. BMC Geriatric 21:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02103-2

Ibrahim A, Ajith DKS, Shahar S et al (2017) Timed up and go test combined with self-rated multifactorial questionnaire on falls risk and sociodemographic factors predicts falls among community-dwelling older adults better than the timed up and go test on its own. J Multidisc Healthc 10:409–416. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S142520

Singh DKA, Shahar S, Vanoy D et al (2019) Diabetes, arthritis, urinary incontinence, poor self-rated health, higher body mass index and lower handgrip strength are associated with falls among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: Pooled analyses from two cross-sectional Malaysian datas. Geriatr Gerontol Int 19:798–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13717

Ooi TC et al (2021) Incidence and multidimensional predictors of occasional and recurrent falls among Malaysian community-dwelling older persons. BMC Geriatr 21:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02103-2

James SL et al (2019) The global burden of falls global, regional and national estimates of morbidity and mortality from the global burden of disease study 2017. Inj Prev 26:3–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043286

Montero-Odasso M et al (2022) World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing 51:1–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac205

Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F et al (2010) Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 21:658–668. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905

Smee DJ, Anson JM, Waddington GS et al (2012) Association between physical functionality and falls risk in community-living older adults. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res 2012:864516. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/864516

C. Todd and D. Skelton (2004) What are the main risk factors for falls amongst older people and what are the most effective interventions to prevent these falls?. World Health 28.

Win AM, Yen LW, Tan KH et al (2015) Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior in a representative sample of a multi-ethnic South-East Asian population: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 15:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1668-7

Ibrahim A, Singh DKA, Shahar S (2017) ‘Timed up and go’ test: age, gender and cognitive impairment stratified normative values of older adults. PLoS ONE 12:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185641

Gomes M et al (2017) Physical inactivity among older adults across Europe based on the SHARE database. Age Ageing 46:71–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw165

Sherrington C et al (2017) Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 51:1749–1757. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096547

Sherrington C et al (2019) Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019:885–891. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2

Chang M, Huang YH, Jung H (2011) The effectiveness of the exercise education programme on fall prevention of the community-dwelling elderly: a preliminary study. Hong Kong J Occup Ther 21:56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkjot.2011.10.002

Lee DCA, Pritchard E, McDermott F et al (2014) Falls prevention education for older adults during and after hospitalization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Educ J 73:530–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896913499266

Nokham R, Kitisri C (2017) Effect of square-stepping exercise on balance in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Phys Fit Sports Med 6:183–190. https://doi.org/10.7600/jpfsm.6.183

Shigematsu R et al (2008) Square-stepping exercise and fall risk factors in older adults: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Gerontology A Biol Sci Med Sci 63:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/63.1.76

Leonhardt R, Becker C, Groß M et al (2020) Impact of the backward chaining method on physical and psychological outcome measures in older adults at risk of falling: a systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res 32:985–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01459-1

Avers D (2010) Community-based exercise programs for older adults. Top Geriatr Rehabil 26:275–298. https://doi.org/10.1097/TGR.0b013e318204b029

Horton K, Dickinson A (2011) The role of culture and diversity in the prevention of falls among older Chinese people. Can J Aging 30:57–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980810000826

Östh J et al (2019) Effects of yoga on well-being and healthy ageing: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (FitForAge). BMJ Open 9:e027386. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027386

Rivera-Torres S, Fahey TD, Rivera MA (2019) Adherence to exercise programs in older adults: informative report. Gerontol Geriatr Med 5:233372141882360. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721418823604

Loganathan A, Ng CJ, Low WY (2016) Views and experiences of Malaysian older persons about falls and their prevention—a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr 16:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0274-6

Pettersson B et al (2019) ’Managing pieces of a personal puzzle’-Older people’s experiences of self-management falls prevention exercise guided by a digital program or a booklet 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. BMC Geriatr 19:1–12

Mazuz K, Biswas S, Lindner U (2020) Developing self-management application of fall prevention among older adults: a content and usability evaluation. Front Digit Health 2:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2020.00011

Ibrahim A, Chong MC, Khoo S et al (2021) Virtual group exercises and psychological status among community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic- a feasibility study. Geriatrics 6:31. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6010031

MdFadzil NH et al (2023) Digital technology usage among older adults with cognitive frailty: a survey during COVID-19 pandemic. Digit Health 9:594. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231207594

Chan JKY, Klainin-Yobas P, Chi Y et al (2021) The effectiveness of e-interventions on fall, neuromuscular functions and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 113:103784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103784

El Maniani M, Rechchach M, El Mahfoudi A et al (2016) A Calorimetric investigation of the liquid bi-ni alloys. J Mater Environ Sci 7:3759–3766

Din NC, Shahar S, Zulkifli BH et al (2016) Validation and optimal cut-off scores of the bahasa malaysia version of the montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA-BM) for mild cognitive impairment among community dwelling older adults in Malaysia. Sains Malays 45:1337–1343

Olsen O, Sjøhaug M, Van Beekvelt M et al (2012) The effect of warm-up and cool-down exercise on delayed onset muscle soreness in the quadriceps muscle: a randomized controlled trial. J Hum Kinet 35:59–68. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10078-012-0079-4

WHO (2016) WHO Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour.

Ng CACMCM, Fairhall N, Wallbank G et al (2019) Exercise for falls prevention in community-dwelling older adults: trial and participant characteristics, interventions and bias in clinical trials from a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 5:e000663. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000663

Moore DS et al (2008) Construct validation of physical activity surveys in culturally diverse older adults: a comparison of four commonly used questionnaires. Res Q Exerc Sport 79:42–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2008.10599459

Tebar WR et al (2022) Validity and reliability of the Baecke questionnaire against accelerometer measured physical activity in community dwelling adults according to educational level. PLoS ONE 17:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270265

Nikmat AW, Azhar ZI, Shuib N et al (2021) Psychometric properties of geriatric depression scale (Malay version) in elderly with cognitive impairment. Malays J Med Sci 28:97–104. https://doi.org/10.21315/MJMS2021.28.3.9

Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L (2002) Berg balance scale, timed up & go. Phys Ther 82:128–137

Ponce-González JG, Sanchis-Moysi J, González-Henrlquez JJ et al (2014) A reliable unipedal stance test for the assessment of balance using a force platform. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 54:108–117

Villafañe JH, Valdes K, Buraschi R et al (2016) Reliability of the handgrip strength test in elderly subjects with parkinson disease. Hand 11:54–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558944715614852

Bohanno RW (2011) Test-retest reliability of the five-repetition sit-to-stand test: a systematic review of the literature involving adults. J Strength Cond Res 25:3205–3207. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318234e59f

Shafique S, Ahmad S, Shakil-Ur-Rehman S (2019) Effect of Mulligan spinal mobilization with arm movement along with neurodynamics and manual traction in cervical radiculopathy patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Pak Med Assoc 69:1601–1604. https://doi.org/10.5455/JPMA.297956

Van Leeuwen KM et al (2015) Comparing measurement properties of the EQ-5D-3L, ICECAP-O, and ASCOT in frail older adults. Value in Health 18:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2014.09.006

Kempen GIJM et al (2008) The Short FES-I: A shortened version of the falls efficacy scale-international to assess fear of falling. Age Ageing 37:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afm157

Dewan N, MacDermid JC (2014) Fall efficacy scale—international (FES-I). J Physiother 60:60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2013.12.014

Tan MP, Nalathamby N, Mat S et al (2018) Reliability and validity of the short falls efficacy scale international in English, Mandarin, and Bahasa Malaysia in Malaysia. Int J Aging Hum Dev 87:415–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415017752942

Efird J (2011) Blocked randomization with randomly selected block sizes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8:15–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8010015

Maher C, Hadfield M, Hutchings M et al (2018) Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: a design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. Int J Qual Methods 17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918786362

Buckinx F et al (2021) Feasibility and acceptability of remote physical exercise programs to prevent mobility loss in pre-disabled older adults during isolation periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nutr Health Aging 25:1106–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-021-1688-1

Derynda B, Siegel J, Maurice L et al (2022) Virtual lifelong learning among older adults: usage and impact during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus 14:e24525. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.24525

Diehl C et al (2022) Perceptions on extending the use of technology after the covid-19 pandemic resolves: a qualitative study with older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19:14152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114152

Ho H-H et al (2021) Is functional fitness performance a useful predictor of risk of falls among community-dwelling older adults? Archives of Public Health 79:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00608-1

Sh L, Hh C, Ey R et al (2020) Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency treatment in patients with refractory chronic cervical radicular pain. Pain Physician 23:E265–E272

Li F, Harmer P, Voit J (2021) Implementing an online virtual falls prevention intervention during a public health pandemic for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a feasibility trial. Clin Interv Aging 16:973–983

Baez M, Far IKIK, Ibarra F et al (2017) Effects of online group exercises for older adults on physical, psychological and social wellbeing: a randomized pilot trial. PeerJ 2017:1–27. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3150

Baker BS et al (2021) Efficacy of an 8-week resistance training program in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Aging Phys Act 29:121–129. https://doi.org/10.1123/JAPA.2020-0078

Kim S, Lockhart T (2010) Effects of 8 weeks of balance or weight training for the independently living elderly on the outcomes of induced slips. Int J Rehabil Res 33:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e32832e6b5e

Montero-Odasso M et al (2021) New horizons in falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing 50:1499–1507. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab076

Hyun J, Hwangbo K, Lee CW (2014) The effects of pilates mat exercise on the balance ability of elderly females. J Phys Ther Sci 26:291–293. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.291

Pinheiro MB, Oliveira J, Bauman A et al (2020) Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65+ years: a systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 17:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01040-4

Sitthiracha P, Eungpinichpong W, Chatchawan U (2021) Effect of progressive step marching exercise on balance ability in the elderly: a cluster randomized clinical trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063146

Thompson C, Holskey T, Wallenrod S et al (2019) Effectiveness of a fall prevention exercise program on falls risk in community-dwelling older adults. Transl J Am Coll Sports Med 4:16. https://doi.org/10.1249/TJX.0000000000000078

Okubo Y, Schoene D, Lord SR (2017) Step training improves reaction time, gait and balance and reduces falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 51:586–593. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095452

Chittrakul J, Siviroj P, Sungkarat S et al (2020) Multi-system physical exercise intervention for fall prevention and quality of life in pre-frail older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093102

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the research participants, and and family members for participation in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JBMI and DKAS contributed to the study conception and design. JBMI performed material preparation. IKT and JBMI performed data collection and analysis. JBMI and DKAS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MPT and JW reviewed and commented on the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of human and animal rights

Human research ethics approval was obtained through the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the University (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (JEP-2020-611) and the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Malaysia (NMRR-20–2289-56760). The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (Registration number: ACTRN 12621001620819).

Informed consent

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ing, J.B.M., Tan, M.P., Whitney, J. et al. Acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of WE-SURF™: a virtual supervised group-based fall prevention exercise program among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res 36, 125 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02759-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02759-x