Abstract

Purpose of Review

The early detection of problematic Internet use (PIU) is essential to prevent the development of Internet use disorders (IUD). Although a variety of screening tools have already been developed and validated for this purpose, yet a consensus about optimal IUD assessment is still lacking. In this systematic review, we (i) describe the identified instruments for children and adolescents, (ii) critically examine their psychometric properties, and (iii) derive recommendations for particularly well-validated instruments.

Recent Findings

We conducted a systematic literature search in five databases on January 15, 2024. Of the initial 11,408 references identified, 511 studies were subjected to a full-text analysis resulting in a final inclusion of 70 studies. These studies validated a total of 31 instruments for PIU and IUD, including the Diagnostic Interview for Internet Addiction (DIA), a semi-structured interview. In terms of validation frequency, the Internet Addition Test (IAT) had the largest evidence base, followed by the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS). Only two of the measures examined were based on the current DSM-5 criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder.

Summary

Although no screening instrument was found to be clearly superior, the strongest recommendation can be made for CIUS, and Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale (GPIUS2). Overall, the quality of the included studies can only be rated as moderate. The IUD research field would benefit from clear cut-off scores and a clinical validation of (screening) instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The use of electronic devices has become a ubiquitous part of children’s and adolescents’ daily life [1]. Although there is no consensus yet for children and adolescents regarding recommendations on screen time, limitations of spending no more than 1–2 h daily on screens for recreational purposes are advised [2, 3]. However, previous studies found that the time spent on electronic devices in childhood and adolescence is rapidly increasing, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic [4, 5••, 6, 7•]. In extreme cases, such behavior can lead to problems akin to those of substance addictions, including psychological and interpersonal consequences such as loss of control, abstinence symptoms, tolerance development, and deceit of family and friends [8, 9]. Since Internet use disorders (IUD) may have a negative impact on the individual’s offline lives [10] with severe functional impairments and suffering [11••], this issue raises concerns among parents, teachers, clinicians, etc. about its adverse consequences [12], like school absenteeism [13] or mental health problems [14]. To prevent/counteract these negative consequences, it is important to identify PIU and initialize effective prevention and/or intervention strategies in a timely manner [7•, 15, 16•, 17].

Younger individuals have been identified as having a higher risk for problematic Internet use (PIU) behavior. While the prevalence of Internet-related disorders is about 1–2% in the general population [18, 19], higher prevalence rates up to 4% were found among adolescents aged 14 to 16 years [19]. A recent meta-analytic review implicates that due to the COVID-19 pandemic global prevalence of IUD increased significantly [20].

Notwithstanding the possible adverse effects and the acceptance of PIU as a significant global mental health issue [21], IUD is not officially recognized as mental disorder by not being incorporated into any of the new classification systems. To date, only the diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) is included in the appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) [22] as a condition for further study and in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th edition (ICD-11) as officially recognized disorder [23] based on available evidence as well as public health and clinical needs [24, 25].

Suitable screening tools and clinically validated instruments are indispensable to further explore the construct of PIU and to establish the clinical relevance of Internet addiction (IA) [7•]. Given the growing impact of Internet use through new technological tools [9, 26], the various scales on PIU and IUD and despite growing research interest in this behavioral addiction [27], to date, the assessment of PIU and IUD lacks clear recommendations regarding the most optimal tools, especially concerning the vulnerable group of younger age groups [28]. Previous reviews are quite outdated (e.g., [29,30,31]), and not limited to children and adolescents [29, 30]. Moreover, neither of these reviews provided an exhaustive overview of the available scales and its psychometric properties, nor provided clear recommendations for particularly well-validated instruments on the basis of a priori defined clear criteria. Therefore, this systematic review sought to provide a psychometric guide which would assist researchers and clinicians in their choice of adequate instruments. More specifically, we aim to identify instruments assessing PIU and IUD in children and adolescents, critically examine their psychometric properties, and finally derive recommendations for particularly well-validated instruments based on these characteristic values and other assessment criteria.

Methods

Study Procedure

A computer-assisted systematic search in the following five electronic databases was conducted based on corresponding key words considering the PRISMA-guidelines [32]: (1) PsycINFO (multi-field search; limitation to: “abstract”), (2) PubMed (advanced search; limitation to: “title/abstract”), (3) PsycArticles (multi-field search; limitation to: “abstract”), (4) Scopus (advanced search; limitation to: “title/abstract”), (5) Web of Science (advanced search; command: “all”).

In the next step, we conducted reference list searches of each of the included validation studies in order to obtain as many relevant reports as possible.

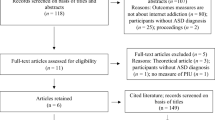

The review followed the guidelines and standards of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) for writing systematic reviews. A PRISMA flow chart of the entire literature search and study selection process is summarized in Fig. 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search was limited to articles published in peer-reviewed journals (document type articles) as well as primary studies written in English language. Further criteria were the inclusion of participants aged up to 18 years (maximum mean age sample: 18.9 years), the validation of (screening) instruments assessing IUD in general (no gaming or social network use disorder) with a detailed report of psychometric properties (more information than solely the reliability of the tool). Some studies did not conduct a systematic validation of an instrument, but used IUD (screening) instruments in empirical studies, providing partial evidence for psychometric properties. These studies have also been included in our review. We included studies that aimed at either developing a new scale or providing a psychometric evaluation of already existing instruments.

Analogously, studies evaluating other aspects of Internet use or studies including adults were excluded. Further exclusion criteria were qualitative studies, reviews, and meta-analyses. Other constructs such as problematic use of the smartphone or media in general were not considered to stick to a uniform construct. Furthermore, we excluded articles which generally only gave partial evidence of a scale’s psychometric properties (e.g., only assessing the reliability of a scale).

Search Strategy

We generated a search algorithm for PsycInfo in an iterative process. Subsequently, further systematic searches were conducted in the other four databases. Various keyword combinations were created and linked by using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR.” Moreover, truncations (*) and Wildcards ($) for possible additional characters were used to account for different variations and to include terms not yet taken into account. In addition, synonyms were included in the search strategy to achieve a higher/greater hit rate.

The final search in the academic databases took place on January 15, 2024, containing the following search term combination:

(“measur*” OR “tool#” OR “test*” OR “validat*” OR “psychometric*” OR “screen*” OR “diagnos*” OR “item#” OR “instrument#”) AND (“internet” AND “use disorder#” OR “addict*” OR “depend*” OR “abus*” OR “misus*” OR “problem*” OR “risk*” OR “hazard*” OR “compuls*” OR “obsess*”) AND (“child*” OR “adolesc*” OR “young age”).

Data Synthesis

Results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 in compliance with previous reviews on subtypes of IUD, like Gaming Disorder [33••] or Social Network Use Disorder [34]. In Table 1, study characteristics like sample size, age group, country of the validation samples, and sampling approach are presented. This is supplemented by information on the respective tool, such as language version, investigated construct, components, items, response format, and cut-off score.

To illustrate the psychometric properties of each scale, we extracted the relevant psychometric parameters from the validation studies and summarized the information in Table 2. If provided, we reported the dimensionality (method; factor structure), reliability (internal consistency; test–retest), and test refinement (Rasch/IRT; measurement invariance), as well as construct and criterion validity of the scale in question.

The reliability was assessed primarily with internal consistency (mainly Cronbach’s alpha); some studies also reported test–retest reliability (with Pearson’s correlation coefficient r). For construct/external validity, a significant correlation between PIU and IUD scales with other adequate assessment tools measuring a conceptually similar construct was considered. Criterion validity was defined by a significant association between the tool and variables related to Internet use, i.e., frequency or daily/average time spent on the Internet, in anticipation that these variables would be positively correlated with PIU and IUD.

Finally, we evaluated the psychometric properties and other criteria in a quick reference guide (QRG) in Table 3 yielding validation evidence for each study. Table 1 contains a final evaluation of tool characteristics being integrated across studies, i.e., that also considers the frequency of studies in which each criterion for a scale is covered.

The rating of the QRG was conducted by two independent coders (S.S. and L.H.). Any discrepancies between the coders in the ratings were resolved through discussion and by involving a third researcher (H.-J.R.).

In evaluating psychometric properties of the scales, we also referred to previous systematic reviews on special forms of IUD, like Gaming Disorder [33••] and Social Network Use Disorder [34]. The latter involves 13 criteria illustrated in Tables 3 and 1: (1) DSM-5 coverage, (2) ICD-11 coverage, (3) Cut-off score, (4) Longitudinal data, (5) Dimensionality, (6) Internal consistency, (7) Test–retest reliability, (8) Test refinement (i.e., Rasch; IRT; Measurement invariance), (9) External validity (i.e., convergent validity), (10) Use of clinical samples, (11) Impairment, (12) Wording, and (13) Quality of sampling approach.

Results of the Systematic Literature Search

The systematic literature search in the databases resulted in a total of 11,408 potentially relevant hits. After removing 4188 duplicates, 5405 were assessed as not relevant after reviewing the titles of the remaining 7220 non-redundant studies. Another 1304 articles were excluded after reading the abstract. Subsequently, 511 full texts were examined, which resulted in the exclusion of studies narrowing down to 68 articles (see Fig. 1 for details). The most common reason for exclusion was of methodological nature, i.e., the report of insufficient reliability criteria, mostly only Cronbach’s alpha. This information was not considered sufficient to assess the psychometric quality of the screening tool. In the next step, we conducted reference list searches of each of the 64 included reports for additional scales, yielding a total of 2 more reports. Finally, 70 studies validating 31 survey instruments were included.

Description of the Studies

The inclusion of 70 studies yielded a total of 31 tools to detect PIU and IUD in children and adolescents: (1) Chinese Internet Addiction Goldberg Scale (CIA-Goldberg) [35], (2) Chinese Internet Addiction Goldberg Scale – Young (CIA-Young) [35], (3) Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS) [36] [37], (4) Revised Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS-R) [38], (5) Chen Internet Addiction Scale – Short Form (CIAS-SF) [39•], (6) Chinese Internet Addiction Test (CIAT) [40], (7) Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], (8) Diagnostic Interview for Internet Addiction (DIA) [52], (9) Excessive Internet Use Scale (EIUS) [53], (10) Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 (GPIUS2) [54,55,56,57,58], (11) Internet Addiction Scale (IAS, (originally developed by Nichols and Nicki, 2004 [59]) [60], (12) Internet Addiction Scale (IAS, originally developed by Young, 1998 [61, 62]) [63], (13) Internet Addiction Test (IAT) [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80], (14) Internet Addiction Test – Adolescence version (IAT-A) [81], (15) IAT – Short version (IAT – Short) [82, 83], (16) brief Internet Addiction Questionnaire (bIAQ) [84], (17) Internet Disorder Scale (IDS-15) [85], (18) Initial screening scale [86], (19) Internet-user Assessment Screen [87], (20) Index of Problematic Online Experiences (I-POE) [88, 89], (21) Internet Related Experiences Questionnaire (IREQ) [90, 91], (22) Korean Scale for Internet Addiction (K-Scale) [92], (23) Online Cognition Scale (OCS) [93], (24) Problematic Internet Entertainment Use Scale for Adolescents (PIEUSA) [94, 95], (25) Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ) [96,97,98], (26) Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire – Short Form, 6 Items (PIUQ-SF-6) [99,100,101], (27) Problematic Internet use questionnaire – Short Form, 9 Items (PIUQ-SF-9) [97, 98, 102], (28) Problematic Internet Use Scale in adolescents (PIUS-a) [103], (29) Parental Version of Young Diagnostic Questionnaire (PYDQ) [104], (30) Short Problematic Internet Use Test (SPIUT) [105], and (31) Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire (YDQ) [106, 107].

These tools are available in a total of 17 languages: Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, English, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latvian, Lithuanian, Malay, Persian, Spanish, and Turkish. The samples were mostly recruited in Europe (n = 35), followed by Asia (n = 29), America (n = 4), and Africa (n = 1; Table 1).

Of all instruments, about half (n = 17) had an explicit reference to Internet addiction: CIA-Goldberg, CIA-Young, CIAS, CIAS-R, CIAS-SF, CIAT, DIA, IAS (Original: [59]), IAS (Original [61, 62]:), IAT, IAT-A, IAT – Short, bIAQ, IDS-15, IREQ, K-Scale, PYDQ, YDQ. The other half focused on problematic/excessive/compulsive Internet use: CIUS, EIUS, GPIUS2, Initial screening scale, Internet user Assessment Screen, I-POE, OCS, PIEUSA, PIUQ, PIUQ-SF-6, PIUQ-SF-9, PIUS-a, and SPIUT (Table 1).

Of the 31 scales, only 12 had been evaluated more than once in terms of their psychometric properties (CIAS, CIUS, GPIUS2, IAT, IAT – Short, I-POE, IREQ, PIEUSA, PIUQ, PIUQ-SF-6, PIUQ-SF-9, and YDQ). With a total of 17 validation studies, the IAT was by far the most frequently validated measure, followed by the CIUS (n = 11 studies), GPIUS2 (n = 5 studies), and PIUQ-SF-6 (n = 4 studies). Scales validated by 3 studies were PIUQ and its short version PIUQ-SF-9. The CIAS, IAT – Short, I-POE, IREQ, PIEUSA, and YDQ were validated by 2 studies. The other 19 scales had the lowest evidence base by being validated by only 1 study: CIA-Goldberg, CIA-Young, CIAS-SF, CIAS-R, CIAT, DIA, EIUS, IAS (Original: [59]), IAS (Original [61, 62]:), IAT-A, bIAQ, IDS-15, Initial screening scale, Internet-user Assessment Screen, K-Scale, OCS, PIUS-a, PYDQ, SPIUT (Tables 1, 2, 3, and 1).

Except for 7 studies adopting a dichotomous response format (yes/no) on CIA-Goldberg [35], CIA-Young [35], CIAT [40], IAT [67], I-POE [88], PYDQ [104], and YDQ [106, 107], other tools used Likert rating scales, primarily a 5-point Likert scale.

The minimum mean age for which validation was undertaken was 8.55 years (SD = 2.02) (CIUS [48]). Moreover, some of the instruments presented were developed for adolescents and validated on this young sample, like CIA-Young, IAT-A, PIUESA, and PIUS-a.

A total of 5 short versions of the CIAS, IAT, and PIUQ have been validated in children and adolescents: CIAS-SF, PIUQ-SF-6, PIUQ-SF-9, bIAQ, IAT – Short.

Two instruments standing out from the usual self-reporting questionnaires could be identified: the PYDQ [104], a parental instrument to assess Internet use behavior of their own children, and the DIA [52] consisting of an independent evaluation in the form of a semi-structured interview based on DSM-5.

A second scale based on the DSM-5 criteria was the IDS-15. However, none of the identified tools was based on the ICD-11.

Even though in about half of the studies a cut-off value has been reported (n = 29 studies, 23 tools: CIA-Goldberg [35], CIA-Young [35], CIAS-R [38], CIAS-SF [39•], EIUS [53], GPIUS2 [57], IAS [60], IAS [63], IAT [65, 70, 76, 78,79,80], IAT-A [81], IAT – Short [83], bIAQ [84], Initial screening scale [86], Internet-user Assessment Screen [87], I-POE [89], IREQ [91], K-Scale [92], OCS [93], PIEUSA [95], PIUQ [96, 97], PIUQ-SF-6 [100], PIUQ-SF-9 [97, 102], PIUS-a [103], YDQ [106]), overall, only 2 studies have externally validated the cut-off scores, namely for the CIAS [37] and IAT – Short [83], in which a diagnostic interview was conducted to determine a reliable cut-off value.

Psychometric Findings

In total, internal consistency ranged between α = 0.68 (CIA-Goldberg) [35] to 0.96 (PIUQ) [98], with mostly high reliability scores, since in 51 studies a Cronbach’s alpha higher than 0.80 could be traced (Table 2). Although the length of the scale should be taken into account [108], even the short scales exhibited to be sufficient reliable. By comparison, significantly fewer tools were tested for test–retest reliability (n = 9 tools; n = 11 studies). Here, the IAS showed the highest outcome (r = 0.98, 1 week [60], followed by the CIUS (r = 0.89, 2 weeks [47]).

Questionnaires with the longest test–retest duration were the CIAS-SF (48 months, r = 0.20) [39•], and the IAT (24 months, r = 0.56) [72].

With regard to construct validity, operationalized as relationship between the IUD instrument and other similar or closely related tools, most studies examined the correlation with other screenings on PIU and IUD (range: r = 0.34 (DIA with Internet Addiction Proneness Scale for Adolescents (O_A)) [52] up to r = 0.88 (PIUQ with IAT [98]), using mostly the IAT as a reference tool. The highest convergent validity was found for the PIUQ, which correlated with the IAT at 0.88 [98], and its short versions (PIUQ-SF-9: r = 0.86; PIUQ-SF-6: r = 0.85) [98], followed by the CIUS (r = 0.85 with IAT) [43].

In terms of criterion validity, which was evaluated by examining the association with Internet use behavior (i.e., time spent on Internet activities) and the total score of an instrument, validation studies ranged from 0.19 (CIA-Goldberg) [35] to 0.47 (CIUS) [42].

Furthermore, although a total of 11 studies employed invariance analyses, only 2 tools have been tested for measurement invariance using Rasch analyses, namely the IDS-15 and IAT.

No tools retained in this review have been examined in conjunction with standardized measures of functional impairment. Accordingly, no statement on the clinical significance of IUD can be derived.

Discussion

Validation Frequency and Instruments with the Highest Scoring

The systematic review investigated psychometric properties of a total of 31 survey instruments on PIU and IUD in children and adolescents based on 70 identified empirical studies which were mainly conducted in Europe and Asia. The IAT was the most frequently validated IUD tool, followed by CIUS, GPIUS2, and PIUQ. If the QRG is used as a basis for evaluation, no clear recommendation in favor of a particular tool can be made. With a total score of 10 out of 26 points, the GPIUS2 performed best, followed by CIUS, IAT, and the short form of the PIUQ, PIUQ-SF-6 achieving 9 points (Table 1). If only the individual validation studies are taken into account, i.e., without integrating the evaluations of the individual studies on each instrument (Table 3), the IDS-15 [85] has also achieved quite good results. However, when considering the number of validation studies and the individual findings integrated for a single instrument, the IDS-15 scored only 8 points and is therefore not included in the following recommendation, as further validation studies on this instrument are required.

GPIUS2

The GPIUS2 by Caplan [111] consisting of 15 items and an 8-point Likert scale is based on the cognitive-behavioral model, and hence not referring to DSM or ICD criteria which can be considered a weakness. Furthermore, no data on retest reliability could be identified. A cut-off score has been specified (52 points) [57], though not externally validated. Therefore, it can be used for screening purposes, although an external validation of the cut-off is still pending.

CIUS

With a total of 11 validation studies, the CIUS [109] consisting of 14 items using a 5-point Likert scale was the second most validated tool in young age groups. However, this strength is countered by the disadvantage that the CIUS is based on the DSM-4 criteria for pathological gambling, as well as on the component model of behavioral addiction [110], which are no longer current. In addition, the CIUS has no specified cut-off value for individuals younger than 18 years. Therefore, the CIUS is rather inadvisable for diagnostic purposes in this age group. However, validation studies on this tool relied more frequently on representative, large samples compared to the other scales, which constitutes an advantage. Moreover, also data on test–retest reliability are available [47], in contrast to the IAT and GPIUS2.

IAT

Although the IAT [61] is the most validated tool (17 included studies), this test has some weaknesses, e.g., being based on an older theoretical concept (DSM-4 criteria for pathological gambling) and heterogenous cut-off values, item numbers (10–20 items), and response formats (dichotomous vs. from 3- up to 6-point Likert scale). Only one study so far has evaluated the usefulness of the given cut-off-scores [77]. In addition, validation studies have not tested this tool with regard to retest-validity. Moreover, with a total of 20 items, the IAT might be quite long and thus less economic compared to other instruments. At the same time, only the IDS-15 [85] and IAT [75] have been tested for measurement invariance using Rasch analysis.

Some refinements of the IAT have been undertaken: an adolescent version, IAT-A [81], and 2 short versions, IAT – Short [82, 83], and bIAQ [84]. However, little data is available regarding its modified items, as they have been validated only once so far in younger age groups. External validity has been tested as correlation with other IUD tools, and first data exist regarding the correlation with an external gold standard derived by a clinical interview [83].

PIUQ

The PIUQ by Demetrovics et al. [112] has also been evaluated comparatively often in young age groups, but is not based on an addiction theory model by referring only to the items of the IAT. A further weakness of the PIUQ is its divergent cut-off values which differ between the studies. However, if an economic assessment is desired, the short scales of the PIUQ, PIUQ-SF-9, and PIUQ-SF-6 can be used. It has been shown that, opposed to the relatively low test–retest reliability ranging between 0.54 and 0.56 [98], the internal consistency of the short scales PIUQ-SF-9 and PIUQ-SF-6 showed to be high enough to reliably measure PIU (α = 0.77) [100, 101]. Thus, the short versions of the PIUQ can be recommended due to their simpler manageability which offers users an economical alternative to the long version. Nevertheless, none of the instruments presented above has been validated in clinical samples, so a sound rating of the psychometric quality in clinical contexts is not possible.

PYDQ

As an external rating, the PYDQ extends the view of already established self-report instruments by a parent’s perspective. It appears to be another promising approach overcoming self-assessment, which can be biased by symptom denial [113] or poor introspection skills [114, 115] that could reduce adolescent assessment accuracy [113]. Additionally, the PYDQ is an interesting alternative, especially as parents are often the ones who seek help [104] and might provide a first impression of the PIU of the adolescents. Moreover, some of the items asking about observable behavior are easier for parents to assess than questions concerning the adolescent’s thoughts and feelings [104]. A moderate internal consistency of 0.70 for the PYDQ [104] was measured, which is in the range of the reliability coefficients for the self-assessment version of the YDQ (from α = 0.62 [107] to 0.72 [106]). However, the YDQ exhibited one of the lowest reliability scores compared to the other tools. For future research, comparison with the adolescents' ratings would be of great value to substantiate the construct validity of the PYDQ.

Theoretical Foundation

If the theoretical foundation referring to current DSM-5 criteria for Gaming Disorder is used as an assessment criterion, the instruments IDS-15 and DIA can be recommended. The latter instrument also sounds promising, as it expands the survey formats by providing a supplement to the commonly offered self-report questionnaires. However, further studies on these tools are desirable due to being validated only once so far. Thus, we are unfortunately unable to make a well-founded statement regarding its psychometric quality emphasizing this as a target for future research.

Clinical Validation

In one of the included studies, the DIA classification was verified in clinical practice by including only children and adolescents scoring above the cut-off for behavioral addiction on at least one screening questionnaire (DIA) [52]. In two other studies (CIAS, IAT – Short), a diagnostic interview by psychiatrists, i.e., an independent evaluation, took place [37, 83]. On the basis of the remaining studies, it is impossible to say whether the investigated tools can be used as a valid measure to distinguish between IUD and normal Internet use.

Cut-off Scores

Although about one-third of all survey instruments (n = 29) have specified a cut-off value, only 2 studies undertook an external validation of the tools (CIAS, IAT – Short). In addition, despite reporting cut-off values, some studies did not always explain exactly what this value means or what it refers to exactly. No cut-off value was reported for some of the instruments considered (CIAT, CIUS, DIA, IDS-15, PYDQ, SPIUT), so caution is needed here when classifying IUD vs. normal Internet use [116]. Furthermore, there were sometimes divergent findings between the studies regarding the cut-off value, even within 1 tool. For example, the cut-off value of 29 points [102] given the PIUQ-SF9 to classify PIU was more conservative than the cut-off value of 22 proposed by another study [97]. However, cut-off points are not only important for the purposes of epidemiological research but also to identify individuals who need interventions [117]. It would be helpful to use current clinical criteria and diagnostically accurate cut-off values to better differentiate between IA and normal Internet use enabling the use of already existing tools in clinical contexts [52, 118]. Moreover, longitudinal studies are needed for, among others, examination of the identified cut-off point in predicting behavioral and health outcomes [119]. Overall, identifying problematic users and establishing (clinical) relevant cut-off scores based on an objective gold standard, i.e., diagnostic interview in clinically diagnosed groups of problematic Internet users as validation sample, would be indicated [7•, 116, 117].

Test Refinement

Hardly any of the enclosed tools have been tested for measurement invariance using Rasch analyses, e.g., to assess or whether the items and their underlying construct have the same meaning for adolescents as for adults or for the assessment of cross-national or cultural differences [120]. So far, only the IDS-15 [85] and IAT [75] have been tested for Rasch invariance.

In only about one quarter of the studies (n = 16), validation was based on large, representative samples of children and adolescents. Hence, most validation studies have relied on non-probabilistic samples, so the power of such studies can be considered limited due to the lack of representativeness which comes along with a potential impact of sample-specific influences on our comparisons.

Directions for Future Research

As the majority of tools have only had 1 validation study, it seems that most studies are developing and validating new tools on a one-off basis rather than repeatedly validating existing methods. Thus, further studies on already existing instruments are needed to make a final decision on a recommendation [29, 66, 121]. This would be a first step towards a “gold standard” for the assessment of IUD, which would go hand in hand with a better synthesis of research findings as well as better comparability of test results [66]. A next step in establishing the gold standard for IUD assessment would be a reference to actual theoretical frameworks, like the DSM-5 for IGD.

Another challenge is a discrepancy in labeling and terminology as various synonyms of IUD exist in the literature with different terms such as “pathological Internet use,” “problematic Internet use,” “excessive Internet use,” “Internet dependency,” or “Internet addiction” being often used interchangeably without clear diagnostic differentiation [122]. Furthermore, not all instruments on IUD have been validated in children and adolescents, like for example the Chinese Internet Addiction Inventory [123].

In addition, transparency regarding the sampling approach, a better description of the sample, and in the case of large representative samples, indication for which characteristics this sample is representative would be also desirable for future research, as we had great difficulties with the rating for this criterion in the QRG due to the fact that only little information on this topic has been reported by the validation studies.

As the majority of tools are based on self-report being thus often susceptible to biases such as social desirability or recall bias, the additional use of external ratings by clinicians or relatives may prove useful in assessing whether self-reported symptoms are a good indicator of PIU [102, 104] especially in young age groups.

Finally, future studies should take a closer look at different activities on the Internet, e.g., chatting and streaming, which are associated with different intensity of use [64, 124]. At the same time, consideration should be given to adapting the already established instruments to the constantly changing trends on the Internet. Corresponding questionnaires were partly developed many years ago and might no longer correspond to the current use of language, especially by young people. In addition, the field of Internet use is very dynamic, with new platforms constantly coming onto the market that should be considered and older platforms needing to be reviewed to ensure they are up to date. In the Internet-user Assessment Screen, for instance, rather outdated items like “I often use MSN or ICQ of Blogs” are used [87]. A further example in this context, the IAT assesses with one item the frequency of checking emails, although in the meantime other communication tools such as TikTok and WhatsApp have largely replaced emails and are of higher importance among adolescents [65]. In general, the wording of items should be examined in order to ensure content validity [125].

In addition, the use of more objective measures of online activities, e.g., to assess the actual usage time with the help of apps, could be a useful valid alternative tool to self-report data [33••, 126].

Previous reviews of PIU screening instruments have reported various inconsistencies and psychometric weaknesses [31], which we can confirm based on the data presented: Overall, the quality of the included studies can only be rated as moderate, as studies in our review achieved only a score of 11 (IDS-15, Table 3 which does not yet integrate the rating for a single instrument across all validation studies) and 10 (GIUPS2, Table 1 comprising integrated ratings across studies for each instrument) out of maximal 26 points in the QRG. Therefore, for future research, it would be desirable to improve study quality, besides a clinical validation of existing tools under consideration of functional impairment.

Limitations

Results of our review should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations: First, our research project has not been preregistered beforehand, for instance in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). Secondly, studies presenting only one global value for internal consistency were excluded, which meant that additional reliability values were not considered. Thirdly, studies examining solely divergent validity were not included. Fourthly, a meta-analysis was not conducted, as we assumed considerable heterogeneity in assessment of PIU and IUD. No additional subgroup or sensitivity analyses were conducted either, as these were not in line with our study aims. Lastly, this search was limited to English language studies, thus in a potential omission of relevant but in other languages published literature.

Conclusions

This systematic review offers an overview of the psychometric evidence of existing screening instruments for IUD in the field of young age groups. The IAT was by far the most widely validated measure in our review. On the whole, our review revealed rather inconclusive findings: None of the validated instruments for the survey of PIU has proven to be clearly superior, as strengths in one area are offset by weaknesses in other areas. The GPIUS2 achieved the highest scores, followed by CIUS, IAT, and the short form of the PIUQ: PIUQ-SF-6. When using the reference to the classification systems as a criterium, the DIA and IDS-15 can be used.

Although no final recommendation on a specific screening regarding IUD in childhood and adolescence can be drawn, there are a number of promising scales, especially those scales with one validation study each still need further validation. Moreover, all of the included studies only partially provided psychometric properties as none of them has covered all of our criteria.

As a relatively new research field in the spectrum of addiction, the assessment of IUD would benefit from clear definitions and standardized screening instruments to identify Internet-related harms across the spectrum of maladaptive behavior patterns on the Internet. Further research on the optimization of screening tools and their applicability in large-scale studies as well as a development of future instruments with a clear cut-off-score taking the actual DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria for IGD into account and being validated against a recognized (clinical) gold standard would be required to strengthen the research field on IUD. An expert appraisal by a group of experts in a Delphi process [127] is currently being pursued by our working group in order to develop recommendations regarding screening tools for use within younger population groups [128] to shed further light on this topic.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Poli R. Internet addiction update: diagnostic criteria, assessment and prevalence. Neuropsychiatry. 2017;7(1):4–8. https://doi.org/10.4172/Neuropsychiatry.1000171.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14854.

Dinleyici M, Carman KB, Ozturk E, Sahin-Dagli F. Media use by children, and parents’ views on children’s media usage. Interact J Med Res. 2016;5(2):e18. https://doi.org/10.2196/ijmr.5668.

Hedderson MM, Bekelman TA, Li M, Knapp EA, Palmore M, Dong Y, et al. Trends in screen time use among children during the COVID-19 pandemic, July 2019 through August 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2256157. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.56157.

•• Madigan S, Eirich R, Pador P, McArthur BA, Neville RD. Assessment of changes in child and adolescent screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):1188–98. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.4116A recent meta-analysis on screen time in younger age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bergmann C, Dimitrova N, Alaslani K, Almohammadi A, Alroqi H, Aussems S, et al. Young children’s screen time during the first COVID-19 lockdown in 12 countries. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05840-5.

• Paschke K, Austermann MI, Simon-Kutscher K, Thomasius R. Adolescent gaming and social media usage before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim results of a longitudinal study. SUCHT. 2021;67(1):13–22. https://doi.org/10.1024/0939-5911/a000694Interim results of a longitudinal study providing prevalence rates of problematic gaming and social media use among adolescents according to the ICD-11 criteria.

Griffiths MD. Social networking addiction: emerging themes and issues. J Addict Res. 2013;4(5):e118. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000e118.

Kuss D, Griffiths M. Social networking sites and addiction: ten lessons learned. IJERPH. 2017;14(3):311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311.

Shek DTL, Sun RCF, Yu L. Internet addiction. In: Pfaff DW, editor. Neuroscience in the 21st century [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013 [cited 2023 Apr 11]. p. 2775–811. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4614-1997-6_108.

•• Dieris-Hirche J, Bottel L, Herpertz S, Timmesfeld N, te Wildt BT, Wölfling K, et al. Internet-based self-assessment for symptoms of internet use disorder—impact of gender, social aspects, and symptom severity: German cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e40121. https://doi.org/10.2196/40121Intervention study providing evidence that individuals with IUD can be reached via internet-based eHealth offers.

Peris M, de la Barrera U, Schoeps K, Montoya-Castilla I. Psychological risk factors that predict social networking and internet addiction in adolescents. IJERPH. 2020;17(12):4598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124598.

Arias-de la Torre J, Puigdomenech E, García X, Valderas JM, Eiroa-Orosa FJ, Fernández-Villa T, et al. Relationship between depression and the use of mobile technologies and social media among adolescents: umbrella review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e16388. https://doi.org/10.2196/16388

Ostovar S, Allahyar N, Aminpoor H, Moafian F, Nor MBM, Griffiths MD. Internet addiction and its psychosocial risks (depression, anxiety, stress and loneliness) among Iranian adolescents and young adults: a structural equation model in a cross-sectional study. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2016;14:257–67.

Király O, Potenza MN, Stein DJ, King DL, Hodgins DC, Saunders JB, et al. Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: consensus guidance. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;100:152180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152180.

• Fineberg NA, Menchón JM, Hall N, Dell’Osso B, Brand M, Potenza MN, et al. Advances in problematic usage of the internet research – a narrative review by experts from the European network for problematic usage of the internet. Compr Psychiatry. 2022;118:152346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152346A recent narrative review on the state of the art concerning PIU research including scientific progress and research challenges as well as an overview of working definitions for various PIU-subtypes.

Yu L, Luo T. Social networking addiction among Hong Kong university students: its health consequences and relationships with parenting behaviors. Front Public Health. 2021;8:555990. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.555990.

Müller KW, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, Woelfling K, Beutel ME. Prevalence of internet addiction in the general population: results from a German population-based survey. Behav Inf Technol. 2014;33(7):757–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2013.810778.

Rumpf H-J, Vermulst AA, Bischof A, Kastirke N, Gürtler D, Bischof G, et al. Occurence of internet addiction in a general population sample: a latent class analysis. Eur Addict Res. 2014;20(4):159–66. https://doi.org/10.1159/000354321.

Meng S-Q, Cheng J-L, Li Y-Y, Yang X-Q, Zheng J-W, Chang X-W, et al. Global prevalence of digital addiction in general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;92:102128.

Yao MZ, Zhong Z. Loneliness, social contacts and internet addiction: a cross-lagged panel study. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;30:164–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.08.007.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders [Internet]. fifth edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013 [cited 2021 Sep 22]. Available from: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

World Health Organization. ICD-11—mortality and morbidity statistics [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1448597234

Saunders JB, Hao W, Long J, King DL, Mann K, Fauth-Bühler M, et al. Gaming disorder: its delineation as an important condition for diagnosis, management, and prevention. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(3):271–9. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.039.

Rumpf H-J, Achab S, Billieux J, Bowden-Jones H, Carragher N, Demetrovics Z, et al. Including gaming disorder in the ICD-11: the need to do so from a clinical and public health perspective: commentary on: a weak scientific basis for gaming disorder (van Rooij et al., 2018). J Behav Addict. 2018;7(3):556–61. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.59.

Buctot DB, Kim N, Kim JJ. Factors associated with smartphone addiction prevalence and its predictive capacity for health-related quality of life among Filipino adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;110(1):104758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104758.

Rumpf H-J, Brand M, Wegmann E, Montag C, Müller A, Müller K, et al. Covid-19-Pandemie und Verhaltenssüchte: Neue Herausforderungen für Verhaltens- und Verhältnisprävention. SUCHT. 2020;66(4):212–6. https://doi.org/10.1024/0939-5911/a000672.

Kotyśko M, Michalak M. The scale of excessive use of social networking sites – the psychometric characteristics and validity of a proposed tool. ain. 2020;33(3):239–52. https://doi.org/10.5114/ain.2020.101800.

Laconi S, Rodgers RF, Chabrol H. The measurement of internet addiction: a critical review of existing scales and their psychometric properties. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:190–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.026.

Kuss D, Griffiths M, Karila L, Billieux J. Internet addiction: a systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4026–52. https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990617.

Moreno MA. Problematic internet use among US youth: a systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(9):797–805. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.58.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

•• King DL, Chamberlain SR, Carragher N, Billieux J, Stein D, Mueller K, et al. Screening and assessment tools for gaming disorder: a comprehensive systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;77:101831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101831Systematic review evaluating all available instruments on gaming disorder and their associated empirical evidence base.

Schlossarek S, Schmidt H, Bischof A, Bischof G, Brandt D, Borgwardt S, et al. Psychometric properties of screening instruments for social network use disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(4):419–26. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5741.

Shek DTL, Tang VMY, Lo CY. Internet addiction in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong: assessment, profiles, and psychosocial correlates. Sci World J. 2008;8:776–87. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2008.104.

Columb D, Keegan E, Griffiths MD, O’Gara C. A descriptive pilot survey of behavioural addictions in an adolescent secondary school population in Ireland. Ir J Psychol Med. 2021;1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2021.40

Ko C-H, Yen C-F, Yen C-N, Yen J-Y, Chen C-C, Chen S-H. Screening for internet addiction: an empirical study on cut-off points for the Chen internet addiction scale. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21(12):545–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70206-2.

Mak K-K, Lai C-M, Ko C-H, Chou C, Kim D-I, Watanabe H, et al. Psychometric properties of the revised Chen internet addiction scale (CIAS-R) in Chinese adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(7):1237–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9851-3.

Hsieh Y-P, Hwa H-L, Shen AC-T, Wei H-S, Feng J-Y, Huang C-Y. Ecological predictors and trajectory of internet addiction from childhood through adolescence: a nationally representative longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126253. A recent longitudinal study on trajectories and predictors of Internet addiction across time from childhood to adolescence enrolling a nationally representative sample.

Zhu X, Shek DTL, Chu CKM. Internet addiction and emotional and behavioral maladjustment in Mainland Chinese adolescents: cross-lagged panel analyses. Front Psychol. 2021;12:781036. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781036.

Aonso-Diego G, Postigo Á, Secades-Villa R. Psychometric validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale in Spanish adolescents. Assessment. 2023;10731911231188738.

Dhir A, Chen S, Nieminen M. A repeat cross-sectional analysis of the psychometric properties of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) with adolescents from public and private schools. Comput Educ. 2015;86:172–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.011.

Dhir A, Chen S, Nieminen M. Psychometric validation of the Chinese Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) with Taiwanese high school adolescents. Psychiatr Q. 2015;86(4):581–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9351-9.

Dhir A, Chen S, Nieminen M. Psychometric validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale: relationship with adolescents’ demographics, ICT accessibility, and problematic ICT use. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2016;34(2):197–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315572575.

Jovičić Burić D, Muslić L, Krašić S, Markelić M, Pejnović Franelić I, Musić MS. Croatian validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale. Addict Behav. 2021;119:106921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106921.

Jusienė R, Pakalniškienė V, Wu JC-L, Sebre SB. Compulsive internet use scale for assessment of self-reported problematic internet use in primary school-aged children. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1173585.

Kuzucu Y, Ozdemir Y, Ak S. Psychometric properties of a Turkish version of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale. Eur Sci J. 2015;11:37–47.

Miltuze A, Sebre SB, Martinsone B. Consistent and appropriate parental restrictions mitigating against children’s compulsive internet use: a one-year longitudinal study. Tech Know Learn. 2021;26(4):883–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09472-4.

Ortuño-Sierra J, Pérez-Sáenz J, Mason O, Pérez de Albeniz A, Fonseca Pedrero E. Problematic internet use among adolescents: Spanish validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS). Adicciones [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 11]; Available from: https://adicciones.es/index.php/adicciones/article/view/1801

Wartberg L, Petersen K-U, Kammerl R, Rosenkranz M, Thomasius R. Psychometric validation of a German version of the compulsive internet use scale. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(2):99–103. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0689.

Van Zalk N. Social anxiety moderates the links between excessive chatting and compulsive Internet use. Cyberpsychology: J Psychosoc Res Cyberspace. 2016;10(3):3. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2016-3-3.

Ryu H, Lee JY, Choi AR, Chung SJ, Park M, Bhang S-Y, et al. Application of diagnostic interview for internet addiction (DIA) in clinical practice for Korean adolescents. J Clin Med. 2019;8(2):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8020202.

Škařupová K, Ólafsson K, Blinka L. Excessive internet use and its association with negative experiences: quasi-validation of a short scale in 25 European countries. Comput Human Behav. 2015;53:118–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.047.

Fioravanti G, Primi C, Casale S. Psychometric evaluation of the generalized problematic internet use scale 2 in an Italian sample. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16(10):761–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0429.

Gámez-Guadix M, Orue I, Calvete E. Evaluation of the cognitive-behavioral model of generalized and problematic internet use in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema. 2013;25(3):299–306. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2012.274.

Gámez-Guadix M, Villa-George FI, Calvete E. Measurement and analysis of the cognitive-behavioral model of generalized problematic internet use among Mexican adolescents. J Adolesc. 2012;35(6):1581–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.005.

Machimbarrena JM, González-Cabrera J, Ortega-Barón J, Beranuy-Fargues M, Álvarez-Bardón A, Tejero B. Profiles of problematic internet use and its impact on adolescents’ health-related quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(20):3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203877.

Marzo JC, García-Oliva C, Piqueras JA. Factorial analysis and gender invariance of GPIUS2 scale and evaluation of Caplan’s cognitive-behavioral model of problematic internet use in adolescents. An psicol. 2022;38(3):469–77. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.508461.

Nichols LA, Nicki R. Development of a psychometrically sound internet addiction scale: a preliminary step. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18(4):381–4. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.381.

Canan F, Ataoglu A, Nichols LA, Yildirim T, Ozturk O. Evaluation of psychometric properties of the internet addiction scale in a sample of Turkish high school students. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(3):317–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0160.

Young KS. Caught in the net: how to recognize the signs of Internet addiction–and a winning strategy for recovery. New York: J. Wiley; 1998.

Young KS. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1(3):237–44. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237.

Sung M, Shin Y-M, Cho S-M. Factor structure of the internet addiction scale and its associations with psychiatric symptoms for Korean adolescents. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(5):612–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-013-9689-0.

Baggio S, Iglesias K, Berchtold A, Suris J-C. Measuring internet use: comparisons of different assessments and with internet addiction. Addict Res Theory. 2017;25(2):114–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2016.1206083.

Černja I, Vejmelka L, Rajter M. Internet addiction test: Croatian preliminary study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):388. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2366-2.

Dhir A, Chen S, Nieminen M. Psychometric validation of internet addiction test with Indian adolescents. J Educ Comput Res. 2015;53(1):15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633115597491.

Dou D, Shek DTL. Concurrent and longitudinal relationships between positive youth development attributes and adolescent internet addiction symptoms in Chinese Mainland high school students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041937.

Fioravanti G, Casale S. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Italian internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18(2):120–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0493.

Hawi NS. Arabic validation of the internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16(3):200–4. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0426.

Lai C-M, Mak K-K, Watanabe H, Ang RP, Pang JS, Ho RCM. Psychometric properties of the internet addiction test in Chinese adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(7):794–807. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst022.

Lai C-M, Mak K-K, Cheng C, Watanabe H, Nomachi S, Bahar N, et al. Measurement invariance of the internet addiction test among Hong Kong, Japanese, and Malaysian adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18(10):609–17. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0069.

Lai W, Wang W, Li X, Wang H, Lu C, Guo L. Longitudinal associations between problematic Internet use, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(7):1273–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01944-5.

Li G. Hierarchical linear model of internet addiction and associated risk factors in Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14008. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114008.

Mishra A, Shrivastava P, Kumar M. Assessing the psychometric properties of the internet addiction test (IAT) among Indian school students. Natl J Community Med. 2023;14:485–90.

Panayides P, Walker MJ. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the internet addiction test (IAT) in a sample of Cypriot high school students: the Rasch measurement perspective. Eur J Psychol. 2012;8(3):327–51. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v8i3.474.

Siste K, Suwartono C, Nasrun MW, Bardosono S, Sekartini R, Pandelaki J, et al. Validation study of the Indonesian internet addiction test among adolescents. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0245833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245833.

Stavropoulos V, Alexandraki K, Motti-Stefanidi F. Recognizing internet addiction: prevalence and relationship to academic achievement in adolescents enrolled in urban and rural Greek high schools. J Adolesc. 2013;36(3):565–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.008.

Tsermentseli S, Karipidis N, Samaras P, Thompson T. Assessing the factorial structure of the internet addiction test in a sample of Greek adolescents. Hell J Psychol. 2018;15:274–88.

Watters CA, Keefer KV, Kloosterman PH, Summerfeldt LJ, Parker JDA. Examining the structure of the internet addiction test in adolescents: a bifactor approach. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(6):2294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.020.

Yaffe Y, Seroussi D-E. Further evidence for the pychometric properties of Young’s internet addiction test (IAT): a study on a sample of Israeli-Arab male adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(6):1030–9. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.43.6.2.

Teo T, Kam C. Validity of the internet addiction test for adolescents and older children (IAT-A): tests of measurement invariance and latent mean differences. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2014;32(7):624–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428291453170.

Evli M, Şimşek N, Işıkgöz M, Öztürk Hİ. Internet addiction, insomnia, and violence tendency in adolescents. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2023;69(2):351–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640221090964.

Tateno M, Horie K, Shirasaka T, Nanba K, Shiraishi E, Tateno Y, et al. Clinical usefulness of a short version of the internet addiction test to screen for probable internet addiction in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. IJERPH. 2023;20:4670.

Gamito PS, Morais DG, Oliveira JG, Brito R, Rosa PJ, de Matos MG. Frequency is not enough: patterns of use associated with risk of internet addiction in Portuguese adolescents. Comput Human Behav. 2016;58:471–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.013.

Lin C-Y, Ganji M, Pontes HM, Imani V, Broström A, Griffiths MD, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Persian internet disorder scale among adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2018;7(3):665–75. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.88.

Gómez Salgado P, Rial Boubeta A, Braña TT. Evaluation and early detection of problematic internet use in adolescents. Psicothema. 2014;26(1):21–6. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.109.

Chow SL, Leung GM, Ng C, Yu E. A screen for identifying maladaptive internet use. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2008;7(2):324–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-008-9170-4.

Opsenica-Kostić J, Pedović I, Panić T. Problematic internet use among adolescents: psychometric properties of the index of problematic online experiences (I-POE). Temida. 2018;21(2):207–27. https://doi.org/10.2298/TEM1802207O.

Mitchell KJ, Jones LM, Wells M. Testing the index of problematic online experiences (I-POE) with a national sample of adolescents. J Adolesc. 2013;36(6):1153–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.09.004.

Casas JA, Ruiz-Olivares R, Ortega-Ruiz R. Validation of the internet and social networking experiences questionnaire in Spanish adolescents. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2013;13(1):40–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1697-2600(13)70006-1.

Servidio R, Bartolo MG, Palermiti AL, Casas JA, Ruiz RO, Costabile A. Internet addiction, self-esteem and the validation of the Italian version of the internet related experiences questionnaire. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 2019;69:51–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2019.03.003.

Mak K-K, Nam JK, Kim D, Aum N, Choi J-S, Cheng C, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Korean scale for internet addiction (K-Scale) in Japanese high school students. Psychiatry Res. 2017;249:343–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.044.

Floros G, Siomos K. Patterns of choices on video game genres and internet addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15(8):417–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0064.

Lopez-Fernandez O, Freixa-Blanxart M, Honrubia-Serrano ML. The problematic internet entertainment use scale for adolescents: prevalence of problem internet use in Spanish high school students. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;16(2):108–18. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0250.

Lopez-Fernandez O, Honrubia-Serrano ML, Gibson W, Griffiths MD. Problematic internet use in British adolescents: an exploration of the addictive symptomatology. Comput Human Behav. 2014;35:224–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.042.

El Asam A, Samara M, Terry P. Problematic internet use and mental health among British children and adolescents. Addict Behav. 2019;90:428–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.007.

Koronczai B, Urbán R, Kökönyei G, Paksi B, Papp K, Kun B, et al. Confirmation of the three-factor model of problematic internet use on off-line adolescent and adult samples. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(11):657–64. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0345.

Lin M, Kim Y. The reliability and validity of the 18-item long form and two short forms of the problematic internet use questionnaire in three Japanese samples. Addict Behav. 2020;101:105961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.019.

Aivali P, Efthymiou V, Tsitsika AK, Vlachakis D, Chrousos GP, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, et al. Validation of the Greek version of the problematic internet use questionnaire - short form (PIUQ-SF-6). EMBnet J. 2021;26:e978. https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.26.1.978.

Demetrovics Z, Király O, Koronczai B, Griffiths MD, Nagygyörgy K, Elekes Z, et al. Psychometric properties of the problematic internet use questionnaire short-form (PIUQ-SF-6) in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0159409. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159409.

Opakunle T, Aloba O, Opakunle O, Eegunranti B. Problematic internet use questionnaire-short form-6 (PIUQ-SF-6): dimensionality, validity, reliability, measurement invariance and mean differences across genders and age categories among Nigerian adolescents. Int J Ment Health. 2020;49(3):229–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2020.1776457.

Li W, Diez SL, Zhao Q. Exploring problematic internet use among non-latinx black and latinx youth using the problematic internet use questionnaire-short form (PIUQ-SF). Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:322–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.048.

Rial Boubeta A, Gómez Salgado P, Isorna Folgar M, Araujo Gallego M, Varela MJ. PIUS-a: problematic internet use scale in adolescents. Dev Psychometric Validation Adicciones. 2015;27(1):47–63.

Wartberg L, Kriston L, Kegel K, Thomasius R. Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Young diagnostic questionnaire (YDQ) for parental assessment of adolescent problematic internet use. J Behav Addict. 2016;5(2):311–7. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.049.

Siciliano V, Bastiani L, Mezzasalma L, Thanki D, Curzio O, Molinaro S. Validation of a new short problematic internet use test in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. Comput Human Behav. 2015;45:177–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.097.

Siomos KE, Dafouli ED, Braimiotis DA, Mouzas OD, Angelopoulos NV. Internet addiction among Greek adolescent students. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(6):653–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0088.

Wartberg L, Durkee T, Kriston L, Parzer P, Fischer-Waldschmidt G, Resch F, et al. Psychometric properties of a German version of the Young diagnostic questionnaire (YDQ) in two independent samples of adolescents. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2017;15(1):182–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9654-6.

Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284.

Meerkerk G-J, Van Den Eijnden RJJM, Vermulst AA, Garretsen HFL. The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181.

Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use. 2005;10(4):191–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Caplan SE. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: a two-step approach. Comput Human Behav. 2010;26(5):1089–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012.

Demetrovics Z, Szeredi B, Rózsa S. The three-factor model of internet addiction: the development of the problematic internet use questionnaire. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(2):563–74. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.2.563.

Austermann MI, Thomasius R, Paschke K. Assessing problematic social media use in adolescents by parental ratings: development and validation of the social media disorder scale for parents (SMDS-P). JCM. 2021;10(4):617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10040617.

Weil LG, Fleming SM, Dumontheil I, Kilford EJ, Weil RS, Rees G, et al. T The development of metacognitive ability in adolescence. Conscious Cogn. 2013;22(1):264–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.01.004.

Zhou Z, Zhou H, Zhu H. Working memory, executive function and impulsivity in Internet-addictive disorders: a comparison with pathological gambling. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2016;28(2):92–100. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2015.54.

Pontes HM, Andreassen CS, Griffiths MD. Portuguese validation of the Bergen facebook addiction scale: an empirical study. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2016;14(6):1062–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9694-y.

Li J-B, Wu AMS, Feng L-F, Deng Y, Li J-H, Chen Y-X, et al. Classification of probable online social networking addiction: a latent profile analysis from a large-scale survey among Chinese adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2020;9(3):698–708. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00047.

Kuss DJ, van Rooij AJ, Shorter GW, Griffiths MD, van de Mheen D. Internet addiction in adolescents: prevalence and risk factors. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(5):1987–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.002.

Longobardi C, Settanni M, Fabris MA, Marengo D. Follow or be followed: exploring the links between Instagram popularity, social media addiction, cyber victimization, and subjective happiness in Italian adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;113:104955.

Marino C, Vieno A, Altoè G, Spada MM. Factorial validity of the problematic facebook use scale for adolescents and young adults. J Behav Addict. 2016;6(1):5–10. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.004.

Watson JC, Prosek EA, Giordano AL. Investigating psychometric properties of social media addiction measures among adolescents. J Couns Dev. 2020;98(4):458–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12347.

Kelley KJ, Gruber EM. Psychometric properties of the problematic internet use questionnaire. Comput Human Behav. 2010;26(6):1838–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.018.

Huang Z, Wang M, Qian M, Zhong J, Tao R. Chinese internet addiction inventory: developing a measure of problematic internet use for Chinese college students. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10(6):805–12. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9950.

Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, et al. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839.

Schmidt H, Brandt D, Bischof A, Heidbrink S, Bischof G, Borgwardt S, et al. Think-aloud analysis of commonly used screening instruments for Internet use disorders: the CIUS, the IGDT-10, and the BSMAS. J Behav Addict. 2022;11(2):467–80. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00034.

Camerini A-L, Gerosa T, Marciano L. Predicting problematic smartphone use over time in adolescence: a latent class regression analysis of online and offline activities. New Media Soc. 2021;23(11):3229–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820948809.

Jones J, Hunter D. Qualitative research: consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376.

Schlossarek S, Jörren H, Timmermann P, Billieux J, Orsolya K, King DL, et al. MIST - Delphi study: screening measures on internet use disorders in children and adolescents - a Delphi study within the media impact screening toolkit (MIST) workgroup of children and screens [Internet]. 2022. Available from: osf.io/xz6wa

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was conducted as part of the “Intervening with Problematic Internet Use – Preventive Measures for Risk Groups (iPIN)” [Intervenieren bei problematischer Internetnutzung – Präventive Maßnahmen bei Risikogruppen (iPIN)] project and was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (BMG) (ZMVI1-2517DSM210). The funders had no role in the study design and administration, data analysis or interpretation, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. This study was conducted as part of the Media Impact Screening Toolkit (MIST) Workgroup of Children & Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS: writing of the manuscript draft, study concept and design of the review, conduction of the literature searches, study selection, provided summaries of the identified content (Tables 1 and 2), first rater of the quick reference guide (Tables 3 and 1). LH: study selection, second rater of the quick reference guide (Tables 3 and 1). HS: study concept und design, conceptual support and revision of the manuscript. AB: study concept and design, conceptual support and revision of the manuscript. GB: study concept and design, conceptual support and revision of the manuscript. DB: study concept and design, conceptual support and revision of the manuscript. SB: conceptual support and revision of the manuscript. DTB: contributed to the final version of the manuscript. DC: contributed to the final version of the manuscript. PH: contributed to the final version of the manuscript. ZD: contributed to the final version of the manuscript. HJR: study concept and design, grant acquisition, obtained systematic review. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

N/A (not applicable).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 187 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schlossarek, S., Hohls, L., Schmidt, H. et al. Which Are the Optimal Screening Tools for Internet Use Disorder in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review of Psychometric Evidence. Curr Addict Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00568-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00568-w