Abstract

Background

Whilst previous meta-analyses have demonstrated that control group responses (CGRs) can negatively influence antidepressant efficacy, no such meta-analysis exists in exercise randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Objective

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating CGRs and predictors in control groups of exercise RCTs among adults with depression.

Methods

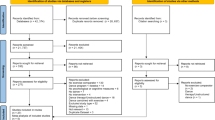

Three authors acquired RCTs from a previous Cochrane review (2013) and conducted updated searches of major databases from January 2013 to August 2015. We included exercise RCTs that (1) involved adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) or depressive symptoms; (2) measured depressive symptoms pre- and post-intervention using a validated measure [e.g. Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)]; and (3) included a non-active control group. A random effects meta-analysis calculating the standardised mean difference (SMD) together with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) was employed to determine CGR.

Results

Across 41 studies, 1122 adults with depression were included [mean (SD) age 50 (18) years, 63 % female]. A large CGR of improved depressive symptoms was evident across all studies (SMD −0.920, 95 % CI −1.11 to −0.729). CGRs were elevated across all subgroup analyses, including high quality studies (n = 11, SMD −1.430, 95 % CI −1.771 to −1.090) and MDD participants (n = 18, SMD −1.248, 95 % CI = −1.585 to −0.911). The CGR equated to an improvement of −7.5 points on the HAM-D (95 % CI −10.30 to −4.89). In MDD participants, increasing age moderated a smaller CGR, while the percentage of drop-outs, baseline depressive symptoms and a longer control group duration moderated a larger CGR (i.e. improvement) (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

In order to demonstrate effectiveness, exercise has to overcome a powerful CGR of approximately double that reported for antidepressant RCTS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015; 386(9995):743–800.

Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):1–12.

Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. The STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):449–59.

Knapen J, Vancampfort D, Moriën Y, et al. Exercise therapy improves both mental and physical health in patients with major depression. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(16):1490–5.

Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Ward PB, et al. Integrating physical activity as medicine in the care of people with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(8):681–2.

Rethorst CD, Wipfli BM, Landers DM. The antidepressive effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2009;39(6):491–511.

Cleare A, Pariante CM, Young AH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(5):459–525.

Vancampfort D, Mitchell AJ, de Hert M, et al. Type 2 diabetes in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of prevalence estimates and predictors. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(10):763–73.

Holt RIG, de Groot M, Lucki I, et al. NIDDK International conference report on diabetes and depression: current understanding and future directions. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2067–77.

Naci H, Ioannidis JPA. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5577.

Dugan SA, Bromberger JT, Eisuke S, et al. Association between physical activity and depressive symptoms: midlife women in SWAN. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(2):335–42.

Schuch FB, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Borowsky C, et al. Exercise and severe major depression: effect on symptom severity and quality of life at discharge in an inpatient cohort. J Psychiatry Res. 2015;61:25–32.

Chalder M, Wiles NJ, Campbell J, et al. Facilitated physical activity as a treatment for depressed adults: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e2758.

Krogh J, Videbech P, Thomsen C, et al. DEMO-II trial. Aerobic exercise versus stretching exercise in patients with major depression-a randomised clinical trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e48316.

Papakostas GI, Østergaard SD, Iovieno N. The nature of placebo response in clinical studies of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(4):456–66.

Schuch FB, Fleck MP. Is exercise an efficacious treatment for depression? A comment upon recent negative findings. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:20.

Rutherford BR, Mori S, Sneed JR, et al. Contribution of spontaneous improvement to placebo response in depression: a meta-analytic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(6):697–702.

Rutherford BR, Roose SP. A model of placebo response in antidepressant clinical trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(7):723–33.

Brunoni AR, Lopes M, Kaptchuk TJ, et al. Placebo response of non-pharmacological and pharmacological trials in major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):1–10.

Lindheimer J, O’Connor P, Dishman R. Quantifying the placebo effect in psychological 5 outcomes of exercise training: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2015;45(5):693–711.

Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane. 2013;9(CD00436):6.

Ekkekakis P. Honey, I shrunk the pooled SMD! Guide to critical appraisal of systematic reviews and meta-analyses using the Cochrane review on exercise for depression as example. Ment Health Phys Act. 2015;8:21–36.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Clin Trials. 2009;6(7):1–6.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders—DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

World Health Organisation. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders – Diagnostic Criteria for Research. 1993.

Hamilton MAX. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–96.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psych. 1961;4:561–71.

Silveira H, Moraes H, Oliveira N, et al. Physical exercise and clinically depressed patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychobiology. 2013;67(2):61–8.

Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Archer T. Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(2):259–72.

Higgins JPT, S G. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed 3 Jan 2015

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–101.

Egger M, Davey SG, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63.

Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psych Bull. 1979;86(3):638–41.

Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Doraiswamy PM, et al. Exercise and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(7):587–96.

Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, O’Connor C, et al. Effects of exercise training on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure: the HF-ACTION randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308(5):465–74.

Bonnet LH. Effects of aerobic exercise in combination with cognitive therapy on self reported depression [dissertation]. Hempstead: Hofstra University; 2005.

Brenes GA, Williamson JD, Messier SP, et al. Treatment of minor depression in older adults: a pilot study comparing sertraline and exercise. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(1):61–8.

Chu I-H, Buckworth J, Kirby TE, et al. Effect of exercise intensity on depressive symptoms in women. Ment Health Phy Act. 2009;2(1):37–43.

Doyne EJ, Ossip-Klein DJ, Bowman ED, et al. Running versus weight lifting in the treatment of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(5):748.

Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, et al. Exercise treatment for depression: efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(1):1–8.

Epstein D. Aerobic activity versus group cognitive therapy: an evaluative study of contrasting interventions for the alleviation of clinical depression. Reno: University of Nevada; 1986.

Foley LS, Prapavessis H, Osuch EA, et al. An examination of potential mechanisms for exercise as a treatment for depression: a pilot study. Ment Health Phys Act. 2008;1(2):69–73.

Fremont J, Craighead LW. Aerobic exercise and cognitive therapy in the treatment of dysphoric moods. Cogn Ther Res. 1987;11(2):241–51.

Gary RA, Dunbar SB, Higgins MK, et al. Combined exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy improves outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(2):119–31.

Hemat-Far A, Shahsavari A, Roholla Mousavi S. Effects of selected aerobic exercises on the depression and concentrations of plasma serotonin in the depressed female students aged 18 to 25. J Appl Res Clin Exp Ther. 2012;12(1):47.

Hess-Homeier MJ. A comparison of Beck’s cognitive therapy and jogging as treatments for depression. Missoula: University of Montana; 1981.

Hoffman JM, Bell KR, Powell JM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of exercise to improve mood after traumatic brain injury. PM R. 2010;2(10):911–9.

Klein MH, Greist JH, Gurman AS, et al. A comparative outcome study of group psychotherapy vs. exercise treatments for depression. Int J Ment Health. 1984:148–76.

Knubben K, Reischies FM, Adli M, et al. A randomised, controlled study on the effects of a short-term endurance training programme in patients with major depression. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(1):29–33.

Krogh J, Saltin B, Gluud C, et al. The DEMO trial: a randomized, parallel-group, observer-blinded clinical trial of strength versus aerobic versus relaxation training for patients with mild to moderate depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(6):790–800.

Mather AS, Rodriguez C, Guthrie MF, et al. Effects of exercise on depressive symptoms in older adults with poorly responsive depressive disorder Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180(5):411–5.

McNeil JK, LeBlanc EM, Joyner M. The effect of exercise on depressive symptoms in the moderately depressed elderly. Psychol Aging. 1991;6(3):487.

Mota-Pereira J, Silverio J, Carvalho S, et al. Moderate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1005–11.

Mutrie N. Exercise as a treatment for depression within a national health service. Eugene: Microform Publications, College of Human Development and Performance, University of Oregon; 1989.

Nabkasorn C, Miyai N, Sootmongkol A, et al. Effects of physical exercise on depression, neuroendocrine stress hormones and physiological fitness in adolescent females with depressive symptoms. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(2):179–84.

Orth DK. Clinical Treatments for Depression. Morgantown: West Virginia University; 1979.

Setaro JL. Aerobic exercise and group counseling in the treatment of anxiety and depression. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International/UMI; 1985.

Shahidi M, Mojtahed A, Modabbernia A, et al. Laughter yoga versus group exercise program in elderly depressed women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):322–7.

Sims J, Galea M, Taylor N, et al. Regenerate: assessing the feasibility of a strength-training program to enhance the physical and mental health of chronic post stroke patients with depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(1):76–83.

Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(6):768–76.

Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52(1):M27–35.

Veale D, Le Fevre K, Pantelis C, et al. Aerobic exercise in the adjunctive treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial. J R Soc Med. 1992;85(9):541–4.

Williams C, Tappen R. Exercise training for depressed older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(1):72–80.

Danielsson L, Papoulias I, Petersson EL, et al. Exercise or basic body awareness therapy as add-on treatment for major depression: a controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:98–106.

Kerling A, Tegtbur U, Gützlaff E, et al. Effects of adjunctive exercise on physiological and psychological parameters in depression: a randomized pilot trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;177:1–6.

Martiny K, Refsgaard E, Lund V, et al. A 9-week randomized trial comparing a chronotherapeutic intervention (wake and light therapy) to exercise in major depressive disorder patients treated with duloxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(9):1234.

Verrusio W, Andreozzi P, Marigliano B, et al. Exercise training and music therapy in elderly with depressive syndrome: a pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(4):614–20.

Huang T-T, Liu C-B, Tsai Y-H, et al. Physical fitness exercise versus cognitive behavior therapy on reducing the depressive symptoms among community-dwelling elderly adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(10):1542–52.

Salehi I, Hosseini SM, Haghighi M, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy and aerobic exercise training increased BDNF and ameliorated depressive symptoms in patients suffering from treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;57:117–24.

Hallgren M, Kraepelien M, Öjehagen A, et al. Physical exercise and internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2015. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160101

Belvederi Murri M, Amore M, Menchetti M, et al. Physical exercise for late-life major depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(3):235–42.

Pilu A, Sorba M, Hardoy MC, et al. Efficacy of physical activity in the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorders: preliminary results. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:8.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression: management of depression in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London; 2004.

Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1435–45.

Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(1):1–2.

Bridge JA, Birmaher B, Iyengar S, et al. Placebo response in randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for pediatric major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(1):42–9.

Stetler C. Adherence, expectations and the placebo response: Why is good adherence to an inert treatment beneficial? Psychol Health. 2014;29(2):127–40.

Benedetti F. Placebo effects: understanding the mechanisms in health and disease. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Ojanen M. Can the true effects of exercise on psychological variables be separated from placebo effects?/Les effets veritables de l’exercice physique sur les variables psychologiques peuvent-ils etre separes des effets placebo ? Int J Sport Psychol. 1994;25(1):63–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Davy Vancampfort has support from the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen). Brendon Stubbs was supported by the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London theme for this article. No other sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Conflicts of interest

Brendon Stubbs, Davy Vancampfort, Simon Rosenbaum, Philip Ward, Justin Richards, Michael Ussher and Felipe Schuch declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this review.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required to conduct this review.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Rosenbaum, S. et al. Challenges Establishing the Efficacy of Exercise as an Antidepressant Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Control Group Responses in Exercise Randomised Controlled Trials. Sports Med 46, 699–713 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0441-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0441-5