Abstract

Background

Although studies have traced the impact of COVID-19 on those with eating disorders, little is known about the specific impact of the pandemic on Black American women who report disordered eating behaviors and are at risk for eating disorders. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on Black women who binge-eat.

Methods

We recruited a purposive sample during the first wave of COVID-19 from the southeastern United States. Participants identified as Black women, reported binge-eating episodes in the last 28 days, and agreed to participate in a semi-structured interview. Prior to the interview, participants were administered a socio-demographic survey and the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed independently using qualitative content analysis and open coding to identify relevant codes and themes.

Results

On average, participants (N = 20) were 43.05 ± 16.2 years of age and reported 5.6 ± 5.7 binge-eating episodes in the last 28 days. We identified six themes to describe participants' experiences managing their eating behavior during COVID-19: (1) food as a coping strategy; (2) lack of control around food; (3) increased time in a triggering environment (e.g., being at home with an easy availability of food); (4) lack of structure and routine; (5) challenges with limited food availability; and (6) positive impact of the pandemic.

Conclusion

In this study, Black women reported challenges managing their eating behavior during COVID-19. Results could inform the development and tailoring of treatments for Black women reporting disordered eating behaviors.

Level of Evidence

Level V, qualitative interviews.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has had far-reaching, significant impact on mental health, physical activity, and eating behaviors all over the globe, it has been particularly challenging for Black Americans. For example, in 2020, Black Americans had three times the risk of White Americans to become ill from COVID-19 [1]. Moreover, according to COVID-19 mortality rates captured though July 2020, nearly 98 out of every 100,000 Black Americans had died from COVID-19, a mortality rate that was more than double that for Whites (46.6 per 100,000) and Asians (40.4 per 100,000) [1,2,3]. Recent data from February 2022 show that disparities persisted, with Black Americans continuing to have significantly higher rates of COVID-19 infection and death as compared to White Americans [4]. Further, Black Americans are over-represented in essential service industry positions, work that is often low-wage, may lack adequate health benefits, and may increase exposure to COVID-19 as they have no option to work from home [3]. These experiences highlight the greater personal, social, and financial stress as brought on by the pandemic; for example, a recent study detailed how Black women reported their employment was negatively affected by the pandemic, had more worries about how the pandemic would impact their finances, and reported higher anxiety and depression than their White counterparts [5]. In sum, during COVID-19, Black Americans have faced specific and complex challenges that could adversely affect their psychosocial functioning.

As part of investigating COVID-19’s unique and often disproportionate effects on Black Americans, it is essential to understand the secondary challenges faced by Black Americans with eating disorders (EDs). It has been reported that individuals with EDs are experiencing changes in treatment options (i.e., either limited or converted to telehealth platforms), a worsening of symptoms, and heightened concerns about shape and weight due to the pandemic’s limitation of their access to regular physical activity [6, 7]. Certainly, changes in the availability of treatment, isolation due to social distancing, and financial barriers may further interfere with treatment progress and contribute to potential relapse in those with disordered eating behaviors [7, 8].

These changes to treatment may present even worse consequences for Black Americans who are managing eating disorders. Prior to the pandemic, Black Americans were less likely to access treatment for eating disorders and, when enrolled, were more likely to drop out compared to their White counterparts [9]. Various reasons for this disparity have been documented, including cost of treatment, shame, lack of insurance, and limited availability of treatment providers who are also Black [10]. Currently, research is extremely limited in identifying the needs of Black patients with disordered eating behaviors and EDs [9, 10].

Understanding and examining the current needs of Black patients with disordered eating and who are at risk for EDs will offer critical guidance to clinicians about how to deliver the most effective and relevant services to this vulnerable population in the context of COVID-19. To date, almost no studies of COVID-19’s impact on individuals with eating disorders have focused specifically on Black individuals. Due to the differential effects of COVID-19 on this population, findings will help clinicians and policymakers understand and customize treatments to meet their needs. To this end, the purpose of the current study was to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black women reporting binge-eating and who were at risk for binge-eating disorder using a fundamental qualitative research design.

Methods

Positionality statement

We begin this work by describing the perspective from which we undertook this study. The first and third author identify as a Black American cisgender women and have expertise in the study of eating behaviors among Black American women. Due to their personal identification with the race and ethnic identity of many of the participants, intentional effort was made to bracket any existing biases or assumptions that may affect the analyses. The second and fourth author identify as White American cisgender women and are both graduate students. The fifth and sixth author both identify as Black American cisgender women, with one currently in a doctoral program, and the other completing her undergraduate education. The seventh author identifies as a Latina cisgender female and was an undergraduate student at the time of data collection. Finally, the eighth author identifies as a White cisgender female with expertise in conducting research on the biological and genetics of eating disorders. All authors worked collectively to interpret the findings, both to ensure that the findings were culturally sensitive and to ensure that our interpretations faithfully reflected the phenomenon as represented by the data.

Qualitative methodology

Our phenomenon of interest was the impact of COVID-19 on the eating behaviors of Black women with self-reported disordered eating. Given the continued disparities in screenings for and treatment of eating disorders among Black Americans [6, 11, 12], it was important to choose a qualitative methodology that would enhance our ability to assess, develop, and refine clinical interventions to treat disordered eating in this population [7]. For this reason, we chose a fundamental qualitative description design [13, 14]. This design is typically employed when investigators want to generate an interpretation that is low-inference, or that will make sense to a large swath of researchers. In this design, results are typically presented in plain, everyday language to provide straightforward answers to clinicians and policymakers [14]. A widely accessible presentation of the results is critical to facilitating their uptake and in turn improving treatment options for Black Americans experiencing eating disorders.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (mid-March 2020). Our research team sent emails to previous participants in a recent pilot study to treat binge-eating in this population, asking these participants to participate in the present study. We also sent an announcement via a university listserv to recruit individuals who report feeling out of control around food to an interview about their eating and weight concerns. Additionally, we used snowball sampling and asked previous research participants to identify potential participants from individuals in their networks. To be eligible for the study, participants had to: (1) identify as a Black/African American woman; (2) be between 18 and 75 years of age; (3) report at least one episode of loss of control while eating in the last 28 days; and (4) meet BMI criteria for overweight or obesity. The rationale for this inclusion criterion was to recruit women who have recurrent episodes of binge-eating, and who may be at risk for binge-eating disorder. Additionally, the present study is part of a larger study with the aim to investigate the factors affecting the eating behaviors of Black women who binge-eat and who experience concurrent obesity.

Data collection

The Institutional Review Board at a large southeastern university approved this study. Data were collected using individual, semi-structured interviews via Zoom in March and April of 2020. Interviews were conducted by two research team members, both of whom identify as African American women. All interviews were recorded and lasted between 45 and 90 min. Participants were compensated with a $35 VISA gift card. After obtaining informed consent, individuals were asked to complete two surveys: a socio-demographic survey, and the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire [15]. Our semi-structured interview guide Table 1 included open-ended questions developed to elicit participants' perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on their eating behaviors. Each participant was asked to respond to several questions assessing their normal eating patterns, factors affecting the beginning and ending of binge-eating episodes, the impact of COVID-19 on their eating behaviors, and factors affecting their experience of binge-eating episodes.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim using computer-assisted technology. We then began a process to uncover meaning and formulate common themes across the participants' transcripts. To ensure the rigor of the data analysis process, transcripts were hand-coded by members of the research team. We used in vivo coding to represent the language as used by the participants and a team of coders (HM, DC, TN, LB, MT) identified these significant words and phrases pertaining directly to the lived experience of making eating decisions during COVID-19. Initial codes were reviewed by three team members, and then refinements to the list of codes were made through two additional rounds. Similar codes were grouped together to uncover our initial themes. To establish intercoder agreement, members of the coding team were each assigned the same section of transcripts to review. Any disagreements in coding were adjudicated by a joint discussion, with the final decision and/or any tie breaking by the first author, who also served as the PI for this study. Results were integrated and preliminary themes were developed to capture and describe the phenomenon.

Results

A purposive sample of 20 Black women who reported binge-eating behaviors participated in this study. Table 2 reports the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. On average, participants were 43.1 ± 16.2 years of age, had a BMI of 36.8 ± 5.9, and reported 5.6 ± 5.7 objective binge-eating episodes in the last 28 days, as measured by the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire.

Impact of COVID-19 on Black women reporting binge-eating framework

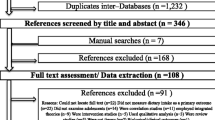

The rich and illustrative descriptions provided by the participants formed the basis for the framework that describes the experience of COVID-19 for Black women reporting binge-eating. The Impact of COVID-19 on Black Women framework presents the behavioral and psychological changes experienced by Black women reporting binge-eating during the first wave of COVID-19 (see Fig. 1). The framework highlights the role of five different themes that describe participant experiences managing their eating behavior during COVID-19: (1) using food as a coping mechanism; (2) experiencing a lack of control around food; (3) spending increased time in a triggering environment (e.g., being at home with food easily available); (4) lack of structure and routine; and (5) limited food availability (e.g., COVID-19-related disruptions to food availability led participants to buy shelf-stable foods that they typically avoided). We also highlight the positive changes in food habits participants observed due to COVID-19. All these themes co-exist within the context of the participants’ intersectional identities of race/ethnicity, class, and gender, and COVID-19 fear and contagion. Below we further describe these themes and offer illustrative quotes from participants.

Food as a coping strategy

Participants described their experiences of eating to cope with their emotions, boredom, and the situation they were in due to COVID-19. For many, having to quarantine and being alone contributed to their desire to eat more than normal and to use of food as a tool for comfort and survival during the early days of the pandemic, a period when the factors affecting the spread of COVID-19 were unknown. Further, being in quarantine may have triggered feelings of loneliness and boredom. Several noted the presence of boredom eating, noting that it was “something to look forward to” on a regular basis. Others noted an increase in stress levels that may have contributed to an increase in overeating, citing it as a way of coping that provided comfort during this difficult time. One participant explained her scenario in this manner:

“And honestly still goes back to probably boredom. Cause I'm sitting still more, I'm looking at more TV than I ever had. I'm catching up on…I'm binge watching like all these TV shows people have talked about probably for years…I'm sitting still. So, what do you do when you're sitting still? And you're looking at TV. I don't knit. I don't crochet. I don't, you know what else has made it for me to do? Eat.”

Increase in lack of control around food

A common theme observed among participant responses was experiencing a great loss of control in their eating behaviors. Participants stated that because they were at home more often, the availability of food and their access to it increased, potentially influencing their ability to control their eating habits and decrease their satiety. For example, one participant explained that because lunch, dinner, and snacking all blended together, they found there was not a true stopping point to their eating. Another participant described being aware that they were overeating and watching it happen but were unsure how to stop. For example, one participant noted that “Since COVID, I have wanted to eat the whole dessert. Since COVID, I'm not satisfied with anything and God it feels like I'm never done.”

Additionally, participants reported noticing sensations of fullness but continuing to eat anyway. This was described as feeling stuffed or “the full that you know you shouldn’t get to.” Overall, participants noted that the lack of control experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic affected their sense of loss of control around food and their response to their body’s signals of satiation.

Increased eating due to staying at home

Participants noted that being confined to their homes became a significant trigger for increased eating. Participants shared that their homes were often environments with large amounts of food readily available. In fact, several participants found themselves making more trips to the kitchen and the refrigerator throughout the day because it was easily accessible. As one participant described, “I'll be honest, even with the coronavirus and working from home and the fridge being there, it was, it's also been kind of a procrastination technique… I may have like 15 trips to the fridge back and forth.”

Participants discussed several reasons for this increased consumption, including stockpiled food due to uncertainty over food availability and increased time at home. Several participants reported consuming food that was meant to last throughout the unpredictability of the pandemic “just because it was there.” Other participants described eating more food simply because they were home more. Overall, being at home and having constant access to food led to challenges in managing food intake among participants.

Lack of structure and routine

Ten participants expressed ways in which the pandemic and stay-at-home orders resulted in a lack of structure or routine in their lives, and in turn influenced them in many ways, including increased or decreased exercising, eating out of boredom, staying up too late, and mindlessly snacking. Additionally, one participant described that working from home interrupted their pre-pandemic routine, leading them to ignore their hunger cues and wait until they were ravenous to eat, which then led them to overeating. Overall, it appeared that a disruption in routine contributed to increased challenges navigating their eating behaviors. One participant described how their routine has changed since the pandemic, noting, “I definitely have been staying up later and then eating at night. And so normally I would probably like if it was a regular workday, I would probably be in bed…and I wouldn't be eating anything, but now I don't know. I don't have a real bedtime. So, then I'll probably eat something.”

Limited food availability

Nine participants described the impact of national measures aimed at reducing and controlling COVID-19 infection rates and the associated challenges with disruptions in food availability and accessibility. Often, participants purchased foods they would not normally eat and/or foods that were either less expensive or non-perishable because they knew they were going to have to be homebound for several weeks. One participant described their experience in this manner:

“So, I purchased abunch of like non-perishable things, like canned tuna, rice and beans, potatoes, stuff …that I could have if I needed to be in the house for four to six weeks…the first two weeks of, um, staying at home, we legit stayed at home. Like we didn't go anywhere, not even to a grocery store and, uh, was just eating all of those foods that I normally wouldn't eat because that's what we had accessible. Um, and so then we were eating like peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, which, nothing wrong with that, but that's not something I normally eat like hardly ever. I found myself for those two weeks just kind of eating stuff like that because I thought I could not go anywhere.”

Additionally, the limited availability of food influenced participants to buy more refined foods, heavily processed foods, or foods higher in fat or sugar. Overall, the limited availability of food in grocery stores led to participants stocking up at home with foods they would not usually eat, which increased challenges associated with managing eating behaviors.

Positive impact of COVID-19 on food choices

Though negative effects of the pandemic on eating behaviors were more common, some participants (n = 8) also described positive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their eating behaviors. With the additional time at home, some participants reported they were able to cook more and make healthier choices. Several participants noted that having to be at home made them more mindful of what they were eating and how much, but not in an excessive way. As one participant noted: “I have to cook my own meals and I try to be a little bit more mindful about what I buy, what type of meals that I make for myself.”

Participants also reported positive aspects of social isolation and quarantine. Several participants explained how they were able to continue being physically active at home through going outside more or using workout equipment in their house. Being at home also helped some participants feel free from judgment regarding exercise or changes in their diets. Furthermore, while participants reported that they were not able to interact with others as much, they were still able to prioritize seeing loved ones (via video chat or in a socially distanced way) and became more comfortable being alone.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine the impact of COVID-19 on Black women reporting binge-eating and who were at-risk for binge-eating disorder. Similar to previous studies reporting the negative effects of COVID-19 on eating behaviors more broadly [6,7,8], our data showed that in our sample of Black women participants, there were recurrent challenges in navigating eating and food use related to COVID-19. Participants thoughtfully spoke about their challenges managing episodes when they lost control of eating and using food as a coping tool or emotion regulation strategy. Furthermore, participants noted the increased difficulty of having extended time at home where food was often plentiful, having limited access to structure and routine, and spending increased time in a triggering environment. Though many of our participants described the negative challenges of the pandemic, several also noted “silver linings,” including but not limited to being able to cook more and increased physical activity. Indeed, participants noted that the impact of COVID-19 was complex and multi-layered, prompting further reflection on the role of food during times of distress.

Most participants reported an increase in lack of control during eating episodes since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may explain the number of binge-eating episodes observed in this sample. Several factors likely influenced the experience of loss of control behaviors, including increased stress, changes in routines, and increased pandemic-related anxiety. Our results corroborate previously documented increases in loss of control eating during the COVID-19 lockdown [16,17,18]. For example, one study of 129 individuals experiencing or recovering from an eating disorder reported decreased feelings of control around food [24]. Furthermore, in a cross-sectional study with 254 adults after the first mandatory COVID-19 lockdown, 47% of participants noted a loss of control around eating [28]. Clearly, perceived control surrounding eating behaviors have been exacerbated in recent years by a combination of pandemic-related factors.

Just as many populations worldwide have reported an increase in disordered eating behaviors as a response to the uncertainty of the pandemic [9], participants in this study reported using food to manage the anxiety and stress of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this increase in food consumption was common to many, it may also reflect the use of a familiar coping strategy: historically, Black women report coping with negative emotions by increasing in their eating behaviors [20,21,22]. For example, Black women have reported using high-fat and high-energy foods to cope with daily feelings of stress, boredom, loneliness, and other negative emotions [23]. In another study, Black women described emotion-based eating (i.e., eating as a response to emotion instead of hunger) as a strategy to deal with stress [20]. Further, Black women may also experience cultural norms that implicitly condone overeating as an acceptable way to manage feelings [22]. Given the confluence of factors affecting disordered eating behaviors among Black women, the additional stressors of COVID-19 presented a particularly difficult environment for managing these behaviors.

Influence of environment on eating choices

Participants in our study reported that being at home or spending more time in a triggering environment, or a place with easier access to food increased binge-eating. Indeed, participants noted that challenges managing their food intake—often influenced by stockpiling food due to uncertainty over food availability—and increased availability and access led to increased food consumption. Overall, many of our participants found it challenging to manage their binge-eating behaviors in these conditions, consistent with previous literature reporting symptom deterioration among eating disorder patients during the COVID-19 pandemic [18, 24]. However, in a qualitative study conducted in late summer of 2020, and comprised predominately White participants with similar binge-eating behaviors, results on the influence of the home environment were mixed [6]. About 30% of Frayn et al. study sample noted symptom improvement, citing that confinement at home reduced access to triggering foods, and led to fewer binges and less overeating. In contrast, though 40% of the participants in our study reported positive effects from the pandemic, none reported any symptom improvement [19]. The differences in symptom improvement between these two studies may be related to the period when the studies were conducted, with the Frayn et al. study [6] taking place in the summer, during a period when rates of infection rates of COVID-19 were subsiding, and anxiety may have lessened. Future research should examine the change in eating behaviors over time to assess factors that may contribute to perceived increases and decreases in food consumption.

Structure

Participants in this study noted the challenges they experienced managing their food intake due to the lack of daily structure and routine resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, scholars have noted that a lack of clear routines and a lack of separation between work and home may increase risk of engaging in ED behaviors [7]. In this study, that observation was further corroborated by the reflections of participants, several of whom noted various disruptions to regular eating behaviors, increased emotional eating, and staying up later than normal. Working from home created challenges for our participants, some of which other studies have also recognized. For example, in a qualitative study examining the impact of COVID-19 on individuals in the United Kingdom, participants noted that without the separation of the workday and home life, mealtime routines were interrupted, which risked making disordered eating behaviors more severe [25]. Furthermore, in a sample of adult patients with anorexia nervosa, participants noted that the inability to engage in routines that once brought comfort brought restlessness and a lack of purpose, creating further challenges to the management of their eating behaviors [26].

Positive effects/silver linings

Though participants’ experiences of managing their eating were incredibly challenging due to the limitations imposed by COVID-19, several participants did note some “silver linings” or positive outcomes of those limitations, including the ability to cook healthier foods at home, increased interactions with their social support system, and feeling less stigma when engaging in exercise in their home. Indeed, another study similarly found that staying home actually led some individuals to feel as if they had more control over their environment and food options, leading to positive changes in their binge-eating symptoms [6]. In fact, according to another study, staying at home forced those with eating disorders to develop alternative coping strategies, including consuming more meals prepared at home and increasing their consumption of fruits and vegetables [27].

Strength and limits

Due to the nature of qualitative research, personal biases could have impacted our interpretation of the interview data. Additionally, given that all participants were Black women from one southeastern state, the results have limited generalizability due to our homogenous, small sample. Further, because participants were interviewed for this study during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, our data may not have captured how experiences with eating may have shifted as the pandemic progressed. It is likely that eating behavior worsened into the first year of the pandemic. However, despite these limitations, this study is the first to describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating behaviors among Black American women reporting binge-eating and represents a foundational step toward better supporting this vulnerable population in a particularly challenging context.

Conclusion

This study focused on unique impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on binge-eating among Black American women. The results of this study may be useful for developing treatments tailored to Black women who binge-eat. Future research should focus on the impact of COVID-19 on Black women managing other types of disordered eating, as well as examine longitudinal changes in eating behavior to capture salient changes that occurred as the pandemic progressed. Future research should also utilize a larger, more nationally based sample to capture additional experiences managing disordered eating during stressful periods.

What is already known on this subject?

COVID-19 has had a detrimental impact on symptoms of eating disorders. Rates of binge-eating have increased. Data for this research, however, have come from predominately White samples.

What do we now know as a result of this study that we did not know before?

This study sheds light on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black women reporting binge-eating, a group that has been particularly adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, both in prevalence and mortality. This population has also been historically underserved by eating disorder research and treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the impact of COVID-19 on the eating behaviors of Black women who report disordered eating behaviors. This study confirms previously known factors affecting eating behaviors and offers a framework to guide the interpretation of the impact of COVID-19 on this population.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ford T, Reber S, Reeves RV (2020) Race gaps in COVID-19 deaths are even bigger than they appear. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/16/race-gaps-in-covid-19-deaths-are-even-bigger-than-they-appear/. Accessed 28 April 2022

Reyes MV (2020) The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black Americans. Health Hum Rights J 22(2):299–307

Poteat T, Millett GA, Nelson LE, Beyrer C (2020) Understanding COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities among black communities in America: the lethal force of syndemics. Ann Epidemiol 47:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.004

Hill L, Artiga S (2022) COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity: Current data and changes over time. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-and-deaths-by-race-ethnicity-current-data-and-changes-over-time. Accessed 19 July 2022

Gur RE, White LK, Waller R, Barzilay R, Moore TM, Kornfield S, Njoroge WFM, Duncan AF, Chaiyachati BH, Parish-Morris J, Maayan L, Himes MM, Laney N, Simonette K, Riis V, Elovitz MA (2020) The disproportionate burden of the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant black women. Psychiatry Res 293:113475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113475

Frayn M, Fojtu C, Juarascio A (2021) Covid-19 and binge eating: Patient perceptions of eating disorder symptoms, tele-therapy, and treatment implications. Curr Psychol 40(12):6249–6258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01494-0

Rodgers RF, Lombardo C, Cerolini S, Franko D, Omori M, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Linardon J, Courtet P, Guillaume S (2020) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorder risk and symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 53(7):1166–1170. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23318

Touyz S, Lacey H, Hay P (2020) Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. J Eat Disord 8(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00295-3

Thompson-Brenner H, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Grilo CM, Boisseau CL, Roehrig JP, Richards LK, Bryson SW, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, Devlin MJ, Gorin AA, Kristeller JL, Masheb R, Mitchell JE, Peterson CB, Safer DL, Striegel RH, Wilfley DE, Wilson GT (2013) Race/ethnicity, education, and treatment parameters as moderators and predictors of outcome in binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 81(4):710–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032946

Cachelin FM, Rebeck R, Veisel C, Striegel-Moore RH (2001) Barriers to treatment for eating disorders among ethnically diverse women. Int J Eat Disord 30(3):269–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1084

Castellini G, Cassioli E, Rossi E, Innocenti M, Gironi V, Sanfilippo G, Felciai F, Monteleone AM, Ricca V (2020) The impact of COVID-19 epidemic on eating disorders: A longitudinal observation of pre versus post psychopathological features in a sample of patients with eating disorders and a group of healthy controls. Int J Eat Disord 53(11):1855–1862. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23368

Christensen KA, Forbush KT, Richson BN, Thomeczek ML, Perko VL, Bjorlie K, Christian K, Ayres J, Wildes JE, Mildrum Chana S (2021) Food insecurity associated with elevated eating disorder symptoms, impairment, and eating disorder diagnoses in an American University student sample before and during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Eat Disord 54(7):1213–1223. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23517

Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O (2017) Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qual Nurs Res 4:2333393617742282

Sandelowski M (2000) Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res Nurs Health 23(3):246–255

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 16(4):363–370

Cecchetto C, Aiello M, Gentili C, Ionta S, Osimo SA (2021) Increased emotional eating during COVID-19 associated with lockdown, psychological and social distress. Appetite 160:105122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105122

Flaudias V, Iceta S, Zerhouni O, Rodgers RF, Billieux J, Llorca PM, Boudesseul J, de Chazeron I, Romo L, Maurage P, Samalin L, Bègue L, Naassila M, Brousse G, Guillaume S (2020) COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and problematic eating behaviors in a student population. J Behav Addict 9(3):826–835. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00053

Termorshuizen JD, Watson HJ, Thornton LM, Borg S, Flatt RE, MacDermod CM, Harper LE, Furth EF, Peat CM, Bulik CM (2020) Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with self-reported eating disorders: A survey of ~1,000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. Int J Eat Disord 53(11):1780–1790. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23353

Bakaloudi DR, Barazzoni R, Bischoff SC, Breda J, Wickramasinghe K, Chourdakis M (2021) Impact of the first COVID-19 lockdown on body weight: A combined systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.04.015

Cox TL, Zunker C, Wingo BC, Jefferson WK, Ard J (2011) Stressful life events and behavior change: a qualitative examination of african american women’s participation in a weight loss program. Qual Rep 6(3):622–634

Goode RW, Cowell MM, Mazzeo SE, Cooper-Lewter C, Forte A, Olaiya OI, Bulik CM (2020) Binge eating and binge-eating disorder in Black women: A systematic review. Int J Eat Disord 53(4):491–507. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23217

Kumanyika S, Whitt-Glover MC, Gary TL, Prewitt TE, Odoms-Young AM, Banks-Wallace J, Samuel-Hodge CD (2007) Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Prevent Chron Dis 4(4):A112

Chang MW, Nitzke S, Guilford E, Adair CH, Hazard DL (2008) Motivators and barriers to healthful eating and physical activity among low-income overweight and obese mothers. J Am Diet Assoc 108(6):1023–1028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.03.004

Branley-Bell D, Talbot CV (2020) Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and UK lockdown on individuals with experience of eating disorders. J Eat Disord 8(1):1–12

Brown S, Opitz MC, Peebles AI, Sharpe H, Duffy F, Newman E (2021) A qualitative exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders in the UK. Appetite 156:104977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104977

Clark Bryan D, Macdonald P, Ambwani S, Cardi V, Rowlands K, Willmott D, Treasure J (2020) Exploring the ways in which COVID-19 and lockdown has affected the lives of adult patients with anorexia nervosa and their carers. Eur Eat Disord Rev 28(6):826–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2762

Coulthard H, Sharps M, Cunliffe L, van den Tol A (2021) Eating in the lockdown during the Covid 19 pandemic; self-reported changes in eating behaviour, and associations with BMI, eating style, coping and health anxiety. Appetite 161:105082

Ramalho SM, Trovisqueira A, de Lourdes M et al (2022) The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on disordered eating behaviors: the mediation role of psychological distress. Eat Weight Disord 27:179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01128-1

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the participants who gave of their time to participate in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by K23DK129832 and the University Research Council at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by HM, MT, DC, LB, and TN. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RWG, HM, LB, DC, MT, and TN. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CM Bulik reports: Shire (grant recipient, Scientific Advisory Board member); Lundbeckfonden (grant recipient); Pearson (author, royalty recipient); Equip Health Inc. (Clinical Advisory Board). The other authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study (IRB 18-1314) was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained by all individual participants in the study.

Consent to publish

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Goode, R.W., Malian, H., Samuel-Hodge, C. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on Black women who binge-eat: a qualitative study. Eat Weight Disord 27, 3399–3407 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01472-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01472-w