Abstract

Purpose of Review

Social media offer gambling operators an attractive channel for connecting with gamblers and promoting their products. The aim of the present study is to review the recent literature to summarise the latest findings on marketing strategies of gambling operators, and their effects, with particular focus on social media.

Recent Findings

A systematic review on gambling advertising in social media has been conducted, taking into account English-language journal articles from 2021 onwards, which include primary data collection. Searching three data bases, a total number of 12 studies from peer-reviewed journals were identified. Gambling advertising has an enormous reach, including esports sponsorship and a surge in popularity on streaming platforms, which raises concerns about the protection of gamblers in general and of vulnerable groups in particular. The studies identify individual advertising strategies and investigate the influence of incentives and tips on gambling behaviour. Gaps in the current literature include evidence from certain regions or countries, research into communication strategies on individual social media platforms, and questions about the effectiveness of regulatory measures regarding gambling advertising.

Summary

Gambling operators flexibly adapt their advertising strategies to the surrounding conditions. This appears to be problematic, as the intensity and complexity of gambling advertising increases at the same time as the boundaries between advertising and seemingly neutral content blur. Vulnerable groups, especially children and adolescents, are at special risk, because advertising on social media is particularly attractive for them, while protection mechanisms such as age limits are often missing or being ignored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advertising for gambling on social media is one of the most pressing topics that gambling regulators need to address. Social media are highly attractive for gambling companies as a low-cost alternative or supplement to “traditional” advertising [1]. The immediacy, entertaining qualities and especially the possibilities for interaction account for the special appeal of social media [2]. These characteristics pose high demands on regulators as they need to create a level playing field for advertising in different channels, thus preventing companies from moving to new and less regulated platforms [1]. As regulators often lag behind actual industry developments, they fall short of user expectations who presume a comprehensive protection through regulation [3]. Additionally, wording in legislation documentation is often very general (e.g. “advertising must not be excessive”,Footnote 1 “advertising for public gambling that makes gambling appear to be a commodity of everyday life is not permitted”Footnote 2), which might be useful when addressing constantly changing marketing strategies and features, but complicates practical application. On the other hand, the scientific evidence that regulation should be based on is also fragmentary.

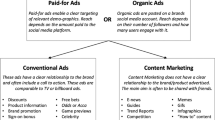

Another difficulty lies in the subject itself: Gambling advertising is not always evident as such, especially on social media. Whereas banners or pop-ups are fairly easy to identify, the borders start to blur in the case of affiliates, influencers and brand ambassadors, and are almost or completely unrecognizable when advertising appears in the shape of user-generated content. The “opacity of commercial peer-to-peer advertising” has been acknowledged to be a particularly sensitive issue (together with “unethical placement of targeted advertising through online profiling” [4]). These less obtrusive forms of marketing seem to be particularly effective: Content marketing (i.e. content not necessarily related to the product or brand) has been shown to be especially appealing to 11-to-24-year olds [5]. This is in line with the finding that advertising has higher effects on vulnerable groups, e.g. on persons with gambling disorder [6]. Consequently, these forms of advertising need major attention.

Aim of the Study

A rapidly changing landscape as well as ongoing regulatory adjustments make it necessary to continuously examine the latest findings on gambling advertising, social media marketing strategies and their effects. To the authors of the present article, five previous reviews were known, among them three systematic [1, 7, 8], one rapid [2] and one narrative review [5]. These reviews suggest that gambling advertising on social media is heavily centred around sports [1, 2, 8]. Such a close association is likely to contribute to the normalisation of gambling [1, 5]. Young people [1, 7] and particularly children [5, 8] could be at particular risk of harm, as well as people with gambling disorder [8]. An area that the authors would like to see analysed more closely includes digital marketing strategies and their effects [1, 2, 7], preferably without relying solely on self-report data [2, 8]. Also, evidence from countries other than the UK or Australia could contribute to a better understanding [2].

Starting from this basis, the present review puts particular focus on the following research questions:

-

i.

What are the attributes of gambling advertising on social media platforms in terms of their frequency, content, and user involvement? Are there differences between individual jurisdictions?

-

ii.

What are the effects of gambling advertising and gambling operators' marketing strategies on users’ attitudes and behaviour?

-

iii.

What safeguards are being put in place to protect people, especially vulnerable groups such as children, adolescents or people with a gambling disorder, from gambling harm?

-

iv.

What are the current research gaps in the area of gambling advertising, taking into account methodological and content-related aspects, and what should be prioritised in future studies?

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines [9], a systematic review was conducted. The search strategy consisted in a combination of terms for social media (including social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, Twitch, YouTube, Weibo, and WeChat) with terms for gambling advertising and gambling marketing (see Appendix). The * operator was used to include all variations of the initial terms. Synonyms of the initial terms were also included in the search string, as in the previous reviews. In addition, the proper names of social networks were explicitly included to identify studies that did not use generic terms in their title or abstract, in order to identify the widest possible range of literature. The final string used the Boolean operators (AND/OR). The terms were searched for in the title, abstract, and keywords. Three databases were searched: Business Source Premiere, Scopus and PubMed. All searches were conducted on August 22nd, 2023, yielding a total number of 1,735 record (see Fig. 1).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Only publications from the beginning of 2021 onwards were considered to avoid overlapping with results from previous reviews [1, 2, 5, 7, 8]. The records needed to contain some form of primary data collection to ensure that the current state of research on gambling advertising on social media was reflected. Records that were not journal articles, such as commentaries, or reviews were not included. Papers written in languages other than English and duplicates were also excluded. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

Identification and Screening

As a first step, records on the topic of gambling advertising on social media were identified using the search string shown in the appendix. Using the filter functions of the databases, of the 1,735 records found, 1,199 publications were removed because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1), mostly because of their early publication date (n = 1,018). One hundred forty-four records were rejected because the document type did not meet the requirement of being classified as journal article. Another five records were discarded because they were in languages other than English. Bibliographic information of the records was extracted from the databases and stored in lists. Furthermore, 27 duplicates resulting from the three different data bases were excluded based on congruent author and title of the record. Finally, the previous reviews (n = 5) were excluded, leaving 536 publications for screening.

The titles and (where necessary) abstracts of the records were screened by two reviewers (AW and JS). The reviewers met regularly to discuss their individual decisions. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus among the reviewers, and together with the third author (SO). In this process, another 510 records were excluded for being off-topic or not containing primary research. Of the remaining 26 records, one publication was not available. Consequently, 25 records were retrieved for full text screening. Twelve more publications were found to be off-topic and one publication lacked primary data.

Search Results

A final set of 12 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. As shown in Table 2, six studies used web scraping to analyse data from social networks [10••, 11•, 12•, 13•, 14•, 15•], of which one study looked at the collected data descriptively [15•]. In addition, three studies conducted qualitative analysis [11•, 12•, 14•], and one study used natural language processing (NLP) methods to analyse the collected data [13•]. One study used a combination of mixed-methods and NLP [10••]. Furthermore, two studies used an observational design [16•, 17••], with one study combining this with a survey [17••]. There are also three studies that use surveys [18••, 19••, 20•]. In addition, one study conducted an online experiment [21•]. The studies were conducted in 7 different jurisdictions, namely the UK (n = 4) [15•, 16•, 18••, 21•], Spain (n = 2) [13•, 20•], Australia (n = 2) [11•, 19••], Germany (n = 1) [10••], France (n = 1) [17••] and simultaneously in Finland and Sweden (n = 2) [12•, 14•]. The included studies can be grouped into three overarching themes according to the research objectives of the systematic review: (1) advertising strategies of gambling operators on social media (n = 6) [10••, 12•, 13•, 14•, 15•, 16•]; (2) effects of gambling advertising on social media (n = 5) [11•, 17••, 18••, 19••, 20•]; and (3) effects of responsible gambling messages (n = 1) [21•].

Results

Twelve publications matching the above outlined criteria were found (see Table 2). Given the short period of time covered by the search, this is a substantial leap in number—previous reviews had identified between 21 [1] and 46 [8] publications, although covering much longer periods of time (between five years [2] and no time limit [7]).

Gambling Advertising on Social Media: Frequency, Content and User Involvement

Several publications examine the volume and frequency of gambling advertising on social media. Studies on gambling advertising on YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram in Finland and Sweden [12•] and on Twitter in Germany [10••] and in Spain [13•] show a high volume of messages, although at much lower levels than e.g. in the UK.

To attract new customers, gambling companies seem to regard esports events as an attractive advertising opportunity. Biggar et al. [15•] examined the sponsorship agreements of popular esports titles during the League of Legends World Championship in 2021. The sponsorship deals enabled gambling companies to reach at least tens of millions of followers on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.Footnote 3 Due to the high share of young men, these followers are particularly interesting as potential future gamblers.

With respect to content, advertising is often linked to seemingly neutral information. Indeed, the most common way of addressing followers on Twitter seems to be by content marketing, as it was found to account for the largest part of the messages. 44 percent of the Finnish and 58 percent of the Swedish posts investigated by Lindeman et al. [12•] were found to be free of “actual references or visual portrayals of gambling activities” (p. 47–48). In their content analysis, Singer et al. [10••] coded a third of the Twitter messages as “news”, i.e. messages informing on sports-related “facts” rather than gambling-related issues.

Although interactive features have been identified as one of the key features of digital marketing, they do not yet seem to play such an important role, or at least not in all jurisdictions. Reactions or comments to posts and likes were rare in Finland, Sweden and Germany [10••, 12•], with the exception of very few posts that attracted tens of thousands of reactions (in Finland and Sweden). In Sweden, operators’ efforts to make users react by polls or by answering a question rose to more than 50% of all posts in 2020 but played minor roles in Finland or Germany. Only the use of hashtags was widespread, as they could be found in most Finnish and Swedish messages. The hashtags used in German tweets related mostly to “factual” information other than the gambling companies themselves or their offers [10••].

Although responsible gambling messages played a minor role in terms of frequency [1], their use was found to assist in the creation of a positive corporate image. In this way, gambling companies were able to portray themselves as responsible and reliable entities, and present gambling as a recreational activity like any other. Such image cultivation could be particularly important in state monopolies, owing to the need to justify and defend market limitations, which is difficult to achieve without public support [14•].Footnote 4 In addition, responsible gambling messages can contribute to the sheer volume of messages when there are no other messages at hand, as shown by the case of an Australian operator who sent messages about responsible gambling only during the lockdown period [11•].

Effects of Gambling Advertising on Social Media

Several studies address the question of advertising efficiency. A coincidence between the expenditures for advertising and gambling activities was found by Critchlow et al. [16•]: Reduced spendings on advertising in the UK during the first lockdown corresponded with self-reported reduction in gambling during the same time period; although the reasons might be ambiguous due to the special circumstances during the pandemic.

Noble et al. [19••] found a significant association between the exposure to online gambling ads and gambling among Australian students. In their study, no other advertising type could be associated with gambling behaviours. Moreover, increased exposure to online gambling ads coincided with a higher probability of at-risk or problem gambling.

Gambling advertising could also induce gamblers to spend more money than planned. Combining data from two British non-probability online surveys, Wardle et al. [18••] found that about 30 percent of current gamblers reported unplanned gambling expenditures after having seen a gambling advert, promotion or sponsorship [18••]. The association appeared after having received a single form of direct marketing or following a sole gambling brand on social media, and was stronger for persons with gambling problems.

While most studies rely on self-report data, Balem et al. [17••] use tracking data provided by the French national gambling authority and the national lottery to investigate the effects of wagering inducements. Frequent use of these inducements, the authors found, was associated with increased gambling frequency and intensity. Again, the effect was stronger for at-risk gamblers.

The online survey undertaken by Gonzálvez-Vallés et al. [20•] found tipsters to be particularly influential. The authors identified a very strong correlation between bets placed owing to the advice of tipsters and the amount of money wagered. Their student respondents also saw a connection between gambling disorder and the influence of tipsters.

Effects of Responsible Gambling Messages

Several studies have looked at whether gambling operators on social media are also promoting the dangers of gambling as part of their advertising strategies. It is shown that responsible gambling content hardly plays a role for communication on Twitter in Spain [13•], Germany [10••] and once more for Australia [11•]. Apparently, its frequency of use is connected to the regulation in force, which is shown by the sudden leap of posts in Sweden after a change in law whereas during the same time period, the volume remained stable for the Finnish monopolist Veikkaus [12•]. The use of responsible gambling messages seems to have dual benefit for gambling operators: Besides compliance with the laws, they assist in the creation of a positive corporate image [14•] and contribute to the sheer volume of messages when there are no other messages at hand [11•].

On the other hand, one study even questions the efficacy of responsible gambling messages [21•]: UK’s most common safer gambling message “when the fun stops, stop”, which is said to have “helped over 5 m adults approaching gambling more responsible” by the company who developed the campaign,Footnote 5 is not found to have any protective effects on the participants in a randomised experiment.

Research Gaps

In addition to the research findings, the literature reviewed also provides an analysis of current research gaps, with various recommendations for future research. For example, there is a lack of work on sponsorship and the development of brand partnerships by gambling operators in the esports sector [15•]. Despite initial findings, there is a need for long-term research into the relationship between gambling and esports, and for as many esports titles as possible to be analysed as comprehensively as possible.

Due to the established selection criteria, most of the studies were conducted during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Some studies point to this fact and indicate that the findings should be understood in the light of this situation [10••, 11•, 12•, 14•, 16•, 18••]. A study from Australia points to the possibility that future research could compare the analysed data between the different lockdown phases [16•]. This could determine the extent to which there is a correlation between increased advertising expenditure and an increase in gambling. In addition, three studies that have looked at the advertising strategies of gambling providers on social media [10••, 12•, 13•] emphasise the need to examine both the extent of this content and the effects on vulnerable people, especially children, young people and gamblers with a gambling disorder, more closely and in the long term.

With regard to the effects of gambling advertising, further differentiation is needed as to exactly which products or incentives lead to more problem gambling [17••, 20•]. The same applies to the time of betting or the amount of the bet [20•]. The environment could also be analysed to determine the impact of gambling advertising [17••] and the involvement of different age groups or generations [20•]. It is also proposed to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the impact of gambling advertising [11•].

Two studies explicitly address the methodological perspective and suggest that future studies should use longitudinal research designs to investigate the long-term effects of gambling advertising [18••, 19••]. This would, in turn, allow comparisons to be made between the closure phases and the post-pandemic period [18••]. Also conclusions could be drawn as to whether a reduction in terrestrial gambling has an impact on the number of people with a gambling disorder and could possibly be classified as a harm-reduction measure. As some studies use self-report data [21•], the authors generally point out that other research designs, such as longitudinal designs, are needed to overcome the known limitations [21•].

Discussion

Gambling Advertising on Social Media: Frequency, Content and User Involvement

For gambling operators, social media are an attractive advertising platform to reach users directly, regardless of place and time, all around the globe and at comparatively low cost [2]. Their aim is to attract potential customers and retain existing ones [22]. Biggar et al. [15•] show how gambling companies access potential client groups—young, male, with gambling affinity—through the sponsorship of esports titles, which might also assist in the convergence of gaming and gambling [23, 24] as well as contribute to the normalisation of gambling [25, 26]. Visibility is increased even further whenever the teams’ athletes appear on livestreaming platforms such as Twitch. Twitch has been criticised for not having any age restrictions or other protective measures in their streaming service [27].

Both the wide use of content marketing and the employment of responsible gambling messages as an image-enhancing strategy make the boundaries between advertising and “factual” information blur, giving cause for concern about the protection of vulnerable groups. Content marketing is often seen as humorous and harmless and therefore especially appealing to children and young adults, who are not yet able to effectively identify advertising contents [5], and thus contributes to the normalisation of gambling [24]. Additionally, the use of positive emotions and sentiment as well as humorous content have been shown to be of particular appeal to children and young people [5]. As vulnerable groups are at specific risk from gambling advertising [28], future research should explore the extent to which children and young people are exposed to gambling advertising on social media. Alternative research designs can help overcome the limitations regarding self-reporting without breaching ethical conventions (e.g. [29]).

Effects of Gambling Advertising on Social Media

The studies identified in this review contribute substantially to the growing body of research on the effect of gambling advertising, both in terms of the general effects of gambling advertising and the effects of individual advertising strategies. These findings could contribute to a taxonomy of advertising strategies and their effects, which is needed all the more because harm for consumers could manifest quickly [30]. Such a taxonomy could form an adequate basis for legislative bodies and authorities to react and take appropriate action.

Effects of Responsible Gambling Messages

Studies from Spain [13•], Germany [10••] and Australia [11•] show that responsible gambling messages play only a minor role in the communication of gambling operators on social media. The use of such messages is often based on the regulation in force [12•], although this can be problematic if the legislation is imprecise. For example, in Germany, the legislator states that “advertising must not be excessiveFootnote 6”, but this is not further defined. Shortcomings in the protection of minors were also identified [10••, 12•], as the marketing of gambling services in all three countries observed (Finland, Germany and Sweden) was accessible to persons under the age of 18. These findings are remarkably alarming as children and young people are particularly vulnerable to gambling and, as the example of sports betting operators in the UK shows [5], find this content particularly appealing.

Even when responsible gambling messages are used in operators’ communications, their purpose tends to be to create a positive corporate image [14•] or simply to increase the number of posts in order to attract more attention in the social networks [11•]. Moreover, the effectiveness of these responsible gambling messages is questionable [31], as the example of “when the fun stops, stop” messages confirms [21•]. As responsible gambling messages are one of the few safeguards used by gambling and social media companies [7], these results are exceptionally worrying.

Research Gaps

The 12 studies reviewed have filled some existing research gaps, such as the lack of studies from countries other than Australia and the UK [2, 8]. Several studies focusing on the advertising strategies of gambling operators used on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and YouTube now feature Germany [10••], Spain [13•] and Finland and Sweden [12•, 14•] (besides Australia and the UK).

But there is still a need for more research in this area, as vulnerable groups are at particular risk from gambling advertising [28]. Future research should explore the extent to which children and young people are exposed to gambling advertising on social media. Alternative research designs can help to overcome the limitations of self-report, for example longitudinal observational study designs combined with the use of tracking data, as shown in a study from France [17••]. Longitudinal research approaches in different countries can serve as a useful extension of existing evidence, investigating which groups of people are particularly affected by gambling advertising and which forms of advertising have the strongest impact. In addition, longitudinal study designs also provide an opportunity to identify long-term marketing trends and advertising strategies.

Machine learning methods offer a further possibility for future research, as the studies from Spain [13•] and Germany [10••] have shown. Appropriate models can be used to analyse not only large amounts of text, but also images, sounds and videos, which, alongside text, are the central content in social networks for conveying content and information [7], especially on Instagram or (more recently) TikTok.

A common challenge in analysing data from social networks is the lack of precise data on who is actually consuming the content. This makes it particularly difficult to monitor personalised marketing, as content changes depending on who is being targeted [7].

Finally, future research should place a stronger focus on the connection between gambling and esports [15•], explicitly on the convergence of gaming and gambling [30]. A more comprehensive picture is needed because harm for consumers could manifest quickly. One such topic could be the role of online communities [32], as these form an inherent part of the lifestyle of younger generations.

Conclusions

The present study illustrates the growing importance of social media in the advertising strategies of gambling operators. Operators flexibly adapt how to approach customers according to the respective circumstances. This is particularly problematic as the intensity and complexity of gambling advertising increases, and the boundaries between advertising and neutral content blur. Vulnerable groups, especially children and young people, are at increased risk, as the current forms of advertising have been shown to be of particular appeal to them. Moreover, the rapid developments imply that regulators will have a hard time keeping up.

Further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the specific characteristics of gambling advertising on different social networks and to investigate the extent to which children and adolescents are exposed. Longitudinal research approaches or forms of machine learning can be useful complements to existing research methods, providing more robust evidence for regulators, who need to minimise potential harm, especially for vulnerable groups.

Limitations

The present review has several limitations. First, only articles in English language were considered; therefore, global representativeness cannot be claimed. Besides, grey literature or texts from official bodies which could provide insight on how regulators respond to the constant changes are also missing. Owing to the fact that the publication date of the latest review on this subject was used as a starting point for the search, the period of the investigation was relatively short; however, due to the rapidly changing nature of the review’s subject, 12 relevant and up to date publications could be identified. Given that each study has its own focus and mirrors the conditions of the country investigated, the results remain necessarily fragmentary and cannot give a comprehensive picture of the overall situation.

Appendix. Search String

(Social media OR social media channel* OR social network* OR social network* channel* OR social platform* OR online platform* OR online environment* OR online sphere* OR facebook OR twitter OR instagram OR tiktok OR twitch OR youtube OR weibo OR wechat) AND (Gambling OR online gambling OR gambling operator* OR gambling provider* OR gambling marketing OR gambling advertisement OR gambling advertising OR gambling industry OR gambling industry marketing OR digital gambling marketing).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (JS) upon reasonable request.

Notes

Examples of content and auxiliary terms and conditions for virtual slot machines and online poker, https://innen.hessen.de/sites/innen.hessen.de/files/2022-05/musternebenbestimmungen_virtuelle_automatenspiele_online_poker.pdf.

As it is unknown how many followers are registered on more than one channel, the exact number cannot be determined. The approximate figure given here refers to the minimum number.

An example for such a close interlocking can be seen in Germany, where the drawing of the lottery numbers forms part of the daily news program.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Guillou-Landreat M, Gallopel-Morvan K, Lever D, Le Goff D, Le Reste J-Y. Gambling marketing strategies and the internet: what do we know? A systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:583817. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.583817.

Torrance J, John B, Greville J, O’Hanrahan M, Davies N, Roderique-Davies G. Emergent gambling advertising; a rapid review of marketing content, delivery and structural features. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:718. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10805-w.

Thomas SL, Randle M, Bestman A, Pitt H, Bowe SJ, Cowlishaw S, Daube M. Public attitudes towards gambling product harm and harm reduction strategies: an online study of 16–88 year olds in Victoria. Australia Harm Reduct J. 2017;14:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0173-y.

Hörnle J, Schmidt-Kessen M, Littler A, Padumadasa E. Regulating online advertising for gambling – once the genie is out of the bottle … Inf Commun Technol Law. 2019;28:311–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600834.2019.1664001.

Rossi R, Nairn A. New developments in gambling marketing: the rise of social media ads and its effect on youth. Curr Addict Rep. 2022;9:385–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00457-0.

Binde P, Romild U. Self-reported negative influence of gambling advertising in a Swedish population-based sample. J Gambl Stud. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9791-x.

James RJE, Bradley A. The use of social media in research on gambling: a systematic review. Curr Addict Rep. 2021;8:235–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00364-w.

Newall PWS, Moodie C, Reith G, Stead M, Critchlow N, Morgan A, Dobbie F. Gambling marketing from 2014 to 2018: a literature review. Curr Addict Rep. 2019;6:49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00239-1.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Singer J, Kufenko V, Wöhr A, Wuketich M, Otterbach S. How do gambling providers use the social network Twitter in Germany? An explorative mixed-methods topic modeling approach. J Gambl Stud. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10158-y. One of the few studies featuring Germany. The study highlights the relevance of content marketing, while responsible gambling messages are barely used.

Russell AMT, Hing N, Bryden GM, Thorne H, Rockloff MJ, Browne M. Gambling advertising on Twitter before, during and after the initial Australian COVID-19 lockdown. J Behav Addict. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2023.00020. The study investigates the volume and content of gambling advertising during the pandemic-related lockdowns.

Lindeman M, Männistö-Inkinen V, Hellman M, Kankainen V, Kauppila E, Svensson J, Nilsson R. Gambling operators’ social media image creation in Finland and Sweden 2017–2020. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2023;40:40–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/14550725221111317. One of the few studies analysing gambling advertising on social media in Finland and Sweden.

Hernández-Ruiz A, Gutiérrez Y. Analysing the Twitter accounts of licensed Sports gambling operators in Spain: a space for responsible gambling? Commun Soc. 2021;34:65–79. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.34.4.65-79. Twitter messages of sports betting providers are usually framed positively and often designed to create surprise.

Hellman M, Männistö-Inkinen V, Nilsson R, Svensson J. Being good while being bad: How does CSR-communication on the social media serve the gambling industry? European J Commun. 2022:026732312211453. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231221145363. Social responsibility communication is used as a marketing strategy.

Biggar B, Zendle D, Wardle H. Targeting the next generation of gamblers? Gambling sponsorship of esports teams. J Public Health (Oxf). 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdac167. The study demonstrates the enormous size of the target audience for gambling advertising.

Critchlow N, Hunt K, Wardle H, Stead M. Expenditure on paid-for gambling advertising during the national COVID-19 ‘lockdowns’: an observational study of media monitoring data from the United Kingdom. J Gambl Stud. 2022:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10153-3. Spending on gambling advertising is related to overall gambling.

Balem M, Perrot B, Hardouin J-B, Thiabaud E, Saillard A, Grall-Bronnec M, Challet-Bouju G. Impact of wagering inducements on the gambling behaviors of on-line gamblers: a longitudinal study based on gambling tracking data. Addiction. 2022;117:1020–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15665. The use of wagering inducements is associated with increased gambling intensity, frequency and at-risk gambling behaviours.

Wardle H, Critchlow N, Brown A, Donnachie C, Kolesnikov A, Hunt K. The association between gambling marketing and unplanned gambling spend: synthesised findings from two online cross-sectional surveys. Addict Behav. 2022;135:107440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107440. Among the few studies that investigate (and confirm) the relationship between exposure to gambling advertising and spendings.

Noble N, Freund M, Hill D, White V, Leigh L, Lambkin D, et al. Exposure to gambling promotions and gambling behaviours in Australian secondary school students. Addict Behav Rep. 2022;16:100439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2022.100439. Exposure to online gambling ads was associated with gambling in the last month.

Gonzálvez-Vallés JE, Barquero-Cabrero JD, Caldevilla-Domínguez D, Barrientos-Báez A. Tipsters and addiction in Spain. Young people’s perception of influencers on online sports gambling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116152. One of the very few studies investigating the influence of tipsters.

Newall PWS, Weiss-Cohen L, Singmann H, Walasek L, Ludvig EA. Impact of the “when the fun stops, stop” gambling message on online gambling behaviour: a randomised, online experimental study. The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e437-e446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00279-6. Responsible gambling messages do not necessarily entail positive effects.

Bradley A, James RJE. How are major gambling brands using Twitter? Int Gambl Stud. 2019;19:451–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2019.1606927.

Johnson MR, Brock T. How are video games and gambling converging. Ontario, Canada: Gambling Research Exchange Ontario. 2019.

Gainsbury S, King D, Abarbanel B, Delfabbro P, Hing N. Convergence of gambling and gaming in digital media. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Responsible Gambling. 2015.

Clemens F, Hanewinkel R, Morgenstern M. Exposure to gambling advertisements and gambling behavior in young people. J Gambl Stud. 2017;33:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-016-9606-x.

Gainsbury SM, Delfabbro P, King DL, Hing N. An exploratory study of gambling operators’ use of social media and the latent messages conveyed. J Gambl Stud. 2016;32:125–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9525-2.

Koncz P, Demetrovics Z, Griffiths MD, Király O. The potential harm of gambling streams to minors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2023.01.020.

McGrane E, Wardle H, Clowes M, Blank L, Pryce R, Field M, et al. What is the evidence that advertising policies could have an impact on gambling-related harms? A systematic umbrella review of the literature. Public Health. 2023;215:124–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.11.019.

Smith M, Chambers T, Abbott M, Signal L. High stakes: children’s exposure to gambling and gambling marketing using wearable cameras. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2020;18:1025–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00103-3.

Kolandai-Matchett K, Wenden AM. Gaming-gambling convergence: trends, emerging risks, and legislative responses. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2022;20:2024–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00498-y.

Auer M, Griffiths MD. The use of personalized messages on wagering behavior of Swedish online gamblers: an empirical study. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;110:106402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106402.

Sirola A, Kaakinen M, Savolainen I, Paek H-J, Zych I, Oksanen A. Online identities and social influence in social media gambling exposure: a four-country study on young people. Telematics Inform. 2021;60:101582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101582.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception of the work. JS and AW created the first draft of the article. All authors revised and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Open Access

Open access funding was provided by the University of Hohenheim.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singer, J., Wöhr, A. & Otterbach, S. Gambling Operators’ Use of Advertising Strategies on Social Media and Their Effects: A Systematic Review. Curr Addict Rep 11, 437–446 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00560-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-024-00560-4