Abstract

Background

Obesity causes many physical and mental illnesses. This study compares mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) versus MB-EAT plus implementation intention model for effectiveness on body mass index (BMI), weight self-efficacy, and physical activity in obese women with BMIs ≤ 25 (n = 52).

Methods

In this randomized clinical trial, the participants were selected by the simple random sampling method and randomly divided into three groups. A 12-session MB-EAT of 150 min per session was performed for experimental group I. The experimental group II received MB-EAT alone for physical activity planning and MB-EAT plus implementation intention; also, both groups were compared to the control group. Data were measured by the scales, a questionnaire, and a checklist, and the P-values are based on the results of the generalized estimating equation (GEE) test. P < 0.001 were considered the significance level.

Results

The MB-EAT and MB-EAT + implementation intention effectiveness on the two experimental groups’ BMI, weight self-efficacy, and physical activity was significantly different from the control group. In the integrated group versus the MB-EAT group, BMI, physical activity, and physical discomfort, were more effective than the weight self-efficacy subscales. Both intervention groups were effective on BMI, weight self-efficacy, and physical activity, but the integrated group's effectiveness was more.

Conclusions

The MB-EAT effectiveness trial is theory-based, reducing weight and the psychological and behavioral consequences of overweight and obese adults. The MB-EAT + the Implementation intention model is to plan regular and daily exercise according to each individual's specific circumstances.

Trial registration: The trial registration number: (IRCT20200919048767N1).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Obesity is a multifaceted health condition that is impacted by a multitude of factors, such as genetic predisposition, environmental influences, behavioral patterns, and socioeconomic factors [1, 2]. The fundamental underlying factor in the development of obesity is an imbalance between the consumption of calories and the expenditure of calories [3]. When individuals consistently consume an excess of calories beyond what they expend through physical activity and metabolic processes, the surplus energy is stored as fat, resulting in weight gain and eventually leading to obesity [4]. The obesity prevalence among the Iranian population over 18 years of age is 21.5% (27.3% for women and 13.7% for men) [5]. Obesity is measured by body mass index (BMI). This index is computed by dividing a person’s weight (in kilograms) by height squared (in meters). The BMIs of 19.5–24.9, 25–29.9, 30–35, 35–40, and above 40 indicate a normal, healthy weight, overweight, obesity, severe obesity, and morbid obesity (associated with very high risk), respectively [6]. Individuals' beliefs about their ability to change health behaviors are influential [7]. Nezami et al.’s study showed that increased eating self-efficacy and increased physical activity in the intervention process lead to diet, increased physical activity, and weight loss [8]. Also, in weight control, self-efficacy works best in coordination with changes in general lifestyle, including physical exercise and the provision of social support [9].

Regular physical activity counteracts the major risk factors for heart disease (high blood pressure, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle) and promotes muscle strength, flexibility, and endurance, as well as self-confidence, self-control, and self-esteem, and helps in regulating weight control and body composition. Evidence indicates that although aerobic exercise can play a role in reducing body fat, weight loss programs centered exclusively around physical activity and nutrition may exhibit restricted long-term efficacy. This underscores the significance of incorporating psychological interventions into such programs, targeting areas such as social support, self-esteem, psychological issues, discrimination, and societal influences. By addressing these multifaceted factors, comprehensive interventions can enhance the effectiveness of weight management strategies and promote sustainable outcomes [10, 11]).

Mindfulness-based awareness training (MB-EAT) covers a wide range of mindfulness meditation techniques, conscious eating practices, and guided practices related to self-awareness and self-acceptance. In MB-EAT, three general goals are pursued, such as increasing awareness of internal and external stimuli/increasing physical activity/increasing nutritional knowledge, and introducing a healthy eating style in all training sessions. These three goals can be categorized into two categories: internal awareness (awareness of external stimuli and physiological signs and symptoms of satiety, hunger, and emotions) and external awareness (increased physical activity and nutrition knowledge) [12, 13].

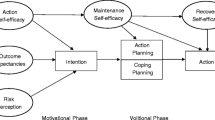

The implementation intention model is an intentional strategy designed to translate intentions into actions and to bridge the gap between intent and behavior [14]. The goal intention is to achieve a goal (i.e., the intention to achieve x), while the implementation intention is related to planning about when, where, and how the intention of the goal becomes behavior (i.e., when faced with y, the intention to start a purposeful behavior x). The important point in implementation intention is when certain environmental conditions are met, it engages the individual in actions that facilitate the conversion of the goal into action [15]. Three processes cause a mismatch between intention and behavior. The first process goes back to the permanence of the intention. This means that most decisions do not arise in the absence of specific abilities, resources, or opportunities; namely, implementation intention occurs when a person has real control over the implementation of behavior [16]. The second process refers to the activation of the intention. Usually, multiple and often conflicting goals at the time activate subsequent goals and behaviors outside the conscious consciousness of individuals [17]. The third process of complexity is intent, meaning that health behaviors can have complex behavioral sequences, with failure to initiate basic behaviors to reduce goal pursuit.

Given the findings, seemingly to lose weight, cognitive changes happen with rising knowledge and awareness and mindfulness practices in the treatment and training sessions, but behavioral changes, such as exercise, require planning, considering environmental conditions, and prioritizing. This activity is a central goal for weight loss because studies have shown that a high percentage of people cite lack of time and busyness as reasons for not exercising [18]. Therefore, due to the growing trend of obesity, this randomized clinical trial study compared the MB-EAT versus MB-EAT plus implementation intention model for effectiveness on BMI, weight self-efficacy, and physical activity in obese women with BMIs ≤ 25 (n = 52).

Literature review

Hatar et al. in a study showed that the intentional behavior program causes primary outcomes, including weight loss, and secondary outcomes, including a decrease in BMI, body fat percentage, muscle mass, waist-pelvic ratio, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, lipoprotein, cholesterol, triglycerides, blood sugar, and insulin levels, and psychological changes, including improving quality of life, motivation, risk perception, life expectancy, Intention to change, functional self-efficacy, maintenance self-efficacy, goal self-regulation, planning self-regulation and behavioral self-regulation, including self-reported dietary intake and involvement in physical activity [19].

Methods

Statistical population, sample, and sampling method

This applied study was a clinical trial (The trial registration number: IRCT20200919048767N1) with a control group (waiting list). In the present study, among the statistical population of 75 overweight and obese women with a BMI equal to or higher than 25, referred to the internal and subspecialty endocrinology clinic of Shahid Bahonar Karaj Hospital in 2019, using a simple random sampling method, 61 people were selected by referring to Krejci-Morgan’s table.

Through virtual networks, they were invited to participate in the study for two months in the winter of 2019.

After selecting the statistical sample and the screening process based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the participants were randomly divided into three groups: two experimental groups and one control group. The groups were homogenized in terms of weight, waist circumference, and age. In this study, inclusion criteria for entering the study included a BMI of 25 or more, an age of 20 years and above, having a high school diploma or higher, and signing the written informed consent form by the patients to participate in the study. Receiving psychotherapy or other programs of weight loss and regular exercise simultaneously, use of psychotropic or weight-affecting drugs, hypothyroidism, pregnancy, and diabetes diagnosed under the supervision of an endocrinologist were considered exclusion criteria. The consort flow diagram of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Research ethics approval

The project was found to be following the ethical principles and the national norms and standards for conducting Medical Research in Iran and it was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Islamic Azad University—Karaj Branch (Approval ID: IR.IAU.K.REC.1399.028). The study was conducted according to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Date of approval of the plan in the scientific committee

Date of approval of the plan in the scientific committee/council: 11/11/2019.

Project number in the university system (student number): “950520000”.

Instrument measurements

-

A)

Evaluation of biomarkers: Digital scales for weight measurement and BMI are calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height squared in meters [20].

-

B)

Demographic and nutritional information: Questions to measure demographic information about age, marital status, education, and occupation were set by the self-reporting method. Basic information on the amount, type, and timing of feeding was recorded on two working days and one day off, and in the intervention and follow-up process, it was in the form of a daily report and a checklist. Physical activity in the form of reporting and marking on a researcher-made checklist on a Likert scale (with a score range of 1–7 per week), including 30 min of brisk walking, was measured by statements such as “I have at least 30 min of brisk walking a day.” By assessing the content validity, the scientific validity of the tools was assessed, and corrective comments were applied to it. A day off was recorded, and in the process of intervention and follow-up, it was in the form of a daily report and a checklist. To check the content validity, Content Validity Ratio (CVR), Content Validity Index (CVI) indexes, and the opinion of five teachers in the health psychology field and faculty members of the university were used. For all items, the number 0.6 was obtained.

-

C)

The Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire: It was developed by Clark et al. and consists of 20 items of five subscales that increase the likelihood of eating behavior [21, 22]. These subscales include negative emotions, access to food, social pressures, physical discomfort, and eating as positive and fun activities. Therefore, it provides an overall score and five subscales assessing from uncertainty = 0 to very confident = 5 on a 5-point Likert scale.

-

D)

The MB-EAT: It includes insight and awareness of internal and external symptoms in which the person with mindful eating, learns the difference between physical hunger and eating stimuli-based hunger, the process of satiety and normal satiety, mindful calorie-counting, and practices attention to internal symptoms in eating instead of external stimuli [23].

Research procedure (randomization)

After selecting 61 people (n = 61) purposefully and reviewing the inclusion and exclusion criteria, using the demographic information tool, BMI was measured with the required tools. The amount of energy intake, type of nutrition, eating hours, and physical activity, were recorded by the subjects with prior notice in two working days and one day off and were reported to the researcher. The study participants were enrolled through random assignment and were matched for weight and age indices to ensure homogeneity. The group members were subsequently assigned to three groups through a process of simple randomization, which involved using random number tables to determine group allocation by chance. Envelopes containing the assigned interventions were used to allocate participants into three groups: experimental I (n1 = 20), experimental II (n2 = 21), and control (n3 = 20). The therapist and physician administered the questionnaires and collected weight data from all three groups, while also recording basic information. The group members were then randomly assigned to their respective groups. Due to the interactive nature of the interventions and the therapist-patient interaction required, blinding both the participants and the therapists providing the interventions was not feasible in this study. The group I received MB-EAT training in 12 sessions, one session per week for 150 min in person. After four sessions due to the Covid-19 disease pandemic and the start of quarantine, the sessions continued online via Skype. To prevent the effect of the condition on the performance of the participating members, additional exercises were given at the beginning of the epidemic. In each session, members of the group I were asked to practice the techniques and meditations learned daily at home, review the exercises learned with one of their group members once a week, and report on their experiences.

For group II, as in group I, MB-EAT training was performed simultaneously with the same duration and number of sessions and with the same circumstances in presenting content and techniques according to the protocol; also, at the end of each session, like the group I, the members of group II were asked to perform techniques and meditations learned in each session every day at home and a weekly session with one of their group mates to review exercises and reporting the obtained experiences. In setting the plan, the persistence of the intention, i.e., the actual control over the performance of the work that is commensurate with the individual's ability, activating the intention, i.e., removing obstacles and competing behaviors and overcoming the complexities of the intention, which could allow the implementation intention, were considered [16]. Participants in group II recorded physical activity every day and reported it to the researcher in the virtual group for a specified period; for example: If I want to lose weight, then I have to walk 30 min a day before going to work. For group II, the conditions for continuing training sessions, such as experimental group I, continued online after four face-to-face sessions. For the control group, a virtual group was formed to coordinate the measurement of variables and information to start the course. After completing the training of the two groups and collecting data after follow-up, MB-EAT training was conducted online for this group. While collecting data, three participants in group I and two participants in group II were unable to continue their sessions due to a lack of internet access or problems installing Skype. Also, the data of four people in the control group were deleted because they did not fill in the questionnaires in three rounds.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics for the quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were employed to compare the effects of the MB-EAT and MB-EAT + Implementation Intention groups with the control group on physical activity, BMI, and weight self-efficacy components throughout the study period (baseline, month 1, and month 2). A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was conducted using the SPSS.

Results

The age’s mean and standard deviation in the I, II, and control groups were 40.58 ± 8.34, and 37.84 ± 8. 52, and 39.50 ± 7.41, respectively. The height’s mean and standard deviation in the I, II, and control groups were 161.84 ± 5.35, 157.41 ± 6.27, and 163.12 ± 5.43, respectively. Also, the weight’s mean and standard deviation in the I, II, and control groups were 76.82 1 1.13, 77.00 ± 1.07, and 77.00 ± 0.96, respectively.

The results of the P-values are based on the results of generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis to explain the main effects of independent variables on physical activity, body mass index, and weight self-efficacy components are shown in Table 1.

Physical activity

The results in the above table indicated that at baseline, the MB-EAT and MB-EAT + Implementation groups had a higher physical activity compared to the control group and there is no significant difference between them at baseline (respectively, P = 0.673 and P = 0.691). Table 1 and Fig. 2 showed that physical activity significantly increased in the first follow-up compared to the baseline (\(\upbeta\) = 0.31, P = 0.007). This variable also increased in the second follow-up compared to the baseline, and this was a significant increase (\(\upbeta\) = 0.12, P = 0.404). In addition, there is a significant difference between the physical activity of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups (P < 0.001) in the first follow-up measurement. In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the physical activity of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is more than observed in the first follow-up measurement. There is a significant difference between the physical activity of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups in the first follow-up measurement (P = 0.010). In the second follow-up measurement, there is no significant difference between the physical activity of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P = 0.071) and this difference is less than observed in the first follow-up measurement.

BMI

There is a significant difference between the BMI of the MB-EAT and control groups in the first follow-up measurement (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the BMI of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is more than observed in the first follow-up measurement. In addition, there is a significant difference between the BMI of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups (P < 0.001) in the first follow-up measurement. There is a significant difference between the BMI of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups in the second follow-up measurement (P < 0.001) and this difference is more than observed in the first follow-up measurement. In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the BMI of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P = 0.001). There is a significant difference between the BMI of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups in the second follow-up measurement (P = 0.001) and this difference is less than observed in the first follow-up measurement.

Negative emotions

In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the negative emotions of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between negative emotions of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. Besides, there is a significant difference between the negative emotions of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups in the first follow-up measurement (P < 0.001). There is a significant difference between negative emotions of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups in the second follow-up measurement (P < 0.001) and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. In the first follow-up measurement, there is no significant difference between negative emotions of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P = 0.674). Also, in the second follow-up measurement, there is no significant difference between negative emotions of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P = 0.514).

Food access

In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between food access of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between food access of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is less than observed in the first follow-up measurement. In addition, in the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between food access of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups (P < 0.001). There is a significant difference between food access of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups in the second follow-up measurement (P < 0.001). There is no significant difference between food access of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups in the first and second follow-up measurements (respectively, P = 0.476, P = 0.412).

Social pressure

Table 1 and Fig. 2 showed that social pressure increased in the first follow-up compared to the baseline (β = 0.06, P = 0.704). This variable also decreased in the second follow-up compared to the baseline, and this was a significant decrease (β = − 0.44, P = 0.043). In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the social pressure of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the social pressure of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001), and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. Besides, there is a significant difference between the social pressure of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups in the first follow-up measurement (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the social pressure of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. There is no significant difference between the social pressure of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups in the first follow-up measurement (P = 0.623). In the second follow-up measurement, there is no significant difference between the social pressure of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P = 0.274).

Physical discomforts

Table 1 and Fig. 2 showed that physical disco decreased significantly in the first follow-up compared to the baseline (β = − 0.38, P = 0.002). This variable also decreased in the second follow-up compared to the baseline, and this was a significant decrease (β = − 0.62, P = 0.001). In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the physical discomfort of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the physical discomforts of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. Besides, there is a significant difference between the physical discomforts of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups in the first follow-up measurement (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the physical discomforts of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the physical discomforts of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P < 0.001). There is a significant difference between the physical discomforts of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups in the second follow-up measurement (P < 0.001) and this difference is larger than observed in the first follow-up measurement.

Fun eating

The results in the above table also indicated that in baseline the MB-EAT and MB-EAT + Implementation groups had higher fun eating compared to the control group and there was no significant difference between them in baseline (respectively, P = 0.091 and P = 0.979). Table 1 and Fig. 1, showed that fun eating increased in the first follow-up compared to the baseline (β = 0.12, P = 0.131). This variable also increased in the second follow-up compared to the baseline and this was a significant increase (β = 0.25, P = 0.021). In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the fun eating of the MB-EAT and control groups (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the fun eating of the MB-EAT and control groups (p < 0.001) and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. In addition, there is a significant difference between fun eating of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups in the first follow-up measurement (P < 0.001). In the second follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between fun eating of the MB-EAT + Implementation and control groups (P < 0.001) and this difference is higher than observed in the first follow-up measurement. In the first follow-up measurement, there is a significant difference between the fun eating of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P = 0.036). In the second follow-up measurement, there is no significant difference between the fun eating of the MB-EAT + Implementation and MB-EAT groups (P = 0.064) and this difference is less than observed in the first follow-up measurement.

Figure 2 shows the changes in the studied dependent variables’ components in the experimental groups.

Discussion

As shown by the results of statistical analysis, a significant difference existed between the groups receiving MB-EAT and MB-EAT + Implementation with the control group in BMI, weight self-efficacy, and physical activity. Also, a significant difference existed between greater effectiveness in BMI, negative emotion components, and physical discomfort in weight self-efficacy and physical activity in the group receiving MB-EAT + Implementation and the group receiving only MB-EAT. In the BMI index, this study is consistent with Sarto et al.’s study, and Daubenmier et al.’s study [17, 24, 25]; also, as the positive correlation between mindfulness and inhibited eating, which results from an increase in weight self-efficacy, this study is consistent with the study conducted by Ouwens et al. [26]; in physical activity, and with the studies of Kristeller et al. [13], Jordan et al. [27], Burton and Smith [28], and Köse and Çıplak [29]. To date, no intervention has been performed for MB-EAT + implementation intention, but the integration of implementation intention with mental imagery is consistent with the study of Hattar et al. [19]; also, in terms of changing unwanted and addictive behaviors, it is consistent with the studies conducted by Adriaanse et al. [30], Adriaanse et al. [31], and Sullivan and Rothman [32]; and in weight loss, weight self-efficacy, and physical activity, it is consistent with the study conducted by Hattar et al. [19].

One potential point of discussion is the underlying mechanisms by which mindfulness-based interventions can facilitate improvements in weight management and overall well-being. Mindfulness practices have demonstrated the ability to enhance self-awareness and reduce impulsive eating behaviors, potentially leading to weight loss. Furthermore, practicing mindfulness can assist individuals in cultivating a more positive body image and fostering a healthier relationship with their bodies, resulting in increased motivation to engage in physical activity.

Another noteworthy aspect to consider is the role of implementation intentions in promoting behavior change. Implementation intentions involve creating specific plans outlining when, where, and how a behavior will be performed. In the present study, participants who received MB-EAT in conjunction with implementation intentions were able to develop personalized plans for regular and daily exercise, tailored to their circumstances. This personalized approach may have contributed to their greater success in increasing physical activity compared to the group that solely received MB-EAT.

It would be valuable to discuss the implications of these findings for healthcare professionals who work with individuals affected by obesity. The results suggest that the inclusion of mindfulness-based interventions in weight management programs can have positive impacts on both physical and mental health outcomes. Moreover, integrating implementation intentions into these interventions may enhance their effectiveness by providing individuals with practical strategies for incorporating healthy behaviors into their daily lives.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the study. The sample size was relatively small (n = 52), which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study only included obese women with BMIs ≤ 25, thus limiting the applicability of the results to other populations. Future research could explore the effectiveness of these interventions in larger and more diverse samples to further validate the findings.

Conclusions

The results showed that MB-EAT and MB-EAT + Implementation intention are effective in reducing BMI, increasing self-efficacy, and increasing physical activity. However, in comparison with the two groups, the effectiveness of the integrated group on reducing BMI, increasing physical activity, and reducing physical discomfort and negative emotions was greater than the weighted self-efficacy subscales, but in the subscales of food access, social pressures, and eating, no significant difference was observed between the two groups. Although it was feared that quarantine restrictions from the COVID-19 epidemic would affect outcomes, through increased awareness and cognitive flexibility in emotion management, awareness of external and internal stimuli, and awareness of healthy eating styles, all of which are important for changing a person's relationship with food, MB-EAT appears to facilitate weight loss and stability of the decreased weight.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- MB-EAT :

-

Mindfulness-based eating awareness training

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CVR:

-

Content validity ratio

- CVI:

-

Content validity index

References

Cohen R, Shikora S (2020) Fighting weight bias and obesity stigma: a call for action. Obes Surg 30(5):1623–1624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04525-0

Kadouh HC, Acosta A (2017) Current paradigms in the etiology of obesity. Tech Gastrointest Endosc 19(1):2–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tgie.2016.12.001

Fock KM, Khoo J (2013) Diet and exercise in management of obesity and overweight. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28:59–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12407

Manore MM, Larson-Meyer DE, Lindsay AR, Hongu N, Houtkooper L (2017) Dynamic energy balance: an integrated framework for discussing diet and physical activity in obesity prevention—is it more than eating less and exercising more? Nutrients 9(8):905. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080905

Agah Heris M, Alipour A, Janbozorgi M, Mousavi E, Noohi S (2012) A comparative study of effectiveness on life-style modification and cognitive group therapy to weight management and quality of life enhancement. Q J Health Psychol 1(1):68–80

Folsom AR, Kaye SA, Sellers TA, Hong C-P, Cerhan JR, Potter JD et al (1993) Body fat distribution and 5-year risk of death in older women. JAMA 269(4):483–487. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1993.03500040049035

Dutton GR, Martin PD, Rhode PC, Brantley PJ (2004) Use of the weight efficacy lifestyle questionnaire with African American women: validation and extension of previous findings. Eat Behav 5(4):375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.005

Nezami BT, Lang W, Jakicic JM, Davis KK, Polzien K, Rickman AD et al (2016) The effect of self-efficacy on behavior and weight in a behavioral weight-loss intervention. Health Psychol 35(7):714. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000378

Van Duyn MAS, Kristal AR, Dodd K, Campbell MK, Subar AF, Stables G et al (2001) Association of awareness, intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, and stage of dietary change with fruit and vegetable consumption: a national survey. Am J Health Promot 16(2):69–78. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-16.2.69

Consultation W (2000) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 894:1–253

Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, Lew A-M, Samuels B, Chatman J (2007) Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol 62(3):220. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220

Kristeller JL, Baer RA, Quillian-Wolever R (2006) Mindfulness-based approaches to eating disorders. In: Baer RA (ed) Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications. Elsevier, Amsterdam, p 75

Kristeller J, Wolever RQ, Sheets V (2014) Mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) for binge eating: a randomized clinical trial. Mindfulness 5(3):282–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0179-1

Webb TL, Sheeran P (2006) Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull 132(2):249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249

Gollwitzer PM (1993) Goal achievement: the role of intentions. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 4(1):141–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000059

Ajzen I (2020) The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2(4):314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

Aarts H, Gollwitzer PM, Hassin RR (2004) Goal contagion: perceiving is for pursuing. J Pers Soc Psychol 87(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.1.23

Milne S, Orbell S, Sheeran P (2002) Combining motivational and volitional interventions to promote exercise participation: protection motivation theory and implementation intentions. Br J Health Psychol 7(2):163–184. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910702169420

Hattar A, Hagger MS, Pal S (2015) Weight-loss intervention using implementation intentions and mental imagery: a randomized control trial study protocol. BMC Public Health 15(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1578-8

Fruh SM (2017) Obesity: risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long-term weight management. J Am Assoc Nurs Pract 29(S1):S3–S14. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12510

Clark MM, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Eaton CA, Rossi JS (1991) Self-efficacy in weight management. J Consult Clin Psychol 59(5):739. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.5.739

Ahmadi E, Kazemi SA (2021) The relationship between weight efficacy life style dimensions and perceived parental styles dimensions with psychological well-being in students. J Res Health 11(2):123–130. https://doi.org/10.32598/JRH.11.2.1639.2

Kristeller JL, Jordan KD (2018) Mindful eating: connecting with the wise self, the spiritual self. Front Psychol 9:1271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01271

Sarto HM, Barcelo-Soler A, Herrera-Mercadal P, Pantilie B, Navarro-Gil M, Garcia-Campayo J et al (2019) Efficacy of a mindful-eating programme to reduce emotional eating in patients suffering from overweight or obesity in primary care settings: a cluster-randomised trial protocol. BMJ Open 9(11):e031327. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031327

Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, Maninger N, Kuwata M, Jhaveri K et al (2011) Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: an exploratory randomized controlled study. J Obes. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/651936

Ouwens M, Schiffer A, Visser L, Raeijmaekers N, Nyklíček I (2015) Mindfulness and eating behaviour styles in morbidly obese males and females. Appetite 87:62–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.030

Jordan CH, Wang W, Donatoni L, Meier BP (2014) Mindful eating: Trait and state mindfulness predict healthier eating behavior. Pers Individ Differ 68:107–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.013

Burton ET, Smith WA (2020) Mindful eating and active living: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary pediatric weight management intervention. Nutrients 12(5):1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051425

Köse G, Çıplak E (2020) Mindful eating questionnaired: eating control, emotional eating and conscious nutrition trio. Prog Nutr. https://doi.org/10.23751/pn.v22i2.9312

Adriaanse MA, Vinkers CD, De Ridder DT, Hox JJ, De Wit JB (2011) Do implementation intentions help to eat a healthy diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Appetite 56(1):183–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.10.012

Adriaanse MA, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM, Hennes EP, De Ridder DT, De Wit JB (2010) When planning is not enough: fighting unhealthy snacking habits by mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII). Eur J Soc Psychol 40(7):1277–1293. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.730

Sullivan HW, Rothman AJ (2008) When planning is needed: implementation intentions and attainment of approach versus avoidance health goals. Health Psychol 27(4):438. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.438

Acknowledgements

This article is taken from the Ph.D. dissertation of Ms. Mona Jassemi Zergani in Health Psychology, Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, Faculty of medical sciences, Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch in 2020. The authors of this article would like to thank Professor Jane Kristeller, the creator, and Andrea Lieberstein, the instructor, for providing the MB-EAT course for one of the authors of this article (Mona Jassemi Zergani). We also thank the esteemed teachers and participants in the research for their cooperation.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mona Jassemi Zergani (M.J.Z) Mohammad Hossin Taghdisi (MH.T); Mohammadreza Seirafi (M.S); Saied Malihialzackerini (M.A); Habibeh Taghavi Kojidi (H.T.K). M.J.Z participated in the MB-EAT course and implemented MB-EAT sessions for participants. M.J.Z, M.T, M.S, M.A, and H.T.K extracted, analyzed, and interpreted the questionnaires’ data. M.J.Z and M.S were major contributors to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is part of the results of the doctoral dissertation on health psychology at the Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch, which was reviewed and approved by the university ethics committee and the specific ID of the ethics committee (IR. IAU. K. REC. 1399.028) and has the code (IRCT20200919048767N1) in the trial registration. Participants signed the written informed consent form by the patients to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that “they have no competing interests” in this section.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zergani, M.J., Taghdisi, M.H., Seirafi, M. et al. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training versus itself plus implementation intention model: a randomized clinical trial. Eat Weight Disord 29, 53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01677-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01677-1