Abstract

The interaction between artificial intelligence and intellectual property rights (IPRs) is one of the key areas of development in intellectual property law. After much, albeit selective, debate, it seems to be gaining increasing practical relevance through intense AI-related market activity, an initial set of case law on the matter, and policy initiatives by international organizations and lawmakers. Against this background, Zurich University’s Center for Intellectual Property and Competition Law is conducting, together with the Swiss Intellectual Property Institute, a research and policy project that explores the future of intellectual property law in an AI context. This paper briefly describes the AI/IP Research Project and presents an initial set of policy recommendations for the development of IP law with a view to AI. The recommendations address topics such as AI inventorship in patent law; AI authorship in copyright law; the need for sui generis rights to protect innovative AI output; rules for the allocation of AI-related IPRs; IP protection carve-outs in order to facilitate AI system development, training, and testing; the use of AI tools by IP offices; and suitable software protection and data usage regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The interaction between artificial intelligence (AI) and intellectual property rights (IPRs) is one of the key areas of development in intellectual property law. After much, albeit selective, debate, it seems to be gaining increasing practical relevance through intense AI-related market activity, an initial set of case law on the matter, and policy initiatives by international organizations (e.g. WIPO, EPO) and lawmakers.

Against this background, Zurich University’s Center for Intellectual Property and Competition Law (CIPCO) is conducting, together with the Swiss Intellectual Property Institute (IPI),Footnote 1 a research and policy project (hereinafter the “AI/IP Research Project” or “Project”) that explores the future of intellectual property law in an AI context. This paper briefly describes the AI/IP Research Project (Sect. 2) and presents (Sect. 3) an initial set of policy and research recommendations (“Recommendations”) for the development of IP law with a view to AI. It concludes (Sect. 4) with a look at possible topics for additional recommendations. For a terminological and technical description of artificial intelligence,Footnote 2 and for further background to the Recommendations below, as well as for AI/IP aspects that they do not address, this paper refers to the rich existing literature.Footnote 3

2 The AI/IP Research Project

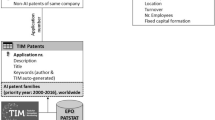

Initiated in 2021, the AI/IP Research Project aims at (i) gaining an overview of the current state of affairs in AI/IP, (ii) assessing issues crucial at the present stage, and (iii) deriving policy recommendations for how European jurisdictions, including Switzerland, should position themselves in international collaboration and in national law-making regarding AI/IP. Methodologically, the Project chooses a multi-component approach that has included, so far, mainly a comparative analysis of the AI/IP law situation – across the range of major IP rightsFootnote 4 – in various jurisdictions, the gathering of first-hand empirical evidence through stakeholder input (e.g. industry representatives, specialized counsel, members of state and supra-state IP administrations), and an interdisciplinary exchange with innovation economists and computer scientists specializing in AI. As a backbone of its 2021/2022 activities, besides desk research work, the Project conducted a series of workshopsFootnote 5 in which legal, economic and technical experts, as well as company representatives and other stakeholders, presented and discussed key AI/IP aspects.Footnote 6 Our warmest thanks go to all those who have participated and are participating in the Project.Footnote 7 Their support is invaluable in the attempt to further an appropriate IP law framework for AI. At its next stage, the Project will, inter alia, intensify the intra-disciplinary legal discourse with scholars working on AI from angles other than core IP law, e.g. data law, contract law, and liability law.

3 Policy Recommendations

We distinguish three types of Policy Recommendations: Implementation Recommendations intend to guide the next steps in law and policy-making. We think, based on previous discourse and experience, that their beneficial effects are likely enough to put them into practice. Consideration Recommendations describe courses which the law should probably take. Some further reflection and research seem, however, advisable before implementing them. Research Recommendations identify issues that research should address, to produce consideration recommendations on these matters as well.

3.1 Implementation Recommendations

3.1.1 Inventorship in Patent Law

3.1.1.1 Recommendation

The law should be amended to allow the designation of AI systems as inventors. Meanwhile, patent applications should be free to designate persons as “proxy inventors” while also describing the inventive activity of the AI system. There should be more disclosure on such inventive activity. AI systems’ innovative abilities must become part of the PHOSITA concept and related protectability thresholds.

Where an AI system generated inventive output without inventive human intervention, the patent application should be permitted to say so and name the AI system as the inventor, along with a natural person or legal entity who claims ownership of the patent application and a resulting patent.

Until legal rules have (where necessary) been changed to accommodate the above Recommendation, natural persons should – as a temporary workaround – be allowed to act and register as “proxy inventors”, as long as they disclose this role and the AI system for which they act as proxy. Such disclosure should be provided in the description.

More honest recognition of the increasingly innovative role AI systems play in invention processes, however, also calls for stricter requirements for patent applications to disclose details regarding the nature, extent, and mechanism of an AI system’s inventive contribution.

Furthermore, AI system abilities must become part of the PHOSITAFootnote 8 concept and related protectability thresholds. A potential raising of the protectability bar resulting therefrom is welcome as it mitigates the risk of AI patent thickets.

3.1.1.2 Background

The question of whether patent law can and should recognize AI systems as inventors, if they generate otherwise patentable technical solutions without an inventive contribution by humans, is arguably the most conspicuous issue in the current AI/IP landscape. Besides academic debate,Footnote 9 the multi-pronged DABUS litigation plays a key role as it probes into a range of the most important patent jurisdictions on whether their existing rules permit AI system inventorship. So far, the track record of patent applications based on the inventions (allegedly) made by DABUS is not a very successful one and the rejecting patent offices or courts seem right in finding that the currently applicable patent law rules are oriented to human, not AI inventorship.Footnote 10

De lege ferenda, however, at a forward-looking policy level, important reasons weigh in favour of patent applications that openly describe the role AI systems have played in the invention process. A need to definitively assess whether the human contribution to an invention, relative to the contribution made by an AI system, is sufficient to establish human inventorship, and thus patentability, unnecessarily harms legal certainty and uses patent office resources. It is one of the functions of the patent system to instruct the public about the progress of innovation and, thereby, to induce further innovation, for instance in the form of follow-on inventions. Necessitating patent applicants to disguise the true relation between human and AI contributions to an invention, because they must otherwise fear that their application will be rejected, hampers this function. Such impairment becomes even stronger where AI-generated inventions are not submitted for patenting at all but remain confined to the realm of trade secrets. In fact, industry participants in the Project state that companies do prefer trade secrets over patents for AI-generated inventions where they perceive a high risk of ending up – after having to disclose their invention in a patent application – without IP protection because the determinant role of their inventive AI systems, if admitted, prevents patentability.

Remarkably, these and further advantages of openness regarding inventive AI systems have made courts creative in searching for solutions even de lege lata, under the provisions of current patent law. The German Federal Patent Court (“Bundespatentgericht”) and the EPO Boards of Appeal now seem to accept a sort of proxy human inventorship. According to this concept, an application must still formally name a natural person as the inventor, but it can, at the same time, explain that the inventive acts were performed by an AI system.Footnote 11 Although unnecessarily complicated and formalistic, the proxy human inventor approach presents an acceptable transitional solution until patent laws can be changed as recommended here.

Even if this patent law reform occurs, it will not obviate the need to designate the natural – or possibly legal (cf. Sect. 3.2.1) – person who becomes the initial owner of the granted patent and who, consequently, acquires the rights and obligations related to this position. Our Recommendation does not advocate patent ownership of AI systems. Since innovative human activity cannot be the parameter for determining initial ownership of patents on purely AI-generated inventions, the law must develop a set of different criteria (cf. Sect. 3.3.2). This exercise is all the more worthwhile because its results are key for many an AI/IP setting: where increasing prowess and independence of AI systems render it difficult to assign legal rights to their output based on human inventorship, creatorship, or similar concepts, other parameters must step in to safeguard an allocation that is economically sound and apt to fulfil the goals of the IP system.

This is not to ignore the fact that a large part of the inventions made today and in the near future result (also) from a human contribution substantial enough to acknowledge human inventorship without difficulties. The pertinent part of the above Recommendation does not deal with AI-assisted inventions but with truly AI-generated ones. These hard cases may be rare – some would even say: non-existent – at present. But their relevance seems very likely to increase, and the law should be prepared by then.

Assessing the novelty of an invention against the state of the art researched with the help of AI systems, and only accepting steps as inventive which so appear from the perspective of a PHOSITA equipped with an ordinarily skilled AI system, will most probably raise the bar for patent protection.Footnote 12 In their contributions to the Project, some stakeholders voiced the concern that, as a result, only resourceful players, commanding exceptionally performant AI systems, may be able to acquire patents in the future. While we acknowledge the theoretical validity of this point, we do not see any empirical evidence that such a development is underway in larger sectors of the economy. Furthermore, it has always been the case that greater resources – such as laboratories with superior equipment, larger research departments, the ability to pay high wages to attract the best researchers, etc. – increased the chance of a market player to accumulate patents. In sum, we do not currently think that unlevel-playing-field concerns should prevent the integration of AI system capacities into the patentability assessment.

3.1.2 Human Authorship in Copyright Law

3.1.2.1 Recommendation

The principle of human authorship should prevail in copyright law – at least in the droit d’auteur systems. Hence, copyright protection should not be extended to works of literature and art created by an AI system without a human contribution even if they amount to a creation in the sense of copyright law. This result is achieved by applying the established criteria of human creation. At the same time, this allows for granting copyright protection for content that has been collectively created by an AI system and a natural person provided that the human contribution is sufficiently creative.

3.1.2.2 Background

Intellectual property law is traditionally based on the idea of one (or several) human creator(s). That is especially true for copyright law, at least for the droit d’auteur systems. In these systems, the idea of a human author is firmly rooted in many key provisions.

The human author plays a key role in the conditions for the protection of a work. According to settled case law of the ECJ, the concept of a work entails an original subject matter which is the author’s own intellectual creation.Footnote 13 Accordingly, there is no work without an author and such author must always be a natural person.Footnote 14 The situation is similar in Swiss law which only protects intellectual creations with an individual character (Art. 2(1) Copyright Act). The requirement of the intellectual creation means that only works created by natural persons can be protected by copyright.Footnote 15 The link of the intellectual character to a human author may be less direct but it is no less important; according to the key test, the requirement of individual character is met if no other individual would have created an identical or highly similar work.Footnote 16 The human being is also the key figure for copyright ownership as the original rightholder is always the author, i.e. the natural person who created the work.Footnote 17 In addition, droit d’auteur systems provide for a series of personality rights, such as the right to recognition as the author and the right to determine the author’s designation,Footnote 18 the right to decide on the first publication of the work,Footnote 19 the right to decide if the work may be altered and/or used to create a derivative work,Footnote 20 and the right to oppose a distortion of the work.Footnote 21 Finally, all copyright systems calculate the term of protection starting from the death of the author.Footnote 22

While some copyright systems have granted copyright protection for machine-generated content for years,Footnote 23 the droit d’auteur systems are hardly suitable to do so. A fundamental shift in these systems would be necessary to accommodate protection of machine-generated content by rethinking and adapting the provisions on the requirement of protection, the initial rightholder, the granting (and exercising) of personality rights and the duration and calculation of the term of protection. However, there are no convincing reasons why this should be done. While we acknowledge that there are some arguments for granting copyright protection to AI-generated works, these arguments seem rather weak. Most importantly, it may not necessarily be convincing to treat works that seem to be similarly “creative” in a fundamentally different way, just because one has been produced by a machine and the other by a human being. However, works of literature and art are public goods and granting exclusive rights to such goods requires a sound justification. Given that all other rationales for the justification of copyright protection (namely personality rights and the labour theory) are closely linked to human creators, the only potential rationale for granting copyright protection for machine-generated works is the need to provide incentives for creative activities. However, once an AI system has been developed, it can produce content such as text, images, music, films, and the like at almost zero marginal cost. While it may be important to grant some form of IP protection for the AI system, there is no need to incentivize the use of these systems by granting copyright protection to their output.Footnote 24

There are other instruments for protecting output that has been created in a fully automated manner and lawmakers (and courts) could improve such instruments, if necessary. Most importantly, the “copy paste” and use of AI-generated content may be captured by unfair competition law, namely by applying the general clause of most European unfair competition acts that allow to capture imitations and the copy-pasting of third-party content if certain conditions are met.Footnote 25 In Switzerland, Art. 5(c) Unfair Competition Act seems to be a good match. This provision captures all instances of taking over and exploiting another person’s marketable work product by means of a technical reproduction process without reasonable effort of the person or company that takes over and exploits the work product. Should unfair competition law prove to be insufficient to accommodate justified needs for protection, lawmakers could consider creating specific neighbouring rights for content generated by AI systems.Footnote 26 From today’s perspective, however, there seems to be no need for such new rights.Footnote 27 In addition, creative software output of AI systems – potentially including settings where an AI system creates another AI system – may be covered by the software protection regime envisaged in these Recommendations (cf. Sect. 3.3.1).

In addition, it is important to bear in mind that denying copyright protection to AI-generated content does not mean that the producer cannot exploit such content on the market. Most importantly, such content can be protected by access restrictions and other technical measures, e.g. digital watermarks, to ensure that others cannot use it without paying a remuneration.

3.2 Consideration Recommendations

3.2.1 Corporate IPRs

3.2.1.1 Recommendation

The law should consider allowing corporations and other legal entities to acquire initial ownership of (AI-generated) patents and patent-related IPRs (e.g. utility patents, but not copyrights), at least in cases of AI inventorship.

3.2.1.2 Background

The discussion whether legal entities should be able to acquire the right to a patent and – following the grant of the patent – initial patent ownership is not new. So far, and though dissenting (de lege ferenda) views always existed,Footnote 28 the prevailing response has been negative,Footnote 29 not least because today’s patent laws give much weight to a personalistic notion of inventorship, according to which there cannot be an invention without a (human) inventor.Footnote 30 When, however, an invention is generated by an AI system, this conception seems much less convincing. The assignment of legal rights and economic benefits relating to such inventions relies less on personalistic criteria. For instance, companies, and not their employees, will frequently bear the costs for building an inventive AI system and they, not their employees, will exercise legal and economic control over these systems. Insisting on human initial patent ownership in such settings risks distorting a coherent assignment of legal and economic rights to non-human inventions. The law should, therefore, consider relaxing the rules that allow for human initial patent ownership only.Footnote 31

3.2.2 Need for New IPRs Doubtful

3.2.2.1 Recommendation

Currently, there is no need to establish new sui generis IPRs for AI output. Neither current research insights nor current market realities suggest a need for new (sui generis) IPRs (including neighbouring rights) for innovative or creative AI output. Unless future research, including work done as part of the AI/IP project, proves the opposite, lawmakers should abstain from establishing such new types of IPRs.

Furthermore, there are currently no sound reasons for a two-tiered system of differing protection for human and AI inventions and creations. On the contrary, such a system seems prone to generate delimitation predicaments and to entice concealment or deliberate distortion of the genuine innovative process.

Such restraint does not exclude improvements of the current protection regime, for instance, in order to better accommodate software (including AI systems) produced by an AI system (cf. Sect. 3.3.1), the way data rights are allocated, or the framework for trade secret protection.

Should future AI systems generate inventive output at a high rate and in a process that clearly lacks human inventive contribution, the situation may have to be reconsidered. Patent-like protection for such output, which is however weaker than the protective level of current patents, may become a preferable mechanism for allocating exploitation and transaction rights while avoiding over-protection.

3.2.2.2 Background

In academic discourse, proposals have been made for new types of intellectual property rights to protect the innovative or creative output of AI.Footnote 32 Sufficient IPR protection for the AI systems that generate such output seems, on the other hand, less of a concern. Our Patent Law Inventorship Recommendation (cf. Sect. 3.1.1) helps to guarantee the structural availability of IPR protection for technical AI inventions. According to our Authorship in Copyright Law Recommendation (cf. Sect. 3.1.2), restricted copyright protection for creative AI output constitutes not a failure but a virtue of the IPR system. A consensus against the establishment of distinct protection systems for human and AI-generated innovations has already been formed.Footnote 33 Mainly for the reasons stated in the above Recommendation, we support this position. Regarding inventive/creative output or other instances of valuable output generated by AI systems without substantial, innovative human contributions, neither the AI/IP Project nor – to our knowledge – other empirical or economic research (cf. also Sect. 3.3.3) has proven current market failures or insufficient innovation incentives that necessitate the creation of new IPRs. Growing new plants in the already lush garden of IP rights comes at a cost – e.g. anti-commons problems,Footnote 34 transaction costs or interaction issues between the various IPRs – that should only be incurred based on solid evidence of their necessity. Putting another dent in the enthusiasm for new sui generis rights, none of the new IP rights introduced in the last 50 years has proven a real success. This applies, in particular, to the protection of databases through a sui generis rightFootnote 35 and the legal protection of topographies of semiconductor products.Footnote 36 Even though it seems premature to assess the impact of the new neighbouring right for the protection of press publications, the chances of success of this new IP right seem doubtful as well.Footnote 37

We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that this picture may change in the future. New ways of detecting and deciding, with sufficient certainty, whether a human or an AI system generated a particular innovation may remove some qualms regarding a two-pronged protection system for human and AI inventions and creations. Extending patent protection at its current level (duration, scope of exclusivity, etc.) to AI-generated inventions may become an unacceptable impairment of dynamic efficiency and freedom to do business, if previsions come true that powerful AI systems will swamp the markets with innovative output at high rates and high quality. Then – and only then – should the law consider conceptualizing new types of limited IP protection, mainly for technical inventions. Such IPRs could combine the transactional benefits of a clear allocation of rights,Footnote 38 incentivization for the creation and maintenance of high-quality AI-systems,Footnote 39 disclosure of innovations to the public, and – for instance, through suitable licensing mechanisms – balanced access to protected content by other market participants. Utility patents do not necessarily provide a blueprint for such AI-specific, “narrow” IPRs, but at least they show that varying levels of protection for technical inventions is a concept that is workable and familiar to the IP system.

3.2.3 Broadened Research Exemption

3.2.3.1 Recommendation

Subject to further research, IP and data law should likely stipulate clearer and more permissive protection carve-outs to facilitate development, training, and testing of AI systems.

The development, training, and testing of AI systems requires the processing of very large amounts of data. Given the extremely broad definition of personal data in data protection laws,Footnote 40 much of these data are to be qualified as personal data and their use is thus subject to the provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and other data protection laws. In many instances, the data used by AI systems are digital representations of works of literature and art. This is usually the case when AI systems are to recognise or produce text, images, music or films, and therefore need to be trained with corresponding copyright content. In addition, many data used by AI systems will be protected by the sui generis database right. Trade secret or patent protection, for instance, can also come into play. Using data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems may thus violate the provisions of the GDPR or infringe copyrights, the sui generis right in databases, or other intellectual property rights.

Patent and copyright laws, as well as other IP protection systems, contain provisions that allow the use of protected content for research and development, but it seems doubtful whether the existing exemptions are sufficiently broad and homogeneous across jurisdictions to allow for the desired use level of such content by AI systems.Footnote 41 The Database Directive, for instance, does not contain any research exemption for the sui generis right. European lawmakers should thus consider introducing broader research exemptions in copyright law, and creating a research exemption for the sui generis right in databases.Footnote 42

While the GDPR contains provisions that amount to a potentially quite broad research exemption,Footnote 43 it remains unclear if and to what extent this exemption can be applied to privilege the processing of personal data for the development, training, and testing of AI. Given the key importance of data (including personal data) and the lack of harm caused to data subjects by the processing of personal data in the development, testing, and training of AI systems as such (note though that harm may be caused to data subjects by using AI systemsFootnote 44), we recommend that the GDPR’s research exemption should be interpreted in a way that facilitates such processing. Ideally, this interpretation should be explicitly promoted in an Opinion of the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) to provide legal certainty.

3.2.3.2 Background

Today’s IP and data protection laws were developed prior to the rise of AI.Footnote 45 Although patent, copyright, and data protection laws contain research exemptions, it is unclear if and to what extent these provisions can capture the use of personal data and IP-protected content if the respective data are used for the development, training, and testing of AI systems.

Regarding copyright law, the two exceptions for text and data mining introduced by the Digital Single Market (DSM) DirectiveFootnote 46 may mitigate the problem. The mandatory exception, however, only covers uses for scientific research by research organisations and cultural heritage institutions, thus excluding text and data mining in a commercial context.Footnote 47 The non-mandatory exception that also applies to commercial uses only covers cases in which text and data mining has not been expressly preserved by the rightholder. The scope of these exceptions is therefore limited. Moreover, the DSM Directive does not mention the use of text and data by AI systems. It is therefore unclear whether the exceptions also cover the use of copyright content for the development, training, and testing of AI systems. The recently introduced research exemption of the Swiss Copyright Act is substantially broader, covering all research and development (including for commercial purposes) and all reproductions that are necessary for technical reasons. Its deliberately broad wording should also cover the use of copyright-protected content by AI systems, both in a research and in a commercial setting.

The sui generis right allows the maker of a database to prohibit the extraction and/or re-utilization of the whole or a substantial part of the contents of a database. However, insubstantial parts may be used by lawful users of the database. While this certainly limits the restrictions of the sui generis right with respect to the use of data by AI systems, one must assume that there are many cases in which it would be useful to extract and re-use all or substantial parts of a database. Thus, the sui generis right imposes relevant restrictions on the use of data by AI systems. As opposed to copyright law, the Database Directive does not even contain an exception for text and data mining. In consequence, adding a broad research exemption to the Directive that also covers the use of data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems seems to be key. Importantly, such an exemption would not confer a standalone right of access to the data contained in a database. It would merely allow the use of data for research purposes if access to such data has already been granted, most often on a contractual basis and against remuneration.

European data protection laws, especially the GDPR, create significant obstacles to the use of data by AI systems, such as the principle of data minimization and purpose limitation, as well as the need to provide a legal basis for the processing of personal data.Footnote 48 Additional barriers stem from restrictive rules on the transfer of personal data to third countries and the increasingly impractical distinction between personal and non-personal data. While the GDPR contains provisions that potentially amount to a quite broad research exemption,Footnote 49 it remains unclear if and to what extent this exemption can be applied to privilege the processing of personal data for the development, training, and testing of AI. However, a suitable application of the research exemption can only be a first step. As outlined below, further research is needed to develop a suitable data usage framework.Footnote 50 In addition, clear and comprehensive data access and/or data use rightsFootnote 51 should be established, regarding both personal and non-personal data, to facilitate the development, training, and testing of AI systems.

At the same time, protection carve-outs must not become a carte blanche for IPR infringement. Generative art (art with and through AI) is, for instance, a field in which legal rules need to carefully balance access to and protection of IPR-protected content. AI is a powerful tool for creating works such as films, music, or architectural designs. Such tools are already being offered to the general public for free. The conditions for use of such tools and their output (including sale as non-fungible tokens) vary greatly and can have important effects on the operating modes and business models of the artistic community. Some developers are not sufficiently aware of, or are not willing to abide by, copyright protection rules. Others miss out on advantageously structuring the use of their tools through contractual arrangements. Working, together with stakeholders, from this situation towards a more appropriate legal and factual framework for generative art constitutes a worthy task both for IP offices and for the general discourse on AI protection carve-outs.

3.3 Research Recommendations

3.3.1 New Software Protection Regime

3.3.1.1 Recommendation

Future research should develop a novel IP protection regime for software that could replace today’s two-tiered approach.

The current IP system does not provide a convincing protection regime for software. The interaction of its main instruments, copyright and patent protection, is far from ideal. The regime has evolved over time, driven by the approach to somehow incorporate software protection into the traditional IP system. However, software differs in important respects from both works of literature or art and from technical inventions. Fitting it into copyright and patent law thus necessitates many compromises. Software produced and employed by AI systems is a recent challenge of particular importance to today’s approach. Therefore, the development of AI systems makes it more urgent than ever to remedy the deficiencies of the current regime for software protection.

The dual system combining copyright and patent protection should be rethought and possibly replaced by a single IPR for software (including AI systems). Such a regime may combine a very limited sui generis protection (regarding both substance and duration) for unregistered software with a stronger protection for software registered in a software register. The granting of a strong IP right could come with (source code) disclosure requirements. Better tailored to promote innovation and to avoid overprotection, such a system may also allow for the closing of current protection loopholes, e.g. regarding complex, highly innovative modelling software.

Given the huge economic importance of software, the implementation of such far-reaching changes in its protection regime resembles open-heart surgery. These changes cannot be undertaken without thorough prior research and discussion. Such research must be interdisciplinary, involving not only legal scholars but also computer scientists and economists. All stakeholders’ (software developers, industry, IP offices, the open source community, and key user groups, etc.) views need to be collected and novel protection approaches need to be tested in a discourse with them.

Given the existing framework of IP treaties, a novel software protection regime could hardly replace the current system over night. But novel approaches could be introduced at a national and regional (e.g. EU) level alongside the existing regimes. If these approaches prove workable, they may well replace the current protection regimes de facto, namely if companies stop applying for software patents and enforcing copyrights. Traditional approaches for software protection may either continue to (formally) exist or be abandoned altogether at a later point in time.

3.3.1.2 Background

Software has always been a sort of outsider among the subject matters of the IP system. The protection regimes that are applied to computer programs were developed long before software even existed. As it seemed virtually impossible to create an entirely new IP right to capture software in the 1980s and 1990s, national lawmakers and international organisations had no choice but to accommodate software in the existing IP regime. The obvious choice was copyright as it came with a series of benefits, the most important ones arguably being that the existing international regime allowed for an almost worldwide protection without the need for application, examination, registration, and payment of fees. In addition, the inclusion of software in patent law was blocked (at least) for the member states of the European Patent Convention as Art. 52(2)(c) EPC states that programs for computers cannot be considered inventions. The “linguistic approach”, focussing on the expression of algorithms in the source code, permitted software to be treated similarly to works of literature and art,Footnote 52 thus allowing copyright protection. With partial amendments to copyright law, e.g. on decompilationFootnote 53 or shortened protection terms,Footnote 54 some steps were taken towards a software-specific protection regime, but without accomplishing this task.

Irrespective of this integration process, businesses also sought the benefits of patent protection for their software. In the US, such patents were granted on a relatively broad basis following a series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in Diamond v. Diehr in 1981,Footnote 55 and subsequent decisions by the Court of Appeal for the Federal Circuit.Footnote 56 Europe remained reluctant, given the provisions in the EPC that excluded patents for computer programs as such (Art. 52(2)(c) and (3) EPC). While patents were (and still are) unavailable for mere computer programs, they were eventually granted for so-called “computer-implemented inventions”.Footnote 57 Over time, the more permissive US and the more restrictive European approach have converged to a certain extent. Inter alia, the US system became more stringent, and moved much closer to the European approach, with the Supreme Court’s Alice decision.Footnote 58

As a result of these historical developments, software can be protected by both patents and copyrights in the major jurisdictions. While it is not uncommon for several IP rights to protect a given object – e.g. copyright, design, patent, and trade mark rights to protect the design of a car – it is quite unusual for a given subject matter category to be explicitly covered by more than one IP right. Not surprisingly, this two-tier system of protection leads to contradictory results. For instance, despite the expiry of patent protection after 20 years, previously patented software does not fall into the public domain but remains protected by copyright for a much longer period of time.

A major problem of the current software protection regime is the fact that neither copyright nor patent law are well suited for this subject matter. Software is different from both technical inventions and works of literature and art. IP protection granted to it should be keyed to these particularities. For example, many software products (e.g. operating systems) cannot be substituted by others because they have become de jure or de facto standards. Software products need to be integrated into a (usually pre-existing) framework of hardware and software, which requires interoperability that can only be ensured if application programming interfaces (API) are provided or – where necessary – lawfully developed through reverse engineering. In digital economies, software assumes a sort of infrastructure role for ever more products and services. Also, in view of these characteristics, the strong protection (duration, degree of exclusivity, etc.) granted by the combination of copyrights and patent rights seems problematic at least for certain types of software (e.g. update patches). Licensing transactions ensuring freedom to operate are hampered by difficulties in determining software ownership and by multi-owner IPR thickets. Fragmented statutory rules and market developments, such as the “open source” movement, have patched some of these issues. Others have led to highly complex and year-long proceedings before competition authorities.Footnote 59 A well-tailored protection framework, including built-in limitations that secure access rights where needed, promises many advantages over these makeshift approaches. It becomes all the more desirable with a view to AI systems consisting, in essential parts, of software and generating large-scale software output the protection status of which is far from evident.Footnote 60

While it seems that software developers and the industries producing and using software have learned to cope with the current software protection framework, important issues remain unresolved. Moreover, the mere fact that developers and the industry have learned to make the best of the current software protection regime in no way precludes that a much better system could be created, i.e. a system that leads to faster and cheaper innovation and raises fewer competition issues.

3.3.2 AI Inventorship and IPR Allocation Parameters

3.3.2.1 Recommendation

Future research should develop a comprehensive grid for the allocation of entitlements resulting from innovations generated by AI systems.

As a key consequence of loosening the ties between the generation of innovative output (by AI systems) and the ownership of resulting IPRs (by natural or legal persons), research must work out a more comprehensive grid for the sound allocation of IP entitlements resulting from innovations generated by AI systems. This concerns a broad range of IPRs (e.g. patents, utility patents, design rights, and new forms of software protection), as well as settings where complementary innovative activity is undertaken by AI systems and human individuals or teams.

3.3.2.2 Background

An appropriate allocation of AI output-related IPRs to natural or legal persons sets the conditions for achieving the IP system’s goals, particularly the incentivization of innovation and the fostering of IP transactions – licensing in particular, but for instance also the use of IP as collateral in M&A and venture capital transactions – which help to disperse and implement protected content. The conduct-steering effect of liability as well as clear responsibilities in the IP system’s self-protection through the enforcement of IPRs against infringing use are further allocation-related benefits. Allocating rights and responsibilities to AI systems themselves is not an option due to these systems’ lack of personality in the legal sense.

There is already some discussion about parameters for allocating IPRs resulting from AI innovation.Footnote 61 Among the main candidates are creatorship of or investment in the output-generating AI system, control over the system at the time of innovation, and responsibility for task and output selection (choice-making). Furthermore, some jurisdictions have adopted statutory rules that assign – be it for AI settings or at a more general level – initial IPR ownership to persons other than the factual inventor.Footnote 62 However, these allocation elements do not yet form a sufficiently comprehensive framework. The additional questions such a framework would have to answer are manifold. What, for instance, is the – possibly sector-specific – hierarchy or relative weight of several applicable allocation parameters? In case different persons fulfil different allocation criteria, does this always result in co-ownershipFootnote 63 or do certain allocation parameters (sometimes) outweigh others? For settings in which co-ownership turns out to be the result, are IP law’s present rules on co-ownership appropriate, even though there are no non-economic inventor/author rights to be protected? Assuming that certain groups of (co-)rightholders yield to requests that they waive their position, e.g. for fear of otherwise losing downstream clients,Footnote 64 should the law accept such contractual arrangements?

Arranging the answers to such questions into a suitable allocation regime requires profound research. Such research needs to include legal, economic and technological aspects, including an incentives analysis (cf. 3.3.3) for accommodating novel allocation approaches.

3.3.3 Revisit Incentivization Necessities and Ownership Approach

3.3.3.1 Recommendation

The IPR system must not mechanically extend its traditional incentivization rationale to innovative AI output. AI systems themselves do not require incentivization. Effective and efficient incentives for natural/legal persons to engage in the development and use of high-quality AI systems, as well as in the implementation of and transactions over their innovative output, need not necessarily parallel traditional IPR incentives for human innovativeness. Traditional notions of ownership may have to be rethought and protection may be oriented more towards securing monetary rewards and freedom to operate than towards non-economic ownership rights.

3.3.3.2 Background

Economists point out that incentivization of AI outputs as such may be unnecessary or even detrimental, whereas it may drive innovation and dissemination to incentivize the commercialization of such outputs (including transactions over them) and the development of AI systems that generate them.Footnote 65 In view of the potentially high innovative output of (future) AI systems, granting full-fledged IPRs to each such output may, in particular, generate overcompensation and excessive IPR thickets. Research, in which economics looms large, must therefore explore incentivization exigencies and dynamics in the AI innovation field. It is crucial to avoid the unwanted effects of over- or under-protection on dynamic efficiency. Such research must also explore whether, and in which ways, the growing relevance of AI systems and data change the role IPRs play for businesses, both in daily practice and at a strategic level.Footnote 66

3.3.4 Data Usage Framework

3.3.4.1 Recommendation

Future research should develop a legal framework focusing on access, sharing and usage of (personal and non-personal) data for the common good while providing a suitable protection of privacy and workable means to protect individuals against harm resulting from data processing.

Next step research should specify legal cornerstones for enhancing the access to, usage and sharing of (personal and non-personal) data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems. Topics include novel approaches to data (protection) law, common data spaces, data pools, interoperability requirements, technical standards regarding syntax and semantics of data, and the (non-)mandatory, sector-specific licensing of data portfolios to AI users/developers on a FRAND basis.

These approaches must apply both to personal and non-personal data since access to and use of both types of data are key conditions for the development, training, and testing of many AI systems. Further research is needed on whether and to what extent the usage of personal data by AI systems risks engendering an infringement of data protection laws or personality rights, such as the right to protection of privacy. A potential way forward could be an in-depth analysis of the scope of current research exemptions in data protection laws (particularly the GDPR) to assess if these exemptions can be applied broadly to cover the usage of personal data by AI systems. But research should also consider entirely novel approaches that go beyond the idea of an all-encompassing regulation of the processing of personal data (as in the GDPR) but rather provide a workable protection of privacy and means to protect individuals against harm resulting from the processing of personal data (e.g. manipulation and discrimination) while opening up the usage of personal data for the common good.Footnote 67

This research must include both an interdisciplinary and an intra-disciplinary component. Obviously, workable data transaction frameworks cannot be conceived without the input of computer and data scientists. But even from a purely legal perspective, there are manifold issues that need to be considered beyond IP and data law, such as contract, competition and procedural law. Equally, the analysis of pertinent business models promises to be very fruitful, including collaboration between holders of large data sets and controllers of powerful AI systems.

In addition to opening up access to and use of data, in-depth research is needed to clarify the legal consequences if an AI system has been developed, trained, or tested with data that have been accessed or used unlawfully. Should this “infect” the AI system in some way, even if the system does not contain the unlawfully used data? Should the consequences be the same regardless of whether the data were used for the development, the training, or the testing of an AI system? And, should it matter whether vast or small amounts of data have been used in an unlawful way – possibly even just a single data point?

3.3.4.2 Background

Data are a key resource for AI operations, especially for AI systems that are based on machine learning. But use of and access to data are often restricted for various reasons. While the use of non-personal data is much less regulated and thus largely permissible, European data protection laws, especially the GDPR, impose significant restrictions on the use of personal data, the most important ones being: The principle of data minimization which requires that the processing of personal data be adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which the data are processed;Footnote 68 this principle may inhibit the use of personal data for the training, and testing of an AI system. The principle of purpose limitation according to which data may only be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes;Footnote 69 often, personal data would be a great resource for the development and training of an AI system, but that system might have a purpose which is different from the purpose for which the data were collected, e.g. geo-localization data collected by telecom service providers that could be used to train an AI system that helps to fight traffic jams and to balance public transportation occupancy. A major barrier for the use of personal data by AI systems is that some data protection laws, namely the GDPR, require a basis for the lawfulness of any processing of personal data, the most important ones being the data subject’s consent,Footnote 70 an overriding legitimate interest of the controller,Footnote 71 the need to process personal data for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is a partyFootnote 72 or the need to process data for compliance with a legal obligation.Footnote 73 Although the range of possible reasons for the lawfulness of processing is quite broad, such a basis will often be lacking for the use of personal data for the development, training, and testing of AI systems.

Restrictions on access to data are another severe impediment. Companies are increasingly aware that they possess vast amounts of data that can be used in a productive way, e.g. for the training and testing of AI systems. This potential is tapped in a growing number of cases, either in house by the data holding company or through data transactions. In many other settings, though, data access and use fail. Some lawmakers, especially the EU, are enacting certain rules which aim at fostering data exchange and usage. For instance, the Open Data DirectiveFootnote 74 requires public sector bodies and public undertakings to make data available, including publicly funded, high-value research data. The Data Governance ActFootnote 75 should allow for the re-use of certain public sector data that cannot be made available as open data, e.g. health data. The Draft Data ActFootnote 76 will allow users of IoT devices to gain access to data generated by these devices and to share such data with third parties, thus mitigating their exclusive harvesting by initial data collectors and holders. In addition, the act will include means for public sector bodies to access and use, in exceptional circumstances, data held by the private sector. The Digital Markets ActFootnote 77 obliges gatekeepers to provide data access and portability in various ways. However, research will have to investigate whether these measures and their impact on business models generate sufficient data access for the development, training, and testing of AI.

3.3.5 Use of AI Tools by IP Offices

3.3.5.1 Recommendation

IP offices should strive to exploit the capacity of AI systems in their own operations. This may include the determination of whether an application fulfils the respective protectability requirements (e.g. novelty and inventive step). As a sound medium-term prospect, AI tools will not replace humans in the examination of IPR applications but will become one element of an interactive approach in which human and AI skills are combined to complement each other.

AI tools could help to establish more coherent decision-making within and across IP offices. At the same time, the digitization and automation of IP office processes must maintain, or should even improve, the procedural protection for applicants and further parties to their procedures. As part of such protection, IP offices should strive to render their AI tools transparent and explainable, to the extent possible and reasonable. This could include the establishment of a freely available AI tools database that enables applicants and their agents to improve the quality of their IP filing and IP management and even pre-test the chances of success of their applications.

IP offices should, among themselves, pursue an approach of transparency, insight-sharing and cooperation, which does not exclude friendly competition for benchmark solutions. WIPO may pioneer such an approach.

3.3.5.2 Background

AI can be a tool, and not only a subject, for the work of IP offices. In fact, a number of AI pertinent projects are already run by offices such as Singapore’s IPOS, UKIPO, IPI, WIPO, and EPO.Footnote 78 Much more would be possible, however, and IP offices should engage in intense, cooperative research and discussion on how to implement the above recommendation. More generally, AI has much potential to optimize administrative processes. By reaping this potential, IP office processes could become blueprints for other branches of public administration. Research topics include the identification of suitable AI application fields, e.g. automatic patent/design classification, harmonization of lists of goods and services, computer vision treatment of pictures and similar items in IPR applications, natural language processing of application content, machine translation of applications and prior art searches, and tailor-made AI systems, e.g. adversarial networks, for protectability assessments. In addition, hands-on concepts for integrating AI skills into the PHOSITA standard and similar tests could be developed and data pools for training IP office AI systems could be established, including data-sharing between offices/jurisdictions and the usability of other government agencies’ data. In its network of IP office representatives, the AI/IP Research Project has detected much interest in these topics and enthusiasm to pursue them cooperatively. The Project aims at becoming a catalyst for such cooperation.

4 Outlook

The Zurich AI/IP Group fully recognizes that the interplay between AI and IP involves many further aspects. At this stage, the Policy and Research Recommendations cannot specifically address all of them. This section presents a – very much non-exhaustive – list of additional AI/IP topics, which may also become a focus of the Group’s future work.

Patterns of AI innovativeness and creativeness How do AI systems actually go about innovating and creating, both in the field of technical inventions and in areas such as “generative art”, today and in the foreseeable future? This topic is highly interdisciplinary, likely even driven by non-legal, technical/IT disciplines.

Liability regime for IPR/data law infringements by AI systems For instance, the ramifications of the black-box nature of AI systems; ways to increase predictability of use of IPR-protected content by AI systems; ways to build IP law compliance into AI systems; consequences of AI systems processing data the use of which is (partially) unlawful, e.g. lack of a basis for the lawfulness of processing; partial switch to a liability rule regime instead of injunctions; parameters for allocating liability to be in sync with entitlement allocation rules; and the need for mandatory precautions (insurance, reserves, etc.) by small providers of AI systems.

Consistency of the broader legal framework for AI Lawmakers around the globe are working on solutions to address the challenges caused by the use of AI systems in general, beyond the aspect of AI and IP. Important proposals, such as the EU Commission’s draft AI Act, do not specifically address IP issues. AI-related changes to the IP system must aim at consistency with general AI regulation and potential sector-specific AI regulations. Documentation, notification, and disclosure obligations on AI system users present an example for an area where AI/IP considerations and general AI regulation may overlap.

Notes

Both institution and Office anonymized for the purposes of this submission.

We are fully aware that there are important differences between the systems we lump together under the term “artificial intelligence” and that there is an ongoing debate on how the term can be defined from the perspective of the law. We thank the reader for bearing with the generalizations made in this Project, permitting a more concise Recommendations document.

See, for instance, European Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on AI (2018); OECD High-Level General Definition of AI Systems, https://oecd.ai/en/wonk/a-first-look-at-the-oecds-framework-for-the-classification-of-ai-systems-for-policymakers; Chen et al. (2017); Krafft et al. (2020), p. 73 et seq.; Schuett (2021), p. 3 et seq.; Ongsulee (2017); Van Roy et al. (2019), p. 5 et seq.; Klinger et al. (2018), p. 4. Insights on the state of AI/IP affairs gained so far by the Project are canvassed, in greater detail, in Picht et al. (2023).

So far, the AI/IP discussion shows a certain, understandable focus on patent law. However, a conceptual, holistic policy project on AI/IP, such as the Project described here, must not overlook the important issues and developments in other areas of IP law, especially copyright and trade secrets law.

To the extent these workshops were conducted online, recordings are available at https://www.cipco.uzh.ch/de/veranstaltungen/IP-KI (all web sources last accessed 16 February 2023).

For an account of important findings thus gained, see Picht et al. (2023).

In particular Abraham Bernstein (University of Zurich), Alberto Russo (EUIPO), Alessandro Curioni (IBM), Alexander Klenner-Bajaja (EPO), Alicia Daly (WIPO), Anaic Cordoba (Swiss IPI), Angel Aledo Lopez (EPO), Beat Weibel (Siemens), Begonia Gonzalez Otero (Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition), representatives of the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore, Craig MacMillan (Canadian IPO), Daryl Lim (Penn State University), Emily Miceli (UKIPO), Felix Addor (Swiss IPI), Fernando Peregrino Torregrosa (EUIPO), Gaetan de Rassenfosse (EPFL), Hansueli Stamm (Swiss IPI), Heli Pihlajamaa (EPO), Ian Grimstead (UKIPO), Joseph Walton (UKIPO), Juan Bernabe-Moreno (IBM), Kate Gaudry (Kilpatrick Townsend), Martin Bader (University of St Gallen), Michael May (Siemens), Michael Schröder (ERNI AG), Naomi Häfner (University of St Gallen), Nicki Curtis (UKIPO), Peter R. Thomsen (Novartis), Pierre Olivier (UKIPO), Ryan Abbott (University of Surrey, DABUS Project), Sabrina Konrad (Swiss IPI), Samir Ghamir-Doudane (INPI), Sita Mazumder (Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts), Ulrike Till (WIPO) and Yann Ménière (EPO, MINES ParisTech).

Person having ordinary skills in the art (“Durchschnittsfachmann”).

For an overview of the litigation and discussion, see Picht, Brunner and Schmid (2023); for continuous updates on the DABUS applications and litigations, see also https://artificialinventor.com/patent-applications/.

Boards of Appeal of the European Patent Office, J 0008/20 – 3.1.01 and J 0009/20 – 3.1.01, 4.3.7; Federal Patent Court, 11 W (pat) 5/21, II.2.c.

ECJ decision of 13 November 2018, Levola Hengelo BV/Smilde Foods BV, C-310/17, para. 37; ECJ decision of 4 October 2011, Football Association Premier League, C-403/08 and C-429/08, para. 159; ECJ decision of 16 July 2009, Infopaq International, C-5/08, para. 39.

Swiss Federal Supreme Court, BGE 142 III 387, para. 3.1.; von Büren and Meer (2014), para. 178.

For European law, see: Sec. 7 of the German Copyright Act; Art. L111-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code (IPC); Sec. 10(1) of the Austrian Copyright Act. For Swiss law: Art. 6 Copyright Act.

For European law, see: Sec. 13 of the German Copyright Act; Art. L121-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code (IPC); Sec. 20(1) of the Austrian Copyright Act; Art. 8 of the Italian Copyright Statute. For Swiss law: Art. 9 Copyright Act.

For European law, see: Sec. 12(1) of the German Copyright Act; Art. L121-2 of the French Intellectual Property Code (IPC); Art. 12 of the Italian Copyright Statute. For Swiss law: Art. 9(2) Copyright Act.

For European law, see: Art. L121-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code (IPC); Sec. 21(1) of the Austrian Copyright Act; see also Sec. 23 of the German Copyright Act; Art. 18 of the Italian Copyright Statute. For Swiss law: Art. 11(1) Copyright Act.

For European law, see: Sec. 14 of the German Copyright Act; Art. L121-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code (IPC); Sec. 21(3) of the Austrian Copyright Act; Art. 25 of the Italian Copyright Statute. For Swiss law: Art. 11(2) Copyright Act.

Art. 7(1) Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (as amended on 28 September 1979).

E.g., UK (cf. Sec. 9(3), Sec. 12(7) and the definition of “computer-generated” in Sec. 178 CDPA, although some exceptions apply, cf. Sec. 79(2)(c) and Sec. 81(2) CDPA); Ireland (cf. Sec. 21(f), Sec. 30, and the definition of “computer-generated” in Sec. 2(1) of the Copyright and Related Works Act); Hong Kong (cf. Sec. 11(3), Sec. 17(6) and the definition of “computer-generated” in Sec. 198 of the Copyright Ordinance, although some exceptions apply, cf. Sec. 91(2)(c) and Sec. 93(2) of the Copyright Ordinance).

Note that this may be different if AI systems are used to produce inventions. Cf. Senftleben and Buijtelaar (2020), pp. 18–20, 23, who recommend to instead adopt a neighbouring rights approach.

Cf. Sec. 4(3) of the German Unfair Competition Act; Sec. 1(1)(1) of the Austrian Unfair Competition Act; regarding Scandinavian countries, Viken Monica (2020), passim.

See Sect. 3.2.2.

See, for Germany, BGH, Ia ZR 110/64 – Spanplatten; BGH, X ZR 54/67 – Wildverbissverhinderung; Busse and Keukenschrijver (2016), Sec. 6, note 17 et seq.; Mellulis (2015), Sec. 6, note 35; on German patent law before 1936, which allowed for corporate patents, Schmidt (2009), p. 234 et seq. For Switzerland, Botschaft, BBl 1967 II, p. 364; BGer 4A_78/2014; BPatGer O2012_001; Brehmi (2012), Art. 3, note 5 et seq.; Zuberbühler (2012). For the UK, Rhone-Poulenc Rorer International Holdings Inc v. Yeda Research & Development Co Ltd [2007] UKHL 43. For the US, Murphy (2012).

Cf., for instance, BGH, GRUR 1966, 558, 559 et seq.

Against corporate patent ownership in AI settings, Ann (2022), Sec. 1, note 25 et seq.; Sec. 19, notes 17–35.

Senftleben and Buijtelaar (2020), pp. 3, 19; Ramalho (2017), p. 16; Papastefanou (2020), p. 295; Lauber-Rönsberg and Hetmank (2019), p. 647. For parallel reflections in patent law, see Konertz and Schönhof (2018), p. 411; AIPPI German Delegation 2019, https://aippi.soutron.net/Portal/Default/en-GB/RecordView/Index/254, p. 18 et seq.

In general on them, Heller (2013).

Hoeren (2016), p. 790 et seq., with further references.

See, for instance, Merges (1994).

Cf. Sect. 3.3.3.

“Personal data means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person” (Art. 4(1) GDPR).

Cf. also Picht et al. (2023).

In recent case law, the ECJ may have (unintentionally) opened a backdoor to research use of databases by stating that “the main criterion for balancing the legitimate interests at stake must be the potential risk to the substantial investment of the maker of the database concerned, namely the risk that that investment may not be redeemed” (ECJ decision of 3 June 2021, CV-Online Latvia v. Melons, C-762/19, para. 44). According to the Court, the sui generis right in databases is only infringed in case of “a risk to the possibility of redeeming that investment through the normal operation of the database in question” (para. 47, emphasis added), which could be interpreted as a research exemption.

Namely, Art. 5(1)(b) GDPR and Art. 89 GDPR.

Cf., for instance, the Compas system used in the US to generate predictions about recidivism risks of a person accused of a crime, which was found to predict higher risks for black defendants (Liptak (2017)). In the Netherlands, a court halted the use of an automated system to find welfare fraud, finding that the system disproportionately targeted poorer people (Henley and Booth (2020)).

In fact, neither the provisions nor the recitals of the more recent regulations, such as the GDPR and the DSM Directive, even mention AI.

Arts. 3 and 4 Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC.

Geiger, Frosio and Bulayenko (2018), p. 10.

See Sect. 3.3.4.2.

Art. 5(1)(b) GDPR and Art. 89 GDPR.

See Sect. 3.3.4.2.

See Sect. 3.3.4.2.

See, for instance, Art. 4 WIPO Copyright Treaty; Art. 1 Directive 2009/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the legal protection of computer programs (EU Software Directive); Sec. 2(1)(1) German Copyright Act; Sec. 3(1)(b) UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act; Art. 2(3) Swiss Copyright Act.

E.g. Art. 6 Directive 2009/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the legal protection of computer programs (EU Software Directive); Sec. 69e German Copyright Act; Art. L122-6-1 (IV) French Intellectual Property Code (IPC); Sec. 50B UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act; Art. 21 Swiss Copyright Act.

E.g. Art. 29(2)(a) Swiss Copyright Act.

US Supreme Court decision of 3 March 1981, Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981).

Cf. in detail, Dragoni (2021).

On the concept and requirements, see EPO Examination Guidelines, Sec. G-II, 3.3 et seq., G-VII, 5.4.

US Supreme Court decision of 19 June 2014, Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014).

For example: ongoing proceedings regarding Apple Pay by the European Commission (EC press release of 2 May 2022, Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to Apple over practices regarding Apple Pay, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_2764 (accessed 20 September 2022)); proceedings regarding Google’s search engine by the European Commission between 2010 and 2017 (EC press release of 27 June 2017, Antitrust: Commission fines Google €2.42 billion for abusing dominance as search engine by giving illegal advantage to own comparison shopping service – Factsheet, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_17_1785 (accessed 20 September 2022)); proceedings regarding Microsoft’s Internet Explorer by the European Commission between 2007 and 2013 (BBC News, Microsoft fined by European Commission over web browser, 6 March 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-21684329); United States of America v. Microsoft Corporation, with subsequent settlement between Microsoft and the DOJ in late 2001 (implications discussed by Weinstein (2002)).

On the unavailability of copyright protection for AI-generated works, see Sect. 3.1.2.

On examples, such as the works made for hire doctrine (not AI-specific) or the UK and Irish legislation on ownership of AI-generated works (AI-specific), see Picht, Brunner and Schmid (2023).

Cf. for instance, on co-authorship of groups of choice-makers, Hugenholtz and Quintais (2019), pp. 1190, 1208 et seq.; AIPPI German Delegation, pp. 7, 12.

Cf. Hugenholtz and Quintais (2019), pp. 1190, 1209.

See, for instance, Rassenfosse et al. (2023).

Art. 5(1)(c) GDPR.

Art. 5(1)(b) GDPR.

Art. 6(1)(a) GDPR.

Art. 6(1)(f) GDPR.

Art. 6(1)(b) GDPR.

Art. 6(1)(c) GDPR.

Directive 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information.

Cf. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on European data governance (Data Governance Act) of 25 November 2020.

Cf. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act) of 23 February 2022.

Cf. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act) of 15 December 2020.

For an overview, see Picht et al. (2023).

References

Abbott R (2016) I think, therefore I invent: creative computers and the future of patent law. Boston Coll Law Rev 57(4):1079

Andermatt L (2008) SJZ 104:285

Ann C (2022) Patentrecht. Beck, Munich

Bonadio E, McDonagh L, Dinev P (2021) Artificial intelligence as inventor: exploring the consequences for patent law. Intellec Prop Q 1:48–66

Brehmi T (2012) In: Schweizer M, Zech H (eds) Patentgesetz (PatG). Stämpflis Handkommentar, Stämpfli, Berne

Broughton Micova S, Hempel F, Jacques S (2019) Protecting Europe’s content production from US giants. J Media Law 10(2):219–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/17577632.2019.1579296

Bullinger W (2022) Commentary on § 2 UrhG. In: Wandtke A, Bullinger W (eds) Urheberrecht, 6th ed. Beck, Munich

Burk DL (2021) AI patents and the self-assembling machine. Minn Law Re Headnotes 105:301–322

Busse R, Keukenschrijver A (2016) Patentgesetz, 8th ed. Beck, Munich

Chen M, Challita U, Saad W, Yin C, Debbah M (2017) Machine learning for wireless networks with artificial intelligence: a tutorial on neural networks. arxiv:1710.02913v2

de Cock Buning M (2016) Autonomous intelligent systems as creative agents under the EU framework for intellectual property. Eur J Risk Regul 7:310–322

Derclaye E, Husovec M (2022) Sui generis database protection 2.0: judicial and legislative reforms. LSE Working Papers. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4138436. Accessed 20 Sep 2022

Dornis TW (2020) Artificial creativity: emergent works and the void in current copyright doctrine. Yale J Law Technol 22:1–60

Dragoni M (2021) Software patent eligibility and patentability: an overview of the developments in Japan, Europe and the United States and an analysis of their impact on patenting trends. Stanford–Vienna Transatlantic Technology Law Forum Working Papers No 72, pp 28–36

Egloff W (2020) Commentary on Art. 6 CopA. In: Barrelet D, Egloff W (eds) Das neue Urheberrecht, 4th ed. Stämpfli, Berne

Fabian L (2019) Apariuz. Dike, Switzerland

Fabris D (2020) From the PHOSITA to the MOSITA: will “secondary considerations” save pharmaceutical patents from artificial intelligence? Int Rev Intellect Prop Compet Law 52:685–708

Fraser E (2016) Computers as inventors—legal and policy implications of artificial intelligence on patent law. SCRIPTed 33(3):305–333

Furman J, Seamans R (2018) AI and the economy. NBER Working Papers 24689

Geiger C, Bulayenko O, Frosio G (2017) The introduction of a neighbouring right for press publisher at EU level: the unneeded (and unwanted) reform. Eur Intellect Prop Rev 39(4):202–210

Geiger C, Frosio G, Bulayenko O (2018) The exception for text and data mining (TDM) in the proposed Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market – legal aspects. CEIPI Research Paper 2018-02, pp 1–24

Heller M (2013) The tragedy of the anticommons: a concise introduction and lexicon. Mod Law Rev 76:6

Henley J, Booth R (2020) Welfare surveillance system violates human rights, Dutch court rules. The Guardian, 5 February 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/feb/05/welfare-surveillance-system-violates-human-rights-dutch-court-rules. Accessed 20 Sep 2022

Hoeren T (2016) The semiconductor chip industry—the history, present and future of its IP law framework. IntRev Intellect Prop Comp Law (IIC) 47:763–796

Hug G (2012) Commentary on Art. 6 CopA. In: Müller B, Oertli R (eds) Urheberrechtsgesetz (URG), 2nd ed. Berne

Hugenholtz PB, Quintais J (2019) Neighbouring rights are obsolete. Int Rev Intellect Prop Comp Law (IIC) 50:1006–1011

Käde L (2021) KI-Systeme als Erfinder? Rdi 11:557–559

Klinger J, Mateos-Garcia J, Stathoulopoulos K (2018) Deep learning, deep change? Mapping the development of the artificial intelligence general purpose technology

Konertz R, Schönhof R (2018) Erfindungen durch Computer und künstliche Intelligenz – eine aktuelle Herausforderung für das Patentrecht? Zeitschrift für geistiges Eigentum ZGE 379–412

Krafft P, Young M, Katell M, Huang K, Bugingo G (2020) Defining AI in policy versus practice. In: Proceedings of the 2020 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES ’20), pp 72–78

Lauber-Rönsberg A, Hetmank S (2019) The concept of authorship and inventorship under pressure: does artificial intelligence shift paradigms? JIPLP 14(7):570–579. https://doi.org/10.1093/JIPLP/JPZ061

Lim D (2018) AI & IP: innovation & creativity in an age of accelerated change. Akron Law Review 52(3):813–875

Liptak A (2017) Sent to prison by a software program’s secret algorithms. The New York Times, 1 May 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/01/us/politics/sent-to-prison-by-a-software-programs-secret-algorithms.html. Accessed 20 Sep 2022

Loewenheim U, Pfeifer K-N (2020) Commentary on § 7 UrhG. In: Schricker G, Loewenheim U (eds) Urheberrecht, 6th ed. Beck, Munich

Mellulis K-J (2015) Benkard § 6 PatG. Beck, Munich

Ménière Y, Pihlajamaa H (2019) Künstliche Intelligenz in der Praxis des EPA. GRUR 332–336

Merges RP (1994) Of property rules, Coase, and intellectual property. 94 Colum. L. Rev. 2655

Murphy SL (2012) Determining patent inventorship: a practical approach. 13 N.C. J.L. & Tech. 215

Ongsulee P (2017) Artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning. 15th International Conference on ICT and Knowledge Engineering (ICT&KE)

Papastefanou S (2020) KI-gestützte Schöpfungsprozesse im geistigen Eigentum. WRP 290–296

Picht PG, Brunner V, Schmid R (2023) Artificial intelligence and intellectual property law: from diagnosis to action. JIPLP (forthcoming)

Ramalho A (2017) Will robots rule the (artistic) world? A proposed model for the legal status of creations by artificial intelligence systems. J Internet Law 21(1):12–25

Rassenfosse G, Jaffe A, Wassermann E (2023) AI-generated inventions: implications for the patent system (forthcoming, manuscript on file with the authors)

Schmidt A (2009) Erfinderprinzip und Erfinderpersönlichkeitsrecht im deutschen Patentrecht von 1877 bis 1936. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen

Schuett J (2021) Defining the scope of AI regulations. Legal Priorities Project Working Paper Series No 9

Senftleben M, Buijtelaar L (2020) Robot creativity: an incentive-based neighboring rights approach. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3707741. Accessed 20 Sep 2022

Simon BM (2013) The implications of technological advancement for obviousness. Mich Telecommun Technol Law Rev 19:331–337

Shemtov N (2019) A study on inventorship in inventions involving AI activity. Commissioned by the European Patent Office, February 2019

Staehelin A (2006) Der Arbeitsvertrag. In: Schmid J (ed) Kommentar zum schweizerischen Zivilrecht. Arts. 330b–355, Arts. 361–362 OR. Schulthess, Zurich

Thouvenin F (2019) Datenschutz auf der Intensivstation. Digma 206–216

Thouvenin F (2021) Informational self-determination: a convincing rationale for data protection law? JIPITEC 12:246–256

Thouvenin F (2023) Informationelle Selbstbestimmung: intuition, illusion, implosion (forthcoming)

Van Roy V, Vertesy D, Damioli G (2019) AI and robotics innovation. GLO Discussion Paper Series 433

Viken M (2020) The borderline between legitimate and unfair copying of products—a unified Scandinavian approach? Int Rev Intellect Prop Compet Law 51:1033–1061

von Büren R, Meer MA (2014) Der Werkbegriff. In: von Büren R, David L (eds) Schweizerisches Immaterialgüter- und Wettbewerbsrecht, II/1, Urheberrecht und verwandte Schutzrechte, 3rd ed. Helbing Lichtenhahn, Basel

Weinstein SN (2002) United States v. Microsoft Corp. Berkeley Technology Law Journal 17(1):273–294

Zuberbühler I (2012) Die Erschöpfung von Patentrechten. Stämpfli, Berne

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peter G. Picht is Chair for Economic Law, University of Zurich, Switzerland; Director at the Center for Intellectual Property and Competition Law (CIPCO), University of Zurich, Switzerland; Affiliated Research Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition in Munich, Germany.

Florent Thouvenin is Chair for Information and Communications Law, University of Zurich, Switzerland; Chair of the Executive Board of the Center for Information Technology, Society, and Law (ITSL), Zurich, Switzerland; Director of the Digital Society Initiative (DSI), University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article