Abstract

Purpose of Review

The aim of this article was to review current research regarding social cognition (SC) in gambling disorder (GD), to (i) compile and synthetize the current state of existing literature on this topic, and (ii) propose cognitive remediation therapy approaches focused on SC for clinicians.

Recent Findings

It is well known that disordered gamblers show impairment regarding non-social cognitive functions such as inhibition, attention, and decision-making. Furthermore, patients with substance use disorders also present certain deficits regarding social information processing which are difficult to differentiate from the intrinsic toxic effects linked to drugs or alcohol consumption.

Summary

To date, relatively little research has been undertaken to explore SC in gambling disorder (GD) with neuropsychological tasks. Preliminary results suggest impaired non-verbal emotion processing, but only one study has directly measured SC in GD. As a consequence, future research on this framework should propose diverse measures of SC, while controlling for other factors such as personality traits and subtypes of disordered gamblers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gambling disorder (GD), formerly known as “Pathological gambling” (PG) [1], has been newly classified in the DSM-5 in the “Substances-related and addictive behavior” section. This diagnostic classification defines GD as a loss of control over behavior and repetition of the problematic behavior despite its negative consequences on social, professional, or family spheres. The repetition may be to obtain pleasure, or to relieve an internal discomfort [2].

Comprehension of addiction phenomena traditionally relies on numerous risk factor models. Olievenstein’s model, for example, postulates that there are three types of risk factors that could trigger or maintain addiction: (1) the context (socio-demographical factors for example), (2) the addiction’s object (and its availability) and (3) the individual [3]. Neurocognitive functioning is part of this third factor, and can be further subdivided into three components: (i) the impulsive system, which is an automatic system handling routine situations; (ii) the reflective system, which allows an individual to act and react appropriately to new situations and make complex decisions [4]; and (iii) the interoceptive system, which translates physical sensations into subjective information to provide information about risks or rewards in complex situations [5].

Regarding the reflective system more specifically, two ways of processing can be distinguished. On the one hand, the “cool executive functioning” is underlied by dorsolateral frontal networks and handles executive functions dealing with emotionally neutral information. On the other hand, the “hot” executive component is underpinned by the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and paralimbic orbitomedial structures. This network is in charge of provoking bodily sensations based on experience from situations resembling the actual context, and on memory and knowledge, to give a global sensation that can then guide the decision-making process considering cognitive and emotional information [5, 6].

Addictive behavior is thus described as an imbalance of these systems, namely impulsive system hyperactivity and reflective system hypo-activity, while the interoceptive system would be impaired as well by redirecting resources from the reflective system to the impulsive system, leading to a control deficit and thus increasing allocation of resources to gambling [5].

Using this framework, therefore, behavioral addiction research has mainly focused on cool cognitive functions, highlighting alterations in attention processing, inhibition, flexibility, and decision-making [7,8,9,10] and linking it with neurological bases [11]. In contrast, little is known about hot functions in GD [9]. It has been shown that individuals with GD show specific patterns of response [12] and neuronal connectivity [13] in an affective decision-making task, suggesting an alteration of the functioning of the hot network, and more specifically, the VMPFC. This brain area is also involved in affective theory of mind (ToM) functioning [14] which is the ability to infer emotions to one and others [15] and is included in the broader concept of social cognition (SC) [16]. SC is a broad term that regroups various functions that allow an individual to perceive and understand social information and construct efficient social relationships [17, 18]. According to the model of Strack & Deutsch, this ensemble of functions can be classified as a dual processing using both reflective and impulsive systems [19,20,21]. Table 1 defines several SC functions, presents measures that may be used to assess them in a clinical context, while highlighting those corresponding to neuropsychological tasks. The primary objectives of neuropsychological tasks are to “(i) detect neurological dysfunction and guide differential diagnosis, (ii) characterize changes in cognitive strengths and weaknesses over time, and (iii) guide recommendations regarding everyday life ant treatment planning” [43]. Thus, those tasks are objective measures of cognitive performances and can be opposed to PRO (patient-reported outcomes) that are “direct subjective assessment by the patient of elements of their health” [44]. Such measures mainly assess emotion recognition and ToM abilities [45]. Moreover, SC has mainly been investigated in psychiatric conditions such as autism spectrum disorder [46] or schizophrenia [18]. It has been acknowledged as a mediator between social functioning and cool neurocognition [16]. Furthermore, SC abilities have also been shown to be more correlated to social functioning than to cool cognitive functioning, in a population of patients with schizophrenia [16, 47], and in a population of patients with traumatic brain injury [48]. Regarding addictions in general, patients with alcohol use disorder are impaired in processing facial emotions [49], and patients with substance use disorder show lower levels of emotional empathy than control subjects [50,51,52]. Nevertheless, it is difficult to differentiate alterations linked to the intrinsic toxic effect of drugs or alcohol from dysfunction linked to an addiction mechanism, even if functional imaging research has suggested that cerebral markers exist before the onset of addictive behavior [53]. Studying neurocognitive alterations of patients suffering from behavioral addictions may allow the identification of SC deficits due to the addictive vulnerability rather than those caused by the intake of exogenous neurotoxic substances. Moreover, direct measures such as neuropsychological tasks may avoid biases in the measurement of SC, as is the case with self-reported scales, which rather assess the perception of one’s social abilities, i.e., social metacognition.

Previous research has shown that individuals with subclinical forms of pathological gambling (i.e., those who gambled and met 2–3 criteria of the DSM-IV) scored lower than controls on a psychosocial functioning scale [54]. Nevertheless, the relationship between GD, social functioning and SC is still unclear. SC is a factor that could trigger, maintain or cause relapse of the GD. The aim of this article was to review recent research on SC and GD, based on a systematic review investigating the link between SC abilities and disordered gambling using a direct neuropsychological measure of SC. The objectives were to (i) characterize SC deficits linked to non-substance addiction, and synthetize the current state of existing literature on this topic and (ii) further understand the profile of individuals with GD, which could also hopefully provide guidance regarding cognitive remediation therapies focused on SC for health care professionals.

Method

Search Strategy

The research strategy follows instructions of the Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [55].

Research was performed using three databases (PsycINFO, PubMed and ScienceDirect). A combination of key words and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms relating to GD (n = 5) on the one hand, and to SC components (n = 17) on the other hand was used (see Table 2 for an exhaustive list). Only publications in English or French between January 2013 and September 2018 were screened. Indeed, the article by Challet-Bouju et al. in 2017 [9] investigated cognitive alterations, including SC, in pathological gambling and did not find any previous study for SC. Furthermore, social cognition is a recent field of interest in addiction, which justify the focus on the last 5 years. This search was completed using a manual search by exploring the bibliographic reference lists from articles included to screen for potential eligible missing articles.

All articles dealing with SC explored with direct neuropsychological measures and with a link with GD were included. There was no exclusion criterion in regard to participants assessed to screen the largest number of articles possible, especially given the recent interest in SC for GD and the relatively few articles published [9].

Study Selection and Data Extraction

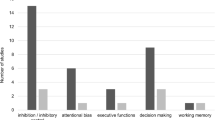

All records were screened by the first author (EH). A preliminary assessment of the article titles from the initial electronic search was used to exclude all articles that were clearly off topic and resulted in a large number of exclusions. The remaining abstracts were screened for eligibility, and 18 articles were read fully. Articles regarding cognitive assessment were read in order to not miss any social cognition evaluation, while a particular attention was given to methods of articles dealing with social support and quality of life of gamblers in order to check for the presence of neuropsychological tasks among questionnaires (see Table 3). The flowchart of the review process is presented in Fig. 1.

Results

As depicted in Fig. 1, 18 articles met our selection criterion, but only one article was finally retained [56] (see Table 3 for reasons of exclusion) and was focused on non-verbal emotion processing.

Population Assessed

The only article selected was focused on non-verbal emotion processing and included outpatients seeking treatment for pathological gambling at the Brugman University Hospital [56]. Diagnosis of pathological gambling was made based on DSM-IV criteria (score from 0 to 10, 5 criteria have to be present to be diagnosed), and patients were excluded if they had a history of psychiatric disorders. The Pathological Gambling group (PG) was composed of 22 male participants. The mean score on the DSM-IV scale also assessed the severity of PG (mean = 7.73, ± 1.52). A control group of 22 males consisted of healthy participants matched on age and education level (C).

Non-verbal Emotion Assessment

The study by Kornreich et al. [56] highlighted the deficits in emotion recognition in individuals with PG, using the same methodology as those for substance-related addictions [57]. Indeed, emotion processing was assessed using an experimental task on three modalities: musical, vocal, and facial. Regarding music modality, 56 piano excerpts were presented to participants (14 of each emotion for happiness, sadness, threat, and peacefulness). They had to judge the intensity of each emotion on a scale from 0 to 9. Concerning facial modality, stimuli consisted of 25 faces presented during 0.5 s and expressing 4 emotions (happiness, sadness, fear, and anger) and a neutral condition. Participants also had to rate the intensity of the four emotions for each picture on a scale from 0 to 9. Finally, regarding vocal modality, 35 affective non-verbal burst excerpts were used [58], 5 for each emotion (anger, happiness, surprise, disgust, sadness) and a neutral condition. Once again, participants had to rate the intensity of each of the 5 emotions on a scale from 0 to 9.

Outcomes consisted of the identification of the correct emotion, i.e., accuracy: if the emotion that was rated with the highest score was the one really depicted, then the response was scored correct. Regarding neutral stimuli, a response was correct if all emotions were scored as absent or of the same intensity. Intensity scores of each response were also recorded.

Results Obtained

Regarding musical modality, accuracy was not significantly different between groups, overall and per emotion. The intensity rating only differed for the assessment of peacefulness, which was underestimated by the PG group. Regarding the vocal modality, the PG group was significantly less accurate in identifying the targeted emotion compared with controls, including the detection of neutral emotions. The intensity rating was only different for neutral conditions, with an overestimation of intensity in this modality. Finally, concerning facial modality, PG was significantly less accurate in identifying the targeted emotion, without any specific significant difference between emotions. The intensity rating was only different for the neutral condition in which PG significantly overestimated the intensity compared with controls.

Discussion and Limitations

This research highlighted the alteration of non-verbal emotion processing in pathological gamblers, which suggests impaired capacities for processing social cues. Pathological gamblers specifically presented difficulties in processing neutral cues. This profile has also been found in alcohol-dependent populations, suggesting either common deficits in processing social cues or attentional deficits known to be present in both populations [57, 59]. Such difficulties in processing social cues could lead to social difficulties in daily life, although these were not assessed in the Kornreich study. Moreover, this research did not link the performance in emotion processing with personality traits that have been linked to SC, such as alexithymia. Indeed, this personality dimension has been found to be higher for a large percent of gamblers [60] and could impact SC performance [59, 61]. Furthermore, because no women were assessed in this study, these results cannot be generalized for the GD population as a whole.

Discussion

SC and GD Research

Only one study was identified as assessing SC in GD, using direct neuropsychological measures. This study [56] made direct observations of the social capacities of pathological gamblers concerning emotions processing. This research brings emotion recognition deficits to light regarding three different natures of emotional stimuli (faces, voices and music). Nevertheless, no link was made with personality traits, specifically alexithymia, which is known to impact facial emotion recognition [61, 62], neither with social functioning in daily life. Moreover, the sample only included males, making it difficult to generalize these results.

This study highlighted specific deficits in an addiction group of patients despite the absence of substance abuse. These findings support the idea that social cognitive impairment could be linked to addiction per se and may exist before the onset of gambling [3, 5], and not only be linked to the intrinsic neurotoxic effects of substances, even though many studies are required to confirm and extend these results.

Other Components of SC

Given that social functioning involves a large panel of abilities, it is also interesting to explore what have been done regarding the other components of SC, which have been assessed with self-reported measures (i.e., were not included in the systematic review).

Emotional Intelligence

Using the Emotional Quotient Inventory [63], two studies have shown a link between scores on the interpersonal scale and SOGS (South Oaks Gambling Screen [64]) scores in a population of non-problematic poker players [65] and a population of special needs students [66]. Those articles suggested that poor quality of interpersonal relationships may be found in populations of non-problematic gamblers, without the possibility of concluding the direction of the link of causality.

Empathy

The IRI questionnaire [67] has been used in a population of outpatients seeking treatment for GD. The results show that compared with a control group, the GD group showed lower global scores and scores significantly lower on the perspective taking (PT) and fantasy (F) scales and higher on the personal distress (PD) scale [68]. This research seems to imply that the ability to infer and understand emotions in oneself and others may be altered in the GD population.

Theory of Mind

To our knowledge, no research has explored ToM competencies in GD. Nevertheless, it has been shown that people with alcohol use disorder present altered ToM abilities [69] and, more precisely, specific difficulties regarding affective ToM, while cognitive ToM abilities would be preserved [70]. Nevertheless, it is still unknown whether these deficits are linked to the consumption of neurotoxic substances or to addictive behavior.

Factors That Could Impact SC Assessment

Alexithymia

Alexithymia is a personality trait describing the tendency to have difficulties in processing emotions [71, 72]. It is not a social cognitive function per se, but its level seems to impact the social functioning of the individuals, as well as their ability to identify emotional facial expressions [62]. Therefore, it must be taken into account when social perception is assessed.

Gender and Social Cognitive Measurement

The study reviewed did not assess women, making the generalization of results difficult. Nevertheless, the incidence of women as pathological gamblers is lower than men, which could explain imbalanced groups and difficulties in comparing gender-stratified samples [73], especially with low sample sizes. Regarding other social cognitive components, empathy appears to be higher in females than males [74], and women tend to have higher scores on the EQ-I than men [75]. Parker et al. [66] measured gender effects and confirmed this gender difference on the EQ-I YV in a clinical population of adolescents. Thus, gender needs to be assessed and taken into account when measuring SC performance.

Summary of SC Assessment in GD and Perspectives for Future Research

Taken together, these studies may imply a global alteration of social cognitive abilities in the GD population, going from a perceptual level (difficulties in identifying emotional cues and one’s own emotions) to the altered quality of interpersonal relationships.

Nevertheless, future studies using neuropsychological tasks may also need to take into account some specificity linked to the study of SC, such as the impact of personality traits or gender. It is also important to assess global intellectual functioning to control the impact of attention or executive deficits on SC performance [76]. It will also be essential to take into account the impact of GD severity, duration of gambling and other comorbidities, as these are known to influence SC performance in patients with substance use disorders [52].

To conclude, this research suggested the presence of SC deficits in an addictive disorder without the use of psychoactive substances, which may imply that such SC deficits are independent of intrinsic toxic effects of substance. However, it is still unclear whether these deficits pre-exist or appear after the onset of gambling. Only longitudinal studies would clarify this question and confirm whether cognitive performance does or does not decline with gambling practice. Eventually, further original research is needed to better understand SC in GD and to improve the understanding of the concept of addiction and to encourage the inclusion of social cognitive therapies in existing programs.

Clinical Implications: Cognitive Remediation Therapy and SC

Cognitive remediation is a therapy program aimed at improving cognitive functioning by training existing abilities or work on the application of novel cognitive strategies to generalize improvements to daily life [77]. This type of program is mainly proposed to improve cool functioning in diverse pathologies such as schizophrenia [78], anorexia nervosa [79], or traumatic brain injury [80]. Nevertheless, social cognitive training has also been developed to address SC deficits to enhance several aspects of SC by practicing and applying exercises to daily life [81]. Several programs have been proposed, such as the RC2S (Cognitive Remediation of Social Cognition in Schizophrenia) [82] for patients with schizophrenia, the SCIT (Social Cognition and Interaction Training) [83] for schizophrenic [84] or bipolar patients [85], or the CREST (Cognitive Remediation and Emotion Skills Training) for anorexic patients [86]. Overall, it seems that social cognitive therapy improves social functioning [81, 87], neuropsychological tasks’ performances assessing SC (emotion processing, ToM abilities) [81, 85, 87], as well as self-reported measures of alexithymia and anhedonia [86]. Regarding substance use disorder, existing programs target mainly cool functioning [88, 89], as is the case for gaming disorder or GD, for which existing computerized cognitive remediation programs focus on cognitive bias toward the object of addiction [90, 91]. However, to our knowledge, no attempt at social cognitive therapy has been made to improve SC in GD patients. Nevertheless, it seems now important to add cognitive therapy that links cold and hot functioning as a complement to existing therapies [92,72,94]. Thus, the creation of this type of cognitive therapy focused on both neurocognition and SC could improve global cognitive functioning and social functioning, which may participate in the maintenance of abstinence.

Conclusion

Only one published study has investigated SC with neuropsychological measures in pathological gamblers. Preliminary results are promising and tend to highlight a social cognitive impairment. However, more studies are needed to confirm and extend these results and to control certain factors, such as personality traits and gender. This is an important new avenue of research that may allow better characterization of the social cognitive profiles of gamblers and bolster the current literature. Furthermore, if studies confirm specific deficits of SC in GD, this may give alternative leads for social cognitive remediation therapies to integrate this solution with already known programs.

Change history

05 December 2019

The original article unfortunately contained a mistake. Some references mentioned in Table 1 have been misplaced and not included in the final bibliography.

References

American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: Amer Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Goodman A. Addiction: definition and implications. Addiction. 1990;85:1403–8.

Olievenstein C. Destin du toxicomane. Paris: Fayard; 1984.

Burgess PW, Simons JS. Theories of frontal lobe executive function: clinical applications. In: Halligan PW, Wade DT, editors. The effectiveness of rehabilitation for cognitive deficits: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 211–31.

Noël X, Brevers D, Bechara A. A neurocognitive approach to understanding the neurobiology of addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:632–8.

Zelazo PD, Carlson SM. Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: development and plasticity. Child Dev Perspect. 2012;6:354–60.

Ciccarelli M, Griffiths MD, Nigro G, Cosenza M. Decision making, cognitive distortions and emotional distress: a comparison between pathological gamblers and healthy controls. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2017;54:204–10.

Fauth-Bühler M, Mann K, Potenza MN. Pathological gambling: a review of the neurobiological evidence relevant for its classification as an addictive disorder: pathological gambling. Addict Biol. 2017;22:885–97.

Challet-Bouju G, Bruneau M, Victorri-Vigneau C, Grall-Bronnec M. Cognitive remediation interventions for gambling disorder: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2017;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01961.

Vizcaino EJV, Fernandez-Navarro P, Blanco C, Ponce G, Navio M, Moratti S, et al. Maintenance of attention and pathological gambling. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:861–7.

Potenza MN. The neural bases of cognitive processes in gambling disorder. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18:429–38.

Cavedini P, Riboldi G, Keller R, D’Annucci A, Bellodi L. Frontal lobe dysfunction in pathological gambling patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:334–41.

Genauck A, Quester S, Wüstenberg T, Mörsen C, Heinz A, Romanczuk-Seiferth N. Reduced loss aversion in pathological gambling and alcohol dependence is associated with differential alterations in amygdala and prefrontal functioning. Scientific Reports Nature. 2017;7:11.

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Berger BD, Goldsher D, Aharon-Peretz J. Impaired “affective theory of mind” is associated with right ventromedial prefrontal damage. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2005;18:55–67.

Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav Brain Sci. 1978;1:515–26.

Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:20.

Adolphs R. The neurobiology of social cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:231–9.

Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:620–31.

Evans JSBT. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:255–78.

Strack F, Deutsch R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8:220–47.

Deutsch, Roland, Strack F (2006) Reflective and impulsive determinants of addictive behavior. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW (eds) Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. SAGE, pp 45–57.

Phillips ML. Understanding the neurobiology of emotion perception: implications for psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:190–2.

Ekman P, Friesen WV. Pictures of facial affect. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1976.

Bertoux M, Delavest M, de Souza LC, Funkiewiez A, Lépine J-P, Fossati P, et al. Social Cognition and Emotional Assessment differentiates frontotemporal dementia from depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:411–6.

Bowers D, Blonder LX, Heilman KM. Florida Affect Battery. Center for Neuropsychological Studies, Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory. University of Florida; 1999.

McDonald S, Flanagan S, Rollins J, Kinch J. TASIT: A new clinical tool for assessing social perception after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003;18:219–38.

Tomei A, Besson J, Grivel J. Linking empathy to visuospatial perspective-taking in gambling addiction. Psychiatry Research. 2017;250:177–84.

Davis M. A Multidimensional Approach to Individual Differences in Empathy. JSAS Catalog Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10.

Ferrari V, Smeraldi E, Bottero G, Politi E. Addiction and empathy: a preliminary analysis. Neurological Sciences. 2014;35:855–9.

Maurage P, Grynberg D, Noël X, Joassin F, Philippot P, Hanak C, et al. Dissociation Between Affective and Cognitive Empathy in Alcoholism: A Specific Deficit for the Emotional Dimension. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1662–8.

Decety J, Moriguchi Y. The empathic brain and its dysfunction in psychiatric populations: implications for intervention across different clinical conditions. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2007;1:22.

Bydlowski S, Corcos M, Paterniti S, Guilbaud O, Jeammet P, Consoli SM. [French validation study of the levels of emotional awareness scale]. Encephale. 2002;28:310–20.

Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1978;1:515–26.

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Shur S, Barcai-Goodman L, Medlovich S, Harari H, Levkovitz Y. Dissociation of cognitive from affective components of theory of mind in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2007;149:11–23.

Baron-Cohen S, O’riordan M, Stone V, Jones R, Plaisted K. Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 1999;29:407–418.

Baron-Cohen S, Bowen DC, Holt RJ, Allison C, Auyeung B, Lombardo MV, et al. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test: Complete Absence of Typical Sex Difference in ~400 Men and Women with Autism. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0136521.

Desgranges B, Laisney M, Bon L, Duval C, Mondou A, Bejanin A, et al. TOM-15: a false-belief task to assess cognitive theory of mind. Revue de neuropsychologie. 2012;4:216–20.

Happé FG. An advanced test of theory of mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. Journal of autism and Developmental disorders. 1994;24:129–154.

Bosco FM, Colle L, De Fazio S, Bono A, Saverio R, Tirassa M. Th.o.m.a.s.: An exploratory assessment of Theory of Mind in schizophrenic subjects. Consciousness and Cognition. 2009;18:306–19.

Bar-On R. Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory: Short Technical Manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2002.

Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotionnal Intelligence. Baywood Publishing Co. 1990;27.

Bar-On R. The Bar-On Model of Emotional-Social Intelligence (ESI). Psichothema. 2006;18:13–25.

Casaletto KB, Heaton RK. Neuropsychological assessment: past and future. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2017;23:778–90.

Rothman ML, Beltran P, Cappelleri JC, Lipscomb J, Teschendorf B. Patient-reported outcomes: conceptual issues. Value Health. 2007;10:S66–75.

Henry J, Cowan D, Lee T, Sachdev P. Recent trends in testing social cognition. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:133–40.

Pelphrey K, Adolphs R, Morris JP. Neuroanatomical substrates of social cognition dysfunction in autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:259–71.

Fett A-KJ, Viechtbauer W, Dominguez M-G, Penn DL, van Os J, Krabbendam L. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:573–88.

Ubukata S, Tanemura R, Yoshizumi M, Sugihara G, Murai T, Ueda K. Social cognition and its relationship to functional outcomes in patients with sustained acquired brain injury. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:2061–8.

Donadon M, de Lima OF. Recognition of facial expressions by alcoholic patients: a systematic literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;1655.

Ferrari V, Smeraldi E, Bottero G, Politi E. Addiction and empathy: a preliminary analysis. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:855–9.

Maurage P, Grynberg D, Noël X, Joassin F, Philippot P, Hanak C, et al. Dissociation between affective and cognitive empathy in alcoholism: a specific deficit for the emotional dimension. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1662–8.

Bora E, Zorlu N. Social cognition in alcohol use disorder: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2016;112:40–8.

Glahn DC, Lovallo WR, Fox PT. Reduced amygdala activation in young adults at high risk of alcoholism: studies from the Oklahoma family health patterns project. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1306–9.

Weinstock J, April LM, Kallmi S. Is subclinical gambling really subclinical? Addict Behav. 2017;73:185–91.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535–5.

Kornreich C, Saeremans M, Delwarte J, Noël X, Campanella S, Verbanck P, et al. Impaired non-verbal emotion processing in pathological gamblers. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:125–9.

Kornreich C, Brevers D, Canivet D, Ermer E, Naranjo C, Constant E, Verbanck P, Campanella S, Noël X (2012) Impaired processing of emotion in music, faces and voices supports a generalized emotional decoding deficit in alcoholism 9.

Belin P, Fillion-Bilodeau S, Gosselin F. The Montreal affective voices: a validated set of nonverbal affect bursts for research on auditory affective processing. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:531–9.

Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, de Beurs E, Van den Brink W. Pathological gambling: a comprehensive review of biobehavioral findings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:123–41.

Bonnaire C, Bungener C, Varescon I. Subtypes of French pathological gamblers: comparison of sensation seeking, alexithymia and depression scores. J Gambl Stud. 2009;25:455–71.

Samur D, Tops M, Schlinkert C, Quirin M, Cuijpers P, Koole SL. Four decades of research on alexithymia: moving toward clinical applications. Front Psychol. 2013;4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00861.

Grynberg D, Chang B, Corneille O, Maurage P, Vermeulen N, Berthoz S, et al. Alexithymia and the processing of emotional facial expressions (EFEs): systematic review, unanswered questions and further perspectives. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42429.

Bar-On R. Bar-On emotional quotient inventory: short technical manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2002.

Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The south oaks gambling screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1184–8.

Schiavella M, Pelagatti M, Westin J, Lepore G, Cherubini P. Profiling online poker players: are executive functions correlated with poker ability and problem gambling? J Gambl Stud. 2018;34:823–51.

Parker JDA, Summerfeldt LJ, Taylor RN, Kloosterman PH, Keefer KV. Problem gambling, gaming and internet use in adolescents: relationships with emotional intelligence in clinical and special needs samples. Personal Individ Differ. 2013;55:288–93.

Davis MH (1980) A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy.

Tomei A, Besson J, Grivel J. Linking empathy to visuospatial perspective-taking in gambling addiction. Psychiatry Res. 2017;250:177–84.

Le Berre A-P, Fama R, Sullivan EV. Executive functions, memory, and social cognitive deficits and recovery in chronic alcoholism: a critical review to inform future research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:12.

Maurage P, D’Hondt F, de Timary P, Mary C, Franck N, Peyroux E. Dissociating affective and cognitive theory of mind in recently detoxified alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:1926–34.

Bibby PA, Ross KE. Alexithymia predicts loss chasing for people at risk for problem gambling. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:630–8.

Sifneos PE, Apfel-Savitz R, Frankel FH (1977) The phenomenon of ‘Alexithymia.’ Psychother Psychosom 28:47–57

Abbott M, Romild U, Volberg R. The prevalence, incidence, and gender and age-specific incidence of problem gambling: results of the Swedish longitudinal gambling study (Swelogs). Addiction. 2018;113:699–707.

Gilet A-L, Mella N, Studer J, Grühn D, Labouvie-Vief G. Assessing dispositional empathy in adults: a French validation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Can J Behav Sci / Revue Can Sci Comport. 2013;45:42–8.

Mandell B, Pherwani S. Relationship between emotional intelligence and transformational leadership style: a gender comparison. J Bus Psychol. 2003;17:18.

Merceron K, Prouteau A. Évaluation de la cognition sociale en langue française chez l’adulte: outils disponibles et recommandations de bonne pratique clinique. L’Évolution Psychiatrique. 2013;78:53–70.

Darmedru C. Cognitive remediation and social cognitive training for violence in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:266–74.

Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk S, Czobor P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatr. 2011;168:472–85.

Dahlgren L, Rø O. A systematic review of cognitive remediation therapy for anorexia nervosa: development, current state and implications for future research and clinical practice. J Eat Disord. 2014;2:12.

Bogdanova Y, Yee MK, Ho VT, Cicerone KD. Computerized cognitive rehabilitation of attention and executive function in acquired brain injury: a systematic review. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31:419–33.

Kurtz MM, Gagen E, Rocha NBF, Machado S, Penn DL (2016) Comprehensive treatments for social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a critical review and effect-size analysis of controlled studies. Clinical Psychology Review 80–89.

Peyroux E, Franck N. RC2S: a cognitive remediation program to improve social cognition in schizophrenia and related disorders. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:11.

Penn D, Roberts D, Munt E, Silverstein E, Jones N, Sheitman B. A pilot study of social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:357–9.

Wang Y, Roberts D, Xu B, Cao R, Yan M, Jiang Q. Social cognition and interaction training for patients with stable schizophrenia in Chinese community settings. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:751–5.

Lahera G, Benito A, Montes JM, Fernandez-Liria A, Olbert CM, Penn DL. Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for outpatients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;146:132–6.

Tchanturia K, Doris E, Mountford V, Fleming C. Cognitive Remediation and Emotion Skills Training (CREST) for anorexia nervosa in individual format: self-reported outcomes. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;53:7.

Kurtz MM, Richardson CL. Social cognitive training for schizophrenia: a meta-analytic investigation of controlled research. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:1092–104.

Rezapour T, DeVito E, Sofuoglu M, Ekhtiari H. Perspectives on neurocognitive rehabilitation as an adjunct treatment for addictive disorders: from cognitive improvement to relapse prevention. Prog Brain Res. 2016;224:25.

Sofuoglu M, DeVito E, Waters AJ, Carroll KM. Cognitive enhancement as a treatment for drug addictions. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:452–63.

Rabinovitz S, Nagar M. Possible end to an endless quest? Cognitive bias modification for excessive multiplayer online gamers. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18:581–7.

Boffo M, Willemen R, Pronk T, Wiers RW, Dom G. Effectiveness of two web-based cognitive bias modification interventions targeting approach and attentional bias in gambling problems: study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:13.

Peña J, Ibarretxe-Bilbao N, Sánchez P, Iriarte MB, Elizagarate E, Garay MA, et al. Combining social cognitive treatment, cognitive remediation, and functional skills training in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2:7.

Horan WP, Green MF. Treatment of social cognition in schizophrenia: current status and future directions. Schizophr Res. 2019;203:3–11.

Berry J, Jacomb I, Lunn J, et al. A stepped wedge cluster randomised trial of a cognitive remediation intervention in alcohol and other drug (AOD) residential treatment services. BMC psychiatry. 2019;19:11.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Elodie Hurel, Nicolas Bukowski, and Emeline Eyzop declare that they have no conflict of interest. Marie Grall-Bronnec and Gaëlle Challet-Bouju declare that the endowment funds of the Nantes University Hospital have received funding from gambling industry (FDJ and PMU) in the form of a philanthropic sponsorship (donations that do not assign purpose of use). FDJ and PMU did not exert any editorial influence over this article.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: Some references have been misplaced and not included in the final bibliography. Indeed, the table 1 cites references that do not correspond to the articles supposed to be cited.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Gambling

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hurel, E., Challet-Bouju, G., Bukowski, N. et al. Gambling and Social Cognition: a Systematic Review. Curr Addict Rep 6, 547–555 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00280-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00280-0