Abstract

Scientific interest in behavioral addictions (such as Internet gaming disorder [IGD]) has risen considerably over the last two decades. Moreover, the inclusion of IGD in Section 3 of DSM-5 will most likely stimulate such research even more. Although the inclusion of IGD appears to have been well received by most of the researchers and clinicians in the field, there are several controversies and concerns surrounding its inclusion. The present paper aims to discuss the most important of these issues: (i) the possible effects of accepting IGD as an addiction; (ii) the most important critiques regarding certain IGD criteria (i.e., preoccupation, tolerance, withdrawal, deception, and escape); and (iii) the controversies surrounding the name and content of IGD. In addition to these controversies, the paper also provides a brief overview of the recent findings in the assessment and prevalence of IGD, the etiology of the disorder, and the most important treatment methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Commercial video games have been played since the early 1970s, and gaming as a leisure time activity has become increasingly popular since their introduction, regardless of age and gender [1]. The Internet—in the form known today—emerged in the late 1980s and has expanded rapidly ever since [2]. Due to their psychologically rewarding features [3], it did not take long before reports of excessive video gaming and Internet use (in a way that is detrimental to the person’s life) began to appear in the psychological and medical literature [e.g., 4–6]. Throughout the 2000s, research interest in problematic Internet use and video gaming appeared to increase exponentially, and with the inclusion of Internet gaming disorder (IGD) in Section 3 of the latest (fifth) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-5; 7], research into the condition will most likely increase even further. Among video gaming and different Internet activities, online gaming appears to be associated with an increased risk of addiction [8, 9]; therefore, the majority of current research focuses on the negative consequences of this activity.

Based on the mostly anecdotal early findings, as well as on the qualitative and large-scale quantitative studies carried out more recently, symptoms and negative consequences can be very serious in extreme cases [10]. Although the amount of time players spend gaming has no diagnostic value in itself, gamers with IGD spend most of their time gaming and is detrimental to their physical and psychological well-being. Losing interest in and neglecting other activities can lead to a considerable decrease in work- or education-related performance, while their interpersonal relationships deteriorate or come to an end [10]. Problematic gamers are unable to control their excessive behavior even after they realize the problems it causes in their lives. When not gaming, they usually fantasize about gaming, and experience withdrawal-like symptoms such as irritability, restlessness, frustration, annoyance, and/or sadness. If they manage to cease gaming for a while, they usually restart the activity later with similar intensity. In severe cases, gamers ignore their basic biological needs (e.g., sleeping, eating, and personal hygiene) and may experience a variety of health problems such as gaining or losing weight, having dry or strained eyes, headaches, backaches, carpal tunnel syndrome, general fatigue, and/or exhaustion [10].

Defining Internet Gaming Disorder

Scientific interest in behavioral addictions has risen considerably over the last two decades [11]. This resulted in the creation of the “Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders” section in DSM-5 and the inclusion of gambling as a non-substance (i.e., behavioral) addiction for the first time [7]. Moreover, the Substance Use Disorder Workgroup decided to include another non-substance addiction in the “Emerging Measures and Models” section of the DSM-5 (i.e., Internet gaming disorder) after reviewing 250 related publications and concluding that, although there are no definitive conclusions, the problem deserves scientific attention due to the severity of its consequences reported in the literature [12]. While many other behavioral addictions (e.g., compulsive buying, work addiction, exercise addiction, sex addiction [hypersexuality]) were also candidates for inclusion, the workgroup concluded that research was relatively scarce in these domains and therefore, none of other non-substance addictions were included in DSM-5 [12, 7].

Although there is no firm agreement as to whether IGD is a genuine addiction [13–15], the inclusion of IGD appears to have been well received by most of the researchers and clinicians working in the field [16]. Nevertheless, there are three main concerns surrounding the inclusion. The most important criticism regarding the recognition of IGD as a bona fide behavioral addiction is that once addiction becomes a diagnostic label attached to behaviors other than gambling (that has a strong association with substance addictions), the term “addiction” may suffer potential depreciation because of its permissive nature [17, 18, 14]: “If every gratified craving from heroin to designer handbags is a symptom of ‘addiction,’ then the term explains everything and nothing” [18, 19]. In addition, some researchers argue that treatment models based on the theory of addiction might reduce the patients’ self-efficacy by teaching them they are not in control of their behavior making the recovery process more difficult [20]. Another potential negative consequence of the inclusion is that it might lead to the premature acceptance of IGD as a behavioral addiction [21, 22] and to the preconception that the proposed criteria are the “true” IGD criteria. This could hinder following efforts to create or test alternative explanatory models of the disorder (e.g., reward deficiency syndrome [23], or compensatory internet use [24]) and/or to critically evaluate each proposed criterion (that is actually the main purpose of the inclusion).

The nine IGD criteria as proposed in Section 3 of DSM-5 are the following: (i) preoccupation with Internet games; (ii) withdrawal symptoms when Internet gaming is taken away; (iii) tolerance—the need to spend increasing amounts of time engaged in Internet games; (iv) unsuccessful attempts to control the participation in Internet games; (v) loss of interests in previous hobbies and entertainment as a result of, and with the exception of, Internet games; (vi) continued excessive use of Internet games despite knowledge of psychosocial problems; (vii) deception of family members, therapists, or others regarding the amount of Internet gaming; (viii) use of Internet games to escape or relieve a negative mood; and (ix) jeopardizing or losing a significant relationship, job, or educational or career opportunity because of participation in Internet games [7]. Petry and her colleagues [12] pointed out that these criteria were mainly derived from an earlier report that proposed diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction (IA) using clinical samples in China [25]. Tao and his colleagues established their IA criteria based on their clinical experience and seven previous studies [26–32] that used gambling and substance use criteria from earlier versions of the DSM as their source. The DSM-5 criteria were also chosen and worded in a way to parallel the substance use and gambling disorder criteria [12].

While it is reasonable to parallel the IGD criteria with other existing addiction criteria in an attempt to clarify whether IGD is a behavioral addiction, some researchers in the field point out that Internet gaming is a distinctive behavior with unique features that should not be neglected. For instance, Kardefelt-Winther [33] claims that Internet gaming—unlike gambling or substance use—is one of the most popular leisure activities among today’s youth that spends great amounts of time gaming. Due to a substantial shift in the entertainment and communication practices of more recent generations, some of the IGD symptoms (e.g., preoccupation) considered as pathological earlier may be normative today [24]. Moreover, lots of the proposed IGD criteria have been heavily criticized.

Critiques of Certain IGD Criteria

King and Delfabbro [22] emphasized the complexity of the preoccupation criterion. In their view, preoccupation should not be assessed in terms of time but rather in terms of cognitive content. In other words, it is much more important to explore the adaptability of cognitions than the frequency of gaming-related thoughts. Tolerance and withdrawal are probably the most debated criteria because in the case of behavioral addictions, there is no physiological input only what the body can produce neurochemically by the behavior alone [20], and therefore the application of symptoms related to the physical effects of behaviors is debated. Nonetheless, Ko [34] noted that most players with IGD play so much that they could not increase their game time any further. Instead, they experience diminished levels of gaming satisfaction compared earlier playing sessions. If so, the criteria should be defined differently to adhere to the specific case of gaming. For instance, instead of the current phrasing (“Tolerance—the need to spend increasing amounts of time engaged in Internet games.”), the criterion could focus on the aforementioned decrease in satisfaction (e.g., “Tolerance—the individual experiences diminished levels of gaming satisfaction as a result of prolonged gaming activity.”).

In the case of gaming, withdrawal symptoms manifest as negative mood states (e.g., sadness) or as active symptoms (e.g., restlessness, irritability) [12]. Pies [18] points out that in addition to players’ self-report, it would be really important and timely to use physiological measures such as blood pressure or pulse rate to assess withdrawal symptoms. Another important point raised [18, 29] is that withdrawal should not be confused with the negative emotions that arise when gaming is suddenly stopped by an external force (e.g., an angry parent). Instead, it should refer to unpleasant symptoms experienced a couple of hours (up to 1–2 days) after ceasing gaming. Emotions felt after 2 weeks without gaming should be considered as craving rather than withdrawal [29]. On the other hand, withdrawal proved to be one of the three core criteria of pathological video-gaming (meaning that most of the measurement instruments included this symptom) according to a comprehensive literature review conducted by King and his colleagues [35••] prior to the publication of DSM-5 in May 2013.

The other controversial criterion is “deception of family members, therapists, or others regarding the amount of Internet gaming.” Deriving from DSM-IV pathological gambling criteria [36], it appears to be the weak link among the nine criteria symptoms. Tao and his colleagues [25] eliminated this symptom from their diagnostic instrument (the instrument that served as a bases for the DSM-5 criteria) since its frequency of incidence among their IA patients was much lower than of other symptoms. Similarly, deception had the lowest diagnostic accuracy and frequency of incidence among adult players with IGD in another Chinese study [37•].

In line with these findings, the aforementioned review by King and his colleagues [35••] reported few instruments where this criterion was included. The main argument against the suitability of this criterion for Internet gaming is that gaming usually takes place in the player’s home, therefore they would not be able to hide the activity even if they tried to [38]. Moreover, the players’ conditions of accommodation and personal relationships have a great influence over this criterion. For instance, bachelors who live alone may not need to give an account of their gaming to anybody, although their behavior might still be problematic.

Although not debated as much as the other criteria, using games to escape or relieve a negative mood showed low specificity (i.e., a considerable proportion of non-disordered gamers also played to escape problems) and therefore low diagnostic accuracy in two different studies [37•, 39•]. However, because the criterion was also experienced by the majority of disordered gamers, the two research groups did not propose its removal from the scale at this stage.

Critiques Regarding the Name and Content of IGD

Two additional highly debated topics are worth highlighting [40]. The first is related to the name of IGD. DSM-5 states that Internet use disorder, Internet addiction, or gaming addiction are also terms for the same construct (“Internet gaming disorder [also commonly referred to as Internet use disorder, Internet addiction, or gaming addiction] has merit as an independent disorder”; [7]). It is the present authors’ view—in accordance with the opinion of Griffiths and Pontes [40]—that this confusion regarding the names is highly problematic and has already had a negative influence over the unification of the field. While online gaming may be considered an Internet activity [10], the Internet is a medium through which many activities can be pursued (e.g., sending messages, sharing and getting information, shopping, gambling, viewing pornography, etc.). Therefore, even if we consider online gaming an Internet activity, Internet and gaming are certainly different constructs.

Moreover, empirical studies demonstrate that problematic Internet use and problematic online gaming are also different nosological entities [41•, 42, 43•]. In spite of the obvious difference between the two terms, online gaming addiction was often referred to as “Internet addiction” making it difficult to know exactly what the respective studies measured [35••]. For instance, in a Chinese study, the authors consistently referred to the patients having “Internet addiction disorder” (IAD), when at one point they also mentioned that “all (the patients) were addicted to game playing” [44]. Unfortunately, this frequent blending of the two terms has made the field confusing and puzzling. This has held the unification of the field back even more. Griffiths and Pontes [40] argue that one possible reason for using the two terms as synonyms might be that several studies used Young’s [31] Internet Addiction Test (IAT) to assess online gaming addiction. Another reason might be that researchers rarely are “gamers” themselves, and therefore have a different approach to what games really are and/or the medium in which they are played. While “gamers” may not consider online gaming (especially MMORPGs) an Internet activity, but rather as gaming per se; for researchers, the medium (i.e., Internet) may be more important [45].

The second highly debated topic refers to the content or object of IGD. DSM-5 states that (“Internet gaming disorder most often involves specific Internet games, but it could involve non-Internet computerized games as well, although these have been less researched”; [7]). In other words, the disorder is called Internet gaming disorder, but in reality it refers to any type of video games irrespective of the medium in which it is played (e.g., console, arcade, mobile device, personal computer, etc.). While several researchers argue that online game addiction should be viewed as a subtype of video game addiction than a subtype of Internet addiction [40, 46, 47] (because the Internet is only a medium that provides some additional features [i.e., social interaction] to the games), it is certainly misleading and thus problematic to use a name that excludes offline games by definition while still including them. The main reason why the Substance Use Disorder Work Group voted for the name Internet gaming disorder and not video game disorder was that online games appeared to be associated with the most serious problems [e.g., [8]. However, as many researchers have noted (particularly research carried out in the pre-internet 1990s), offline video games can also cause problems, therefore it is the task of future research to find the best name for the problem behavior.

Assessment and Prevalence

Being an emerging problem brought on by rapid technological development over the last few decades, it has always been a central question about how best to assess problematic/addictive use of video games. Even the earliest papers on Internet and/or video game addiction proposed instruments for assessment [e.g., 48, 31]. These have been fairly arbitrary, usually derived from existing DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling and/or substance dependence [36]. Since these early papers, many measurement instruments have been developed, all of them focusing on slightly different dimensions of IGD [35••]. Many of them seem to be evanescent, meaning that they have only been used in one study. Those used in more studies vary in terms of psychometric properties and general acceptance.

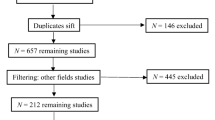

Although Young’s IAT [31] is the most widely used instrument both in the area of IAD and IGD, results regarding its psychometric properties (especially its underlying dimensionality) are highly controversial [45, 49]. According to a recent review [45], among the instruments measuring IGD (prior to inclusion in the DSM-5), the Game Addiction Scale for Adolescents [50], the Video Game Addiction Test [51], the Video Game Dependency Scale [8], the Problematic Online Game Use Scale [52], the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire [53], and the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire Short Form [54] appeared to be the most appropriate for assessing IGD.

However, the inclusion of new IGD criteria in Section 3 of DSM-5 has already led to the development of new assessment and diagnostic instruments. As mentioned earlier, the nine IGD criteria are only proposals that certainly need in-depth scrutiny (see the critiques above), and since they have been designed for clinical diagnosis, certainly need appropriate wording to be applicable in epidemiological studies as well. Since the inclusion in DSM-5, new instruments have already been published: the IGD-20 Test [55•] which is a 20-item test that reflects the nine criteria of IGD incorporated in the theoretical framework of the components model of addiction [56]; the IGDS-SF9 [57], a 9-item tool assessing the nine DSM-5 criteria on a 5-point Likert scale; and the Video Game Dependency Scale [CSAS; 58•], an 18-item scale adapted from a prior instrument (KFN-CSAS-II; 7) to cover of all 9 DSM-5 criteria, by 2 items each. In addition, Lemmens and his colleagues [39•] tested four different instruments measuring IGD: two polytomous scales (a 27-item and a 9-item version) and two dichotomous scales (also a 27-item and a 9-item version). Of all four instruments, the 9-item dichotomous scale appeared to be the most practical scale for diagnostic purposes.

Taking into consideration the suggested wording for the nine IGD criteria [12], the present authors also propose a new instrument comprising of ten items (Ten-Item Internet Gaming Disorder Test; IGDT-10) (see Appendix). The final DSM criterion (“Has jeopardized or lost a significant relationship, job, or educational or career opportunity because of participation in Internet games.”) was split into two criteria to address the two different aspects of this criterion: (i) risking or losing a significant relationship and (ii) a decrease in school or work performance. This distinction was considered important because decrease in performance appears to be much more frequent than risking or losing a significant relationship [39•, 58•] and therefore addressing them in separate criteria facilitates comprehension and responding.

Quite clearly, clinical studies and clinical validation of the existing instruments are very much needed, probably more important than developing additional new instruments. Large-scale questionnaire studies are suitable for assessing the severity and scale of the problem, but unlike clinicians using clinical interviews, they are certainly not capable of identifying the boundary between truly disordered (clinical) cases and less severe ones. Therefore, the most important goal of the field at the moment is to clinically validate the instruments that appear psychometrically sound.

Data regarding the prevalence of IGD is diverse due to the use of assessment tools with different theoretical background, different empirical development, and different cut-off values, as well as the use of different samples with different methodologies. To date, few nationally representative surveys have been conducted, and almost all of them have targeted adolescents. The prevalence rates were as follows: 1.7 % in Germany [8]; 4.1 % [59] and 4.2 % [60] in Norway, respectively; 4.6 % in Hungary [54]; 1.3 % [61] and 1.6 % [62] in the Netherlands, respectively (the former value obtained from a sample comprising of both adolescents and adults); 8.5 % in the USA [63]; and 9 % in Singapore [64].

Additionally, a cross-national European survey comprising seven countries [65] reported the following prevalence data: 0.6 % in Spain, 1 % in the Netherlands, 1.3 % in Romania, 1.6 % in Germany, 1.8 % in Iceland, 2 % in Poland, and 2.5 % in Greece. Prevalence of IGD was usually much higher for male adolescents than for females. To the authors’ knowledge, only two studies to date have estimated the prevalence of IGD in nationally representative samples using the criteria proposed by the DSM-5. Rehbein and his colleagues [58•] reported a prevalence rate of 1.16 % in a sample of German adolescents aged 13–18 years, while Lemmens and his colleagues [39•] used a representative sample of Dutch adolescents and adults, aged 13–40 years, reporting a prevalence rate of 5.4 %.

Etiology and Correlates

Similar to other addictions, the acquisition, development, and maintenance of IGD depends on the interplay between several factors: the structural characteristics of the video games, the gamer’s psychological (and probably genetic) characteristics, motivations for play, and the sociocultural context of gaming.

Among the structural characteristics of video games that contribute to gamers’ enjoyment [66–68], players being at risk of IGD report significantly higher enjoyment on highly time-consuming features such as managing game resources, earning points, leveling up, getting 100 % in the game, and/or getting meta-game rewards than casual gamers [69]. The cooperative elements or social features of online games were also found to be related to IGD [70, 69]. However, one of the most important game mechanisms is operant conditioning and the principle of the partial reinforcement effect. Games give instant and valuable rewards to the gamers but only intermittently. Therefore, gamers keep playing even in the absence of rewards convinced that another reward is “just around the corner” [71, 10]. This is similar to children who keep nagging their parents for toys or sweets, knowing that if they are persistent enough, their parents will eventually give in to their request.

No matter how “addictive” might games be, no gamer will develop IGD without their own predisposing risk and protective factors. Approximately, two decades of research has shed some light on several important psychological characteristics and comorbidities that appear to be associated with the development and maintenance of IGD. These include depressive symptoms, above average state and trait anxiety, social phobia, increased feeling of loneliness, inadequate self-regulation, low self-esteem, lower life satisfaction, decreased psychosocial well-being, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis, narcissistic personality, aggression [10], and psychopathology in general [72]. The most serious drawback of these findings is the correlational nature of the data collected. It is also unclear as to whether these characteristics are the causes or the consequences of IGD. There is great need for longitudinal studies that may shed light on the direction of causality. However, there is a high probability that there is a reciprocal relation between some of these factors and IGD as some longitudinal studies already suggest [64, 73].

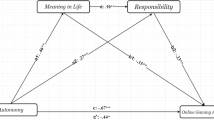

Gaming motives also appear to play a role in IGD. Several studies have found an association between the need to escape from real-life problems and difficulties (i.e., escape/escapism) and IGD [74–77], as well as specific achievement-related motives (i.e., competition, achievement, advancement, mechanics) and IGD [76, 77, 74]. The former association may be best interpreted in the theoretical framework of self-medication [78]. According to this framework, gamers with psychiatric distress use games as a coping strategy to improve their mood and/or attain emotional stability. Achievement-related motives on the other hand might be related to the lack of real-life achievements that are compensated by virtual victories and successes [79•]. In addition to direct association between certain motives and IGD, a recent study demonstrated the partial mediating effect of escape and competition motives between general distress and IGD [79•].

Treatment

Literature on different IGD treatment methods are scarce, especially studies assessing the efficacy of different intervention types. To date, no standard clinical treatment protocol exists, and treatment techniques are usually derived from the ones applied to substance use or gambling disorders. This includes online support forums, individual, group and family psychotherapeutic interventions, pharmacotherapy, the 12-step Minnesota-model, military drill (in military style boot camps), and addiction clinics with multimodal treatment programs have been reported in the literature [10, 80–84].

Among the psychotherapeutic treatment techniques, cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs) appear to be employed most often [85]. The CBT approach posits that faulty cognitions are the sources of maladaptive behaviors and psychological problems [86]. For instance, in the case of those undergoing treatment for IGD, virtual rewards may be perceived as being significantly more valuable than real-life relationships, hobbies, or a job. The goal of treatment is to induce behavioral change through identifying these faulty cognitions and replacing them with more healthy ones. Strategies to deal with everyday problems, time management, and self-regulation skills are often included too [87].

Pharmacological interventions are based on the assumption that IGD (like gambling disorder and substance use disorder) might share the same neurobiological mechanisms [88]. Medications such as bupropion, escitalopram, or methylphenidate have been used to treat IGD and/or comorbid psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety, ADHD) [82, 89•]. These studies have reported positive outcomes; however, the trials have several methodological shortcomings, and none of them assessed the long-term efficacy of the interventions. This is indispensable in making conclusions regarding the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments.

IGD is considered a main health issue by South-East Asian governments (e.g., China, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan), affecting mostly the male adolescents and young adults [7, 90]. In order to treat the problem, dozens of Internet addiction treatment centers and military style boot camps have been established across these countries [91, 82]. Unfortunately, the efficacy of the treatment programs provided in these clinics/camps is not known.

Summing-up, standardized and comprehensive methods of diagnosis (i.e., in addition to gaming frequency and IGD criteria, the context of gameplay, gaming motives, etc. should also be considered for diagnosis), standardized treatment protocols, and standardized methods to assess the efficacy of these interventions are necessary [85, 89•]. Not only should gaming frequency and IGD symptoms be assessed to determine posttreatment outcomes but also broader areas of benefit (e.g., the gamer’s functioning in work/school-related areas, their participation in leisure time activities, the quality of their interpersonal relationships, etc.) and factors that prevent relapse should be investigated. Due to the lack of rigor in such studies to date, none of the outlined intervention types have sufficient empirical support for treatment efficacy [89•].

Conclusions

Overall, it can be concluded that although the inclusion of IGD in the “Emerging Measures and Models” section of DSM-5 appears to have been well received by most in the gaming studies field, reaching a consensus will take a long time if it is possible at all. On one hand, research must now focus on the rigorous examination of each diagnostic criterion, preferably through clinical studies, large-scale empirical studies, cross-cultural studies, and in-depth qualitative inquiry (in order to find out which criteria are contextually valid in the case of video games; [33]). However, on the other hand, it must be highlighted that the behavioral addiction framework needs further testing and comparison with alternative models such as the reward deficiency syndrome [23] or the model of compensatory internet use disorder [24].

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Entertainment Software Association. Facts about the computer and video game industry. 2014. http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/ESA_EF_2014.pdf. Accessed 31 Jan 2015.

International Telecommunication Union. The world in 2014. ICT facts and figures. Geneva, Switzerland. 2014. http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2014-e.pdf. Accessed 31 Jan 2015.

Wallace P. The psychology of the Internet. Cambridge: University Press; 2001.

Keepers GA. Pathological preoccupation with video games. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:49–50.

Griffiths MD. Internet addiction: an issue for clinical psychology? Clin Psychol Forum. 1996;97:32–6.

Young KS. Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the Internet: a case that breaks the stereotype. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:899–902.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Text Revision. 5th ed. DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Rehbein F, Kleimann M, Mößle T. Prevalence and risk factors of video game dependency in adolescence: results of a German nationwide survey. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:269–77.

van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, van de Eijnden RJ, van de Mheen D. Compulsive internet use: the role of online gaming and other internet applications. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:51–7.

Király O, Nagygyörgy K, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Problematic online gaming. In: Rosenberg K, Feder L, editors. Behavioral addictions: criteria, evidence and treatment. New York: Elsevier; 2014. p. 61–95.

Demetrovics Z, Griffiths MD. Behavioral addictions: past, present and future. J Behav Addict. 2012;1:1–2.

Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, Lemmens JS, Rumpf HJ, Mossle T, et al. An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction. 2014;109:1399–406. doi:10.1111/add.12457.

Blaszczynski A. Internet use: in search of an addiction. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2006;4:7–9.

Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander BJ. "Computer addiction": a critical consideration. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:162–8.

Wood RTA. The problem with the concept of video game “addiction”: some case examples. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2008;6:169–78.

Griffiths MD, King DL, Demetrovics Z. DSM-5 internet gaming disorder needs a unified approach to assessment. Neuropsychiatry. 2014;4:1–4.

Starcevic V. Is Internet addiction a useful concept? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47:16–9.

Pies R. Should DSM-V designate “Internet addiction” a mental disorder? Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6:31.

Heller A. Short Takes. In: Boston Globe. 2008. http://www.boston.com/ae/books/articles/2008/11/02/short_takes_boston_globe/. Accessed 31 Jan 2015.

Van Rooij AJ, Prause N. A critical review of “Internet addiction” criteria with suggestions for the future. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:203–13.

Dowling NA. Issues raised by the DSM‐5 internet gaming disorder classification and proposed diagnostic criteria. Addiction. 2014;109:1408–9.

King DL, Delfabbro PH. The cognitive psychology of Internet gaming disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:298–308.

Blum K, Cull JG, Braverman ER, Comings DE. Reward deficiency syndrome. Am Sci. 1996;84:132–45.

Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;31:351–4.

Tao R, Huang XQ, Wang J, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Li M. Proposed diagnostic criteria for internet addiction. Addiction. 2010;105:556–64.

Beard KW, Wolf EM. Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2001;4:377–83.

Griffiths MD. Nicotine, tobacco and addiction. Nature. 1996;384:18.

Hollander E, Stein DJ. Clinical manual of impulse-control disorders. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CC, Chen SH, Yen CF. Proposed diagnostic criteria of Internet addiction for adolescents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:728–33.

Shapira NA, Goldsmith TD, Keck Jr PE, Khosla UM, McElroy SL. Psychiatric features of individuals with problematic internet use. J Affect Disord. 2000;57:267–72.

Young KS. Caught in the net: how to recognize the signs of internet addiction and a winning strategy for recovery. New York: Wiley; 1998.

Young KS. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1:237–44.

Kardefelt-Winther D. Meeting the unique challenges of assessing internet gaming disorder. Addiction. 2014;109:1568–70.

Ko CH. Internet gaming disorder. Curr Addict Rep. 2014;1:177–85.

King DL, Haagsma MC, Delfabbro PH, Gradisar M, Griffiths MD. Toward a consensus definition of pathological video-gaming: a systematic review of psychometric assessment tools. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:331–42. The paper reviews all the IGD measurement instruments developed since 2000, identifying the common points and shedding light on all the inconsistencies. Provides a very good overview of the assessment of IGD.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington: Author; 1994.

Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen SH, Wang PW, Chen CC, Yen CF. Evaluation of the diagnostic criteria of Internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5 among young adults in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:103–10. The paper aims to clinically validate the nine IGD criteria proposed in DSM-5 and the criteria of craving and irritability. Study participants and control participants underwent a diagnostic interview and completed standardized questionnaires. The findings suggest that ‘deceiving’, ‘escape’, and ‘craving’ have the lowest diagnostic accuracy and the proposed cut-off point of IGD criteria in the DSM-5 (i.e., fulfilling 5 or more criteria) is the best cut-off point for diagnosis of IGD.

King DL, Delfabbro PH. Video-gaming disorder and the DSM-5: some further thoughts. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47:875–6.

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Gentile DA. The internet gaming disorder scale. Psychol Assess. 2015. doi:10.1037/pas0000062. The authors tested four different instruments measuring IGD (as proposed in DSM-5): two polytomous scales (a 27-item and a 9-item version) and two dichotomous scales (also a 27-item and a 9-item version). Of all four instruments, the 9-item dichotomous scale appeared to be the most practical scale for diagnostic purposes. ‘Escape’ criterion showed the lowest diagnostic accuracy in this particular study.

Griffiths MD, Pontes H. Internet addiction disorder and internet gaming disorder are not the same. J Addict Res Ther. 2014;5:e124.

Király O, Griffiths MD, Urbán R, Farkas J, Kökönyei G, Elekes Z, et al. Problematic internet use and problematic online gaming are not the same: findings from a large nationally representative adolescent sample. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17:749–54. The paper examines the interrelationship and the overlap between Internet addiction disorder (IAD) and Internet gaming disorder (IGD) in a nationally representative sample of adolescent gamers. Based on the differences in terms of gender and preferred online activities IGD appears to be a conceptually different behavior than IAD.

Montag C, Bey K, Sha P, Li M, Chen YF, Liu WY et al. Is it meaningful to distinguish between generalized and specific Internet addiction? Evidence from a cross‐cultural study from Germany, Sweden, Taiwan and China. Asia‐Pacific Psychiatry. 2014

Rehbein F, Mößle T. Video game and internet addiction: is there a need for differentiation? Sucht. 2013;59:129–42. The paper suggests that Internet addiction disorder (IAD) and Internet gaming disorder (IGD) can be regarded as two distinct nosological entities. This differentiation is supported by differences in sociodemographic variables (i.e., gender, age) and types of online activities the adolescents engage in (i.e., playing video games, using social networking sites). The findings also suggest that subjective suffering seems to be higher among adolescents with IGD than among adolescents with IAD.

Huang XQ, Zhang CH, Li M, Wang J, Zhang Y, Tao R. Mental health, personality, and parental rearing styles of adolescents with Internet addiction disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:401–6.

Király O, Nagygyörgy K, Koronczai B, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Assessment of problematic internet use and online video gaming. In: Aboujaoude E, Starcevic V, editors. Mental health in the digital age: grave dangers, great promise. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. in press.

King DL, Delfabbro PH. Issues for DSM-5: video-gaming disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47:20–2.

Starcevic V. Video-gaming disorder and behavioural addictions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47:285–6.

Brenner V. Psychology of computer use: XLVII. Parameters of internet use, abuse and addiction: the first 90 days of the internet usage survey. Psychol Rep. 1997;80:879–82.

Laconi S, Rodgers RF, Chabrol H. The measurement of internet addiction: a critical review of existing scales and their psychometric properties. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:190–202.

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychology. 2009;12:77–95.

van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, van den Eijnden RJ, Vermulst AA, van der Mheen D. Video game addiction test (VAT): validity and psychometric characteristics. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15:507–11.

Kim MG, Kim J. Cross-validation of reliability, convergent and discriminant validity for the problematic online game use scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26:389–98.

Demetrovics Z, Urbán R, Nagygyörgy K, Farkas J, Griffiths MD, Pápay O, et al. The development of the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire (POGQ). PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36417.

Pápay O, Urbán R, Griffiths MD, Nagygyörgy K, Farkas J, Elekes Z, et al. Psychometric properties of the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire Short-Form (POGQ-SF) and prevalence of problematic online gaming in a national sample of adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16:340–8.

Pontes HM, Király O, Demetrovics Z, Griffiths MD. The conceptualisation and measurement of DSM-5 Internet gaming disorder: the development of the IGD-20 test. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e110137. The paper presents the rigorous psychometric development of a 20-item scale measuring IGD (called IGD-20 Test) reflecting the nine IGD criteria included in DSM-5 incorporated in the theoretical framework of the components model of addiction (i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse).

Griffiths MD. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Abus. 2005;10:191–7.

Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;45:137–43.

Rehbein F, Kliem S, Baier D, Mößle T, Petry NM. Prevalence of Internet Gaming Disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM‐5 criteria in a statewide representative sample. Addiction. 2015. doi:10.1111/add.12849. The study aims to estimate the prevalence rates of IGD based on DSM-5 IGD criteria and to assess how the specific criteria contribute to diagnosis. The prevalence rate of IGD in the nationally representative sample of German adolescents was 1.16%. Conditional inference trees showed that the criteria ‘give up other activities’, ‘tolerance’ and ‘withdrawal’ were most relevant for IGD diagnosis in this age group.

Mentzoni RA, Brunborg GS, Molde H, Myrseth H, Skouveroe KJ, Hetland J, et al. Problematic video game use: estimated prevalence and associations with mental and physical health. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:591–6.

Brunborg GS, Mentzoni RA, Melkevik OR, Torsheim T, Samdal O, Hetland J, et al. Gaming addiction, gaming engagement, and psychological health complaints among Norwegian adolescents. Media Psychology. 2013;16:115–28.

Haagsma MC, Pieterse ME, Peters O. The prevalence of problematic video gamers in the Netherlands. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15:162–8.

van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, Vermulst AA, van den Eijnden RJ, van de Mheen D. Online video game addiction: identification of addicted adolescent gamers. Addiction. 2011;106:205–12.

Gentile DA. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: a national study. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:594–602.

Gentile DA, Choo H, Liau A, Sim T, Li DD, Fung D, et al. Pathological video game use among youths: a two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2011;127:319–29.

Müller K, Janikian M, Dreier M, Wölfling K, Beutel M, Tzavara C, et al. Regular gaming behavior and internet gaming disorder in European adolescents: results from a cross-national representative survey of prevalence, predictors, and psychopathological correlates. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0611-2.

King DL, Delfabbro PH, Griffiths MD. Video game structural characteristics: a new psychological taxonomy. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2010;8:90–106.

Wood RTA, Griffiths MD, Chappell D, Davies MNO. The structural characteristics of video games: a psycho-structural analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7:1–10.

Westwood D, Griffiths MD. The role of structural characteristics in video-game play motivation: a Q-methodology study. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:581–5.

King DL, Delfabbro PH, Griffiths MD. The role of structural characteristics in problematic video game play: an empirical study. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2011;9:320–33.

Hull DC, Williams GA, Griffiths MD. Video game characteristics, happiness and flow as predictors of addiction among video game players: a pilot study. J Behav Addict. 2013;2:145–52.

Griffiths MD, Wood RTA. Risk factors in adolescence: the case of gambling, videogame playing, and the Internet. J Gambl Stud. 2000;16:199–225.

Starcevic V, Berle D, Porter G, Fenech P. Problem video game use and dimensions of psychopathology. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2011;9:248–56.

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Psychosocial causes and consequences of pathological gaming. Comput Hum Behav. 2011;27:144–52.

Kuss DJ, Louws J, Wiers RW. Online gaming addiction? Motives predict addictive play behavior in massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15:480–5.

Kwon J-H, Chung C-S, Lee J. The effects of escape from self and interpersonal relationship on the pathological use of internet games. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47:113–21.

Yee N. Motivations for play in online games. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9:772–5. doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9.772.

Zanetta Dauriat F, Zermatten A, Billieux J, Thorens G, Bondolfi G, Zullino D, et al. Motivations to play specifically predict excessive involvement in massively multiplayer online role-playing games: evidence from an online survey. Eur Addict Res. 2011;17:185–9.

Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–64.

Király O, Urbán R, Griffiths MD, Ágoston C, Nagygyörgy K, Kökönyei G, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and problematic online gaming: the mediating effect of gaming motivation. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e88. The paper tests the mediating role of online gaming motives between psychiatric distress and IGD. The results suggest that psychiatric distress is both directly and indirectly (via Escape and Competition motives) negatively associated with IGD, suggesting that exploring the motives of gamers can be helpful in the preparation of prevention and treatment programs.

Griffiths MD. Diagnosis and management of video game addiction. New directions in addiction treatment and prevention. 2008;12:27-41.

Griffiths MD, Meredith A. Videogame addiction and its treatment. J Contemp Psychother. 2009;39:247–53.

Huang XQ, Li MC, Tao R. Treatment of internet addiction. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:462–70.

Thorens G, Achab S, Billieux J, Khazaal Y, Khan R, Pivin E, et al. Characteristics and treatment response of self-identified problematic Internet users in a behavioral addiction outpatient clinic. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:78–81.

Jäger S, Müller KW, Ruckes C, Wittig T, Batra A, Musalek M, et al. Effects of a manualized short-term treatment of internet and computer game addiction (STICA): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:43.

King DL, Delfabbro PH, Griffiths MD. Clinical interventions for technology-based problems: excessive Internet and video game use. J Cogn Psychother. 2012;26:43–56.

Leahy RL. Cognitive therapy techniques: a practitioner's guide. New York: Guilford Press; 2003.

King DL, Delfabbro PH, Griffiths MD. Cognitive behavioral therapy for problematic video game players: conceptual considerations and practice issues. J Cybertherapy Rehabil. 2010;3:261–73.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Internet and gaming addiction: a systematic literature review of neuroimaging studies. Brain Sci. 2012;2:347–74.

King DL, Delfabbro PH. Internet gaming disorder treatment: a review of definitions of diagnosis and treatment outcome. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70:942–55. The authors systematically review current IGD treatment studies in terms of definitions of diagnosis and treatment outcomes. They conclude that IGD treatment literature is scarce and it has several methodological weaknesses, therefore it cannot be concluded that trialed IGD interventions confer a long-term therapeutic benefit.

Cha AE. In China, stern treatment for young internet 'Addicts'. In: The Washington Post. 2007. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/02/21/AR2007022102094.html. Accessed 31 Jan 2015.

Fackler M. In Korea, a Boot Camp Cure for Web Obsession. In: The New York Times. The New York Times Company. 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/18/technology/18rehab.html?pagewanted = all&_r = 0. Accessed 31 Jan 2015.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (grant numbers: K83884 and 111938).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest Orsolya Király and Mark D. Griffiths declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Zsolt Demetrovics acknowledges financial support of the János Bolyai Research Fellowship awarded by the Hungarian Academy of Science.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

iThenticate: 7%ok

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Technology and Addiction

Appendix

Appendix

Ten-Item Internet Gaming Disorder Test (IGDT-10)

Please read the statements below regarding video gaming. The questionnaire refers to VIDEO GAMES (both online and offline, played on any platform), but the reference to ‘game’ or ‘gaming’ is used for the sake of simplicity. Please indicate on the scale from 0 to 2 (Never, Sometimes, Often) to what extent, and how often, these statements applied to you over the PAST 12 MONTHS!

Never | Sometimes | Often | |

|---|---|---|---|

1. When you were not playing, how often have you fantasized about gaming, thought of previous gaming sessions, and/or anticipated the next game? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

2. How often have you felt restless, irritable, anxious and/or sad when you were unable to play or played less than usual? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

3. Have you ever in the past 12 month felt the need to play more often or played for longer periods to feel that you have played enough? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

4. Have you ever in the past 12 month unsuccessfully tried to reduce the time spent on gaming? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

5. Have you ever in the past 12 month played games rather than meet your friends or participate in hobbies and pastimes that you used to enjoy before? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

6. Have you played a lot despite negative consequences (for instance losing sleep, not being able to do well in school or work, having arguments with your family or friends, and/or neglecting important duties)? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

7. Have you tried to keep your family, friends or other important people from knowing how much you were gaming or have you lied to them regarding your gaming? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

8. Have you played to relieve a negative mood (for instance helplessness, guilt, or anxiety)? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

9. Have you risked or lost a significant relationship because of gaming? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

10. Have you ever in the past 12 month jeopardized your school or work performance because of gaming? | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Scoring: In order to measure the DSM-5 criteria items are recoded into a dichotomous format according to the following: answers “Never” and “Sometimes” are evaluated as the criterion is not met (0 point), while “Often” is evaluated as the criterion is met (1 point).

Important: Question 9 and 10 belong to the same criterion, that is, answer “Often” on either Item 9 or Item 10 (or both items) means only 1 point.

Evaluation: DSM-5 considers the case clinically relevant if five or more criteria are met.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Király, O., Griffiths, M.D. & Demetrovics, Z. Internet Gaming Disorder and the DSM-5: Conceptualization, Debates, and Controversies. Curr Addict Rep 2, 254–262 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0066-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0066-7