Abstract

Studies have increasingly suggested that autistic students face a heightened risk of bullying. Understanding the underlying factors for high rates of bullying victimization among autistic students is crucial for intervention, but the complexity of bullying and the heterogeneity of ASD (autism spectrum disorder) traits have made it challenging to explain these factors. Hence, this study systematically reviewed and summarized findings in this area, providing recommendations for intervention. It synthesized 34 studies investigating the predictive variable of bullying victimization among autistic students. Our review observed the role of schools, parents, and peers and of individual variables with respect to autistic traits and behavioral difficulties. We then proposed prevention and intervention strategies against bullying victimization toward autistic students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bullying is a form of aggressive behavior intended to cause harm (Smith, 2016). It satisfies three additional criteria: (1) intentionality, (2) some repetition, and (3) a certain imbalance of power, in which the targeted student faces challenges in self-defense (Olweus, 2013). Data from two international surveys (i.e., the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children Survey and the Global School-Based Student Health Survey) have shown that 32% of students have experienced bullying in some form by their peers at school on one or more days in the past month (UNESCO, 2019). School bullying can be devastating for the victim (UNESCO, 2019), and its direct consequences range from reduced concentration during classes to frequent absences, avoidance of school engagements, truancy, and the possibility of dropping out of school altogether (Dake et al., 2003). Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis has found a strong causal association between bullying victimization and mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, poor general health, and suicide (Moore et al., 2017), making the eradication of school bullying a challenging global imperative (Shiva Kumar et al., 2017; UNESCO, 2019).

A growing body of literature indicates that autistic students face a higher risk of being bullied than typically developing students and those with other disabilities, such as learning disabilities, behavioral or mental health disorders, or cystic fibrosis (Maïano et al., 2016; Park et al., 2020; Rowley et al., 2012; Twyman et al., 2010). Recent meta-analyses have reported that the pooled prevalence estimates for victimization were 44% and 67% (Maïano et al., 2016; Park et al., 2020). For children experiencing difficulty in establishing and maintaining peer friendships, ostracism may be particularly devastating (Twyman et al., 2010). Bullying victimization among autistic students has been shown to be a predictor of suicide (Holden et al., 2020), internalized mental health problems (Rodriguez et al., 2021), and adolescent and adulthood psychopathology (Ferrigno et al., 2022). The consistent high prevalence of bullying victimization indicates the urgent need for studies to identify its root and develop effective, evidence-informed interventions (Humphrey & Hebron, 2015; Maïano et al., 2016). We believe that understanding how and why autistic students become targets of bullying could help prevent bullying and its negative impacts, improve their interpersonal relationships, and enhance their well-being. However, the heterogeneity of ASD traits and the complexity of bullying make it difficult to theoretically explain the mechanisms behind bullying (Carrington et al., 2017; Hong & Espelage, 2012).

Studies have offered several hypotheses for the putative factors behind the heightened risk of bullying victimization among autistic students. First, Humphrey and Symes (2011) proposed a reciprocal effects peer interaction model (REPIM) to understand how a dual route mechanism that is linked to peer interactions may lead to exposure to bullying and the negative social outcomes of victimization among autistic students. According to REPIM, social outcomes are caused by two interrelated factors: problems in social cognition leading to a lack of sufficient skills to build relationships and a lack of awareness and understanding by the peer group, leading to a reduced acceptance of difference. The combination of the two factors reduces interpersonal interactions, friendships, and social support for autistic students, which in turn leads to increased rejection, bullying, isolation, and loneliness. These outcomes go on to generate reciprocal effects and create a vicious cycle in which autistic students have reduced motivation to make social contact, and their peers have reduced opportunities to learn about ASD (Humphrey & Hebron, 2015).

Another explanation comes from stigma-based bullying research, as young people living with socially devalued characteristics are found to experience bullying more frequently than other youth (Earnshaw et al., 2018). ASD is a lifelong condition, characterized by deficits in social communication and social interaction and restricted, repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Indeed, research has found certain stereotypes associated with ASD, including poor social skills, withdrawal, poor communication, and a difficult personality or engagement in difficult behavior, which are all perceived as negative health-related traits (Wood & Freeth, 2016). This stigma arises from the experience or reasonable expectation of negative social judgments against a person or group associated with a specific health issue (Weiss & Ramakrishna, 2006). This is characterized by social processes including exclusion, rejection, blame, or devaluation, which are highly associated with bullying (Earnshaw et al., 2018; Weiss & Ramakrishna, 2006).

Finally, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework offers a broad perspective for the understanding of the context of bullying among autistic students (Bronfenbrenner, 2005; Humphrey & Hebron, 2015). Factors associated with bullying victimization can be classified into the contexts of micro- (e.g., positive family interactions, social support from peers, and school safety), meso- (e.g., teacher involvement in promoting positive classroom environments or addressing bullying), exo- (e.g., safe and supportive neighborhood), macro- (e.g., societal attitudes toward neurodiversity or policy shift for inclusivity within education for autistic students), and chrono (e.g., changes in family structure) system levels (Hong & Espelage, 2012). Therefore, adopting a social-ecological perspective is crucial for designing bullying prevention and intervention programs and thoroughly evaluating them (Hong & Espelage, 2012).

Researchers have found that the driving factors of bullying victimization among autistic students include ASD traits, social vulnerability, behavior problems, co-occurring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, emotion, academic achievement, educational setting, school transportation, parents’ mental health, parental engagement and confidence, socioeconomic status, and social support (Humphrey & Hebron, 2015; Schroeder et al., 2014; Sreckovic et al., 2014). In a closely timed meta-analysis, researchers found a positive relation between social interaction and communication deficits, externalized and internalized symptoms, integrated inclusive school settings, and higher victimization (Park et al., 2020).

Although several reviews and meta-analyses have sought to clarify the factors influencing bullying victimization among autistic students, some limitations and unresolved aspects must be further scrutinized. First, previous reviews have left several open questions: (1) the role of school setting and more contextual factors in victimization must be further clarified (Schroeder et al., 2014). (2) The risk of school bullying specifically associated with the characteristics of autistic school-aged youth must be explained (Maïano et al., 2016). (3) The reason for the negative correlation between autistic traits and bullying victimization in certain circumstances must be identified (Schroeder et al., 2014). Second, from a theoretical perspective, only Humphrey and Hebron’s (2015) review has linked factors of bullying victimization of ASD students to theoretical frameworks. In particular, most empirical studies in this field have formulated research hypotheses that feature weak theoretical foundations based on phenomena and the results of other empirical research. This study extensively integrates factors with existing theory and broadens the scope of research opportunities in that domain. Moreover, all existing reviews have ignored the results of qualitative studies, even though they may also occupy some space in this field. Current research may contribute to the knowledge regarding the nature of the problem by incorporating qualitative studies that explicitly delineate variables related to bullying victimization among autistic students. Taking these limitations as a starting point, the current study is motivated by the following research questions:

-

What contributes to the divergence in results regarding the relationship between autistic traits and bullying victimization?

-

What factors influence the bullying victimization of autistic students?

Method

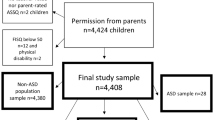

In this systematic review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Figure 1 summarizes the stages of this review in a flowchart. The review was not registered; the recommendation of PRISMA-P to include in a systematic review protocol is described in the “Introduction” and “Method” sections (Moher et al., 2015).

Search strategy results based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021)

Identification

In June 2023, we searched for potentially relevant studies from the Web of Science, PubMed, APA PsycInfo (Ovid), and ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) scientific databases with no time restrictions and combining either the title, abstract, or keywords. The search strategy included every possible combination of the two sets of keywords: (a) (“Autis*” OR “autism” OR “ASD” OR “Asperger”), (b) (“bully*” OR “victim*” OR “victimization” OR “aggression” OR “harassment” OR “violence” OR “exclusion”). The search was limited to peer-reviewed journals. In the initial stage, we identified 894 records consisting of 190 records from the Web of Science, 129 from ERIC, 201 from PubMed, and 374 from PsycINFO (Ovid).

Screening

All 538 duplicates identified were manually removed. At this stage, we identified the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (1) only qualitative and quantitative studies from journal articles were included, (2) only papers written in English were included, (3) studies with no autistic participants were excluded, and (4) studies that do not refer to bullying victimization were excluded. During this phase, to ensure that no potentially valuable articles were omitted, all of the studies that could not be definitively excluded from their titles and abstracts alone were incorporated into the next stage. A total of 105 papers were selected for the eligibility phase.

Eligibility

The full text of each paper was downloaded and rated. At this stage, the exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies that do not mention peer bullying victimization of autistic students, (2) studies that do not examine factors of bullying victimization, (3) studies involving autistic participants and participants with other disabilities or without disabilities except those that segregated data for autistic students, and (4) in instances where researchers conducted multiple studies using the same dataset, only the study that provided the most comprehensive reporting was included, or the series of studies will be consolidated and then reported. Following these criteria, 34 papers remained and were included in the present systematic review; these included 30 quantitative studies, 3 qualitative studies, and 1 mixed-methods study.

Quality Appraisal

The first author conducted a quality appraisal of the included literature using the Checklist for Assessing the Quality of Quantitative Studies (QualSyst), developed by Kmet et al. (2004). QualSyst provides separate checklists for quantitative studies (14 items) and qualitative studies (10 items). The mixed-methods study was evaluated using both checklists. QualSyst accommodates variations in experimental design by employing a three-point scoring system (not applicable/no = 0, partial = 1, and yes = 2). The summary score is the total score divided by the total score possible sum. We employed a threshold recommended by Norberg et al. (2016), with scores of 0.70 or higher being considered to indicate sufficient quality. In accordance with other qualitative reviews, studies were not excluded or stratified by risk of bias.

Synthesis

The first author extracted relevant information from each included study, including participant data (sample size, gender, age, and ASD diagnosis), study design, characteristics of bullying victimization studies (informants and bullying measures), and examined factors. To maintain consistency with previous research, the factors of bullying victimization were classified based on the following dimensions: individual vs. contextual factors and protective vs. risk factors (Humphrey & Hebron, 2015; Sreckovic et al., 2014). Taking into account the varying definitions of some individual factors (e.g., autism traits, social difficulties), we annotated the factors sharing the same names but having distinct definitions with measurement tools. A summary of the findings was then discussed and revised between authors.

Results

General Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the 34 peer-reviewed journal articles that were included in our review. These studies were published between 2011 and 2022, consisting of 25 quantitative studies following a cross-sectional research design and 5 that adopted a longitudinal research design. Additionally, three studies employed a purely qualitative approach, and one study utilized a mixed-methods design. The sample sizes of the quantitative studies ranged from 22 to 112, while those of the qualitative studies ranged from 5 to 36. Due to gender-related disparities in autism prevalence, male samples were predominant in all studies except for one that intentionally controlled for gender differences (Greenlee et al., 2020). Considering the participants’ ASD diagnoses, 19 studies provided a detailed description of the diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM-5; Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, etc.). Specific diagnostic criteria were not disclosed by 11 studies; however, these stated that participants had a clinical diagnosis or confirmed the diagnosis through credible information sources (e.g., school district records, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service records). Four studies only briefly acknowledged the presence of an autism diagnosis or condition in participants, without offering detailed information. The details are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Regarding the informants of bullying victimization, 25 studies collected data from single informants (self-reported, n = 10; parent-reported, n = 13; and peer-reported, n = 2), and 9 studies collected data from multiple informants (self- and parent-reported = 5; self- and peer-reported = 1; parent- and teacher-reported = 1; and self-, parent-, and teacher-reported = 2). All articles measured bullying victimization and its associated variables. However, seven studies did not use validated scales and instead employed true–false questions or text mining for interview content. In these studies, bullying victimization was coded as a binary variable.

Quality Appraisal

Of the 29 quantitative studies reviewed, 26 were assessed as being of sufficient quality (summary score higher than 0.7). All three qualitative studies met the established standards for acceptable quality. In the mixed-methods study, the quantitative component was determined to be of sufficient quality, while the qualitative component was of limited quality. The summary scores for the quantitative checklist ranged from 0.59 to 0.95, with an average of 0.82, while those for the qualitative checklist ranged from 0.60 to 0.85, with an average of 0.74. Detailed scores for each included study are presented in supplementary tables.

Factors Related to the Bullying Victimization of Autistic Students

In the reviewed literature, we found 34 studies examining individual factors associated with the bullying victimization of autistic students. Among these studies, 19 examined individual factors exclusively, 14 studies investigated both individual and contextual factors, and only 1 focused solely on contextual factors.

Individual Factors

Studies examined factors such as demographic variables, autistic traits, co-occurring conditions, internalized symptoms, externalized symptoms, and behavioral difficulties. Although these were either protective or risk factors of bullying victimization, studies have inconsistently found that some functioned as both risk and protective factors.

Demographic Variables

Current findings on the relation between age, gender, and bullying victimization among autistic students have been inconsistent. In Cappadocia et al.’s (2012) study, binomial logistic regression showed that bullying victimization among autistic students occurs more frequently among younger students. Simply put, autistic students are less likely to be bullied as they grow older. This finding has been supported by later studies (Matthias et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2015). Research has also found that younger age is linked to specific types of bullying victimization, such as physical victimization (Kloosterman et al., 2014) and relational victimization (Storch et al., 2012). However, other studies have reported inconsistent results as well. For example, Hebron and Humphrey (2014) found that, as autistic students age, their victimization, as reported by teachers and parents, increases significantly, which is also supported by subsequent findings (Holden et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2021). For specific types of bullying victimization, older age is positively associated with being ignored more (Adams et al., 2020). Additionally, five studies reported that age is not a significant predictive factor for victimization (Ashburner et al., 2019; Fink et al., 2018; Forrest et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2019, 2021). Regarding grade level, middle school autistic students are more likely to be victimized by bullying than those in elementary and high school (Zablotsky et al., 2012, 2013, 2014).

In terms of gender, 18 studies reported a relation between gender and bullying victimization. Two of these studies indicated that female participants reported higher levels of victimization (Adams et al., 2014; Holden et al., 2020). However, in the remaining 16 studies, the effect of gender was not found to be significant. The only study with an equal number of male and female participants found that girls reported more experiences of relational aggression than boys did, while boys reported more instances of overt victimization, but these differences were not statistically significant.

With regard to socioeconomic status, autistic students who live below 200% of the federal poverty level (Forrest et al., 2020) and those who receive free and reduced meals also experienced more bullying victimization (Zablotsky et al., 2013). Two studies found no significant association between household income and bullying victimization among autistic students (Matthias et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2015).

In another two studies, racial-minority autistic children experienced more instances of bullying victimization (Forrest et al., 2020; Zablotsky et al., 2014). However, in two other studies conducted in the USA where White participants were the predominant proportion (79.5% and 65.2%), African American and any other Black participants showed the lowest levels of bullying victimization in logistic regression. In addition, no significant difference in bullying victimization was observed between White participants and individuals from other racial backgrounds (Matthias et al., 2021; Sterzing et al., 2012). One study that involved diverse ethnic backgrounds (i.e., White, Black, Asian, and mixed) found no significant correlation between race and instances of bullying victimization (Holden et al., 2020).

ASD Diagnosis and Autistic Traits

Among the included studies, Zablotsky et al. (2014) compared bullying victimization among students diagnosed with autism, Asperger’s syndrome,Footnote 1 and other ASD. They found that autistic students who were victims of bullying were more likely to be diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome and less likely to be diagnosed with autism (Zablotsky et al., 2013, 2014).

Furthermore, five studies examined the positive relation between higher autistic traits and bullying victimization (Adams et al., 2014; Chou et al., 2019; Rodriguez et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2015; Zablotsky et al., 2014). Regarding specific autism traits, some inconsistent results were observed.

Cappadocia et al. (2012) employed the Autism-Spectrum Quotient and found that bullying experiences were positively correlated with communication difficulties but had no association with social skills deficit. Sterzing et al. (2012) found that lower social skills and any form of conversational ability were positively linked to bullying victimization. Studies that used the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire found a positive correlation between peer problems and bullying victimization in autistic students (Begeer et al., 2016; Fink et al., 2018). Fink et al. (2018) also found that prosocial behavior served as a protective factor against bullying victimization. Chou et al. (2019) used the Social Responsiveness Scale and found that deficits in social communication and social emotion are positively related to parent-reported bullying victimization. They also found that more severe deficits in social communication were also positively correlated with self-reported victimization. Greenlee et al. (2020) employed the Social Responsiveness Scale-2 and observed that deficits in social communication significantly affected relational victimization for both male and female participants, while deficits in social cognition and social motivation affected relational victimization in female samples only. Forrest et al. (2020) examined the associations between children’s social behavior and bullying victimization, finding that not being optimally tuned in to the social situation and resistance to changes were significantly associated with more bullying victimization. Matthias et al. (2021) found that autistic students with difficulty speaking clearly or who mentioned “other people like me” were more likely to be victims of bullying. Moreover, social problems measured by the Child Behavior Checklist served as risk factors for bullying victimization (Hsiao et al., 2022; Hunsche et al., 2022). However, studies that used the social domain of the Standardized Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule showed a negative correlation between social impairment and bullying victimization (Hunsche et al., 2022; Rowley et al., 2012). Within qualitative research, social differences are a barrier to social support access (Ashburner et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2016; Humphrey & Symes, 2010).

Regarding restricted and repetitive behaviors, Adams et al. (2014) found a positive relation between repetitive behavior, as measured by the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised, and parent-reported bullying victimization. Chou et al. (2019) employed the Social Responsiveness Scale and also found that autism mannerisms were positively associated with bullying victimization. Greenlee et al. (2020) used the Social Responsiveness Scale-2 and observed that restricted and repetitive behaviors had a positive effect on relational victimization exclusively in female subjects. However, Adams et al. (2020) identified repetitive behavior as a protective factor and found reduced verbal bullying victimization among autistic students.

Co-occurring Conditions

Among autistic students, co-occurring conditions with other disorders form a risk factor for bullying victimization. Most co-occurring conditions that have been found to increase bullying victimization risk in autistic students include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, oppositional defiant disorder symptoms, obsessive–compulsive disorder, depression, and anxiety. Meanwhile, verbal tics were associated with lower levels of verbal bullying (Adams et al., 2020). In addition, to independent effects, a simultaneous experience of co-occurring conditions with more than two conditions further increases the risk of bullying victimization (Zablotsky et al., 2014). However, later studies have not consistently replicated this finding. Forrest et al. (2020) observed that individuals who have one co-occurring condition experienced higher levels of bullying than those with no co-occurring condition, but no significant difference was found between individuals with more than one co-occurring condition and those with none. In addition, Holden et al. (2020) found that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and antipsychotics prescribed to autistic students were also exposed to more bullying victimization.

Mental Health and Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties

Internalized symptoms were a risk factor for bullying victimization across three studies (Adams et al., 2014; Cappadocia et al., 2012; Zablotsky et al., 2013). Several studies have examined specific internalized symptoms, such as depression (Hwang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Storch et al., 2012), anxiety (Hwang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Sofronoff et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2015), and panic (Storch et al., 2012). Another study investigated the relations among anxiety, depression, and bullying victimization in male and female participants, showing a significant link between anxiety and depressive symptoms with bullying victimization in female subjects only (Greenlee et al., 2020). Additionally, social anxiety has also been shown to be positively associated with bullying victimization (Liu et al., 2021; van Schalkwyk et al., 2018).

We consolidated research findings on externalized symptoms and behavior difficulties because of the overlap between concepts (e.g., aggressiveness, impulsivity, and hyperactivity). Behavioral difficulties that were positively associated with bullying victimization included atypicality (e.g., hallucinations and delusional thoughts), attention problems (Hwang et al., 2018), and aggressive behavior (Hsiao et al., 2022; Hwang et al., 2018). As with aggression, autistic students who bullied others were also found to be bullied more (Kloosterman et al., 2014). In addition, ASD‑related behaviors, defined by Adams et al. (2020) as frequent meltdowns, poor hygiene, rigid rule-keeping, and self-injury, were also positively associated with bullying victimization. Although hyperactivity and conduct problems were found to be positively linked to bullying victimization, such an association was not significant based on a regression analysis (Fink et al., 2018; Hwang et al., 2018). With regard to emotional difficulties, anger (Rieffe et al., 2012; Sofronoff et al., 2011) and emotion management problems (Zablotsky et al., 2013) among autistic students were found to be positively associated with bullying victimization.

A notable longitudinal study found that Time 1 internalized and externalized symptoms were positively related to Time 1 bullying victimization, but neither internalized nor externalized symptoms at Time 1 had any significant effect on Time 2 victimization; meanwhile, victimization at Time 1 served as a predictive factor for subsequent internalized symptoms (Rodriguez et al., 2021).

Other Variables

Beyond the above categories are studies exploring the influence of several other individual factors. Studies that adopted a cognitive perspective found that difficulties in executive functions (Kloosterman et al., 2014) and facial emotion recognition (Liu et al., 2019) are positively associated with bullying victimization in autistic students. In the context of social interactions and school life, protective factors against bullying victimization for autistic students included social preference and popularity (Schrooten et al., 2018), whereas risks included loneliness (Storch et al., 2012) and social vulnerability (Sofronoff et al., 2011).

Empirical studies have examined social interactions and revealed unexpected findings in that autistic students with higher theory of mind (i.e., awareness of other’s thoughts and emotions) (Hunsche et al., 2022) and stronger self-liking tendency were more likely to be bullied (Matthias et al., 2021). A study based on clinical samples found that autistic children with a risk of abuse (moderate or high) and slightly higher Child Global Assessment Scores (i.e., better functioning across a range of psychological and social aspects) were more likely to be victimized by bullying (Holden et al., 2020). Finally, the experience of a higher number of total negative life events (e.g., death of a first-degree relative, serious illness or injury, and loss of a good educational assistant) is a risk factor associated with an increased likelihood of bullying victimization (Weiss et al., 2015).

Contextual Factors

A total of 15 studies examined contextual factors of bullying victimization among autistic students. Among these, 11 were quantitative studies, 3 were qualitative studies, and 1 was a mixed-methods study. Context factors of bullying victimization revolved around the roles of four main entities: schools, teachers, parents, and peers.

Roles of the School and Teacher

Special schools are perceived as protective factors against bullying victimization (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014; Zablotsky et al., 2013), while autistic students who are enrolled in mainstream schools and public schools experience higher levels of bullying (Rowley et al., 2012; Zablotsky et al., 2013). More classes in general education classrooms were also positively correlated with bullying victimization among autistic students (Sterzing et al., 2012; Zablotsky et al., 2014). Another study that investigated the relation between bullying and the school climate suggested a negative effect of bullying victimization among autistic students on parents’ perceived school climate (Zablotsky et al., 2012). Empirical evidence indicated a positive correlation between the use of public/school transportation and increased bullying victimization (Hebron et al., 2015). Finally, one study that explored teachers’ roles found that their actions to improve attitudes toward autistic students can mitigate the students’ bullying victimization (Falkmer et al., 2012).

In a qualitative study, Hebron et al. (2015) proposed that a safe and supportive school environment, along with academic support (e.g., teaching assistants) and a positive school ethos (i.e., a clear and effective anti-bullying policy), are protective factors against bullying victimization among autistic students. Taking a relative perspective, Cook et al. (2016) pointed out that in mainstream schools, a lack of understanding of bullying in the school culture, insufficient staff and resources, and the school’s failure to address bullying are risk factors for bullying victimization among autistic students.

The Role of the Caregivers

The results of two logistic regression analyses revealed that autistic students whose parents have mental health problems were more likely to experience higher levels of bullying victimization (Cappadocia et al., 2012; Holden et al., 2020). Another study identified parental stress as a risk factor in predicting bullying victimization (Weiss et al., 2015). In addition, studies have demonstrated the protective function of maternal education duration (Chou et al., 2019), parental engagement, and confidence (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014) against bullying victimization in autistic students.

The Role of Friends

Studies investigating the role of friendship have identified having fewer friends at school (Cappadocia et al., 2012) as a risk factor, whereas meeting with friends at least once a week was a protective factor (Sterzing et al., 2012). Teacher-reported peer relationships of autistic students were also found to negatively predict bullying victimization although this effect was not significant in parent-reported data (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014). Each of the qualitative studies highlighted the crucial role of friendships; positive relationships (with adults and peers) may mitigate bullying victimization (Hebron et al., 2015; Humphrey & Symes, 2010), and having a supportive friend was considered protective (Cook et al., 2016).

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed research that examined factors affecting bullying victimization among school-aged students diagnosed with ASD. Compared to the perspectives adopted by studies that reviewed empirical research until 2013, studies in this field in the past decade have not only duplicated but also questioned some widely accepted understandings.

Individual Factors

With regard to the effect of an ASD diagnosis, an Asperger’s diagnosis could be perceived as a risk factor, whereas autism might be considered a protective factor against victimization (Zablotsky et al., 2014). Zablotsky et al. (2014) also observed an increased perpetration and perpetration-victimization among students with Asperger’s syndrome. They pointed out that autistic students who have low support needs tend to integrate into mainstream schools, leading to increased interactions with typically developing students and a higher likelihood of becoming targets for bullying. Studies have also indicated that individuals with Asperger’s syndrome exhibit distinct communication and patterns of social difficulties described as active but odd (Ghaziuddin, 2008; Kaland, 2011), and the active nature might increase the likelihood of exposure to bullying. Meanwhile, when teenagers believe that bullying occurs because victims are odd, different, or deviant, it increases their involvement in bullying situations as either bullies or reinforcers (Thornberg, 2013).

Most studies have continued to examine autistic traits (e.g., communication, social, and behavior difficulties), psychiatric co-occurring conditions, and internalized and externalized symptoms as risk factors that influence bullying victimization. In consensus with previous reviews, ASD diagnosis and autistic traits carry the risk of bullying victimization (Schroeder et al., 2014; Sreckovic et al., 2014). Given the tremendous phenotypic heterogeneity in autistic adolescents, these traits show as difficulties in understanding subtext, challenges in interpreting others’ emotional states, differences in social interactions, and engaging in repetitive behaviors (Adams et al., 2020; Wood & Freeth, 2016). According to Social Identity Theory, these differences may lead to autistic students being perceived as an identity-based minority group that is affected by a stigmatized social status, which in turn diminishes their well-being (Perry et al., 2022). Typically developing students may evaluate their ingroup members (other typical development students) more favorably and prefer them to possess more social power than members of outgroups (autistic students) (Hewstone et al., 2002; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). This resulting power imbalance may increase the risk of stigma-based bullying (Earnshaw et al., 2018). Moreover, ASD also commonly co-occurs with psychiatric co-occurring conditions, intellectual disability, and internalized symptoms (Matson & Goldin, 2013; Muratori et al., 2019). Many of the included studies found that psychiatric co-occurring conditions, intellectual disability, and internalized symptoms increased bullying victimization risk among autistic students and that autistic students who have multiple co-occurring conditions are believed to have a higher risk of bullying victimization (Zablotsky et al., 2014). Co-occurring conditions can lead to multiple stigmatized conditions (intersectional stigma), which may further increase their vulnerability (Oexle & Corrigan, 2018; Turan et al., 2019). Co-occurring conditions have also been found to widen the behavioral differences between autistic students and typically developing students (Casanova et al., 2020).

A considerable number of studies has found that overt behavior related to ASD and co-occurring conditions may increase the likelihood of being a target of bullying (Adams et al., 2014, 2020; Fink et al., 2018; Greenlee et al., 2020; Hebron & Humphrey, 2014; Hsiao et al., 2022; Hwang et al., 2018; Sofronoff et al., 2011). Because ASD is referred to as invisible, teachers and classmates who lack knowledge about it may inaccurately attribute the behaviors of autistic students and feel confused about understanding and getting along with them (Thompson-Hodgetts et al., 2020). For example, when the controllability of restricted and repetitive behavior is perceived as high, teachers reported significantly reduced sympathy and greater frustration (Welsh et al., 2019). Besides sympathy and frustration, attribution theory indicates that beliefs about controllability regarding others’ behaviors can evoke emotions such as anger, envy, gratitude, jealousy, and schadenfreude (Weiner, 2010). Multiple studies have confirmed that these firsthand emotional experiences and the emotional intelligence of individuals predict bullying roles, which are highly related to bullying occurrence and repetition (Imuta et al., 2022; Schokman et al., 2014). Moreover, autistic students are less sensitive in recognizing the intensity of others’ facial emotions (Kennedy & Adolphs, 2012), which may heighten the challenge of responding appropriately and increase their risk of being bullied (Liu et al., 2019). In an unexpected finding, Adams et al. (2020) revealed that repetitive behaviors and verbal tics were associated with a lower likelihood of verbal bullying victimization. The authors posited that this outcome may be linked to the moderating effect of intelligence quotient; however, this conjecture remains unvalidated.

Finally, studies widely agree that social communication differences are the core of ASD, and these can also lead to an increase in bullying, either directly or indirectly (Humphrey & Hebron, 2015). According to the REPIM proposed by Humphrey and Symes (2011), not only insufficient relationship-building skills of autistic students but also the lack of awareness and the reduced acceptance of difference by the peer group reduces the quality and frequency of their peer interactions, resulting in bullying, social rejection, feelings of loneliness, and social isolation. These negative social outcomes then diminish the motivation of autistic students to engage in further peer interactions, creating a pattern of avoidance and solitary behavior that provides no adequate opportunities for developing social and communicative skills. The REPIM framework effectively explains the correlations that empirical studies found between social differences (Hsiao et al., 2022; Hunsche et al., 2022), peer problems (Begeer et al., 2016; Fink et al., 2018), social skills (Sofronoff et al., 2011; Sterzing et al., 2012), communication difficulties (Cappadocia et al., 2012; Chou et al., 2019; Matthias et al., 2021), loneliness (Storch et al., 2012), social preference, popularity (Schrooten et al., 2018), and bullying victimization. Despite the theoretical path and the accumulation of empirical evidence supporting the positive relation between social differences and bullying victimization, some noteworthy contradictory findings have also emerged. In Rowley et al.’s (2012) study, social impairment measured using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule was negatively correlated with bullying victimization, and this result was subsequently replicated in another study that used the same measurement (Hunsche et al., 2022). The authors have offered two possible explanations for these findings. First, children with slight social differences might be more sensitive to subtle instances of bullying and exclusion by their peers and can therefore detect bullying victimization and report it to their parents, teachers, and researchers. Second, an alternative view suggests that children with higher social skills are more likely to actively engage in social interactions with their peers, leading them to interact more frequently with other children and increasing their chances of experiencing negative social situations such as teasing and bullying. Furthermore, it is important to note that there is a significant overlap between autistic students with slight social differences and those diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome. From the attribution theory, as we discussed above, violations of neurotypical expectations could be misattributed by neurotypical peers, evoke their negative emotional responses, and then influence their participant roles in bullying (Imuta et al., 2022; Schokman et al., 2014; Weiner, 2010).

The above discussion represents possible explanations for how ASD conditions may lead to bullying victimization. To explore the mechanisms of interaction among individual factors, Hsiao et al. (2022) designed a series of multiple mediation models with autistic traits, several behavioral difficulties, and withdrawal as mediating variables. They found that social problems are the sole significant mediator between autism diagnosis and victimization, while aggressive behavior is the only significant mediator between diagnosis and victimization-perpetration. Also worth noting is that recent studies have confirmed the positive relation between autistic traits and bullying victimization in the general population (Junttila et al., 2023; Stanyon et al., 2022). Simply put, autistic traits and autism diagnosis may separately influence bullying victimization.

Contextual Factors

Studies of contextual factors have focused on three main stakeholders: schools, parents, and peers. One research stream aimed to investigate objective factors such as school type, social isolation, and the use of public or school transportation, while another adopted a more socially and psychologically oriented approach, examining factors such as school climate, parental stress, and relationships with other students.

From a school perspective, autistic students who attend special schools experience less bullying victimization than those in mainstream schools (Hebron & Humphrey, 2014; Rowley et al., 2012; Zablotsky et al., 2013). Additionally, relative to private institutions, autistic students enrolled in public schools experienced more bullying victimization (Zablotsky et al., 2013). This phenomenon is explained by the school’s capacity to deliver support and adaptive education. For instance, in comparison with special schools, most students in mainstream schools are typically developing; consequently, these schools may encounter challenges in offering sufficient resources and staffing to effectively address the educational needs of autistic students (Cook et al., 2016). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis identified integrated inclusive school settings as a risk factor (Imuta et al., 2022). Besides school type, school climate is also considered crucial in effective bullying prevention (Wang et al., 2013). Studies included in the review found that school safety, support for autistic students, school ethos, and anti-bullying policies are protective factors, while a lack of understanding of school culture and failure to address bullying are risks (Ashburner et al., 2019; Cook et al., 2016; Hebron et al., 2015; Humphrey & Symes, 2010).

Parental mental health, engagement confidence, and the mother’s education level have been shown to be associated with bullying victimization among autistic students (Cappadocia et al., 2012; Chou et al., 2019; Hebron & Humphrey, 2014; Holden et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2015). These findings are consistent with those of typically developing students (Nocentini et al., 2019). Supportive families can mitigate their children’s victimization risk and protect them from the impact of stressful and traumatic experiences (Bowes et al., 2010; Rudolph et al., 2020).

Finally, the quantity of peers, frequency of interactions, and quality of relationships were negatively correlated with bullying victimization among autistic students (Cook et al., 2016; Hebron & Humphrey, 2014; Sterzing et al., 2012). Previous studies have demonstrated that a strong social network reduces one’s vulnerability to bullying. Meanwhile, the quantity and quality of friendships mitigate the negative outcomes of bullying victimization and increase resilience to peer victimization (Schacter et al., 2021). From the double empathy perspective, a budding friendship with autistic students could foster a motivation in non-autistic peers to repair an empathy disconnect, thereby mitigating the double empathy problem (a disjuncture in reciprocity between two differently disposed social actors) (Milton, 2012; Finke & Dunn, 2023). Gillespie-Smith et al. (2024) have also proposed that the processes of learning and understanding in relationships with friends who bridge neurocultures can bleed and blend the autistic-allistic border as conceptualized in double empathy. These findings highlight the significant role of friendship in altering neurotypical perceptions and biases, as well as influencing the social experiences of autistic individuals by reducing stigma and increasing acceptance (Morrison et al., 2019).

Prevention and Intervention Strategies

Hebron et al. (2015) proposed four key areas for action to prevent bullying: autistic students, peers, teachers and support staff, and school climate.

First, studies have emphasized that interventions for improving the social skills of autistic students should be tailored to their individual needs (Carrington et al., 2017; Humphrey & Hebron, 2015). Building on current findings, we suggest that educators and researchers consider the interests and talents of autistic students when developing teaching or intervention plans for them. Current evidence indicates that autistic students who have outside interests, talents, or higher social preferences and popularity are less likely to experience bullying (Cook et al., 2016; Schrooten et al., 2018). These findings indicate the importance of focusing on the interests and motivations of ASD students, supporting their strengths.

Second, improving the school climate is crucial. Schools must develop a zero-tolerance policy against bullying and clearly express to students their expectations of inclusivity and respect for diversity. School administrators must also encourage communication among teachers, students, and parents as well as engagement in school affairs and activities, which will help create a positive and healthy school climate and in turn enhance students’ education and health outcomes while reducing bullying incidents (Bear et al., 2014; Voight & Nation, 2016). A shared vision among teachers, staff, and students contributes to both relationships and the community and empowers them to change their relationship patterns in a positive way (Cohen et al., 2009).

Third, teachers and staff should first examine their values and beliefs regarding diversity as well as their knowledge of ASD. Teachers’ belief in the value of diversity is important because it moderates the association between intergroup friendship and intentions for social exclusion (Grütter & Meyer, 2014). By advancing teacher training and encouraging more positive interactions with autistic students, teachers could enhance their understanding, foster more positive attitudes toward autistic students, and address issues related to the bullying of autistic students (Cook et al., 2020; Gómez-Marí et al., 2021; Mavropoulou & Sideridis, 2014). Additionally, increased school exposure and personal contact are also positively associated with students’ positive attitudes toward ASD and prosocial emotions toward bullying (Cook et al., 2020).

Finally, parents’ role in bullying intervention should not be overlooked, and we advocate for an enhancement in understanding and support for them. The stress and mental health problems experienced by parents are important predictive factors for their children’s bullying victimization (Cappadocia et al., 2012; Holden et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2015). Besides their direct impact, parental stress and psychological issues may also indirectly influence children’s bullying victimization behavior through their effects on the quality of parent–child relationships, parenting skills, and attachment (Nocentini et al., 2019). Parents of children with ASD may be subjected to overtly hostile stares from others, criticism, and rude comments because of their children’s challenging behaviors, leading to rejection by friends and family (Salleh et al., 2020). Support from family, significant others, friends, or professionals can protect parents from affiliate stigma and enhance their psychological well-being (Mak & Kwok, 2010).

Limitations and Future Directions

Studies on bullying victimization among autistic students are rapidly expanding (Morton, 2021). Through a systematic review of empirical research, we have identified certain limitations in current research and areas that warrant further exploration and effort.

First, individuals diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome report more instances of bullying compared with those with typical autism (Zablotsky et al., 2014) as indicated by studies that adopted the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, which presents examples in which fewer social difficulties lead to more bullying. Although Asperger’s syndrome and autism are generally categorized within ASD, researchers exploring bullying dynamics should consider this information as crucial given the considerable heterogeneity within ASD. Factors that influence bullying victimization among students diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome and autism may significantly differ. Recent studies have made preliminary observations on these phenomena and provided corresponding explanations and speculations, yet more comprehensive investigations are imperative.

Second, although research on individual factors has occupied a substantial amount of space, it should be noted that an increasing number of studies have begun placing individual factors in a relatively secondary position when examining the negative social experiences of autistic individuals. For example, Morrison et al. (2019) found that variability in first impressions of autistic adults made by neurotypical raters is driven more by the characteristics of the rater (knowledge of autism and contact with autistic people) than by the characteristics of autistic individuals. Another study by Li et al. (2024) showed that autistic traits and barriers in the social and physical environment were the strongest predictors of school participation among autistic youths. However, autistic traits were not significant predictors when all other factors were controlled for, leading to the conclusion that the barriers to school participation of autistic young people may primarily stem from factors within the school environment (Li et al., 2024). In our systematic review, we found that there are inconsistencies in the findings of previous research related to individual factors (e.g., contradictions in bullying prevalence based on gender, age, race, social difficulties, etc.) and observed a greater consensus in findings related to contextual factors. These findings suggest the need for future research to focus more on contextual factors. In particular, in studies of bullying, taking contextual factors into account can help researchers avoid over-attributing traits of autistic individuals and prevent arriving at victim-blaming conclusions. Additionally, we believe that a substantial potential exists for a further exploration of contextual factors. Studies until now have incorporated an array of microlevel variables. Compared with research on bullying in the general population, studies have clearly overlooked the role of teachers and the community. The sole study focusing on teachers indicated that teacher-led initiatives for altering attitudes toward ASD were beneficial in reducing bullying victimization among autistic students (Falkmer et al., 2012). However, the specific nature of such initiatives and the extent to which other students’ attitudes were altered remain unknown.

For the peer groups, there is a need for further studies on moral identity development, explanations for social transgressions at different developmental stages, and how these societal conventions and norms impact autistic students’ experiences in school. Based on social domain theory, Bottema-Beutel et al. (2017) found that as children grow older, their perceptions of the failure to include autistic peers shift from providing only moral justifications to becoming more complex (justifications from the moral, personal, societal, and prudential domains). The complexity may result in an evaluation shift from viewing acts that violate moral prescriptions as impermissible to determining that these violations are permissible under certain circumstances (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2017). Processes of moral disengagement may play a significant role in the development of bullying (Hymel & Bonanno, 2014). Gaining a clear understanding of how typically developing children reason about bullying toward autistic students will be a valuable future direction for research, with implications for educational practice.

Finally, more longitudinal studies are necessary. For instance, the reciprocal effects model assumes feelings of loneliness and social isolation to be direct consequences of bullying (Humphrey & Symes, 2011), but an empirical study identified them as antecedents to bullying (Junttila et al., 2023; Storch et al., 2012). This issue is particularly pronounced with regard to psychiatric co-occurring conditions and internalization problems. In a recent long-term study, Rodriguez et al. (2021) found that early bullying victimization may influence later internalized symptoms, while the adverse path is not significant.

Conclusion

The general goal of our review was to examine factors of bullying victimization among autistic students and further elucidate several unresolved issues identified in previous reviews. By adopting social identity theory (stigma-based bullying framework), attribution theory, and the REPIM framework, we attempted to understand the role of autistic traits and behavioral difficulties in the dynamics of bullying victimization among autistic students. In this process, we highlighted the crucial role of a perspective integrating both individual and context factors. Simply put, it is equally important to consider how others in the situation interpret and respond emotionally and behaviorally to differences among autistic students. Additionally, to address the inconsistent findings regarding the relation between social difficulties and victimization in other studies, we summarized and discussed recent results. Most studies found that social difficulties can positively predict an increase in bullying incidents. However, students with higher levels of social difficulties may be unable to perceive or report bullying, highlighting the need to consider multiple informants and proper measurements in subsequent research.

Regarding contextual factors, the reviewed studies have focused on three main stakeholders: schools, parents, and peers. Fostering a secure, inclusive, and supportive school climate; having mentally healthy, confident, and proactive parents; and cultivating meaningful friendships are crucial for autistic students. Although a significant amount of research has examined teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and relationships with autistic students, fewer studies have directly linked these variables to bullying victimization. Future research could further explore the role of teachers and the interactive dynamics between different entities in bullying victimization, such as teacher–student and teacher–parent relationships. In addition, this will provide significant insights into the development of a comprehensive multilevel strategy for bullying prevention and intervention for autistic students.

Notes

DSM-5 has grouped Asperger’s syndrome into Autistic Spectrum Disorders due to overlapping features and diagnostic inconsistencies. However, Asperger’s syndrome remains a well-defined clinical entity with distinct semiology and characteristic clinical presentations. All over the world, teams working on Asperger’s syndrome continue to use this diagnosis to indicate a subtype of ASD with no language delay and a normal or superior IQ (Mirkovic & Gérardin 2019).

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. (1991). Child behavior checklist. Burlington (Vt), 7, 371–392.

Adams, R. E., Fredstrom, B. K., Duncan, A. W., Holleb, L. J., & Bishop, S. L. (2014). Using self- and parent-reports to test the association between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms in verbally fluent adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(4), 861–872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1938-0

Adams, R. E., Taylor, J. L., & Bishop, S. L. (2020). Brief report: ASD-related behavior problems and negative peer experiences among adolescents with ASD in general education settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4548–4552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04508-1

Ashburner, J., Saggers, B., Campbell, M. A., Dillon-Wallace, J. A., Hwang, Y.-S., Carrington, S., & Bobir, N. (2019). How are students on the autism spectrum affected by bullying? Perspectives of students and parents. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 19(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12421

Association, A. P. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Bear, G. G., Yang, C., Pell, M., & Gaskins, C. (2014). Validation of a brief measure of teachers’ perceptions of school climate: Relations to student achievement and suspensions. Learning Environments Research, 17(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-014-9162-1

Begeer, S., Fink, E., van der Meijden, S., Goossens, F., & Olthof, T. (2016). Bullying-related behaviour in a mainstream high school versus a high school for autism: Self-report and peer-report. Autism, 20(5), 562–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315597525

Bottema-Beutel, K., Turiel, E., DeWitt, M. N., & Wolfberg, P. J. (2017). To include or not to include: Evaluations and reasoning about the failure to include peers with autism spectrum disorder in elementary students. Autism, 21(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315622412

Bowes, L., Maughan, B., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2010). Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: Evidence of an environmental effect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(7), 809–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02216.x

Bronfenbrenner, U. (Ed.). (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage Publications Ltd.

Cappadocia, M. C., Weiss, J. A., & Pepler, D. (2012). Bullying experiences among children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1241-x

Carrington, S., Campbell, M., Saggers, B., Ashburner, J., Vicig, F., Dillon-Wallace, J., & Hwang, Y.-S. (2017). Recommendations of school students with autism spectrum disorder and their parents in regard to bullying and cyberbullying prevention and intervention. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(10), 1045–1064. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1331381

Casanova, M. F., Frye, R. E., Gillberg, C., & Casanova, E. L. (2020). Editorial: Comorbidity and autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 617395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.617395

Chou, W. J., Hsiao, R. C., Ni, H. C., Liang, S. H., Lin, C. F., Chan, H. L., Hsieh, Y. H., Wang, L. J., Lee, M. J., Hu, H. F., & Yen, C. F. (2019). Self-reported and parent-reported school bullying in adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorder: the roles of autistic social impairment, attention-deficit/hyperactivity and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071117

Cohen, J., Fege, A., & Pickeral, T. (2009). Measuring and improving school climate: A strategy that recognizes, honors and promotes social, emotional and civic learning the foundation for love, work and engaged citizenry. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 111(1), 180–213.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2005). Social responsiveness scale (SRS). Western Psychological Services.

Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). Social responsiveness scale-second edition (SRS-2). Western Psychological Services.

Cook, A., Ogden, J., & Winstone, N. (2016). The experiences of learning, friendship and bullying of boys with autism in mainstream and special settings: A qualitative study. British Journal of Special Education, 43(3), 250–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12143

Cook, A., Ogden, J., & Winstone, N. (2020). The effect of school exposure and personal contact on attitudes towards bullying and autism in schools: A cohort study with a control group. Autism, 24(8), 2178–2189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320937088

Dake, J. A., Price, J. H., & Telljohann, S. K. (2003). The nature and extent of bullying at school. Journal of School Health, 73(5), 173–180.

Earnshaw, V. A., Reisner, S. L., Menino, D., Poteat, V. P., Bogart, L. M., Barnes, T. N., & Schuster, M. A. (2018). Stigma-based bullying interventions: A systematic review. Developmental Review, 48, 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.001

Falkmer, M., Parsons, R., & Granlund, M. (2012). Looking through the Same eyes? Do teachers’ participation ratings match with ratings of students with autism spectrum conditions in mainstream schools? Autism Research and Treatment, 2012, 656981. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/656981

Ferrigno, S., Cicinelli, G., & Keller, R. (2022). Bullying in autism spectrum disorder: prevalence and consequences in adulthood. Journal of Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.36148/2284-0249-466

Fink, E., Olthof, T., Goossens, F., van der Meijden, S., & Begeer, S. (2018). Bullying-related behaviour in adolescents with autism: Links with autism severity and emotional and behavioural problems. Autism, 22(6), 684–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316686760

Finke, E. H., & Dunn, D. H. (2023). Neurodiversity and double empathy: can empathy disconnects be mitigated to support autistic belonging? Disability & Society, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2023.2295802

Forrest, D. L., Kroeger, R. A., & Stroope, S. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder symptoms and bullying victimization among children with autism in the United States. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 560–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04282-9

Ghaziuddin, M. (2008). Defining the behavioral phenotype of Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(1), 138–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0371-7

Gillespie-Smith, K., Mair, A. P. A., Alabtullatif, A., Pain, H., & McConachie, D. (2024). A spectrum of understanding: A qualitative exploration of autistic adults’ understandings and perceptions of friendship (s). Autism in Adulthood. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2023.0051

Gómez-Marí, I., Sanz-Cervera, P., & Tárraga-Mínguez, R. (2021). Teachers’ knowledge regarding autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A systematic review. Sustainability, 13(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095097

Greenlee, J. L., Winter, M. A., & Marcovici, I. A. (2020). Brief report: Gender differences in experiences of peer victimization among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3790–3799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04437-z

Grütter, J., & Meyer, B. (2014). Intergroup friendship and children’s intentions for social exclusion in integrative classrooms: The moderating role of teachers’ diversity beliefs. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44(7), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12240

Hebron, J., & Humphrey, N. (2014). Exposure to bullying among students with autism spectrum conditions: A multi-informant analysis of risk and protective factors. Autism, 18(6), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313495965

Hebron, J., Humphrey, N., & Oldfield, J. (2015). Vulnerability to bullying of children with autism spectrum conditions in mainstream education: A multi-informant qualitative exploration. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 15(3), 185–193.

Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 575–604. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109

Holden, R., Mueller, J., McGowan, J., Sanyal, J., Kikoler, M., Simonoff, E., Velupillai, S., & Downs, J. (2020). Investigating bullying as a predictor of suicidality in a clinical sample of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 13(6), 988–997. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2292

Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(4), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

Hsiao, M. N., Tai, Y. M., Wu, Y. Y., Tsai, W. C., Chiu, Y. N., & Gau, S. S. (2022). Psychopathologies mediate the link between autism spectrum disorder and bullying involvement: A follow-up study. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 121(9), 1739–1747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2021.12.030

Humphrey, N., & Hebron, J. (2015). Bullying of children and adolescents with autism spectrum conditions: A ‘state of the field’ review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(8), 845–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2014.981602

Humphrey, N., & Symes, W. (2010). Responses to bullying and use of social support among pupils with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) in mainstream schools: A qualitative study. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01146.x

Humphrey, N., & Symes, W. (2011). Peer interaction patterns among adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) in mainstream school settings. Autism, 15(4), 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310387804

Hunsche, M. C., Cervin, M., Storch, E. A., Kendall, P. C., Wood, J. J., & Kerns, C. M. (2022). Social functioning and the presentation of anxiety in children on the autism spectrum: A multimethod, multiinformant analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 131(2), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000724

Hwang, S., Kim, Y. S., Koh, Y. J., & Leventhal, B. L. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder and school bullying: Who is the victim? Who is the perpetrator? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3285-z

Hymel, S., & Bonanno, R. A. (2014). Moral disengagement processes in bullying. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 278–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947219

Imuta, K., Song, S., Henry, J. D., Ruffman, T., Peterson, C., & Slaughter, V. (2022). A meta-analytic review on the social–emotional intelligence correlates of the six bullying roles: Bullies, followers, victims, bully-victims, defenders, and outsiders. Psychological Bulletin, 148(3–4), 199.

Junttila, M., Kielinen, M., Jussila, K., Joskitt, L., Mantymaa, M., Ebeling, H., & Mattila, M. L. (2023). The traits of autism spectrum disorder and bullying victimization in an epidemiological population. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02228-2

Kaland, N. (2011). Brief report: Should Asperger syndrome be excluded from the forthcoming DSM-V? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(3), 984–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.011

Kennedy, D. P., & Adolphs, R. (2012). Perception of emotions from facial expressions in high-functioning adults with autism. Neuropsychologia, 50(14), 3313–3319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.09.038

Kloosterman, P. H., Kelley, E. A., Parker, J. D., & Craig, W. M. (2014). Executive functioning as a predictor of peer victimization in adolescents with and without an autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(3), 244–254.

Kmet, L. M. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Edmonton.

Li, B., Heyne, D., Scheeren, A., Blijd-Hoogewys, E., & Rieffe, C. (2024). School participation of autistic youths: The influence of youth, family and school factors. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613231225490

Liu, T. L., Wang, P. W., Yang, Y. C., Shyi, G. C., & Yen, C. F. (2019). Association between facial emotion recognition and bullying involvement among adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245125

Liu, T. L., Hsiao, R. C., Chou, W. J., & Yen, C. F. (2021). Social anxiety in victimization and perpetration of cyberbullying and traditional bullying in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115728

Maïano, C., Normand, C. L., Salvas, M. C., Moullec, G., & Aimé, A. (2016). Prevalence of school bullying among youth with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Research, 9(6), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1568

Mak, W. W. S., & Kwok, Y. T. Y. (2010). Internalization of stigma for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in Hong Kong. Social Science and Medicine, 70(12), 2045–2051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.023

Matson, J. L., & Goldin, R. L. (2013). Comorbidity and autism: Trends, topics and future directions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(10), 1228–1233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.07.003

Matthias, C., LaVelle, J. M., Johnson, D. R., Wu, Y. C., & Thurlow, M. L. (2021). Exploring predictors of bullying and victimization of students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Findings from NLTS 2012. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(12), 4632–4643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04907-y

Mavropoulou, S., & Sideridis, G. D. (2014). Knowledge of autism and attitudes of children towards their partially integrated peers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(8), 1867–1885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2059-0

Milton, D. E. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem.’ Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Mirkovic, B., & Gérardin, P. (2019). Asperger’s syndrome: What to consider? L’encephale, 45(2), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2018.11.005

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., ... Prisma-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4, 1-9.

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60.

Morrison, K. E., DeBrabander, K. M., Faso, D. J., & Sasson, N. J. (2019). Variability in first impressions of autistic adults made by neurotypical raters is driven more by characteristics of the rater than by characteristics of autistic adults. Autism, 23(7), 1817–1829. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318824104

Morton, H. E. (2021). Assessment of bullying in autism spectrum disorder: systematic review of methodologies and participant characteristics. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8(4), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00232-9

Muratori, F., Turi, M., Prosperi, M., Narzisi, A., Valeri, G., Guerrera, S., ... Vicari, S. (2019). Parental perspectives on psychiatric comorbidity in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders receiving publicly funded mental health services. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 107.

Nocentini, A., Fiorentini, G., Di Paola, L., & Menesini, E. (2019). Parents, family characteristics and bullying behavior: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.010

Norberg, M. M., Kavanagh, D. J., Olivier, J., & Lyras, S. (2016). Craving cannabis: A meta-analysis of self-report and psychophysiological cue—reactivity studies. Addiction, 111(11), 1923–1934. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13472

Oexle, N., & Corrigan, P. W. (2018). Understanding mental illness stigma toward persons with multiple stigmatized conditions: Implications of intersectionality theory. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 69(5), 587–589. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700312

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001

Park, I., Gong, J., Lyons, G. L., Hirota, T., Takahashi, M., Kim, B., Lee, S. Y., Kim, Y. S., Lee, J., & Leventhal, B. L. (2020). Prevalence of and factors associated with school bullying in students with autism spectrum disorder: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Yonsei Medical Journal, 61(11), 909–922. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2020.61.11.909

Perry, E., Mandy, W., Hull, L., & Cage, E. (2022). Understanding camouflaging as a response to autism-related stigma: A social identity theory approach. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(2), 800–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04987-w

Rieffe, C., Camodeca, M., Pouw, L. B. C., Lange, A. M. C., & Stockmann, L. (2012). Don’t anger me! Bullying, victimization, and emotion dysregulation in young adolescents with ASD. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(3), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.680302

Rodriguez, G., Drastal, K., & Hartley, S. L. (2021). Cross-lagged model of bullying victimization and mental health problems in children with autism in middle to older childhood. Autism, 25(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320947513

Rowley, E., Chandler, S., Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Loucas, T., & Charman, T. (2012). The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with an autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1126–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.03.004

Rudolph, K. D., Monti, J. D., Modi, H., Sze, W. Y., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2020). Protecting youth against the adverse effects of peer victimization: Why do parents matter? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48, 163–176.

Salleh, N. S., Abdullah, K. L., Yoong, T. L., Jayanath, S., & Husain, M. (2020). Parents’ experiences of affiliate stigma when caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 55, 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.09.002

Schacter, H. L., Lessard, L. M., Kiperman, S., Bakth, F., Ehrhardt, A., & Uganski, J. (2021). Can friendships protect against the health consequences of peer victimization in adolescence? A systematic review. School Mental Health, 13(3), 578–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09417-x

Schokman, C., Downey, L. A., Lomas, J., Wellham, D., Wheaton, A., Simmons, N., & Stough, C. (2014). Emotional intelligence, victimisation, bullying behaviours and attitudes. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.10.013

Schroeder, J. H., Cappadocia, M. C., Bebko, J. M., Pepler, D. J., & Weiss, J. A. (2014). Shedding light on a pervasive problem: A review of research on bullying experiences among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1520–1534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-2011-8

Schrooten, I., Scholte, R. H. J., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Hymel, S. (2018). Participant roles in bullying among Dutch adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(6), 874–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1138411

Shiva Kumar, A. K., Stern, V., Subrahmanian, R., Sherr, L., Burton, P., Guerra, N., Muggah, R., Samms-Vaughan, M., Watts, C., & Mehta, S. K. (2017). Ending violence in childhood: A global imperative. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(sup1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1287409

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge University Press.

Smith, P. K. (2016). Bullying: Definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 519–532.

Sofronoff, K., Dark, E., & Stone, V. (2011). Social vulnerability and bullying in children with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 15(3), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310365070

Sreckovic, M. A., Brunsting, N. C., & Able, H. (2014). Victimization of students with autism spectrum disorder: A review of prevalence and risk factors. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1155–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.004