Abstract

Background

Overreaching is the transient reduction in performance that occurs following training overload and is driven by an imbalance between stress and recovery. Low energy availability (LEA) may drive underperformance by compounding training stress; however, this has yet to be investigated systematically.

Objective

The aim of this study was to quantify changes in markers of LEA in athletes who demonstrated underperformance, and exercise performance in athletes with markers of LEA.

Methods

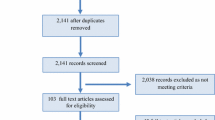

Studies using a ≥ 2-week training block with maintained or increased training loads that measured exercise performance and markers of LEA were identified using a systematic search following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Changes from pre- to post-training were analyzed for (1) markers of LEA in underperforming athletes and (2) performance in athletes with ≥ 2 markers of LEA.

Results

From 56 identified studies, 14 separate groups of athletes demonstrated underperformance, with 50% also displaying ≥ 2 markers of LEA post-training. Eleven groups demonstrated ≥ 2 markers of LEA independent of underperformance and 37 had no performance reduction or ≥ 2 markers of LEA. In underperforming athletes, fat mass (d = − 0.29, 95% confidence interval [CI] − 0.54 to − 0.04; p = 0.02), resting metabolic rate (d = − 0.63, 95% CI − 1.22 to − 0.05; p = 0.03), and leptin (d = − 0.72, 95% CI − 1.08 to − 0.35; p < 0.0001) were decreased, whereas body mass (d = − 0.04, 95% CI − 0.21 to 0.14; p = 0.70), cortisol (d = − 0.06, 95% CI − 0.35 to 0.23; p = 0.68), insulin (d = − 0.12, 95% CI − 0.43 to 0.19; p = 0.46), and testosterone (d = − 0.31, 95% CI − 0.69 to 0.08; p = 0.12) were unaltered. In athletes with ≥ 2 LEA markers, performance was unaffected (d = 0.09, 95% CI − 0.30 to 0.49; p = 0.6), and the high heterogeneity in performance outcomes (I2 = 84.86%) could not be explained by the performance tests used or the length of the training block.

Conclusion

Underperforming athletes may present with markers of LEA, but overreaching is also observed in the absence of LEA. The lack of a specific effect and high variability of outcomes with LEA on performance suggests that LEA is not obligatory for underperformance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, Fry A, Gleeson M, Nieman D, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European college of sport science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):186–205.

Bellinger P. Functional overreaching in endurance athletes: a necessity or cause for concern? Sport Med. 2020;50(6):1059–73.

King NA, Lluch A, Stubbs RJ, Blundell JE. High dose exercise does not increase hunger or energy intake in free living males. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51(7):478–83.

Drenowatz C, Eisenmann JC, Carlson JJ, Pfeiffer KA, Pivarnik JM. Energy expenditure and dietary intake during high-volume and low-volume training periods among male endurance athletes. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37(2):199–205.

Loucks AB, Kiens B, Wright HH. Energy availability in athletes. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(Suppl. 1):S7-15.

Nattiv A, Loucks AB, Manore MM, Sanborn CF, Sundgot-Borgen J, Warren MP. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(10):1867–82.

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the female athlete triad-relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):491–7.

Elliott-Sale KJ, Tenforde AS, Parziale AL, Holtzman B, Ackerman KE. Endocrine effects of relative energy deficiency in sport. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(4):335–49.

McCall LM, Ackerman KE. Endocrine and metabolic repercussions of relative energy deficiency in sport. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2019;9:56–65.

Dipla K, Kraemer RR, Constantini WW, Hackney AC. Relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S): elucidation of endocrine changes affecting the health of males and females. Hormones (Athens). 2021;20(1):35–47.

Schaal K, VanLoan MD, Hausswirth C, Casazza GA. Decreased energy availability during training overload is associated with non-functional overreaching and suppressed ovarian function in female runners. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(10):1179–88.

Schaal K, Tiollier E, Le Meur Y, Casazza G, Hausswirth C. Elite synchronized swimmers display decreased energy availability during intensified training. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2017;27(9):925–34.

Costill DL, Flynn MG, Kirwan JP, Houmard JA, Mitchell JB, Thomas R, et al. Effects of repeated days of intensified training on muscle glycogen and swimming performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20(3):249–54.

Vanheest JL, Rodgers CD, Mahoney CE, De Souza MJ. Ovarian suppression impairs sport performance in junior elite female swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(1):156–66.

Stellingwerff T, Heikura IA, Meeusen R, Bermon S, Seiler S, Mountjoy ML, et al. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): shared pathways, symptoms and complexities. Sport Med. 2021;51(11):2251–80.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Bell L, Ruddock A, Maden-Wilkinson T, Rogerson D. Overreaching and overtraining in strength sports and resistance training: a scoping review. J Sports Sci. 2020;38(16):1897–912.

De Pauw K, Roelands B, Cheung SS, de Geus B, Rietjens G, Meeusen R. Guidelines to classify subject groups in sport-science research. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2013;8(2):111–22.

Decroix L, De Pauw K, Foster C, Meeusen R. Guidelines to classify female subject groups in sport-science research. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016;11(2):204–13.

Gordon CM, Ackerman KE, Berga SL, Kaplan JR, Mastorakos G, Misra M, et al. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(5):1413–39.

Melin AK, Heikura IA, Tenforde A, Mountjoy M. Energy availability in athletics: health, performance, and physique. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019;29(2):152–64.

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, et al. Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) clinical assessment tool (CAT). Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(7):421–3.

Melin A, Tornberg ÅB, Skouby S, Faber J, Ritz C, Sjödin A, et al. The LEAF questionnaire: a screening tool for the identification of female athletes at risk for the female athlete triad. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):540–5.

Areta JL, Taylor HL, Koehler K. Low energy availability: history, definition and evidence of its endocrine, metabolic and physiological effects in prospective studies in females and males. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2021;121(1):1–21.

Strock NCA, Koltun KJ, Southmayd EA, Williams NI, De Souza MJ. Indices of resting metabolic rate accurately reflect energy deficiency in exercising women. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2020;30(1):14–24.

Torstveit MK, Fahrenholtz IL, Stenqvist TB, Sylta O, Melin A. Within-day energy deficiency and metabolic perturbation in male endurance athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(4):419–27.

Trexler ET, Smith-Ryan AE, Norton LE. Metabolic adaptation to weight loss: implications for the athlete. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11(1):1–7.

Papageorgiou M, Elliott-Sale KJ, Parsons A, Tang JCY, Greeves JP, Fraser WD, et al. Effects of reduced energy availability on bone metabolism in women and men. Bone. 2017;105:191–9.

Koehler K, Hoerner NR, Gibbs JC, Zinner C, Braun H. Low energy availability in exercising men is associated with reduced leptin and insulin but not with changes in other metabolic hormones. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(20):1921–9.

Kojima C, Ishibashi A, Tanabe Y, Iwayama K, Kamei A, Takahashi H, et al. Muscle glycogen content during endurance training under low energy availability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52(1):187–95.

Ishibashi A, Kojima C, Tanabe Y, Iwayama K, Hiroyama T, Tsuji T, et al. Effect of low energy availability during three consecutive days of endurance training on iron metabolism in male long distance runners. Physiol Rep. 2020;8(12):1–9.

Loucks AB, Thuma JR. Luteinizing hormone pulsatility is disrupted at a threshold of energy availability in regularly menstruating women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(1):297–311.

Zanker CL, Swaine IL. Responses of bone turnover markers to repeated endurance running in humans under conditions of energy balance or energy restriction. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;83(4–5):434–40.

Ishibashi A, Kojima C, Kamei A, Iwayama K, Tanabe Y, Kazushige G, et al. Effect of low energy availability during three consecutive days of endurance training on iron metabolism in male long distance runners. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2018;50(5S):461.

Badenhorst CE, Black KE, O’Brien WJ. Hepcidin as a prospective individualized biomarker for individuals at risk of low energy availability. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019;29(6):671–81.

Tornberg ÅB, Melin A, Koivula FM, Johansson A, Skouby S, Faber J, et al. Reduced neuromuscular performance in amenorrheic elite endurance athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(12):2478–85.

Ding J-H, Sheckter CB, Drinkwater BL, Soules MR, Bremner WJ, Seattle W. High serum cortisol levels in exercise-associated amenorrhea. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:530–4.

Hilton LK, Loucks AB. Low energy availability, not exercise stress, suppresses the diurnal rhythm of leptin in healthy young women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278(1):43–9.

Dubuc GR, Phinney SD, Stern JS, Havel PJ. Changes of serum leptin and endocrine and metabolic parameters after 7 days of energy restriction in men and women. Metabolism. 1998;47(4):429–34.

Loucks AB, Heath EM. Induction of low-T3 syndrome in exercising women occurs at a threshold of energy availability. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(3):817–23.

Wong HK, Hoermann R, Grossmann M. Reversible male hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to energy deficit. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2019;91(1):3–9.

Ihle R, Loucks AB. Dose-response relationships between energy availability and bone turnover in young exercising women. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(8):1231–40.

Johnstone AM, Murison SD, Duncan JS, Rance KA, Speakman JR. Factors influencing variation in basal metabolic rate include fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and circulating thyroxine but not sex, circulating leptin, or triiodothyronine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(5):941–8.

Lippi G, De Vita F, Salvagno GL, Gelati M, Montagnana M, Guidi GC. Measurement of morning saliva cortisol in athletes. Clin Biochem. 2009;42(9):904–6.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Sterne JA, Egger M, Moher D. Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane B Ser. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. p. 298–333.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane; 2021.

Von Hippel PT. The heterogeneity statistic I2 can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):1–8.

Flynn MG, Pizza FX, Boone JB, Andres FF, Michaud TA, Rodriguez-Zayas JR. Indices of training stress during competitive running and swimming seasons. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15(1):21–6.

Flynn MG, Carroll KK, Hall HL, Bushman BA, Gunnar Brolinson P, Weideman CA. Cross training: indices of training stress and performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(2):294–300.

Franchini E, Julio UF, Panissa VLG, Lira FS, Gerosa-Neto J, Branco BHM. High-intensity intermittent training positively affects aerobic and anaerobic performance in judo athletes independently of exercise mode. Front Physiol. 2016;7:268.

Gastmann U, Petersen KG, Bocker J, Lehmann M. Monitoring intensive endurance training at moderate energetic demands using resting laboratory markers failed to recognize an early overtraining stage. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 1998;38(3):188–93.

Hackney AC, Hooper DR. Low testosterone: Androgen deficiency, endurance exercise training, and competitive performance. Physiol Int. 2019;106(4):379–89.

Häkkinen K, Keskinen KL, Alén M, Komi PV, Kauhanen H. Serum hormone concentrations during prolonged training in elite endurance-trained and strength-trained athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1989;59(3):233–8.

Hoogeveen AR, Zonderland ML. Relationships between testosterone, cortisol and performance in professional cyclists. Int J Sports Med. 1996;17(6):423–8.

Iguchi J, Kuzuhara K, Katai K, Hojo T, Fujisawa Y, Kimura M, et al. Seasonal changes in anthropometric, physiological, nutritional and performance factors in collegiate rowers. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34(11):3225–31.

Jürimäe J, Mäestu J, Jürimäe T. Leptin as a marker of training stress in highly trained male rowers? Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;90(5–6):533–8.

Jürimäe J, Purge P, Jürimäe T. Adiponectin and stress hormone responses to maximal sculling after volume-extended training season in elite rowers. Metabolism. 2006;55(1):13–9.

Bachero-Mena B, Pareja-Blanco F, González-Badillo JJ. Enhanced strength and sprint levels, and changes in blood parameters during a complete athletics season in 800 m high-level athletes. Front Physiol. 2017;8:637.

Koundourakis NE, Androulakis N, Spyridaki EC, Castanas E, Malliaraki N, Tsatsanis C, et al. Effect of different seasonal strength training protocols on circulating androgen levels and performance parameters in professional soccer players. Hormones (Athens). 2014;13(1):104–18.

Lakhdar N, Ben Saad H, Denguezli M, Zaouali M, Zbidi A, Tabka Z, et al. Effects of intense cycling training on plasma leptin and adiponectin and its relation to insulin resistance. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34(3):229–35.

Lee C-L, Hsu W-C, Cheng C-F. Physiological adaptations to sprint interval training with matched exercise volume. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(1):86–95.

Lehmann M, Gastmann U, Petersen KG, Bachl N, Seidel A, Khalaf AN, et al. Training-overtraining: performance, and hormone levels, after a defined increase in training volume versus intensity in experienced middle- and long-distance runners. Br J Sports Med. 1992;26(4):233–42.

Lehmann M, Knizia K, Gastmann U, Petersen KG, Khalaf AN, Bauer S, et al. Influence of 6-week, 6 days per week, training on pituitary function in recreational athletes. Br J Sports Med. 1993;27(3):186–92.

Lopez Calbet JA, Navarro MA, Barbany JR, Garcia Manso J, Bonnin MR, Valero J. Salivary steroid changes and physical performance in highly trained cyclists. Int J Sports Med. 1993;14(3):111–7.

Mackinnon LT, Hooper SL, Jones S, Gordon RD, Bachmann AW. Hormonal, immunological, and hematological responses to intensified training in elite swimmers. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1997;29(12):1637–45.

Mäestu J, Jürimäe J, Jürimäe T. Hormonal reactions during heavy training stress and following tapering in highly trained male rowers. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35(2):109–13.

Mäestu J, Jürimäe J, Jürimäe T. Hormonal response to maximal rowing before and after heavy increase in training volume in highly trained male rowers. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2005;45(1):121–6.

Maresh CM, Armstrong LE, Bergeron MF, Gabaree CL, Hoffman JR, Hannon DR, et al. Plasma cortisol and testosterone responses during a collegiate swim season. J Strength Cond Res. 1994;8(1):1–4.

Bellinger P, Desbrow B, Derave W, Lievens E, Irwin C, Sabapathy S, et al. Muscle fiber typology is associated with the incidence of overreaching in response to overload training. J Appl Physiol. 2020;129(4):823–36.

Miloski B, De Freitas VH, Nakamura FY, De Nogueira FCA, Bara-Filho MG. Seasonal training load distribution of professional futsal players: effects on physical fitness, muscle damage and hormonal status. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(6):1525–33.

Mujika I, Chatard JC, Padilla S, Guezennec CY, Geyssant A. Hormonal responses to training and its tapering off in competitive swimmers: relationships with performance. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1996;74(4):361–6.

Muscella A, Vetrugno C, Spedicato M, Stefàno E, Marsigliante S. The effects of training on hormonal concentrations in young soccer players. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(11):20685–93.

Ndon JA, Snyder AC, Foster C, Wehrenberg WB. Effects of chronic intense exercise training on the leukocyte response to acute exercise. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13(2):176–82.

Nuuttila O-P, Nikander A, Polomoshnov D, Laukkanen JA, Hakkinen K. Effects of HRV-guided vs. predetermined block training on performance, HRV and serum hormones. Int J Sports Med. 2017;38(12):909–20.

Papacosta E, Gleeson M, Nassis GP. Salivary hormones, IGA, and performance during intense training and tapering in judo athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(9):2569–80.

Passelergue PA, Lac G. Salivary hormonal responses and performance changes during 15 weeks of mixed aerobic and weight training in elite junior wrestlers. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(11):3049–58.

Petibois C, Déléris G. Alterations of lipid profile in endurance over-trained subjects. Arch Med Res. 2004;35(6):532–9.

Rämson R, Jürimäe J, Jürimäe T, Mäestu J. Behavior of testosterone and cortisol during an intensity-controlled high-volume training period measured by a training tast-specific test in men rowers. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(2):645–51.

Rämson R, Jürimäe J, Jürimäe T, Mäestu J. The effect of 4-week training period on plasma neuropeptide Y, leptin and ghrelin responses in male rowers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(5):1873–80.

Chicharrio J, Lopez-Mojares LM, Lucia A, Perez M, Alvarez J, Labanda P, et al. Overtraining parameters in special military units. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1998;69(6):562–8.

Saidi K, Ben Abderrahman A, Boullosa D, Dupont G, Hackney AC, Bideau B, et al. The interplay between plasma hormonal concentrations, physical fitness, workload and mood state changes to periods of congested match play in professional soccer players. Front Physiol. 2020;11:835.

Schumann M, Mykkanen O, Doma K, Mazzolari R, Nyman K, Hakkinen K. Effects of endurance training only versus same-session combined endurance and strength training on physical performance and serum hormone concentrations in recreational endurance runners. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015;40(1):28–36.

Smith C, Myburgh KH. Are the relationships between early activation of lymphocytes and cortisol or testosterone influenced by intensified cycling training in men? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31(3):226–34.

Stenqvist TB, Torstveit MK, Faber J, Melin AK. Impact of a 4-Week intensified endurance training intervention on markers of relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) and performance among well-trained male cyclists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11: 512365.

Sylta O, Tonnessen E, Sandbakk O, Hammarstrom D, Danielsen J, Skovereng K, et al. Effects of high-intensity training on physiological and hormonal adaptions in well-trained cyclists. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(6):1137–46.

Taipale RS, Mikkola J, Nummela A, Vesterinen V, Capostagno B, Walker S, et al. Strength training in endurance runners. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31(7):468–76.

Tanaka H, West KA, Duncan GE, Bassett DR. Changes in plasma tryptophan/branched chain amino acid ratio in responses to training volume variation. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18(4):270–5.

Taipale RS, Mikkola J, Salo T, Hokka L, Vesterinen V, Karemer WJ, et al. Mixed maximal and explosive strength training in recreational endurance runners. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(3):689–99.

Urhausen A, Gabriel HHW, Kindermann W. Impaired pituitary hormonal response to exhaustive exercise in overtrained endurance athletes. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1998;30(3):407–14.

Vervoorn C, Quist AM, Vermulst LJM, Erich WBM, De Vries WR, Thijssen JHH. The behaviour of the plasma free testosterone/cortisol ratio during a season of elite rowing training. Int J Sports Med. 1991;12(3):257–63.

Coutts AJ, Wallace LK, Slattery KM. Monitoring changes in performance, physiology, biochemistry, and psychology during overreaching and recovery in triathletes. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28(2):125–34.

Woods AL, Garvican-Lewis LA, Lundy B, Rice AJ, Thompson KG. New approaches to determine fatigue in elite athletes during intensified training: resting metabolic rate and pacing profile. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):1–18.

Woods AL, Rice AJ, Garvican-Lewis LA, Wallett AM, Lundy B, Rogers MA, et al. The effects of intensified training on resting metabolic rate (RMR), body composition and performance in trained cyclists. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0191644.

Young KC, Kendall KL, Patterson KM, Pandya PD, Fairman CM, Smith SW. Rowing performance, body composition, and bone mineral density outcomes in college-level rowers after a season of concurrent training. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9(6):966–72.

Zaccaria M, Varnier M, Piazza P, Noventa D, Ermolao A. Blunted growth hormone response to maximal exercise in middle-aged versus young subjects and no effect of endurance training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(7):2303–7.

Muscella A, Stefàno E, Marsigliante S. The effects of training on hormonal concentrations and physical performance of football referees. Physiol Rep. 2021;9(8):1–11.

Domaszewska K, Kryściak J, Podgórski T, Nowak A, Ogurkowska MB. The impulse of force as an effective indicator of exercise capacity in competitive rowers and canoeists. J Hum Kinet. 2021;79(1):87–99.

Coutts AJ, Reaburn P, Piva TJ, Rowsell GJ. Monitoring for overreaching in rugby league players. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99(3):313–24.

Coutts A, Reaburn P, Piva TJ, Murphy A. Changes in selected biochemical, muscular strength, power, and endurance measures during deliberate overreaching and tapering in rugby league players. Int J Sports Med. 2006;28(2):116–24.

Dressendorfer RH, Petersen SR, Moss Lovshin SE, Hannon JL, Lee SF, Bell GJ. Performance enhancement with maintenance of resting immune status after intensified cycle training. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12(5):301–7.

Farzad B, Gharakhanlou R, Agha-Alinejad H, Curby DG, Bayati M, Bahraminejad M, et al. Physiological and performance changes from the addition of a sprint interval program to wrestling training. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(9):2392–9.

McCarth SF, Islam H, Hazell TJ. The emerging role of lactate as a mediator of exercise-induced appetite suppression. Am J Physiol Metab. 2020;319(4):E814–9.

Douglas JA, King JA, Clayton DJ, Jackson AP, Sargeant JA, Thackray AE, et al. Acute effects of exercise on appetite, ad libitum energy intake and appetite-regulatory hormones in lean and overweight/obese men and women. Int J Obes. 2017;41(12):1737–44.

Considine RV. Human leptin: an adipocyte hormone with weight-regulatory and endocrine functions. Semin Vasc Med. 2005;5(1):15–24.

Staal S, Sjödin A, Fahrenholtz I, Bonnesen K, Melin AK. Low RMRratio as a surrogate marker for energy deficiency, the choice of predictive equation vital for correctly identifying male and female ballet dancers at risk. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(4):412–8.

Koehler K, Williams NI, Mallinson RJ, Southmayd EA, Allaway HCM, De Souza MJ. Low resting metabolic rate in exercise-associated amenorrhea is not due to a reduced proportion of highly active metabolic tissue compartments. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;311(2):E480–7.

Melin A, Tornberg B, Skouby S, Møller SS, Sundgot-Borgen J, Faber J, et al. Energy availability and the female athlete triad in elite endurance athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2015;25(5):610–22.

Müller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A. Adaptive thermogenesis with weight loss in humans. Obesity. 2013;21(2):218–28.

Cunningham J. Body composition as a determinant of energy expenditure: a synthetic review and a proposed general prediction equation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(6):963–9.

Le Meur Y, Pichon A, Schaal K, Schmitt L, Louis J, Gueneron J, et al. Evidence of parasympathetic hyperactivity in functionally overreached athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(11):2061–71.

Flatt AA, Hornikel B, Esco MR. Heart rate variability and psychometric responses to overload and tapering in collegiate sprint-swimmers. J Sci Med Sport Sports Med. 2017;20(6):606–10.

Coates AM, Incognito AV, Seed JD, Doherty CJ, Millar PJ, Burr JF. Three weeks of overload training increases resting muscle sympathetic activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(5):928–37.

Greenham G, Buckley JD, Garrett J, Eston R, Norton K. Biomarkers of physiological responses to periods of intensified, non-resistance-based exercise training in well-trained male athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sport Med. 2018;48(11):2517–48.

Hackney A. Hypogonadism in exercising males: dysfunction or adaptive-regulatory adjustment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:1–16.

Heikura IA, Uusitalo ALT, Stellingwerff T, Bergland D, Mero AA, Burke LM. Low energy availability is difficult to assess but outcomes have large impact on bone injury rates in elite distance athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(4):403–11.

Drew M, Vlahovich N, Hughes D, Appaneal R, Burke LM, Lundy B, et al. Prevalence of illness, poor mental health and sleep quality and low energy availability prior to the 2016 summer Olympic games. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(1):47–53.

Ihalainen JK, Kettunen OK, McGawley K, Solli G, Mero AA, Kyröläinen H. Body composition, energy availability, training, and menstrual status in female runners. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2021;16(7):1043–8.

O’Connor H, Olds T, Maughan RJ. Physique and performance for track and field events. J Sports Sci. 2007;25(Suppl 1):49–60.

Stellingwerff T. Case study: body composition periodization in an olympic-level female middle-distance runner over a 9-year career. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28(4):428–33.

Bruinvels G, Burden RJ, McGregor AJ, Ackerman KE, Dooley M, Richards T, et al. Sport, exercise and the menstrual cycle: where is the research? Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(6):3–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the production of this review and have read and approved the final manuscript. MK was involved in screening, data extraction and data analysis, and led the writing of this review. AC was involved in screening and contributed to the writing of this review. JB resolved any conflicts in screening and contributed to the writing of this review.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Registration

This review was not registered.

Conflict of interest

Megan Kuikman, Alexandra Coates, and Jamie Burr declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this review.

Availability of data and material

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuikman, M.A., Coates, A.M. & Burr, J.F. Markers of Low Energy Availability in Overreached Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med 52, 2925–2941 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01723-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01723-x