Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review endeavors to highlight the structural, systematic and societal challenges that female researchers encounter. It also acknowledges the achievements and initiatives that women scientists had throughout the HIV history, which have brought visibility to issues within the field and provided solutions.

Recent Findings

Key innovations in the field include the implementation of gender quotas in executive roles, editorial positions and among journal authors. Additionally, the establishment of gender workshops and mentorship programs aimed at young female researchers.

Summary

Despite the increasing number of female doctors in recent decades, women continue to be underrepresented in academic, scientific, clinical and leadership positions. Exposing the bullying and sexism that takes places within it, which perpetuate the exclusion of female doctors. A comprehensive understanding of these barriers that affect women physicians, remain critical to improve the equity within the medical field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When discussing about HIV, we involve medical care, science, health, policies, activism, sexual health, human rights, ageing, prevention, and in all of those matters, women are involved. Women living with HIV (WWH), women who are HIV providers and women engaged in science and research in the HIV field, all of them constitute an integral part of its history. There’s no HIV history without women. Nevertheless, women remain underrepresented in many areas in this field: as research participants in clinical trials, as leaders of HIV clinic/departments/research Labs and as scientists [1,2,3]. In 2021, women and girls accounted for 49% of all new HIV diagnoses and constituted 54% of the 38.4 million of people with HIV (PWH) worldwide [4]. Nonetheless, women still do not, perceive themselves at risk for acquiring HIV, and nor do physicians in many parts of the world [5,6,7].

This perspective extends to the realm of scientific inquiry. As mentioned, it is well documented, that women are underrepresented in research and leadership roles [8]. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, a member of the virologist team that isolated HIV retrovirus at Institute Pasteur 40 years ago and later won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Medicine, declared that she faced sexism in her journey; she was once told “Women had never accomplished anything in science (…) Forget your dreams, women should stay at home.”[9] Unfortunately, after many decades, women researchers and clinicians keep facing similar barriers within the medical field nowadays.

Although there has been an effort towards the visibility of this inequity of women in this field, and progress toward equality has accelerated in the last decade, especially in North America and Europe, where many women are attaining leadership positions and contributing to a rising number of scientific publications, their participation in these fields still lags behind men [10, 11]. This gap is even more important in regions such as African, Asian and Oceania countries where the representation of women in science falls below 30% [10, 12].

There remains a considerable journey ahead for research women to thrive within a scientific environment characterized by equality, equity and diversity, devoid of gender bias. In this review, we will emphasize the principal barriers that female physicians encounter, propose measures to broaden the scope of opportunities for aspiring young researchers, along with identifying the components of the system that must be held accountable and prompted to take appropriate remedial measures.

How Gender Disparity Persist

Sexism is Still in the Room

Hundred fifty-four years ago, Dr. Henry Bennet wrote a letter published in one of the most prestigious scientific journal “The Lancet”, in which he stated that women “are sexually, constitutionally and mentally burdened (…) by the heavy responsibilities of general medical and surgical practice” [13]. Since then, women had to dedicate time to produce scientific evidence, that they indeed possess the intellectual and physical capacities necessary to succeed in any domain, including in the health science. In the last decade, more than 3000 studies have been published about women inequity in this field, in which biases, gender stereotypes, and, of course, sexism continue to be the main impediments preventing women from obtaining and holding permanent or leadership position, not their capabilities.

Additionally, according to a recent English study, 61% of researchers had either experienced or witnessed bullying [14]. This “bullying tool”, along with sabotage and abuse of power, has been used to dissuade female researchers in places or positions where a man of lower, equal or higher rank feels intellectually threatened, being perpetuated by themselves [15, 16]. Mostly, this has been done by male principal investigators, against minorities and in particular women, who are the primary victims [17, 18]. These barriers affect women since the outset of their careers, persist through specialty years to senior and directive positions, making it more difficult to remain and later be promoted, compared to men [16, 19]. Moreover, the absence of effective regulations in many regions such as in Latin America, against harassment, exacerbates these challenges by failing to shield complainants while protecting perpetrators.

Fellowship or Motherhood?

The motherhood “penalty” is still a very high price that women doctors pay to achieve their academic aspirations. Research reveals that 57.6% of women delay motherhood primarily to avoid interference with their education [20]. There is a relationship between delayed childbirth and the likelihood of encountering infertility [21, 22]. A cross-sectional study conducted among 1,056 cis-gender female physicians findings revealed that 75.6% of these women, chose to postpone starting a family, with 36.8% subsequently experiencing infertility issues. Notably, those who deferred childbirth for a period exceeding five years exhibited a higher susceptibility to these problems. It is paramount to underscore that a 45.7% of the participants, expressed regret over not initiation childbearing earlier, indicating that they would have made different reproductive choices if the medical environment were not characterized by such severe judgment and social stereotypes [23].

Moreover, 90% of pregnant women in residency programs experienced discrimination, for taking their maternity leave or requesting part-time shifts, which is perceived as a lack of commitment to their fellowship [17, 22]. To the extent that the program directors, attendings and residents who have previously given birth recommend their fellows not to get pregnant during residency [10, 20, 22]. Furthermore, compared to their non-medical peers, pregnant medical professionals are twice as likely to have an abortion, are more likely to have a high-risk pregnancy and to experience postpartum depression [21, 22]. It is ironic that 70% of doctors are only able breastfeed their babies for six months, either due to the absence or poor maintenance of lactation rooms in their workplace, and the lack of understanding of their services to carry out this activity [17, 20].

This maternity wall persists as children grow older, with women often assuming primary responsibilities for familial and household duties [10, 21]. For example, meetings are often scheduled during school drop-off and pick-up hours, with a limited daycare low-cost options in case kids get sick or during attending conferences [24, 25]. Despite the perception that scientific or medical mothers struggle to complete their professional and research obligations, there is evidence that shown that they can be even more productive than their peers -men and women- who do not have children and develop excellent leadership skills [22].

When COVID-19 hit, 70% of those in the first line as health providers were women, but only 30% of the representation of COVID-19 committees, were occupied by female care givers and researchers [26]. Additionally, women had more in-home duties as caregivers due to lockdown measures, dedicating an additional 15 hours per week to such activities compared to their men peers [27]. Notably, female doctors experienced significant disparities in earnings and had greater delayed in promotions during and after the pandemic, compared to men [27, 28]. Men reported experien-cing decreases levels of stress when compared 2020 vs 2021, whereas women persisted in facing heightened stress due to the accumulation of clinical, research, teaching and household responsibilities extending into 2021 [29]. Finally, it is important to acknowledge the psychological impact of this historic event on the mental health of women physicians, whether or not they worked as front-line providers [28].

Research Women Against Scientific Underrepresentation

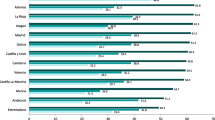

While women constitute 52.1% of college students and two-thirds of medical school enrollees, this percentage diminishes with the attainments of higher degrees [10, 30, 31]. It has been reported that women make up a smaller percentage of Full Professors in academia compared to men. In the Infectious diseases (ID) field, specifically in 2016, women represented 48.1% of Assistant Professors and only the 19.2% of Full Professors, in contrast to men [3]. Although the percentage of women holding Full Professor positions increased to 42.5% in 2020, they still constitute more than a half (66.8%) of the Assistant Professors [32].

Evidence has shown that women are less likely than men to receive promotions, even when they have equivalent institutional years, as well as same seniority and academic qualifications to compete for the position [17, 32]. A cross-sectional study demonstrated a delay in physicians women work promotions. Additionally, in this same study, it has been observed that the initial salaries of female doctor are notably lower than those of their male counterparts, across 93% of the 45 specialties and subspecialties examined. Furthermore, the annual pay increments for female doctors are modest, with an average increase of only 1.2%, in stark contrast to the more substantial 3.1% increases observed among male doctors [33]. The perpetuation of a system that disadvantages women in this sector stems from their exclusion from high academic ranks, which supports the absence of their contributions to decision-making processes on important boards, public policies and in international guidelines [3, 34].

It has been described that women are more likely to lack of taught by their mentors or authorities in terms of negotiation expertise. Such inadequate development in this skill is a significant factor contributing to the marginalization of women in science avoiding them to escalate into leadership positions throughout their careers [17, 35]. Consequently, when a woman acts and speak with determination and articulates her academic needs, she is perceived as a threat to the longstanding sexist structures [36]. The latter in combination, with the wage gap, excessive workloads professionally and personally, creates an environment for women of missed opportunities within academic institutions [17]. As a consequence of this phenomenon, it is not surprising that there is a lower number of grant applications submitted by women to NIH, compared to men [3]. Evidence indicates that in order to continue improving academically, good sponsorship is equally as crucial as good mentoring [32]. This lack of self-recognition is reflected in the fact that women are less likely to be nominated for important awards in their field, have fewer publications in elite journals, and therefore receive fewer citations and invitations to present conferences at international congress, compared to their male peers [3, 34, 35, 37].

It is not astonishing, since the system and society is an environment to propitiate women doubt about their own abilities, that the 75% of women have impostor syndrome, and have a sense of inadequacy [38]. The 90% of female surgeons in chief positions have impostor syndrome, compared of only 67.7% of men [39]. Though, the information of this regard is limited in the field of ID. In that sense, there is an urgent need of collectively focus more on the policies that truly changes to improve the academic field for women in science and medicine, and not in the urge to convince women that they need to fix themselves to fit in this men’s scientific world.

One consequential outcome of these dynamics is the underrepresentation of women among authors of scientific articles. A cross-sectional study published in The Lancet highlight disparities in ID authorship roles, revealing that while the proportion of male and female first authors is comparable (49.3% vs 50.7%), men significantly outnumber women in the last authors proportion (65.1%). Similarly, an imbalance is evident among editors-in-chief of the ID journals, with a notable predominance of men (67.1%) [34]. In an analysis encompassing 44 ID-related journals, women constituted only 33% of the 2,786 editors. More-over, among editors-in-chief exercising significant decision-making authority, a mere 26% were women, while 74% were men. This disparity persists across the group of associate and feature editors, as well as advisory and board members. Notably, the latter category has the highest percentage of women of the three groups (31% women vs 69% men), but with less decision-making power [11]. Both studies underscore a crucial determinant for a woman to be first author: the gender composition of journal editorial boards. Specifically, the presence of female editors is the most important variable to increased opportunities for women authors, as well as having a women's workforce [11, 19, 34].

This highlights two key observations: firstly, shows that women are the main revolutionaries, pioneering in setting the example, paving the way and creating new opportunities for themselves and other women [1]. Secondly, data has shown that male editors, choose more frequently male authors, favoring the inequity and perpetuating the exclusion of women. Consequently, this demonstrates the necessity of gender balance, as women's efforts alone prove insufficient to redress these imbalances and injustices. Moreover, certain journals, have worked in these paths to close the gaps, but a lot of work still be done and many challenges remain [8, 40].

These disparities in female representation persist across all medical specialties, including urology, surgery, gynecology and cardiology, with surgical specialties exhibiting the most pronounced gender gaps [12, 41]. Also, there is a lack of investigation in this field in many contexts, such as in Latin America.

Participation of Women within HIV is Key

Considering that in the last decade more than half of the new HIV diagnoses were made in adolescent girls and young women, it has become more evident that research and programs in the HIV field constantly fail to represent the female population, consequently, it is concerning that there are very few initiatives to enhance women engagement in research both as authors and as participants [2]. It is clear that women’s perspective in the design and development of trials and research, help to raise pertinent questions that target the diverse challenges that they have to face as a gender, and it is completely foreseeable that these initiatives are most likely to come from a female rather than a male perspective [1].

Certainly, many women were able to overcome the gender barrier and have accomplished monumental advances in the HIV field, for instance, findings about neural tube defects associated with mothers’ exposure to dolutegravir (DTG) at conception, were reported from a clinical trial conducted by women, thus reinforcing the female´s role in shaping research agendas [42]. Another wonderful examples, is the IMPAACT collaboration led entirely by female researchers, which is one of the biggest cohorts to include women that aims to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of DTG in maternal use; and HPTN 084, a phase 3 study on HIV prevention with long acting cabotegravir that focused specifically on cisgender woman, a population often overlooked in previous reports [43,44,45]. Once again, it is not surprising that both of these studies were designed, and are being conducted by women as well. Besides, women authorship has also contributed to groundbreaking research and breakthroughs in the HIV field even in the context of emerging diseases. One recent example was during Mpox outbreak in 2022 when female researcher lead one of the first cohorts to include patients with advanced HIV and was the first to propose necrotizing and disseminated form of Mpox as an AIDS-defining condition [46].

Despite those great efforts that have been achieved, it was not until recent regulations, that gender and sex were encouraged to be considered as variables in research design, recruitment, and publication [47, 48].

Regarding the participation of women as study subjects, a qualitative study in Switzerland revealed that factors associated with non-participation in clinical trials include familial responsibilities, the disregard of women’s social roles and their health concerns; these are determining barriers that interfere with their decision to be part of a study [49].

Unfortunately, this situation contributes to the invisibility of the unique challenges that women with HIV (WWH) have to endure, and it is why more studies targeting woman (like the ones mentioned above), and transgender woman are needed. Likewise, there is one specific situation in which WWH are not only overlooked, but excluded as participants from clinical trials, and it is pregnancy. Although the IMPAACT collaboration and the ACTG network have worked tireless to overcome this gap, in many countries of Latin America for example, including pregnant women into clinical trial are paradoxically restricted by their local regulatory entities [50].

Furthermore, this exclusion of WWH in particular contexts such as pregnancy, postpartum and lactation, has critical implications, such as not exploring optimal and safe regimens of treatment for women across all phases of their lives [1, 2]. This raises the interrogative of what else are we overlooking by neglecting to include this demographic in clinical research. By excluding women in these crucial life stages, we potentially miss results that could enlighten us about adverse effects or specific medical situations that can be beneficial for women.

Similarly, it is just as important to include women across all phases of their lives in clinical studies as it is to enhance cultural and ethnical diversity in research agendas and authorships [37]. Although, there have been some undeniable efforts to find new regimens for women and minorities, such as the Ilana study, which included racially minoritized people, elders and women to evaluate the results of injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine instead of daily pills [51]. It has been proven time and again that gender diverse people, particularly from different racial and ethnic groups continue to be underrepresented in research and many challenges still remain [52].

Therefore, inclusion and diversity are key to address as many gaps as possible within female clinical research.

Solutions

In elucidating the manifold obstacles confronting women striving for parity with their male counterparts, it is noteworthy to recognize the achievements of those who have not only reached their goals but surpassed them [37]. Nonetheless, significant changes are imperative to foster genuine equity in career trajectories between women and men in the realms of science and academia. This necessitates a series of reforms. A selection of measures that have been demonstrated to enhance opportunities and the environment is presented in the paragraphs that follow.

Early Approach to Women in Science

Gender bias training is a widely adopted strategy in medical and research institutions, as well as among journal editors [17]. Its significance lies in equipping women with the ability to identify instances of workplace gender and sexual violence and abuse, empowering them to demand justice when necessary and raising awareness of these issues within their respective working environments [53].

As evidenced, it is paramount for female doctors to receive support since the outset of their medical training. Proposals have been made for offering courses to reinforce self-assurance and negotiation abilities. For instance, Anna Bonna’s research illustrates how confidence and knowledge increase after less than a day of coaching in five different forms of communication skills among female young physicians [35].

Another crucial approach is to establish efficient mentorship initiatives. Research indicates that these programs benefit not only the mentor and mentee, but also the institution as a whole. They foster networking, gender inclusion, motivation, a sense of belonging, and mitigate “brain drain” [40, 54, 55]. Since they are both women, mentorship can facilitate the development of a relationship of trust, where the mentee seeks advice, answers, hope and guidance in navigating overwhelming challenges in both personal and professional spheres, such as the achieving a balance between academic and personal life [21, 55]. Unfortunately, institutions, particularly in low-medium income countries, often fail to recognize the value of mentorship efforts. As previously mentioned, female scientist have a heavy workload, and by assuming additional responsibilities within mentorship roles, they look for recognition, whether financial or academic [55]. Since effective mentoring needs training and courses. Guiding a woman in training entails a profound sense of responsibility and empathy, enabling her to envision possibilities beyond her current self-beliefs [56]. It entails providing support and instilling certainty that the answer lies within her, and she possesses the capabilities to attain it. Mentoring women should be acknowledged as an academic endeavor in its own right.

Seeking Equity in Science

In order to ensure equitable decision-making devoid of favoritism beyond merit, transparency and affirmative actions towards equity should be implemented in the allocation of grants, scholarships and adscriptions [19, 32, 34]. Additionally, to safeguard against any potential biases, proposal have been made for grants and research papers to be submitted anonymously, with the gender of the submitter remaining undisclosed until acceptance [15]. It has been described that there are female scientists that opt not to submit their articles when they aware that the editorial and directive board composition predominantly are men [34].

As previously noted, gender disparities persist in salary structures. Since women would be leaving a place with fewer privileges from the start, it is much fairer to pay them the same as men from the beginning rather than having a constant annual increase rate or equivalent to that of men [33].

As mentioned, motherhood among female physicians will benefit when the system genuinely recognizes the challenges they encounter. This recognition can be manifested through measures such as honoring full maternity leaves, providing extended periods without academic repercussions, and refraining from engaging in harassing behaviors, all of which contribute to fostering a sense of belonging within the institution [20, 22]. Additionally, it is imperative to provide decent lactation rooms, to alleviate the disproportionate burden of caregiving responsibilities placed on women and offering a safe daycare options for their children [17, 21, 25].

Incorporating existing data on women into clinical practice is imperative for gender-focused research, also to report every outcome by sex and gender [47]. Moreover, the gradual yet steady improvement observed with the implementation of mandatory gender quotas underscores the necessity for their enforcement. Moreover, the gradual yet steady improvement observed with the implementation of mandatory gender quotas underscores the necessity for their enforcement. While much work remains to be done, this review aims to acknowledge the great achievements in the HIV research community that has proven that equity is feasible and to express gratitude to women who have paved the way in the HIV scientific community. Hopefully, it will inspire young researchers to believe that our goals are achievable, and that we can close the gap. Additionally, we advocate for organizations to recognize the importance of providing more opportunities and spaces for women in the scientific community.

Conclusions

It remains critical to draw attention to the injustices, discrimination, inequalities and challenges that women encounter in their pursuit for equal status when compared to men in the medical scientific careers.

Such initiatives mentioned, would provide women physicians with competencies requisite for their next steps, including the confidence to apply to their desired fellowship or postgraduate programs, negotiate equitable salaries compared to their male counterparts, and starting to adopt and cultivate leadership-oriented attitudes.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Orkin C, Apea V. International Women’s Day—how can I help? Lancet HIV. 2022;9:e228–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00060-1.

The Lancet HIV. Women lead the way in the HIV response. Lancet HIV. 2024;11: e131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(24)00040-7.

Manne-Goehler J, Kapoor N, Blumenthal DM, Stead W. Sex Differences in Achievement and Faculty Rank in Academic Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:290–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz200.

UNAIDS Full report — In Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NY-SA 3.0 IGO. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update_en.pdf. Accessed 2 Mar 2024.

Justice AC, Goetz MB, Stewart CN, Hogan BC, Humes E, Luz PM, et al. Delayed presentation of HIV among older individuals: a growing problem. Lancet HIV. 2022;9:e269–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00003-0.

Smith TK, Larson EL. HIV Sexual Risk Behavior in Older Black Women: A Systematic Review. Women’s Health Issues. 2015;25:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2014.09.002.

CENSIDA. BOLETÍN DE ATENCIÓN INTEGRAL DE PERSONAS VIVIENDO CON VIH 2022;8(3). Available: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/764470/BOLETIN_DAI_TERCER_TRIMESTRE_2022.pdf. Accessed 10 Mar 2024

Smith JA. Editorial comment—the persistent publication glass ceiling. ANZ J Surg. 2023;93:103–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/ANS.18300.

Koelbl H. The extraordinary Path of Nobel Laureate Françoise Barré-Sinoussi | The MIT Press Reader n.d.; https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-extraordinary-path-of-nobel-laureate-francoise-barre-sinoussi/. Accessed 15 Mar 2024.

UNESCO Publishing. UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. 2015. Available: https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/unesco-science-report-towards-2030-part1.pdf. Accessedate 15 Mar 2024.

Barajas-Ochoa A, Ramirez-Trejo M, Gradilla-Magaña P, Dash A, Raybould J. Bearman G Gender balance in infectious diseases and hospital epidemiology journals. Antimicrob Steward Health Epidemiol. 2023;3(1):e190. https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2023.481.

Hancı V, Yakar MN, Shermatov N, Kara F, İbişoğlu E, Oltulu M, et al. The gender composition of the members of the editorial board of toxicology journals: Assessment of gender equality. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;134:413–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13968.

Bennet H. Women as Practitioners of Midwifery. The Lancet. 1870;95:887–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)68011-0.

What researchers think about the culture they work in n.d. https://wellcome.org/reports/what-researchers-think-about-research-culture. Accessed 20 Mar 2024.

Lancet T. Power and bullying in research. The Lancet. 2022;399:695. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02869-5.

Täuber S, Mahmoudi M. How bullying becomes a career tool. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6:475–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01311-z.

Stead W, Manne-Goehler J, Blackshear L, Marcelin JR, Salles A, del Rio C, et al. Wondering If I’d Get There Quicker If I Was a Man: Factors Contributing to Delayed Academic Advancement of Women in Infectious Diseases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(1):ofac660. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac660.

Moss SE, Mahmoudi M. STEM the bullying: An empirical investigation of abusive supervision in academic science. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101121.

Pinho-Gomes A-C, Woodward M. Redressing the gender imbalance across the publishing system. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1401–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00418-2.

Golden-Judge CP, Katz-Dotters SK, Weber JM, Pieper CF, Gray BA. Parenthood and Medical Training: Challenges and Experiences of Physician Moms in the US. Teach Learn Med. 2024;36:43–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2022.2141750.

Chesak SS, Yngve KC, Taylor JM, Voth ER, Bhagra A. Challenges and Solutions for Physician Mothers: A Critical Review of the Literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:1578–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.10.008.

Polan RM, Mattei LH, Barber EL. The Motherhood Penalty in Obstetrics and Gynecology Training. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:9–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004633.

Bakkensen JB, Smith KS, Cheung EO, Moreno PI, Goldman KN, Lawson AK, et al. Childbearing, Infertility, and Career Trajectories Among Women in Medicine. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6: e2326192. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.26192.

Abbasi K. Women and medicine: exploited as staff and as patients. BMJ. 2024;384: q394. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.Q394.

Dean E. Doctor parents and childcare: the untold toll revealed. BMJ. 2024;384: q128. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.Q128.

ONU Mujeres | Explicativo: Los efectos del COVID-19 sobre las mujeres y las niñas n.d. https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/explainer/covid19/es/index.html. Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

Halley MC, Mathews KS, Diamond LC, Linos E, Sarkar U, Mangurian C, et al. The Intersection of Work and Home Challenges Faced by Physician Mothers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. J Womens Health. 2021;30:514–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8964.

Patel SI, Ghebre R, Dwivedi R, Macheledt K, Watson S, Duffy BL, et al. Academic clinician frontline-worker wellbeing and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic experience: Were there gender differences? Prev Med Rep. 2023;36: 102517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102517.

Weinreich HM, Kotini-Shah P, Man B, Pobee R, Hirshfield LE, Risman BJ, et al. Work-Life Balance and Academic Productivity Among College of Medicine Faculty During the Evolution of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The New Normal. Women’s Health Reports. 2023;4:367–80. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2023.0007.

Obladen M. From Exclusion to Glass Ceiling: A History of Women in Neonatal Medicine. Neonatology. 2023;120:381–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000530311.

Galán-Muros V, Bouckaert M, Roser J. POLICY BRIEF THE REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN ACADEMIA AND HIGHER EDUCATION MANAGEMENT POSITIONS. Unesco-Iesalc. 2023;16:9.

Stead W, Manne-Goehler J, Krakower D, Marcelin J, Salles A, Del Rio C. Peering Through the Glass Ceiling: A Mixed Methods Study of Faculty Perceptions of Gender Barriers to Academic Advancement in Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:S528–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa166.

Catenaccio E, Rochlin JM, Simon HK. Addressing Gender-Based Disparities in Earning Potential in Academic Medicine. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e220067–e220067. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2022.0067.

Last K, Hübsch L, Cevik M, Wolkewitz M, Müller SE, Huttner A, et al. Association between women’s authorship and women’s editorship in infectious diseases journals: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1455–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00367-X.

Bona A, Ahmed R, Falvo L, Welch J, Heniff M, Cooper D, et al. Closing the gender gap in medicine: the impact of a simulation-based confidence and negotiation course for women in graduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-023-04170-Y/TABLES/7.

Fischer LH, Bajaj AK. Learning How to Ask: Women and Negotiation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:753–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003063.

Gilsdorf JR, Zimmer SM. Remembering and Enhancing the Impact of Women in Infectious Diseases. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:S543–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/INFDIS/JIAA235.

Paulise L. 75% Of Women Executives Experience Imposter Syndrome In The Workplace 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lucianapaulise/2023/03/08/75-of-women-executives-experience-imposter-syndrome-in-the-workplace/?sh=3dcb0f5e6899. Accessed 26 Mar 2024.

Iwai Y, Yu AYL, Thomas SM, Fayanju OA, Sudan R, Bynum DL, et al. Leadership and Impostor Syndrome in Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2023;237:585–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/XCS.0000000000000788.

Sears CL, Powderly WG, Auwaerter PG, Alexander BD, File TM. Pathways to Leadership: Reflections of Recent Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Leaders During Conception and Launch of the Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity Movement Within the IDSA. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:S554–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/INFDIS/JIAA297.

Burg ML, Kohli P, Ha N, Mora R, Kurup T, Sidhu H, et al. Gender disparities among publications within international sexual medicine urology journals and the impact of blinding in the review process. J Sex Med. 2024;21(2):117–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/JSXMED/QDAD152.

Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, Jacobson DL, Brummel S, Mayondi G, et al. Neural-Tube Defects and Antiretroviral Treatment Regimens in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:827–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA1905230.

Delany-Moretlwe S, Hughes JP, Bock P, Ouma SG, Hunidzarira P, Kalonji D, et al. Cabotegravir for the prevention of HIV-1 in women: results from HPTN 084, a phase 3, randomised clinical trial. The Lancet. 2022;399:1779–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00538-4.

Landovitz RJ, Hanscom BS, Clement ME, Tran HV, Kallas EG, Magnus M, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-acting cabotegravir compared with daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate plus emtricitabine to prevent HIV infection in cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men 1 year after study unblinding: a secondary analysis of the phase 2b and 3 HPTN 083 randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2023;10:e767–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(23)00261-8. Accessed 18 Mar 2024.

IMPAACT 2023 n.d. https://www.impaactnetwork.org/studies/impaact2023.

Mitjà O, Alemany A, Marks M, Lezama Mora JI, Rodríguez-Aldama JC, Torres Silva MS, et al. Mpox in people with advanced HIV infection: a global case series. The Lancet. 2023;401:939–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00273-8.

Johnson PA. Science and Sex—A Bold Agenda for Women’s Health. JAMA Intern Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.0174.

Heidari S, Fernandez DGE, Coates A, Hosseinpoor AR, Asma S, Farrar J, et al. WHO’s adoption of SAGER guidelines and GATHER: setting standards for better science with sex and gender in mind. The Lancet. 2024;403:226–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02807-6.

Courvoisier N, Storari C, Lesage S, Vittoz L, Barbieux C, Peytremann-Bridevaux I, et al. Facilitators and barriers of women’s participation in HIV clinical research in Switzerland: A qualitative study. HIV Med. 2022;23:441–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/HIV.13259. Accessed 30 Mar 2024.

Reglamento de la Ley General de Salud en Materia de Investigación para la Salud n.d. https://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/compi/rlgsmis.html.

Farooq HZ, Apea V, Kasadha B, Ullah S, Hilton-Smith G, Haley A, et al. Study protocol: the ILANA study - exploring optimal implementation strategies for long-acting antiretroviral therapy to ensure equity in clinical care and policy for women, racially minoritised people and older people living with HIV in the UK - a qualitative multiphase longitudinal study design. BMJ Open. 2023;13(7):e070666. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070666.

Barr E, Marshall LJ, Collins LF, Godfrey C, St Vil N, Stockman JK, et al. Centring the health of women across the HIV research continuum. Lancet HIV. 2024;11:e186–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(24)00004-3.

Cronin MR, Zavaleta ES, Beltran RS, Esparza M, Payne AR, Termini V, et al. Testing the effectiveness of interactive training on sexual harassment and assault in field science. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):523. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-023-49203-0.

Lukela JR, Finta M, Secrest K, Wiggins J. Facilitated Peer Mentorship for Women Internal Medicine Residents: An Early Intervention to Address Gender Disparities. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15:389–91. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00765.1.

Brizuela V, Chebet JJ, Thorson A. Supporting early-career women researchers: lessons from a global mentorship programme. Glob Health Action. 2023;16(1):2162228. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2022.2162228.

Koven S. What Is a Mentor? N Engl J Med. 2024;390:683–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2313304.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. C. R contributed with the conception, supervision, design and critical revision of the manuscript. Most of the writing, design and conceptualization of the main text were perfomed by K. J. C. N. S. M helped with the writing and revision. All authors have read and agreed to the submited version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Juárez-Campos, K., Sierra-Barajas, N. & Crabtree-Ramírez, B. “The role of Women in Leadership, Academia & Advocacy in the field of HIV”. Curr Trop Med Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-024-00327-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-024-00327-x