Abstract

Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy has been widely used to treat colorectal cancer. Here, we report a case of a 71-year-old man, former smoker (40 pack-years), with no history of relevant exposures such as occupational, environmental or drug exposure. The patient developed acute partial respiratory insufficiency concomitant with the eighth cycle of adjuvant chemotherapy with oxaliplatin and capecitabine for stage IIIA colorectal adenocarcinoma. After the exclusion of other causes, namely pulmonary thromboembolism, high-resolution chest computed tomography (CT) showed a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern. After the discussion at the multidisciplinary meeting on interstitial lung diseases and considering the temporal association between clinical and imaging findings and chemotherapy treatment, along with exclusion of other potential causes, the most likely hypothesis was pulmonary fibrosis secondary to oxaliplatin. A literature review on this scope was also performed. We conclude that pulmonary fibrosis is a rare complication of oxaliplatin, but with the widespread use of oxaliplatin combinations in colorectal cancer, active assessment for interstitial lung disease is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Oxaliplatin and capecitabine combination has become a well-established cancer treatment. |

When used as monotherapy or adjuvant to surgery, several toxicities have been reported. |

Acute pulmonary toxicity is a very rare side effect, and the true incidence is unknown. |

Data on oxaliplatin-induced acute pulmonary toxicity were reviewed and a case presented. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12827312.

Introduction

The introduction of oxaliplatin, a third-generation platinum drug, as part of treatment in metastatic colorectal carcinoma occurred about 20 years ago in metastatic and adjuvant settings [1,2,3]. In addition, the combination of oxaliplatin and capecitabine has become a well-established treatment as monotherapy or as an adjuvant to surgery [1,2,3].

The main toxicities of oxaliplatin reported in phase 3 randomized controlled trials were haematological, gastrointestinal and, less frequently, neurological toxicities [4,5,6,7].

Oxaliplatin-induced acute pulmonary toxicity is a very rare side effect and is usually a diagnosis of exclusion. Although the true incidence is unknown, it has been associated with respiratory failure and pulmonary infiltrates, with subsequent progression to fibrosis. In addition, and given its rarity, there are no established guidelines for its management. Thus, the present case report and literature review aims to put into evidence the acute pulmonary toxicity induced by oxaliplatin that was resolved with drug discontinuation, given its rarity and potential severity.

Case Presentation

Here, we report the case of a 71-year-old man, former smoker (40 pack-years), with severe obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA; treated with continuous positive airway pressure, CPAP) under surveillance at the Pulmonology Outpatient Clinic since 2014. On further enquiry, he had no history of tuberculosis and no relevant occupational or environmental exposure.

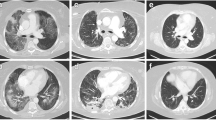

Adjuvant chemotherapy with XELOX (oxaliplatin intravenous, 130 mg/m2 and capecitabine 2.000 mg/m2) was offered in 3-week treatment cycles, since March 2016, following sigmoidectomy and ileostomy for stage IIIA rectal adenocarcinoma. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan performed for disease staging revealed emphysema at upper lobes, with no other relevant findings (Fig. 1). Pulmonary function tests and blood gas exchange performed at that time were normal.

In October 2016, 1 week after the eighth cycle of chemotherapy, he rapidly developed progressive dyspnoea grade 4 [Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scale] and productive cough without fever. He was admitted to the emergency department with evidence of hypoxic respiratory failure (blood gas analysis: pH: 7.45, pCO2: 32 mmHg, pO2: 53 mmHg, HCO3: 22 mEq/L, sO2: 89% with FiO2: 21%). A full blood count was performed, revealing mild anemia (haemoglobin: 116 g/L), with normal white blood cell count (6.0 × 109/L) and eosinophil count (0.2 × 109/L). The C-reactive protein (CRP) level was low (1.71 mg/dL), D-dimer test was negative and there were no biochemical signs of other organ failure (serum creatinine: 1.2 mg/dL). Chest X-ray showed fine reticular opacities consistent with an interstitial pattern without pulmonary infiltrates suggestive of pneumonia (Fig. 1). He was treated on an outpatient basis with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and clarithromycin, but his breathlessness deteriorated despite this course of antibiotic therapy, being evaluated in November at the Pulmonology Outpatient Clinic. At that time, no infectious causes that triggered the clinical picture were identified, and lymphangitis was considered less likely because the disease was stable, without evidence of recurrence.

A ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy was performed, without signs of pulmonary thromboembolism, and an echocardiogram was normal. Pulmonary function test showed a mild restrictive pattern [forced vital capacity (FVC) = 2.47 mL/78.9%, total lung capacity (TLC) = 4.69 mL/78.9%] and severe impairment of diffusion to carbon monoxide (DLCOc = 35.4%).

The patient had progressive improvement under home oxygen therapy, with an overall clinical and gas exchange improvement and a clear reduction in dyspnoea grade (mMRC 2). A high-resolution CT (HRCT) chest scan performed in December revealed bilateral peripheral septal thickening, honeycombing and bronchiectasis, suggestive of a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern (Fig. 2).

The case was discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting on interstitial lung diseases (ILD). Considering the temporal association between clinical and imaging findings and chemotherapy treatment, the most likely hypothesis was pulmonary fibrosis secondary to oxaliplatin. Thus, we opted for treatment discontinuation, a decision also discussed with his oncologist.

In March 2017, there was evidence of complete resolution of hypoxemic respiratory failure (pH: 7.44, pCO2: 40.6 mmHg, pO2: 78 mmHg, HCO3: 27.2 mEq/L, sO2: 96% with FiO2: 21%), and the patient’s clinical situation remained stable. He currently continues follow-up at the Oncology Department, with evidence of cancer remission, and at the Pulmonology Outpatient Clinic, with clinical and radiological aspects unchanged.

Written informed consent to publish the patient’s case was provided by the patient in an anonymous form.

Discussion

Oxaliplatin-induced grade IV pulmonary toxicity and pulmonary fibrosis are rare, reported in less than 1% of patients, and one patient death from eosinophilic pneumonia has been recorded [6]. Twenty-six cases of oxaliplatin-related pulmonary toxicity have been described in the literature, as shown in Table 1. Currently, the available data on its pulmonary toxicity are scarce, and there are no established recommendations for its management.

Drug-induced pneumonitis is usually a diagnosis of exclusion. It is established by a temporal association between exposure to a specific drug and the development of respiratory symptoms and signs, supported by radiological findings or a pathological pattern. In a cancer patient under chemotherapy, it must be considered when diagnostic algorithms have excluded all other potential causes, such as infection, pulmonary embolism, alveolar haemorrhage, lymphangiosis and heart failure [5,6,7]. The diagnostic suspicion is crucial, because drug withdrawal often results in clinical and radiological improvement, as observed in the case we report [5]. The temporal evolution after the beginning of treatment varies between studies. Thus, interstitial pneumonia may occur soon after treatment initiation. It may also occur a few months after adjuvant treatment, as seen in our patient.

Wilcox et al. reported three cases of pre-existing mild ILD worsening under oxaliplatin therapy, in one of the cases with severe acute respiratory failure and death [8].

An accurate diagnosis of pulmonary toxicity is challenging given the non-specificity of symptoms and variety of other probable causes, making accurate diagnosis difficult.

Most cases of oxaliplatin-associated pulmonary fibrosis reported in the literature have a rapid and fatal course [9,10,11]. Pontes et al. described three fatal cases of interstitial pneumonitis rapidly evolving to pulmonary fibrosis and death after oxaliplatin administration, as part of an oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin regimen, without response to conventional medical treatment [12]. Our case, similarly to others mentioned above, puts into evidence the potential pulmonary toxicity of this drug, fortunately with a good clinical evolution under chemotherapy discontinuation. The interstitial pattern seemed to be rapidly progressive, evolving to fibrosis, as observed in the HRCT scan of December 2016.

Only a few publications have described pulmonary fibrosis following oxaliplatin. More recently, Lee et al. described a case of organizing pneumonia secondary to chemotherapy combined with oxaliplatin [5], and Wildner et al. reported acute lung injury after one cycle of combined chemotherapy with 5-FU and oxaliplatin, with histological evidence of extensive granulomatous inflammation [13]. A case of eosinophilic pneumonia secondary to oxaliplatin monotherapy with a fatal course was also reported [6]. Overall, 30 cases of oxaliplatin-related pulmonary toxicity have been reported in the literature, as shown in Table 1, of which more than 50% had an adverse outcome (17 patients died).

Most patients were male (23/30, 77%), 83% were older than 60 years and diagnosed with metastatic colorectal carcinoma, and 57% were treated with oxaliplatin for less than 6 months. As shown in Table 1, 12 (40%) patients had previous lung disease and three (10%) were smokers. In the current report, our patient had lung emphysema and was a former smoker. Indeed, it has been suggested that previous lung disease may be a risk factor for oxaliplatin-induced pulmonary toxicity [8], but considering the small number of cases reported, this correlation cannot be assumed. Of the 30 cases reported, nine patients died as a result of pulmonary toxicity.

Thus, as mentioned above, drug-induced pneumonitis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Indeed, extensive research has been performed to rule out the most common causes of pneumonitis, including in the patient we describe here. Fifteen of the 26 patients were treated according to the FOLFOX protocol (oxaliplatin/5-FU/leucovorin), and five of the 26 patients were treated with the FOLFOX protocol with the addition of bevacizumab, a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor monoclonal antibody. Few incidents of acute lung fibrosis have been reported in patients treated with 5-FU and cisplatin, although 5-FU is a widely used agent.

Muneoka et al. [14] reported a case of interstitial pneumonitis induced by oxaliplatin, 5-FU and leucovorin, which improved with therapy, without additional pulmonary toxicity following the introduction of 5-FU/leucovorin alone. The main cause of induced interstitial pneumonitis in the cases reported in the literature is thought to be oxaliplatin [15].

The exact mechanisms that link oxaliplatin to direct lung parenchyma damage are not known. One of the conclusions of a study by Rubbia-Brandt et al. [16], following examination of liver specimens from patients with colorectal carcinoma undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy and metastasectomy, was that oxaliplatin can favor sinusoidal injury, fibrosis and veno-occlusive lesions. These effects may be related to oxidative damage and glutathione depletion triggered by oxaliplatin and may be extrapolated as a possible pathological mechanism of pulmonary injury [16]. In fact, glutathione protects lung parenchyma from oxidative damage, and therefore its depletion may trigger interstitial pneumonitis and subsequent pulmonary fibrosis [16].

Conclusions

Overall, oxaliplatin is a widely used drug in colorectal cancer treatment and other malignancies; however, it is important to be aware of its rare, but potentially fatal, side effects. From the data presented here, it is clearly evident that further investigation is still needed to eventually modify the current clinical practice in this regard, considering the possible severity of oxaliplatin-induced pulmonary toxicity for early detection and treatment of this complication. The pre-existence of fibrosis or any other underlying disease will further aggravate such condition; therefore, great caution and close clinical and imaging follow-up should be ensured when oxaliplatin treatment is indicated for these patients.

References

André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–51.

André T, Tournigand C, Achille E, Tubiana-Mathieu N, Lledo G, Raoul Y, et al. Adjuvant treatment of colon cancer MOSAIC study’s main results. Bull Cancer. 2006;93:S5–9.

de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, et al. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938–47.

Yagüe X, Soy E, Merino B, Puig J, Fabregat M, Colomer R. Interstitial pneumonitis after oxaliplatin treatment in colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2005;7:515–7.

Lee E, Lee S, In K, Kim C, Park S. Organizing pneumonia associated with oxaliplatin-combined chemotherapy: a case report. Med Princ Pract. 2012;21:89–92.

Ramanathan R, Clark J, Kemeny N, Lenz H, Gococo K, Haller D, et al. Safety and toxicity analysis of oxaliplatin combined with fluorouracil or as a single agent in patients with previously treated advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2904–11.

Ryu C, Jung E, Kim G, Kim S, Hwang D. Oxaliplatin-induced pulmonary fibrosis: two case reports. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27:266–9.

Wilcox B, Ryu J, Kalra S. Exacerbation of pre-existing interstitial lung disease after oxaliplatin therapy: a report of three cases. Respir Med. 2008;102:273–9.

Garrido M, O’Brien A, González S, Clavero J, Orellana E. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis during oxaliplatin chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: case report. Chest. 2007;132:1997–9.

Gagnadoux F, Roiron C, Carrie E, Monnier-Cholley L, Lebeau B. Eosinophilic lung disease under chemotherapy with oxaliplatin for colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:388–90.

Arévalo Lobera S, Sagastibeltza Mariñelarena N, Elejoste Echeberría I, Melé Olivé M, Egaña Otaño L, Basterretxea Badiola L, et al. Fatal pneumonitis induced by oxaliplatin. Clin Transl Oncol. 2008;10:764–7.

Pontes L, Armentano D, Soares A, Gansl R. Fatal pneumonitis induced by oxaliplatin: description of three cases. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5:104–9.

Wildner D, Boxberger F, Wein A, Wolff K, Albrecht H, Männlein G, et al. Granulomatous lung disease requiring mechanical ventilation induced by a single application of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: a case report. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:683948.

Muneoka K, Shirai Y, Sasaki M, Wakai T, Sakata J, Hatakeyama K. Interstitial pneumonia arising in a patient treated with oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX). Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:457–9.

Pasetto L, Monfardini S. Is acute dyspnea related to oxaliplatin administration? World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2006;12:5907–8.

Rubbia-Brandt L, Audard V, Sartoretti P, Roth A, Brezault C, Le Charpentier M, et al. Severe hepatic sinusoidal obstruction associated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:460–6.

Trisolini R, Lazzari Agli L, Tassinari D, Rondelli D, Cancellieri A, Patelli M, et al. Acute lung injury associated with 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatinum combined chemotherapy. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:243–5.

Jung K, Kil S, Choi I, Seo J, Shin C, Kim Y, et al. Interstitial lung diseases in patients treated with oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFOX). Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1181–2.

Ruiz-Casado A, García M, Racionero M. Pulmonary toxicity of 5-fluoracil and oxaliplatin. Clin Transl Oncol. 2006;8:624.

Pena Alvarez C, Suh Oh H, Sáenz de Miera Rodríguez A, García Arroyo F, Covela Rúa M, Salgado Boquete L, et al. Interstitial lung disease associated with oxaliplatin: description of two cases. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:332–3.

Mundt P, Mochmann H, Ebhardt H, Zeitz M, Duchmann R, Pauschinger M. Pulmonary fibrosis after chemotherapy with oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil for colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2007;73:270–2.

Shah A, Udwadia ZF, Almel S. Oxaliplatin-induced lung fibrosis. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2009;30:116–8.

Fekrazad M, Eberhardt S, Jones D, Lee F. Development of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia with platinum-based chemotherapy for metastatic rectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2010;9:177–8.

Lai J, Wang W, Lai Y, Lin P, Chang S. Acute interstitial pneumonitis in a patient receiving a FOLFOX-4 regimen plus cetuximab treated with pulse therapy. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:425–8.

Moskovitz M, Wollner M, Haim N. Oxaliplatin-induced pulmonary toxicity in gastrointestinal malignancies: two case reports and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2015;2015:341064.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient whose case is described here. N. Martins would like to thank the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT–Portugal) for the Strategic project ref. UID/BIM/04293/2013 and “NORTE2020–Programa Operacional Regional do Norte” (NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000012).

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Ana C. Moreira, João Portela, Carlos Couto, José Duarte, Natália Martins, and Jorge Soares have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Written informed consent to publish the patient’s case was provided by the patient in an anonymous form.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12827312.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moreira, A.C., Portela, J., Couto, C. et al. Pulmonary Fibrosis Secondary to Oxaliplatin Treatment: From Rarity to Reality: A Case Study and Literature Review. Oncol Ther 8, 183–190 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-020-00127-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-020-00127-z