Abstract

Purpose

This research identified whether adolescent religiosity was associated with body satisfaction and disordered eating in adolescence and early adulthood and explored gender/sex differences in these associations.

Methods

Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults) is a longitudinal cohort study following participants from adolescence into young adulthood. For this analysis (N = 1620), religiosity (importance of religion and frequency of religious service participation) during adolescence was examined as a correlate of body satisfaction and disordered eating (binge eating, maladaptive behaviors intended to lose or maintain weight, eating to cope, and dieting) at the same life stage (EAT-II, 2003–2004, Mage = 19.4 years) and during young adulthood (EAT-IV, 2015–2016, Mage = 31.5 years). Analyses used linear and logistic regression models adjusted for demographics and adolescent body mass index.

Results

During adolescence, females who placed greater importance on religion had higher body satisfaction, 22% higher odds of binge eating, and 19% greater odds of dieting in the past year, while more frequent attendance of religious services was associated with higher body satisfaction and 37% greater odds of dieting past year. Among males, only frequent attendance of religious services was associated with higher adolescent body satisfaction. Longitudinally, among females, only frequent attendance of religious services in adolescence predicted higher levels of body satisfaction in young adulthood. No significant longitudinal associations were observed among males.

Conclusions

Our findings contribute to understanding the complex interplay between religiosity, gender, and body satisfaction. Further research should explore cultural factors influencing these associations and qualitative aspects of religious experiences to inform nuanced interventions.

Level of evidence: Level III, cohort study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Religion plays an important role in the lives of many individuals around the world [1, 2]. Religiosity encompasses individuals’ engagement in religious rituals and practices associated with a higher power or a specific faith [3]. Research suggests religion and spirituality can positively influence overall health and well-being by encouraging the adoption of a range of health-promoting religious practices [4, 5]. For instance, meditation and prayer are known to reduce stress and improve mental health, while active participation in community life strengthens social networks and support systems [4]. Moreover, religious teachings often emphasize values and a sense of purpose, advocate for a balanced lifestyle, and promote moderation and healthy living habits [4]. Many religions consider the human body sacred and impose specific restrictions on unhealthy behaviors such as overeating, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption, deeming them both physically and spiritually harmful [4]. These perspectives highlight the interplay between physical, mental, and spiritual well-being. Previous research has examined the influence of religiosity on various health dimensions. Studies showed associations between religiosity and dietary behaviors [6,7,8], weight status [6, 9,10,11,12], mental health [5, 13], overall health promotion [9, 14, 15], and disease prevention [14, 15].

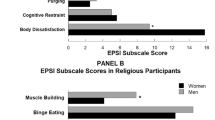

Numerous studies have investigated the relationship between religiosity and various aspects of body satisfaction and disordered eating, yielding a range of results. For example, a systematic review of 22 studies examining the relationship between religiosity/spirituality and disordered eating yielded mixed associations: six studies reported positive effects, four found negative effects, two showed mixed results, and three found no significant associations. In contrast, among 15 studies that examined religiosity/spirituality and body image, 12 noted positive associations [16]. The existing literature also showed inconsistent gender differences in these associations. For example, a cross-sectional study (68% women) found that body satisfaction in older men was positively associated with religious and existential well-being, whereas in older women, it was only linked to existential well-being [17]. Another cross-sectional study (72% women) showed that religious men had higher levels of purging, restricting, muscle-building behaviors, and negative attitudes towards higher weight status than religious women [18]. However, both religious women and men displayed similar levels of body dissatisfaction and binge eating. Conversely, two Canadian studies concurrently found no significant link between religiosity and body satisfaction or bulimia among Canadian women with ethnically diverse backgrounds [19, 20]. These studies, most of which were cross-sectional, have often relied on predominantly female adult samples and yielded inconsistent results [16,17,18,19,20,21], highlighting the need for further research to explore potential gender differences and the varying influence of religiosity on body image and disordered eating behaviors.

Building on these studies, the current study expands the extant literature to learn more about how religiosity may be related to body satisfaction and disordered eating among both females and males. The purpose of this present study is to explore in a population-based sample: (1) associations between religiosity in adolescence and body satisfaction and disordered eating (binge eating, eating to cope, maladaptive behaviors intended to lose or maintain weight, dieting) in both adolescence and young adulthood and (2) gender/sex differences in these associations. A hypothesis has not been made due to the inconsistencies in the literature to date. Findings will help public health professionals and researchers to understand the nuanced relationship between religious beliefs/practices, body image, and disordered eating across genders over time, providing important insights for creating targeted health interventions.

Methods

Study design and sample

This study used data from the Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults) study. Project EAT is a 15-year longitudinal, population-based cohort study focusing on behavioral, psychological, and socioenvironmental factors influencing dietary intake, physical activity, and weight-related outcomes in adolescents and young adults [22,23,24,25]. The data presented in this manuscript are derived from the follow-up surveys conducted in two waves: the earlier follow-up in 2003–2004 (EAT-II) and the latest follow-up in 2015–2016 (EAT-IV). During the 2003–2004 follow-up, we identified the contact details for 3,672 participants out of the original cohort of 4,746 (EAT-I, 1998–1999), receiving 2,516 completed surveys as a result of a mailing campaign (mean age = 19.4 ± 1.7 years), representing a 68.4% response rate. For the 2015–2016 follow-up, the survey was sent out to those original 1998–1999 participants who had completed at least one prior follow-up survey. From the available contact information for 2,770 individuals, we gathered data online, by mail, or by phone, achieving a 66.1% response rate and obtaining completed surveys from 1,830 young adults with an average age of 31.0 years (SD = 1.6). Overall, more than 88% of the individuals in the EAT-IV cohort had also completed the 2003–2004 mailed survey (n = 1,620), which constitutes the analytical sample for the present study. Study protocols were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. In 1998–1999, participants provided their written assent. For follow-up surveys, each participant received a consent form either included with mailed surveys or presented at the start of the online survey. By completing and returning the survey, participants implicitly indicated their consent to participate in the study.

Survey development

Key items from earlier study waves (Projects EAT-I, II, and III) were retained in the Project EAT-IV survey to facilitate longitudinal assessments and explore secular trends. The scale's psychometric properties were assessed using the entire EAT-IV sample. The item test–retest reliability estimates were utilized from a subgroup of 103 respondents who completed the survey twice in a time frame of 1–4 weeks [22]. In this study, two religiosity questions (importance of religion and frequency of religious service participation) were used as the primary predictors, which were only collected during the Project EAT-II (2003–2004) wave. Prior to being included in the Project EAT-II survey, the research team pretested the questions about the frequency of religious service attendance and the significance of religion with 20 young adults in focus groups. Young people who participated in pretesting completed a prefinal version of the survey on their own, and then they discussed the survey’s content, question phrasing, and response possibilities as a group.

Religiosity

Adolescent religiosity was examined by two separate questions (developed for the Project EAT study) regarding attitudes towards religion and religious practices: (1) how important is religion to you? with a four-point scale ranging from ‘not at all = 1’ to ‘very = 4’ and (2) how often do you attend religious services? with response options ‘never = 1,’ ‘rarely = 2,’ ‘once or twice a month = 3,’ and ‘about once a week or more = 4.’ Based on the median value of response options, the importance of religion (median = 3) was dichotomized as greater importance (very and moderately) and less importance (somewhat and not at all), while the frequency of religious service participation (median = 2) was dichotomized as more frequent participation (once or twice a month, and about once a week or more) and less frequent participation (never and rarely). Dichotomized versions of religiosity variables were used in the demographic characteristics of the participants to outline the sample. Meanwhile, continuous religiosity variables were employed in the regression models to explore the association between religiosity, body satisfaction, and disordered eating among both females and males.

Body satisfaction

In a modified version of the Body Shape Satisfaction Scale [26], participants reported their satisfaction (in both adolescence and young adulthood) with 13 different body parts (height, weight, body shape, waist, hips, thighs, stomach, face, body build, shoulders, muscles, chest, and overall body fat) on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’ (α = 0.94; test–retest reliability = 0.82).

Disordered eating behaviors

Binge eating

Two questions assessed binge eating during adolescence and young adulthood (sources of the questions: [27,28,29]): “In the past year, have you ever eaten so much food in a short period of time that you would be embarrassed if others saw you (binge eating)?” and “During the times (past year) when you ate this way, did you feel you couldn’t stop eating or control what or how much you were eating?” with ‘yes’ and ‘no’ response options. Participants were classified as ‘yes’ if they reported any binge eating and ‘no’ if they reported no binge eating behaviors (test–retest agreement = 90%).

Eating as a coping strategy

To examine eating as a coping strategy in young adulthood, participants were asked to complete a 5-item Coping Subscale of the Motivations to Eat Measure [30] with response options ‘almost never or never,’ ‘rarely,’ ‘sometimes,’ ‘often,’ and ‘almost always or always’ (α = 0.92; test–retest reliability = 0.76). The 5-item in the Coping Subscale of the Motivations to Eat Measure includes eating due to feeling depressed or sad, worthless or inadequate, as a way to cope, receive comfort, and for distraction. In adolescence, eating as a coping strategy was not examined.

Maladaptive behaviors intended to lose or maintain weight

Maladaptive behaviors intended to lose or maintain weight during adolescence and young adulthood were examined by asking participants, “Have you done any of the following things in order to lose weight or keep from gaining weight during the past year?: engaged in fasting, ate very little food, used diuretics, laxatives, or a food substitute (e.g., powder or special drink), skipped meals, smoked more cigarettes, took diet pills, or induced vomiting.” Response options included ‘yes’ and ‘no’ [31, 32]. Participants were classified as engaging in maladaptive behaviors intended to lose or maintain weight if they endorsed one or more maladaptive behaviors intended to lose or maintain weight (test–retest agreement = 86%) [22].

Dieting

During adolescence, participants were asked, “How often have you gone on a diet during the last year?” with response options ‘never,’ ‘1–4 times,’ ‘5–10 times,’ ‘more than 10 times,’ and ‘I am always dieting.’ Response options were dichotomized as no (never) and yes (other responses) (test–retest agreement = 89%) [33, 34]. In young adulthood (EAT-IV), participants were asked, “Have you gone on a diet to lose weight during the last year?” with response options ‘yes’ and ‘no’ (test–retest agreement = 92%).

Demographic characteristics

Participants’ age, sex, ethnicity/race, body weight, and height were measured via self-reports on the survey during adolescence. Socioeconomic status (SES) at EAT-I [1(lowest)—5 (highest)] was derived based on parental education level, parental job status, public assistance eligibility, and access to free or reduced-cost meals at schools, consistent with other EAT studies [35, 36]. Participants’ body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

The religions in which participants were raised were examined by one question adapted from College Alcohol Study [37, 38], “In what religion were you raised?” with response options ‘none,’ ‘Buddhism,’ ‘Catholicism,’ ‘Islam,’ ‘Judaism,’ ‘Protestantism,’ ‘Shamanism,’ and ‘other.’

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics used dichotomized versions of religiosity variables (importance of religion and frequency of religious service participation). Chi-square, Fisher exact tests, and t tests were used to assess the associations between demographics and religiosity.

To examine the cross-sectional associations between religiosity and body satisfaction and disordered eating in adolescence, gender-stratified adjusted linear and logistic regression models were used. Models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, SES, and BMI during adolescence.

Gender-stratified adjusted logistic regressions and linear regressions were also used to assess whether religiosity in adolescence longitudinally predicted body satisfaction and disordered eating in young adulthood. Models adjusted for race/ethnicity, SES, and BMI in adolescence and age in young adulthood.

All analyses were performed in R (version 4.3.1; R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data were weighted using the inverse of the estimated probability of a participant responding at both the 2003–2004 and the 2015–2016 because the attrition did not occur randomly from EAT-I [39]. This approach allowed for the weighted sample to reflect the demographic composition of the original school-based cohort more accurately, thus enhancing the ability to extrapolate the findings to the broader population of adolescents residing in the Minneapolis–St. Paul metropolitan area during the 1998–1999 period.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents by religiosity

During adolescence, participants were equally divided on gender/sex and identified as having been raised in a variety of religious traditions (see Table 1). Adolescents’ age, gender/sex, race/ethnicity, religion, and frequency of religious service participation differed by religious importance. More males (53.4%) reported greater religious importance compared to females (46.6%; p = 0.01). Religious service attendance was associated with age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, and religious importance (Table 1).

Cross-sectional associations between religiosity and body satisfaction and disordered eating during adolescence by gender/sex

Among females, religiosity was cross-sectionally associated with body satisfaction and two disordered eating in adolescence in analyses adjusted for adolescent age, SES, race/ethnicity, and BMI (Table 2). Specifically, higher importance of religion during adolescence was associated with higher body satisfaction (β: 0.70; 95% CI 0.18, 1.21); 22% higher odds of past-year binge eating (95% CI 1.02, 1.47); and 19% greater odds of past-year dieting (95% CI 1.04, 1.37). On the other hand, more frequent religious service attendance was associated with higher body satisfaction (β: 0.67; 95% CI 0.12, 1.22) and 37% greater odds of past-year dieting (95% CI 1.18, 1.59). Among males, the only significant cross-sectional association found among males was that a higher frequency of religious service attendance was associated with greater body satisfaction in adolescence (β: 0.77; 95% CI 0.14, 1.40) after adjusting analysis for adolescent age, SES, race/ethnicity, and BMI (Table 2).

Longitudinal associations between religiosity in adolescence and body satisfaction and disordered eating in young adulthood by gender/sex

In unadjusted models, our analysis showed no significant associations between the levels of religiosity in adolescence and body satisfaction or the prevalence of disordered eating in young adulthood when examining females and males separately (Data not shown).

Among female participants, in analyses adjusted for age in young adulthood and socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, SES, and BMI at adolescence, more frequent religious service participation in adolescence was associated with higher body satisfaction (β: 0.67; 95% CI 0.11, 1.23) in young adulthood (Table 3). However, there was no significant association between religiosity in adolescence and any disordered eating in young adulthood among females. Among male participants, there were no associations between religiosity in adolescence and body satisfaction and disordered eating in young adulthood (Table 3).

Discussion

The current study assessed cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between religiosity in adolescence and body satisfaction and disordered eating behavior outcomes in both adolescence and young adulthood among a diverse, population-based sample. In adjusted cross-sectional models, we found female adolescents who placed higher importance on religion and attended religious services more frequently reported higher body satisfaction and were more likely to binge eat or diet, while those attending religious services more frequently were also more likely to diet. Among male adolescents, frequent religious service attendance was associated with higher adolescent body satisfaction. In adjusted longitudinal models, we found more frequent religious service participation during adolescence predicted higher body satisfaction a decade later among females but not disordered eating. Conversely, adolescent religiosity did not significantly predict body satisfaction or disordered eating in young adulthood among males. Overall, some of the findings were not consistent across analyses nor in consistent directions (e.g., higher body satisfaction but higher levels of dieting).

The cross-sectional finding indicates that higher religiosity (characterized by placing higher importance on religion and more frequent religious service attendance) was associated with greater body satisfaction in adolescence among females. These positive associations between religiosity and body satisfaction align with the work of Kim [40], who showed that women who spent more time in religious activities had greater body satisfaction [40]. Similarly, Homan and Cavanaugh (2013) found that a strong, warm, and secure connection with one’s God was associated with higher body appreciation among young women in their cross-sectional analysis [41]. While these findings underscore the potential benefits of religious and spiritual community support systems for women’s body image and well-being, it is essential to interpret them with caution because we did not see associations with most of the outcomes, and the direction of the findings varied across different analyses. Nonetheless, these insights suggest the potential value of fostering supportive environments within religious communities that prioritize overall well-being and acceptance. Identifying and addressing any underlying societal ideologies or cultural pressures that may inadvertently contribute to body dissatisfaction is crucial in creating nurturing spaces where women feel empowered to embrace their bodies.

The present study showed that higher religiosity was associated with higher body satisfaction and higher odds of dieting among females during adolescence. This dual-faceted influence of religiosity on body satisfaction and dieting may have also been influenced by other variables, such as cultural, familial, or societal attitudes [42, 43], which could interplay with individual religious beliefs in complex ways. For example, many religions advise modesty in dress [44], which can influence body satisfaction positively by reducing exposure to idealized body types. However, societal factors such as media exposure emphasizing thinness or familial practice of frequent discussions on appearance, thinness, eating, and/or weight could lead to dieting and increase pressure to conform to specific body standards [45,46,47]. Thus, these findings call for a deeper exploration into the other factors and types of religious messages about the body in different religions practiced during adolescence and how they may shape long-term attitudes and behaviors related to body image and eating behaviors.

For males and females, cross-sectional analyses indicated a positive association between religious service attendance and body satisfaction. This cross-sectional association persists into young adulthood among females but not among males. The initial association might reflect greater stability in the family or a sense of belonging to religious community life during adolescence [43, 48], which could contribute to better body satisfaction. Yet, in adulthood, other factors likely become more influential for male body image [49], potentially overshadowing the early influence of religious community engagement. Specific factors such as evolving social norms, individual identity development, and changing perceptions of masculinity may shape whether religiosity positively or negatively influences body image. Further investigation into these nuanced dynamics is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between religiosity and body image across the lifespan.

It is important to interpret our findings in light of the study’s limitations. Our survey assessed religiosity only at one point in time and utilized only three questions. Future research would benefit from a more detailed evaluation of religiosity, including assessing religiosity over time. We also had limited power to detect differences across religions. While our study focused on adolescents’ religiosity, it is essential to recognize that their attendance at religious services may be shaped by parental factors, such as upbringing, family values, and parental encouragement. In addition, being involved in religious activities can contribute to body satisfaction because young people may feel a sense of community and belonging not related to the religious aspects of their experiences. Moreover, the importance of religion and the frequency of religious service attendance questions were not from a validated scale. The current study also has important strengths. First, the study’s large ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample enhances the ability to generalize results to broader groups of adolescents and young adults. In addition, the longitudinal study design allowed examination of the predictive nature of religiosity, with our follow-up period notably longer than that of prior studies to the best of our knowledge.

Our findings highlight the complex relationship between personal faith practices in youth and perceptions of body satisfaction in adolescence and young adulthood. Although adolescent religious service attendance may positively influence body satisfaction during young adulthood for some females, this association was not found among males. Therefore, these gender/sex differences show that public health initiatives within religious settings should be approached carefully and thoughtfully, with an emphasis on promoting a healthy body image. It is important to explore whether training for clergy, youth directors, or the wider public would be valuable, taking care to avoid any unintended negative consequences. Further research is vital to deepening an understanding of cultural norms, traditions, values, and practices within different religious groups, as well as the qualitative aspects of religious experiences to provide deeper insights into the inconsistencies observed in quantitative analyses as well as to enhance the effectiveness of interventions targeting diverse faith communities. This considered approach should prioritize cultural sensitivity and avoid any potential harm in its application.

What is already known on this subject?

Religiosity plays a significant role in many people’s lives, influencing their beliefs, behaviors, and overall well-being. In many religions, the body is considered sacred, and certain behaviors that are harmful, both physically and spiritually, are discouraged. However, existing research, often based on cross-sectional studies, presents mixed findings regarding the influence of religiosity on body satisfaction and disordered eating in both females and males.

What this study adds?

This study advances our understanding of how religiosity in adolescence relates to body satisfaction in adolescence and young adulthood, especially among females. These findings have the potential to benefit public health professionals and researchers by contributing to the development of targeted interventions focused on promoting body satisfaction within religious communities.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tamir C, Connaughton A, Salazar AM (2020) The global God divide. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

Smith GA, Cooperman A, Mohamed B et al (2015) U.S. public becoming less religious. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

Tanyi RA (2002) Towards clarification of the meaning of spirituality. J Adv Nurs 39:500–509. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1365-2648.2002.02315.X

Ellison CG, Levin JS (1998) The religion-health connection: evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Educ Behav 25:700–720

Weber SR, Pargament KI (2014) The role of religion and spirituality in mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry 27:358–363. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000080

Tan M-M, Chan CKY, Reidpath DD (2014) Faith, food and fettle: Is individual and neighborhood religiosity/spirituality associated with a better diet? Religions 5:801–813. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel5030801

Tan M-M, Chan CKY, Reidpath DD (2016) Religiosity, dietary habit, intake of fruit and vegetable, and vegetarian status among Seventh-Day Adventists in West Malaysia. J Behav Med 39:675–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9736-8

Tan M-M, Chan CKY, Reidpath DD (2013) Religiosity and spirituality and the intake of fruit, vegetable, and fat: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2013:146214. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/146214

Reeves RR, Adams CE, Dubbert PM et al (2012) Are religiosity and spirituality associated with obesity among African Americans in the Southeastern United States (the Jackson Heart Study)? J Relig Health 51:32–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9552-y

Yeary KH, Cheon K, Sobal J, Wethington E (2017) Religion and body weight: a review of quantitative studies. Obesity Rev 18:1210–1222. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12569

Bharmal N, Kaplan RM, Shapiro MF et al (2013) The association of religiosity with overweight/obese body mass index among Asian Indian immigrants in California. Prev Med 57:315–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.003

Bruce MA, Beech BM, Wilder T et al (2020) Religiosity and excess weight among African-American adolescents: the Jackson Heart KIDS study. J Relig Health 59:223–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00762-5

Lucchetti G, Koenig HG, Lucchetti ALG (2021) Spirituality, religiousness, and mental health: a review of the current scientific evidence. World J Clin Cases 9:7620–7631. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7620

Mishra SK, Togneri E, Tripathi B, Trikamji B (2017) Spirituality and religiosity and its role in health and diseases. J Relig Health 56:1282–1301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0100-z

Brewer LC, Bowie J, Slusser JP et al (2022) Religiosity/spirituality and cardiovascular health: the American Heart Association Life’s Simple 7 in African Americans of the Jackson Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc 11:e024974. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.121.024974

Akrawi D, Bartrop R, Potter U, Touyz S (2015) Religiosity, spirituality in relation to disordered eating and body image concerns: a systematic review. J Eat Disord 3:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0064-0

Homan KJ, Boyatzis CJ (2009) Body image in older adults: links with religion and gender. J Adult Dev 16:230–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9069-8

Beaulieu DA, Best LA (2022) Eat, pray, love: disordered eating in religious and non-religious men and women. J Eat Disord 10:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00721-8

Chaker Z, Chang FM, Hakim-Larson J (2015) Body satisfaction, thin-ideal internalization, and perceived pressure to be thin among Canadian women: the role of acculturation and religiosity. Body Image 14:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.003

Boisvert JA, Harrell WA (2013) The impact of spirituality on eating disorder symptomatology in ethnically diverse Canadian women. Int J Soc Psychiatry 59:729–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764012453816

Boyatzis CJ, Quinlan KB (2008) Women’s body image, disordered eating, and religion: a critical review of the literature. Res Soc Sci Study Relig 19:183–208

Neumark-Sztainer D, Croll J, Story M et al (2002) Ethnic/racial differences in weight-related concerns and behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: findings from Project EAT. J Psychosom Res 53:963–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00486-5

Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Harnack LJ et al (2008) Fruit and vegetable intake correlates during the transition to young adulthood. Am J Prev Med 35:33–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.019

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Eisenberg ME et al (2006) Overweight status and weight control behaviors in adolescents: longitudinal and secular trends from 1999 to 2004. Prev Med (Baltim) 43:52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.014

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J et al (2006) Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: how do dieters fare 5 years later? J Am Diet Assoc 106:559–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003

Pingitore R, Spring B, Garfield D (1997) Gender differences in body satisfaction. Obes Res 5:402–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00662.x

Nangle DW, Johnson WG, Carr-Nangle RE, Engler LB (1994) Binge eating disorder and the proposed DSM-IV criteria: psychometric analysis of the questionnaire of eating and weight patterns. Int J Eat Disord 16:147–157

Johnson WG, Grieve FG, Adams CD, Sandy J (1999) Measuring binge eating in adolescents: adolescent and parent versions of the questionnaire of eating and weight patterns. Int J Eat Disord 26:301–314

Zelitch Yanovski S (1993) Binge eating disorder: current knowledge and future directions. Obes Res 1:306–324

Jackson B, Cooper ML, Mintz L, Albino A (2003) Motivations to eat: Scale development and validation. J Res Pers 37:297–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00574-3

Jeffery RW, French SA, Jeffery W (1999) Preventing weight gain in adults: the pound of prevention study. Am J Public Health 89:747–751

Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, French SA et al (2000) Predictors of weight gain in the pound of prevention study. Int J Obes 24:395–403

Puhl RM, Wall MM, Chen C et al (2017) Experiences of weight teasing in adolescence and weight-related outcomes in adulthood: a 15-year longitudinal study. Prev Med (Baltim) 100:173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.023

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Haines J et al (2007) Why does dieting predict weight gain in adolescents? Findings from Project EAT-II: A 5-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc 107:448–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.013

Christoph MJ, Larson NI, Winkler MR et al (2019) Longitudinal trajectories and prevalence of meeting dietary guidelines during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Am J Clin Nutr 109:656–664. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy333

Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Croll J (2002) Overweight status and eating patterns among adolescents: where do youths stand in comparison with the Healthy People 2010 objectives? Am J Public Health 92:844–851

Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G et al (1994) Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college a national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA 272:1672–1677

Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G et al (1998) Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997 results of the harvard school of public health college alcohol study. J Am Coll Health Assoc 47:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448489809595621

Little RJA (1986) Survey nonresponse adjustments for estimates of means. Int Stat Rev 54:139–157

Kim KHC (2006) Religion, body satisfaction and dieting. Appetite 46:285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.01.006

Homan KJ, Cavanaugh BN (2013) Perceived relationship with God fosters positive body image in college women. J Health Psychol 18:1529–1539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312465911

Jimenez-Morcillo J, Clemente-Suárez VJ (2024) Gender differences in body satisfaction perception: the role of nutritional habits, psychological traits, and physical activity in a strength-training population. Nutrients 16:104. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010104

Hartman-Munick SM, Gordon AR, Guss C (2020) Adolescent body image: influencing factors and the clinician’s role. Curr Opin Pediatr 32:455–460. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000910

Sadatmoosavi Z, Wan Ali WZK, Shokouhi MA (2016) The conceptions of modesty and modest dress in the scriptures of Abrahamic religions. Jurnal Akidah Pemikiran Islam 18:229–270. https://doi.org/10.22452/afkar.vol18no2.6

Kluck AS (2008) Family factors in the development of disordered eating: Integrating dynamic and behavioral explanations. Eat Behav 9:471–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.07.006

Wertheim EH, Martin G, Prior M et al (2002) Parent influences in the transmission of eating and weight related values and behaviors. Eat Disord 10:321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260214507

López-Guimerà G, Levine MP, Sánchez-Carracedo D, Fauquet J (2010) Influence of mass media on body image and eating disordered attitudes and behaviors in females: a review of effects and processes. Media Psychol 13:387–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2010.525737

Rose T, Hope MO, Powell TW, Chan V (2021) A very present help: the role of religious support for Black adolescent girls’ mental well-being. J Community Psychol 49:1267–1281. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22595

Rounsefell K, Gibson S, McLean S et al (2020) Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: a mixed methods systematic review. Nutr Diet 77:19–40

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Award Numbers: R01HL116892, R35HL139853; PI: Dianne Neumark-Sztainer). The first author’s time was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Award Number: T32DK083250; PIs: Melissa Laska, Nancy Sherwood, Catherine Kotz). The second author’s time was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (T32HL150452; PI: Neumark-Sztainer). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

The presented work had support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Award Numbers: R01HL116892, R35HL139853; PI: Dianne Neumark-Sztainer). The first author’s time was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Award Number: T32DK083250; PIs: Melissa Laska, Nancy Sherwood, Catherine Kotz).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. N.S. was responsible for the conception, design, and implementation of Project EAT-II and IV. All the authors contributed to the present study’s conception and design of the study presented in the manuscript. Data analysis was performed by A. B. with the support of C. B. B. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A. B., and all authors commented on the proposal, analysis, and previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the procedures performed in this study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the ethical guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board for studies involving humans.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baltaci, A., Burnette, C.B., Laska, M.N. et al. Religiosity in adolescence and body satisfaction and disordered eating in adolescence and young adulthood: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from project EAT. Eat Weight Disord 29, 59 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01683-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01683-3