Abstract

Purpose of Review

COVID-19 pandemic led to a decline in living kidney donor evaluations and transplants. This was due to concerns for donor and recipient safety, restrictions on elective cases, and diversion of staff and resources in centers with a higher incidence of COVID-19 infections. Telehealth was explored as a strategy to continue living donor evaluations during the pandemic, but faced barriers including restrictive physician licensing, reduced reimbursement, lack of infrastructure, prohibitive local policies, limited exam, and personal biases. This review highlights these barriers and potential solutions.

Recent Findings

Telehealth usage in the transplant population improves medication adherence, reduces hospitalization rates for recipients, and makes living donor evaluation convenient. Transplant centers have implemented telehealth successfully for living kidney donor evaluations. Broad use of telemedicine will be possible only if policies support the changing landscape of healthcare delivery.

Summary

Telehealth may increase access to timely kidney transplants by expediting living kidney donor evaluations. However, supportive infrastructure, regulatory policies, and reimbursement are needed to sustain access to telehealth for living kidney donor evaluation and care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The boundaries for deceased donor organ pool expansion continue to be pushed with usage of kidneys with high kidney donor profile index (KDPI), dual kidney transplantation, and kidneys from Hepatitis-C viremic donors. Despite the broader use of deceased donor organs, there is a mismatch between demand and access to donor organs. There are 92,951 kidney waitlisted patients as of Feb 2021 and only 22,817 kidney transplants were done nationally in 2020 [1]. The 10-year graft survival rates for deceased donor and live donor kidney transplants done in 2005 were 47.2% and 62.7%, respectively [2]. This makes living kidney donor transplantation the most preferred renal replacement therapy.

The number of kidney transplants decreased substantially after a national public health emergency was declared in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on a survey in March 2020, > 75% of kidney and liver programs either suspended transplants or were operating under restrictions [3]. A follow-up survey in May 2020 showed that the suspension of living kidney donor transplantation decreased from 72% of programs in March to 30% in May. Despite transplant centers gradually resuming kidney transplantation in the summer of 2020, the overall volume of kidney transplants never reached the previous year’s total, with a 2.5% decline in 2020 compared to 2019 [1]. Total number of kidney transplant in 2020 were 22,817 compared to 23,401 in 2019. Live donor kidney transplants in 2020 were 5234 and 6867 in 2019 decline of 23.7% in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted significant deficiencies in healthcare delivery and the need for options beyond conventional ambulatory setting for donor evaluations [4, 5•].

Historically, the adoption of telehealth had been slow, due to logistic challenges, inadequate reimbursement, and state licensing limitations to name a few. With the advent of the smartphone and mobile medical devices, the widespread expansion of mobile health (mHealth) became possible. Mobile apps are being used to increase live organ donation. This technology is being used in various format all cross the nation [6]. Today, over 80% of adults in the USA own a smartphone, as reported by Pews Research Center [7]. The ability to access the telemedicine platform through a variety of simple mobile applications increased patient participation by removing technological barriers and enabled seamless virtual patient-provider interactions.

Often, the terms telehealth and telemedicine are used interchangeably. Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) defines telehealth as the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical healthcare, patient and professional health-related education, public health, and health administration. These technologies include videoconferencing, the internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and wireless communications [8]. Telehealth differs from telemedicine since it encompasses a broader scope of remote healthcare services. Telemedicine refers specifically to remote clinical services [8].

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Transplant Program was the first to evaluate the effectiveness of telehealth use for kidney transplant evaluation. The program demonstrated increased access to kidney transplant evaluation by introducing web-based referrals and telehealth [9].Significant improvement in the median time to evaluation and a higher percentage of patients with appointments were reported within 30 days of using the web-based platform [9].

A Cochrane review of over 90 studies showed improved outcomes with telehealth when compared to conventional practice for patients with chronic kidney disease/kidney transplantation [10].Some of these examples highlighted the definite role of telehealth for (i) providing medical care for chronic kidney disease to monitor salt intake and lower blood pressure [11]; (ii) assessing frailty in kidney waitlisted patients [12]; and (iii) improving transplant medication safety [13]. It is well established that the use of telehealth improves outcomes, reduces hospitalization, reduces cost, and is comparable to ambulatory visits as a healthcare delivery model [10]. A previously validated in-person intervention, Talking About Live Kidney Donation Social Worker Intervention (TALK-SWI), demonstrated improved access to living kidney donor transplants through the face-to-face delivery of education and social support. The same program was also successful when implemented via a telehealth format [14].

COVID-19 Pandemic as a Catalyst for Telehealth

Historically, the regulations regarding telehealth are varied and inconsistent among all the states. For example, North Carolina requires a certain geographical distance between two participating parties and South Dakota requires that the two involved parties cannot be in the same county. Only 32 states reimburse for a facility fee, which can be a significant expense for a small institution if not reimbursed. Thirty states require special informed consent, and prescription regulations are variable among states as well [15–18].

COVID-19 affected living kidney donor transplant with many programs reporting a decline in living donor evaluations and subsequent transplants [19•]. This was due to concerns for donor and recipient safety, restrictions on elective cases, and diversion of staff and resources in centers with a higher incidence of COVID-19 infections. During those times, many programs used various audiovisual platforms to continue living donor evaluations [3, 19•, 20]. The need to evaluate living donors in the safety of their homes while observing social distancing became vital [4]. Telehealth delivered through a HIPAA compliant platform was heavily utilized as an innovative care delivery model [5•].

A primary driver for rapid telehealth adoption during the COVID-19 pandemic was the payment reform guidelines that were urgently put together under Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. This granted some leniency towards licensures and telehealth reimbursements. This pandemic was an unfortunate yet effective catalyst to address two major barriers to telehealth: consumer readiness to try new care delivery models and insurance coverage [21••]. Telemedicine enabled physicians to connect with the patients safely and seamlessly during their most vulnerable times. Under the CMS 1135 Coronavirus waivers, Medicare pays for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telemedicine across the country [22]. Likewise, many (but not all) states have issued licensure waivers with respect to telehealth for out-of-state medical licenses during the pandemic [23].

Establishing a Telehealth Program

Previously, mobile technology and questionnaires [24]. have been used to study patient’s attitudes towards remote living donor evaluation processes. Kumar et al. demonstrated an almost sixfold increase in living donor referrals compared with a control group (with no access to social media for donation-related posts) using social media [25]. Interestingly, their study indicated that this tool may be valuable even for those with a previously limited or nonexistent social media presence. Both these studies highlight the importance of mobile communications to open the possibility for individual and mass education about living donation and the potential for increasing living donor referral through non-directed donors.

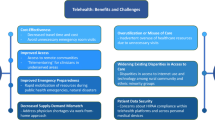

The telehealth model for living donor evaluations has many advantages but comes with its own set of challenges.

Transplant programs that plan to launch a telehealth component need to have robust technical support, strong infrastructure for concurrent connections, identified super-users to troubleshoot provider, and support staff to address patient technological challenges timely (Table 1). The chosen telehealth platform should be compatible with already existing electronic health records (EHR) in addition to being HIPPA compliant.

Living Kidney Donor Telehealth Program—a Single-Center Experience

Successful use of telehealth for living kidney donor evaluation was presented as an abstract at the American Transplant Congress 2020 by Yadav et al. This study reports that over 60% of their potential living kidney donors evaluated via a telehealth platform since 2016 proceeded to donation [26••]. Telehealth implementation was described all through the peri-transplant process such as living kidney donor evaluation, transplant candidate evaluation, and post-transplant follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic [21••].

An example of a potential workflow for a telehealth-based living kidney donor evaluation before the pandemic is outlined in Fig. 1. Briefly, web links for educational videos were sent to potential donors, followed by contact with the independent living donor advocate and the nurse coordinator to review the donor evaluation consent. Then, a telemedicine evaluation was completed by the transplant nephrologist and/or the transplant surgeon and imaging studies were pursued locally. A prerequisite step in this process included an evaluation by a primary physician locally to document vital signs and physical exam. This step was critical for non-local donors. Additional members of the living donor team completed their evaluations via HIPAA compliant audiovisual platform. A provisional candidacy decision was made in multidisciplinary meeting. Potential donors then traveled to the transplant center about 10 days prior to the provisional donation date to meet with various members of the team in person and completed final preadmission testing (including CT scan abdomen) and any remaining steps of the evaluation. This swift virtual workup additionally made the process more financially feasible for donors by reducing the direct and indirect costs of living kidney donation. During the pandemic, patients were examined virtually using Webside exam (Table 2) and complete exam is deferred until the visit 1–2 weeks before the final in-person evaluation. This group utilized preexisting donor telehealth model to continue evaluations during the pandemic. However, overall evaluations did decrease like the national experience [19•]. Program identified dedicated staff who ensured patients were “telehealth ready” by providing real-time technical assistance and test sessions prior to appointments. The existing infrastructure and prior usage experience with established workflows immensely helped to pivot pre- and post-ambulatory transplant services to a telehealth model.

The average financial cost incurred by a living kidney donor in America is about $5000 [27] and most of this is lodging, travel, and time off from work as well as dependent care expenses. A 1 or 2-day evaluation may help reduce costs by reducing the number of trips to the center costs may be substantial for donor candidates who must fly out of state to the transplant center to undergo an initial workup. Telehealth evaluation can help the process more financially neutral for the donor by reducing travel costs and lost time from work and other activities. Blood typing for donors can be done at any lab but transplant centers frequently request donor blood for HLA typing. Notably, we are in the process of validating a workflow where potential donor’s saliva can be utilized for donor HLA typing, to reduce trips to a lab in the initial screening phase.

Barriers to Telehealth

Barriers to the implementation of telehealth can be broadly divided into institutional, provider, and patient barriers [28].

Institutional Barriers

The initial cost of establishing telehealth infrastructure while encountering an inconsistent reimbursement model is a challenge for institutions. However, in the long run, the ability to seamlessly conduct living donor candidate evaluations, to facilitate more transplants, while also minimizing donor expenses is a win–win scenario. Medicare spends about $93,000 annually to maintain a patient on hemodialysis and about $37,000 on a kidney transplant recipient beyond the first year of transplant [29]. Telehealth options not only support the living donor program by removing some of the donor financial disincentives, but the same infrastructure is expected to support many clinical practices beyond the transplant program. Thus, investing and growing a transplant telehealth program that improves access to living donor transplantation can result in higher patient satisfaction score along with reputational advantages, and long-term financial benefits for Medicare. In consultation with legal and risk management teams, e-consenting services may also be incorporated to expeditiously obtain donor and recipient evaluation consents and thus maintain regulatory compliance.

Provider Barriers

A French study found that nephrologists were comfortable using telemedicine, but also experienced barriers related to logistics, billing, and technical problems [30]. Licensing regulations across state borders in the USA limits telehealth reach tremendously. Relaxed restriction during the pandemic and expedited temporary licensing facilitated access to care across state lines. However, the bias against virtual exams, unreliable insurance reimbursement, concerns among staff about unconventional healthcare delivery model, and malpractice coverage continue to limit physician participation. Importantly, donor candidates have had extensive interviews, imaging, and lab work as part of living kidney donor evaluation that can be relied upon to make a tentative informed decision. The “Webside” exam summarized in Table 2 is an important tool [21••] that can be used for donor and recipient candidates. Other pertinent information like distribution of weight, body mass index (BMI), and some assessment of home environment and living conditions can be elucidated during the telehealth exam.

A set of updated vital signs can be obtained at a local laboratory chain by providing a vital sign order, from local primary care physician visit, or even local fire stations can provide vital signs such as weight, height, and blood pressure. Telehealth can be used for preoperative assessment effectively, and has been established during pandemic.

Patient barriers

Given that > 80% of Americans are smartphone users [7] and most have internet access via phone services, telehealth seems to be an accessible modality for healthcare delivery both during and post-pandemic. However, patients may have limited data plans or high-speed access that could pose a hindrance to telehealth access. Furthermore, lack of understanding of technology, “uneasiness” regarding communication over audiovisual medium, concerns of privacy, and familiarity within person visits can lead to slow adoption rates by patients. Patient education, technological support, and mock visit preps may help overcome such barriers and increase adoption and utility [31].

Future Directions

Telehealth utilization in the transplant population has been shown to improve medication adherence, reduce hospitalization rates for recipients, and make living donor evaluation more accessible and convenient [17, 26••, 29, 32–36]. This is a feasible and an efficient care delivery platform if reimbursement is ensured to providers. Loss of originating site facility fee is counterbalanced by expedited living donor work up and potential for increased live donor transplants. The wider implementation of telemedicine is possible only if policies align with the changing landscape of healthcare delivery. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a stimulus to learn and adapt quickly. Currently, there is no best practice guidance available for living kidney donor evaluation via telehealth and often programs are left to formulate their own. Collaborative efforts to advance supportive infrastructure, regulatory policies, and reimbursement are vital. This will build the momentum gained during the COVID-19 pandemic for continued access to telehealth for living kidney donor evaluation and care.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/citing-data/. Accessed 02/15/2021.

https://www.srtr.org/reports/srtroptn-annual-data-report/2020. Accessed 02/15/2021.

Boyarsky BJ, Ruck JM, Chiang TP, et al. Evolving impact of COVID-19 on transplant center practices and policies in the United States. Clin Transplant. 2020: e14086.

Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020;26(5):309–15

Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. The New Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679–81. One of the first articles discussing telehealth need especially during pandemic.

Kumar K, King EA, Muzaale AD, et al. A smartphone app for increasing live organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(12):3548–53.

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/. Accessed 06/12/2021.

Health IT Government. https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-telehealth-how-telehealth-different-telemedicine. Accessed 02/15/2021.

Forbes RC, Broman KK, Johnson TB, et al. Implementation of telehealth is associated with improved timeliness to kidney transplant waitlist evaluation. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(7):485–91.

Flodgren G, Rachas A, Farmer AJ, Inzitari M, Shepperd S. Interactive telemedicine: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(9):Cd002098.

Stevenson JK, Campbell ZC, Webster AC, et al. eHealth interventions for people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;8(8):Cd012379.

Watford DJ, Cheng XS, Han J, et al. Toward telemedicine-compatible physical functioning assessments in kidney transplant candidates. Clin Transplant. 2021;35(2):e14173.

Fleming JN, Treiber F, McGillicuddy J, Gebregziabher M, Taber DJ. Improving transplant medication safety through a pharmacist-empowered, patient-centered, mHealth-based intervention: TRANSAFE Rx study protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(3):e59.

Cabacungan AN, Diamantidis CJ, St Clair Russell J, et al. Development of a telehealth intervention to improve access to live donor kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(3):665–75.

Grome L, Jalalabadi F, Fordis CM Jr, Sussman NL, Reece EM. Bootstrapping your telehealth program. Semin Plast Surg. 2018;32(4):162–5.

Savikko J, Rauta V. Implementing eHealth in kidney transplantation in Finland. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(2):464–5.

Udayaraj UP, Watson O, Ben-Shlomo Y, et al. Establishing a tele-clinic service for kidney transplant recipients through a patient-codesigned quality improvement project. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(2):e000427.

Winsett RP, Thompson D, Gower G, Gaber AO. Introducing telemedicine into a transplant outpatient clinic. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(4):215–6.

Lentine KL, Vest LS, Schnitzler MA, et al. Survey of US living kidney donation and transplantation practices in the COVID-19 era. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(11):1894–905. Highlighted how COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on living kidney transplants by altering pratcices in the centers.

Wolf J, Rubin J, Bossie A, Lizcano J. Acceptance of telemedicine by kidney transplant recipients during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study of patient experiences. Trends Trans. 2021;14(2). https://doi.org/10.15761/TiT.1000294.

Yadav A, Caldararo K, Singh P. Optimising the use of telemedicine in a kidney transplant programme during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;1357633X20942632. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20942632. This articles proposes the strategy used at their center where they optimized telehealth and overcame significant barriers telehealth posed before and during COVID-19 pandemic. This mentions all aspect of kidney transplantation, recipient-donor evaluation, and post-transplant follow-up.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed 29 Oct 2021.

Federation of State Medical Boards. States waiving telehealth licensure requirements. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/pdf/states-waiving-licensure-requirements-for-telehealth-in-response-to-covid-19.pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2021.

Sieverdes JC, Nemeth LS, Magwood GS, et al. Patient-centered mHealth living donor transplant education program for African Americans: development and analysis. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(3):e84.

Fleming JN, Taber DJ, McElligott J, McGillicuddy JW, Treiber F. Mobile health in solid organ transplant: the time is now. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(9):2263–76.

Yadav Anju MMP, Singh Pooja Telehealth: a novel tool to make living donation simple and financially neutral. American Transplant Congress 2020. Abstract number B-030. This abstract discuss living kidney donor evaluations pre and during pandemic.

Przech S, Garg AX, Arnold JB, et al. Financial costs incurred by living kidney donors: a prospective cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(12):2847–57.

Concepcion BP, Forbes RC. The role of telemedicine in kidney transplantation: opportunities and challenges. Kidney360. 2020;1(5):420–3.

https://adr.usrds.org/2020/end-stage-renal-disease/9-healthcare-expenditures-for-persons-with-esrd. Accessed 2/19/21

Citarda S, Camarroque AL, Seret G, et al. e-Health in nephrology: 1(st) French survey on telenephrology. Nephrol Ther. 2019;15(6):452–60.

McGillicuddy JW, Weiland AK, Frenzel RM, et al. Patient attitudes toward mobile phone-based health monitoring: questionnaire study among kidney transplant recipients. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(1):e6.

Schmid A, Hils S, Kramer-Zucker A, et al. Telemedically supported case management of living-donor renal transplant recipients to optimize routine evidence-based aftercare: a single-center randomized controlled trial. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(6):1594–605.

Nerini E, Bruno F, Citterio F, Schena FP. Nonadherence to immunosuppressive therapy in kidney transplant recipients: can technology help? J Nephrol. 2016;29(5):627–36.

Taber DJ, Pilch NA, McGillicuddy JW, Mardis C, Treiber F, Fleming JN. Using informatics and mobile health to improve medication safety monitoring in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(15):1143–9.

O’Brien T, Russell CL, Tan A, Washington M, Hathaway D. An exploratory correlational study in the use of mobile technology among adult kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transplant. 2018;28(4):368–75.

Reber S, Scheel J, Stoessel L, et al. Mobile technology affinity in renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(1):92–8.

Mihalj M, Carrel T, Gregoric ID, et al. Telemedicine for preoperative assessment during a COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations for clinical care. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34(2):345–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Live Kidney Donation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yadav, A., Singh, P. Telehealth Use by Living Kidney Donor Transplant Programs During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: a Practical Approach. Curr Transpl Rep 8, 257–262 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-021-00339-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-021-00339-w