Abstract

Purpose of Review

Examine current research on how adolescents are influenced by junk food marketing; inform proposed policies to expand food marketing restrictions to protect children up to age 17.

Recent Findings

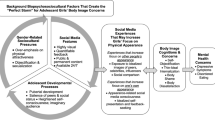

Previous food marketing effects research focused primarily on TV advertising to younger children. However, recent research with adolescents demonstrates the following: (a) unique effects of food marketing on adolescents; (b) extensive exposure to social media and other digital marketing “disguised” as entertainment and messages from peers; (c) adolescents’ still-developing and hypersensitive reward responsivity to appetitive cues; and (d) disproportionate appeals to Black and Hispanic youth, likely exacerbating health disparities affecting their communities.

Summary

Adolescents may be even more vulnerable to junk food marketing appeals than younger children. Additional research on how food marketing uniquely affects adolescents and efficacy of potential solutions to protect them from harm are critical to support stronger restrictions on junk food marketing to all children.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Cairns G, Agnes K, Hastings G, Caraher M. Systematic reviews of the evidence on the nature, extent and effects of food marketing to children. A retrospective summary. Appetite. 2013;62:209–15.

Powell LM, Harris JL, Fox T. Food marketing expenditures aimed at youth: putting the numbers in context. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):453–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.003.

World Health Organization. Set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. 2010. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44416/9789241500210_eng.pdf;jsessionid=EEDEC59E3D3C52C9340757E1C735A0C6?sequence=1. Accessed 11/9/20.

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases, 2013-2020. Geneva; 2013. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R10-en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 11/9/20.

Hawkes C, Lobstein T. Regulating the commercial promotion of food to children: a survey of actions worldwide. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:83–94.

World Health Organization. Evaluating implement of the set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. Copenhagen; 2018. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/384015/food-marketing-kids-eng.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

• Taillie LS, Busey E, Stoltze FM, Carpentier FRD. Governmental policies to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children. Nutr Rev. 2019;77(11):787–816 This narrative review describes current statutory regulations regarding food marketing to children in 16 counties and reviews the limited evidence available on their effects.

Whalen R, Harrold J, Child S, Halford J, Boyland E. Children’s exposure to food advertising: the impact of statutory restrictions. Health Promot Int. 2019;34:227–35.

John DR. Consumer socialization of children: a retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. J Consum Res. 1999;26(3):183–213.

Kelly B, King L, Chapman K, Boyland E, Bauman AE, Baur LA. A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):e86–95.

Keller KL. Brand synthesis: the multidimensionality of brand knowledge. J Consum Res. 2003;29:595–600.

Harris JL, Brownell KD, Bargh JA. The food marketing defense model: integrating psychological research to protect youth and inform public policy. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2009;3:211–71.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission. A review of food marketing to children and adolescents: follow-up report [Internet]. Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents: Activities, Expenditures, and Nutritional Profiles. 2013. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/review-food-marketing-children-and-adolescents-follow-report/121221foodmarketingreport.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

Boush DM, Friestad M, Rose GM. Adolescent skepticism toward TV advertising and knowledge of advertiser tactics. J Consum Res. 1994;21(1):165.

Buijzen M, Van Reijmersdal EA, Owen LH. Introducing the PCMC model: an investigative framework for young people’s processing of commercialized media content. Commun Theory. 2010;20(4):427–50.

Blakemore SJ, Choudhury S. Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2006;47:296–312.

Casey BJ. Beyond simple models of self-control to circuit-based accounts of adolescent behavior. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:295–319.

Folkvord F, Anschütz DJ, Boyland E, Kelly B, Buijzen M. Food advertising and eating behavior in children. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2016;9:26–31.

Pechmann C, Levine L, Loughlin S, Leslie F. Impulsive and self-conscious: adolescents’ vulnerability to advertising and promotion. J Public Policy Mark. 2005;24:202–21.

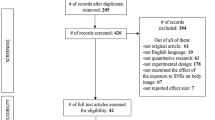

•• Qutteina Y, De Backer C, Smits T. Media food marketing and eating outcomes among pre-adolescents and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(12):1708–19 This review synthesizes the available evidence on the relationship between advertising and eating-related outcomes among pre-adolescents (8–11) and adolescents (12–19). It demonstrates significant impact but also highlights the need for more evidence, especially among older adolescents (14–19).

Thai CL, Serrano KJ, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L, Oh A. Perceptions of food advertising and association with consumption of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods among adolescents in the United States: results from a national survey. J Health Commun. 2017;22(8):638–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1339145.

Cervi MM, Agurs-Collins T, Dwyer LA, Thai CL, Moser RP, Nebeling LC. Susceptibility to food advertisements and sugar-sweetened beverage intake in non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White adolescents. J Community Health. 2017;42(4):748–56.

Critchlow N, Bauld L, Thomas C, Hooper L, Vohra J. Awareness of marketing for high fat, salt or sugar foods, and the association with higher weekly consumption among adolescents: a rejoinder to the UK government’s consultations on marketing regulation. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(14):2637–46.

Dembek C, Harris JL. Trends in television food advertising to young people: 2011 update. 2012. Available from: http://www.uconnruddcenter.org/resources/upload/docs/what/reports/RuddReport_TVFoodAdvertising_5.12.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

Harris JL, Frazier W, Kumanyika S, Ramirez A. Increasing disparities in unhealthy food advertising targeted to Hispanic and Black youth. 2019. Available from http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/TargetedMarketingReport2019.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, social media & technology. 2018. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018. Accessed 11/9/20.

Commonsense Media. Social media, social life: teens reveral their experiences. 2018. Available from: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/social-media-social-life-2018. Accessed 11/9/20.

Tatlow-Golden M, Boyland E, Jewell J, Zalnieriute M, Handsley E, Breda J. Tackling food marketing to children in a digital world: transdisciplinary perspective. Geneva; 2016. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/322226/Tackling-food-marketing-children-digital-world-trans-disciplinary-perspectives-en.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

Freeman B, Kelly B, Baur L, Chapman K, Chapman S, Gill T, et al. Digital junk: food and beverage marketing on facebook. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):56–64.

Van Dam S, Van Reijmersdal EA. Insights in adolescents’ advertising literacy, perceptions and responses regarding sponsored influencer videos and disclosures. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 2019;13(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-2-2.

OFCOM UK. Children and parents: media use and attitudes report. 2017. Available from: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/research-and-data/media-literacy-research/childrens/children-parents-2017. Accessed 11/9/20.

Montgomery KC, Chester J. Interactive food and beverage marketing: targeting adolescents in the digital age. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3S).

Freberg K, Graham K, McGaughey K, Freberg LA. Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relat Rev. 2011;37(1):90–2.

Lueck JA. Friend-zone with benefits: the parasocial advertising of Kim Kardashian. J Mark Commun. 2015;21(2):91–109.

Lawlor MA, Dunne Á, Rowley J. Young consumers’ brand communications literacy in a social networking site context. Eur J Mark. 2016;50(11):2018–40.

Qutteina Y, Hallez L, Mennes N, De Backer C, Smits T. What do adolescents see on social media? A diary study of food marketing images on social Media. Front Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02637.

• Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Roy EA, de Billy N, Czoli C. Children and adolescents’ exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14(6) This study shows the overwhelming amount of food marketing on social media targeting teens. They found that adolescents see food marketing 189 times on average per week on social media apps.

Advertising Standards Authority. ASA Monitoring Report on Online HFSS Ads. 2019. Available from: https://www.asa.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/14be798d-bd30-49d6-bcfbc9ed7e66e565.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

• Fleming-Milici F, Harris JL. Adolescents’ engagement with unhealthy food and beverage brands on social media. Appetite. 2020:146 This cross-sectional survey is the first to document extensive engagement with unhealthy brands on social media in a large sample (N = 1564) of adolescents (13–17) and higher levels of engagement among Black and less-acculturated Hispanic youth.

Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Munsell CR, Dembek C, Liu S. Fast Food FACTS: measuring progress in nutrition and marketing to children and teens. 2013. Available from: https://www.fastfoodmarketing.org/media/FastFoodFACTS_Report.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Lodolce ME, Munsell CR, Fleming-Milici F. Sugary drink FACTS 2014: some progress but much room for improvement in marketing to youth. 2014. Available from: http://www.sugarydrinkfacts.org/resources/SugaryDrinkFACTS_Report.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Shehan C, Hyary M, Haraghey KS, Li X. Snack FACTS. Evaluating snack food nutrition and marketing to youth. 2015. Available from: http://www.uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/SnackFACTS_2015_Fulldraft03.pdf. Accessed 11/9/20.

Kolb B. 3 earned media strategies for content marketing plans. 2016. Available from: https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/2016/05/earned-media-strategies/. Accessed 11/9/20.

Buchanan L, Kelly B, Yeatman H. Exposure to digital marketing enhances young adults’ interest in energy drinks: an exploratory investigation. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171226. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171226.

Murphy G, Corcoran C, Tatlow-Golden M, Boyland E, Rooney B. See, like, share, remember: Adolescents’ responses to unhealthy-, healthy- and non-food advertising in social media. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072181.

Holmberg CE, Chaplin J, Hillman T, Berg C. Adolescents’ presentation of food in social media: an explorative study. Appetite. 2016;99:121–9.

Somerville LH, Jones RM, Casey BJ. A time of change: behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain Cogn. 2010;72:124–33.

Padmanabhan A, Geier CF, Ordaz SJ, Teslovich T, Luna B. Developmental changes in brain function underlying the influence of reward processing on inhibitory control. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1(4):517–29.

Van Leijenhorst L, Zanolie K, Van Meel CS, Westenberg PM, Rombouts SARB, Crone EA. What motivates the adolescent? Brain regions mediating reward sensitivity across adolescence. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(1):61–9.

Vara AS, Pang EW, Vidal J, Anagnostou E, Taylor MJ. Neural mechanisms of inhibitory control continue to mature in adolescence. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2014;10:129–39.

Davidow JY, Foerde K, Galván A, Shohamy D. An upside to reward sensitivity: the hippocampus supports enhanced reinforcement learning in adolescence. Neuron. 2016;92(1):93–9.

Bruce AS, Bruce JM, Black WR, Lepping RJ, Henry JM, Cherry JBC, et al. Branding and a child’s brain: an fMRI study of neural responses to logos. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(1):118–22.

•• Gearhardt AN, Yokum S, Harris JL, Epstein LH, Lumeng JC. Neural response to fast food commercials in adolescents predicts intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(3):493–502 This study found that fast-food commercials can be implicated in greater food intake for adolescents by activating brain reward regions. Further, the results show that adding healthier fast-food commercials to the food advertising landscape might not be beneficial in encouraging healthier eating.

Rapuano KM, Huckins JF, Sargent JD, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM. Individual differences in reward and somatosensory-motor brain regions correlate with adiposity in adolescents. Cereb Cortex. 2016;114(1):160–5.

Burger KS, Stice E. Neural responsivity during soft drink intake, anticipation, and advertisement exposure in habitually consuming youth. Obesity. 2014;22(2):441–50.

Yokum S, Gearhardt AN, Harris JL, Brownell KD, Stice E. Individual differences in striatum activity to food commercials predict weight gain in adolescents. Obesity. 2014;22(12):2544–51.

Folkvord F, Anschütz DJ, Buijzen M, Valkenburg PM. The effect of playing advergames that promote energy-dense snacks or fruit on actual food intake among children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):239–45.

Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in US children and adolescents, 2013-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2410–8.

Dunford EK, Popkin BM, Ng SW. Recent trends in junk food intake in U.S. children and adolescents, 2003–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.023.

Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Koma JW, Li Z. Trends in beverage consumption among children and adults, 2003-2014. Obesity. 2018;26(2):432–41.

Grier SA, Kumanyika S. Targeted marketing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:349–69.

Fleming-Milici F, Harris JL. Television food advertising viewed by preschoolers, children and adolescents: contributors to differences in exposure for black and white youth in the United States. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13(2):103–10.

Herrera AL, Pasch KE. Targeting Hispanic adolescents with outdoor food & beverage advertising around schools. Ethn Health. 2018;23(6):691–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2017.1290217.

Adeigbe RT, Baldwin S, Gallion K, Grier S, Ramirez AG. Food and beverage marketing to Latinos: a systematic literature review. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(5):569–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114557122.

Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Sanon OC, Schechter CB. Unhealthful food-and-beverage advertising in subway stations: targeted marketing, vulnerable groups, dietary intake, and poor health. J Urban Health. 2017;94(2):220–32.

Lowery BC, Sloane DC. The prevalence of harmful content on outdoor advertising in Los Angeles: land use, community characteristics, and the spatial inequality of a public health nuisance. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):658–64.

• Bragg MA, Miller AN, Kalkstein DA, Elbel B, Roberto CA. Evaluating the influence of racially targeted food and beverage advertisements on Black and White adolescents’ perceptions and preferences. Appetite. 2019;140:41–9. https://medium.com/cokeleak/new-email-leak-coca-cola-policy-priorities-390eb1dfda82. Accessed 11/9/20. This experimental study demonstrates that Black-targeted food ads have greater impact on Black youth compared to White youth, but that targeted ads influenced both group more than non-targeted ads. These findings provide insights into why targeted food advertising has increased.

Hyary M, Harris JL. Hispanic youth visits to food and beverage company websites. Heal Equity. 2017;1(1):134–8.

• Harris J, Frazier W, Fleming-Milici F, Hubert P, Rodriguez-Arauz G, Grier S, et al. A qualitative assessment of US Black and Latino adolescents’ attitudes about targeted marketing of unhealthy food and beverages. J Child Media. 2019;13(3):295–316 Focus groups with low-income Black and Hispanic adolescents revealted strong affinity for targeted brands, but ambivalent attitudes about unhealthy food marketing targeting their communities. These results suggest an opportunity for countermarketing and grassroots campaigns.

Pfister K. New #CokeLeak: Coca-Cola’s Policy Priorities. Medium.com. 2016; Available from: https://medium.com/cokeleak/new-email-leak-coca-cola-policy-priorities-390eb1dfda82. Accessed 11/9/20.

Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):259–94.

Nixon L, Mejia P, Cheyne A, Dorfman L. Big Soda’s long shadow: news coverage of local proposals to tax sugar-sweetened beverages in Richmond, El Monte and Telluride. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(3):333–47.

Truman E, Elliott C. Identifying food marketing to teenagers: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):1–10.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission. FTC staff reminds influencers and brands to clearly disclose relationships: Press release; 2017. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/04/ftc-staff-reminds-influencers-brands-clearly-disclose. Accessed 11/9/20.

Chaloupka FJ, Powell LM, Warner KE. The use of excise taxes to reduce tobacco, alcohol and sugary beverage consumption. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):187–201.

•• Small DM, Di Feliceantonio AG. Neuroscience: Processed foods and food reward. Science. 2019;363(6425):346–7 This paper provides a model on how processed foods hijack our body’s inborn signals governing food consumption.

Schulte EM, Avena NM, Gearhardt AN. Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117959.

Funding

JLH and FFM received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Disclaimer

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Food Addiction

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, J.L., Yokum, S. & Fleming-Milici, F. Hooked on Junk: Emerging Evidence on How Food Marketing Affects Adolescents’ Diets and Long-Term Health. Curr Addict Rep 8, 19–27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00346-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00346-4