Abstract

Objective

To examine the prevalence of exposure and perinatal outcomes associated with in utero exposure to methoxyflurane.

Design, Setting and Population

Whole-population ambulance data in Western Australia (WA) were linked to the statutory perinatal data collection to identify pregnant women transferred by ambulance between 2000 and 2016. The proportion of neonates in WA exposed to methoxyflurane, fentanyl or no analgesia during an ambulance transfer was calculated. Perinatal outcomes of pregnancies exposed to methoxyflurane (n=1579) were compared to those exposed to fentanyl (n=203) or no analgesia (n=10524) using multivariable logistic regression modelling. Perinatal outcomes were considered overall and by trimester of exposure.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes were the prevalence of in utero methoxyflurane exposure and Apgar score on the day of delivery.

Results

In the study period, 0.4% of all neonates born in WA were exposed to methoxyflurane in utero. Methoxyflurane exposure on the day of delivery (n=657) was not associated with an increased likelihood of a low Apgar score at five minutes compared with no analgesia (n=2667) (OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.91-1.67). Whereas fentanyl exposure (n=22) was associated with an increased likelihood of low Apgar score compared with methoxyflurane (OR 3.67, 95% CI 1.18-11.48).

Conclusions

Methoxyflurane is commonly used by ambulance services to treat pain in pregnant women in WA. While not recommended for use in pregnancy, pregnancies exposed to methoxyflurane did not have an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

One in 250 neonates born in WA during this study were exposed to methoxyflurane in utero. |

Although there was no observed increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, the safety of methoxyflurane cannot be assumed based on this study alone. |

1 Introduction

Widely used in the 1960s as an anaesthetic, methoxyflurane was withdrawn from use in most countries in the 1970s following identification of dose-dependent nephrotoxicity (starting from 40 to 60 mL) [1]. However, its use continued in Australia, where it was repurposed at low doses (up to 6 mL) as an analgesic agent [2]. In Australia, methoxyflurane remains the most commonly administered analgesia by paramedics due to its ease of use, rapid onset of action and efficacy [3,4,5]. Given its routine use, there is potential for frequent exposure during pregnancy. In a cohort study of pregnant women utilising the New South Wales ambulance service, one-third of pregnant women required prehospital emergency analgesia, with methoxyflurane administered to 79.9% of these women [6].

Despite its widespread use, there is limited evidence to inform on the safety and teratogenicity of methoxyflurane during pregnancy, particularly at the lower dose used for analgesia. Methoxyflurane displays relatively unrestricted transfer across the placenta [7, 8]. Studies from the 1960s report neonatal respiratory depression following methoxyflurane anaesthesia in mothers on the day of delivery [7,8,9,10]; however, this was not observed when used at analgesic doses [11,12,13]. In vitro, methoxyflurane has been observed to significantly depress uterine muscle contraction from analgesic equivalent concentrations [14]. In animals, methoxyflurane is observed to reduce uterine circulation in a dose-dependent manner [15] and to reduce birth weight following exposure to subanaesthetic concentrations throughout the entirety of gestation [16]. One Swedish case-control study reported a 2.4-fold increase in the odds of nephroblastoma in children following in utero exposure, however the authors concluded this may be a spurious observation [17]. There are no other reports in the literature implicating methoxyflurane as a potential teratogen.

In Australia, methoxyflurane is classified as a pregnancy category C drug, i.e. a drug that has caused or may be suspected of causing harmful effects on the foetus or neonate without causing malformation [18]. Consequently, it is not recommended for use in pregnancy [18]. Given the potential for exposure in pregnancy in an emergency setting, further investigation is warranted. The aim of this study was therefore to examine the prevalence of exposure and perinatal outcomes following in utero exposure to methoxyflurane using a large retrospective cohort.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This multiple comparison group retrospective cohort study used linked health data to examine the prevalence of exposure and perinatal outcomes following in utero exposure to methoxyflurane over a 17-year period.

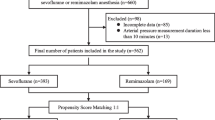

2.2 Study Setting and Participants

All neonates born to women transported by ambulance during pregnancy in Western Australia (WA) between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2016 were considered for inclusion (n = 15,967). Pregnancies exposed to methoxyflurane were compared with pregnancies that received either fentanyl or no analgesia during their transfer to hospital. Fentanyl was used as a comparator as it was the second most common analgesic agent administered in the study cohort following methoxyflurane in ambulance settings. Doses of methoxyflurane and fentanyl administered were not available. Women exposed to an alternative analgesia (paracetamol, ketamine, morphine, lignocaine and cophenylcaine) were excluded, although the use of these medications was rare (< 1% combined). Women with a multiple pregnancy (n = 1194), women < 16 or > 45 years of age (n = 94), subsequent pregnancies (n = 2205), and pregnancies exposed to both methoxyflurane and fentanyl (n = 56) were excluded when examining perinatal outcomes.

2.3 Outcomes

Overall prevalence of exposure was determined as the number of neonates born during the study period exposed to each treatment group as a proportion of the total number of neonates born in WA during the study period (retrieved from the Australian Bureau of Statistics) [19].

Outcomes were considered by trimester of exposure based on biologically plausible outcomes for that trimester. Day of delivery was considered as a separate exposure time point given delivery was not limited to trimester three. Perinatal outcomes were considered from the estimated date of conception up to 4 weeks following birth, except for congenital anomalies, which may be diagnosed up to 6 years of age in WA.

The primary outcomes were the overall prevalence of in utero methoxyflurane exposure and an Apgar score <7 at 5 min if exposed on the day of delivery. The secondary outcome considered for trimester one was all-cause congenital anomalies. Congenital anomalies were defined using the British Paediatric Association extension of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [20]. Secondary outcomes for trimesters two and three were mean gestation at birth, mean birth weight, neonatal length of hospital stay, admission to a special care nursery, and perinatal mortality. Admission to a special care nursery was defined as a level two or three nursery, and perinatal mortality was defined as death between 20 weeks’ gestation to 28 days following birth. Secondary outcomes for the day of delivery were foetal distress, neonatal length of hospital stay, admission to a special care nursery, and perinatal mortality.

2.4 Data Sources and Measurements

Participants were identified through St John Ambulance WA records, which is the only emergency ambulance service in WA. These patients were linked to the WA Midwives Notification System to identify women who were pregnant at the time of ambulance transfer, as well as their pregnancy outcomes. The period of pregnancy was calculated by subtracting the estimated gestation at delivery from the date of delivery and adding 14 days. The pregnancies were also linked to the WA Register of Developmental Anomalies and the WA Mortality Registry to identify congenital anomalies and mortality. Statutory reporting requirements in WA to these registries provided complete coverage of the population, and all data were available up to 31 December 2016. All data extraction and linkage were carried out by the WA Data Linkage Branch and a description of the linkage process has been previously published [21].

2.5 Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were performed for all variables. Prevalence was measured as live and stillborn neonates who were transported by ambulance while in utero proportional to the number of neonates born in WA each year (retrieved from the Australian Bureau of Statistics) [19]. Multivariable linear regression modelling was used to examine the relationship between treatment exposure and birth weight and gestational age, and negative binomial regression modelling was used to examine the relationship between treatment exposure and neonatal length of hospital stay. Multivariable logistic regression modelling was used to examine the relationship between treatment exposure and the remaining perinatal outcomes, as described above, in separate models. Models were adjusted to account for maternal age, smoking status during pregnancy, and Aboriginal status. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was used to confer significance. Data were analysed in Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

2.6 Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of WA Human Research Ethics Committee (RA/4/20/4788) and the WA Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee (RGS 0000001175). Approval for the relevant data was sought from the WA Data Linkage Branch (201711.01_001) and the relevant custodians. All data were de-identified and outcomes with fewer than five observations were not reported in order to maintain anonymity.

3 Results

3.1 Treatment Exposure

Between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2016, 505,982 neonates were born in WA. Of these, 15,967 neonates (3.2%) were transferred by ambulance in utero, with 1822 neonates (0.4%) exposed to methoxyflurane. Of those transferred by ambulance in utero, 11.4% (n = 1822) were exposed to methoxyflurane and 1.7% (n = 275) were exposed to fentanyl. Exposure to methoxyflurane most frequently occurred on the day of delivery (n = 754, 41.4%), followed by trimester three (n = 447, 24.5%).

3.2 Participants

During the study period, 12,306 pregnancies met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Women exposed to methoxyflurane were, on average, almost 1 year younger (27.3 vs. 28.2 years), more likely to smoke during pregnancy (36.3% vs. 25.7%) and identified as Aboriginal Australian (22.1% vs. 13.6%) compared with those not receiving any analgesia. Pregnancy characteristics of women treated with methoxyflurane were not significantly different to those treated with fentanyl, except women exposed to fentanyl were more likely from areas of higher social disadvantage (21.7% vs. 13.1%) and more likely to reside in major Australian cities (79.3% vs. 69.9%).

3.3 Trimester One

Of the pregnancies exposed to methoxyflurane, 270 pregnancies (14.8%) were exposed during the first trimester, while first-trimester fentanyl exposure occurred in 75 pregnancies (27.2%). First-trimester methoxyflurane exposure was not associated with a significant increase in the odds of all-cause congenital anomalies compared with either fentanyl or no analgesia exposed neonates (Table 2). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the odds of threatened abortion or perinatal mortality between exposure groups during trimester one.

3.4 Trimester Two

Exposure in trimester two occurred in 321 neonates (17.6%) exposed to methoxyflurane and 77 neonates (28.0%) exposed to fentanyl. There were no differences in pregnancy outcomes between those exposed to either methoxyflurane or fentanyl in trimester two (Table 3). Neonates of pregnancies exposed to methoxyflurane in trimester two were, on average, 1-week older gestation (incidence rate ratio [IRR] −0.90, 95% confidence interval [CI] −1.53 to −0.28), weighed 189 g more at birth (IRR −202.8, 95% CI −325.1 to −80.6) and stayed for 1 less day in hospital (regression coefficient 1.65, 95% CI 1.40–1.94) than those not exposed to analgesia.

3.5 Trimester Three

Exposure in trimester three occurred in 403 neonates (22.1%) exposed to methoxyflurane in utero and 33 neonates (12.0%) exposed to fentanyl in utero. There were no differences in pregnancy outcomes between those exposed to methoxyflurane or fentanyl in trimester three (Table 4). Neonates of pregnancies exposed in trimester three to methoxyflurane were, on average, 1-week older gestation (IRR − 0.94, 95% CI − 1.23 to − 0.65), weighed 204 g more at birth (IRR − 223, 95% CI − 297.7 to − 149.5) and stayed for 1 less day in hospital (regression coefficient 1.36, 95% CI 1.22–1.51) compared with those not exposed to analgesia during the same period.

3.6 Day of Delivery

Exposure on the day of delivery occurred in 657 neonates (36.1%) exposed to methoxyflurane and 22 neonates (8.0%) exposed to fentanyl. A low Apgar score and perinatal mortality occurred in less than five neonates exposed to fentanyl but occurred at higher rates in neonates exposed in utero to fentanyl compared to methoxyflurane (Table 5). There were no other differences observed in pregnancy outcomes between those exposed to methoxyflurane or fentanyl on day of delivery. Pregnancies administered no analgesia on the day of delivery had higher odds of experiencing foetal distress (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.93–1.43) or requiring neonatal resuscitation (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.97–1.33) compared with those administered methoxyflurane during ambulance transfer. Perinatal mortality occurred at almost twice the rate in pregnancies administered no analgesia (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.13–3.36) and had an almost 10% higher rate of admission to the special care unit (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.06–1.45) compared with those exposed to methoxyflurane in utero.

4 Discussion

4.1 Main Findings

Methoxyflurane was administered to 11.4% of pregnant women transported by ambulance in WA between 2000 and 2016, representing the most common analgesic used by pregnant women in such settings. This equated to 0.4% of all births in WA being exposed to methoxyflurane during this period. Unsurprisingly, the most common exposure times were the third trimester and the day of delivery, suggesting that while methoxyflurane is not recommended for use in pregnancy (due to its category C status), its use is not avoided, especially at or near the time of delivery. In contrast, the use of fentanyl, also a category C medication, was more likely to be used in the first and second trimesters of pregnancy in ambulance settings, likely due to concerns regarding the potential for fentanyl to cause neonatal respiratory depression following birth [18].

Outcomes in neonates who were exposed to methoxyflurane in utero were generally similar or superior to neonates exposed to fentanyl or no analgesia. An important finding of the study was the absence of an increased risk of congenital anomalies in pregnancies exposed to real-world use of methoxyflurane in the first trimester. This is consistent with the absence of literature implicating methoxyflurane as a teratogen, including in animal models, where structural abnormalities were not associated with longer duration and higher dosage of methoxyflurane use [16]. Similarly, there was no evidence that methoxyflurane exposure during trimesters two and three is associated with poor foetal growth, shortened gestation period, or perinatal mortality. However, an animal model observed a reduction in average foetal birth weight following exposure to higher subanaesthetic concentrations of methoxyflurane [16], but this may be attributable to the longer duration and higher dose of methoxyflurane exposure that occurred within this animal model [16]. Methoxyflurane use on the day of delivery was not associated with an increased risk of perinatal mortality, foetal distress, resuscitation required following birth, or Apgar score <7 at 5 min. This supports the literature from the 1970s, which reports no association with neonatal respiratory depression following methoxyflurane analgesia use in labour [11, 13].

Women administered methoxyflurane on the day of delivery were more likely to be Aboriginal, of younger age, and smoke during pregnancy, but did not appear to have more adverse pregnancy outcomes. It is possible that these women were less likely to have suitable transport or support upon going into labour and thus required the assistance of an ambulance. The overall study cohort also had a relatively high prevalence of characteristics that are overrepresented in vulnerable populations. Compared with the general WA population, women receiving ambulance services were more likely to be Aboriginal, smoke during pregnancy, have never been married, and be from an area of high socioeconomic disadvantage. For example, Aboriginal women made up an estimated 4.2% of the female population aged 15–44 years in WA in 2016, whereas in this study, Aboriginal women comprised 18.7% of the pregnant women receiving ambulance services. Similarly, 29.8% of women transported by ambulance smoked during pregnancy, compared with 15.4% of mothers in WA in 2008 (around the mid-point of the study observation period). Hence, the outcomes of women transported by ambulance during pregnancy, including those administered methoxyflurane, are likely poorer than those seen in the general population.

4.2 Strengths and Limitations

This study captured all women transported by ambulance and exposed to methoxyflurane in WA over a 17-year period, allowing for the investigation of outcomes by trimester and of uncommon events with sufficient statistical power. Due to mandatory reporting to WA health registries and St John Ambulance being the only emergency ambulance service in WA, this study captures all the data for the subpopulation of pregnant women exposed to methoxyflurane in a real-world setting.

However, several limitations existed. Due to the lack of randomisation in analgesia administration, confounding by indication limits the ability to compare the inherently different exposure cohorts. The effect of this is demonstrated where mothers who received no analgesia during their transfer had earlier gestations at birth, lower birthweight babies, longer neonatal length of hospital stay and more frequent admissions to the special care nursery when compared with pregnancies exposed to methoxyflurane. It is likely that paramedics did not administer analgesia to pregnancies with known pre-existing risk factors for adverse outcomes, where appropriate. Exposure to fentanyl was included in this study as a control exposure to minimise such effects. However, comparison of the pregnancy and birth outcomes between the cohorts should be made with caution and methoxyflurane exposure should not be viewed as having a protective effect on pregnancy.

The study did not capture pregnancies that resulted in spontaneous or medical abortions prior to 20 weeks of gestation. Therefore, this study likely underestimates first trimester exposure to methoxyflurane, and it is unclear what the impact methoxyflurane may have on pregnancy loss prior to 20 weeks of gestation. Additionally, as the study did not examine frequency of exposure and due to the absence of data on methoxyflurane dose administered during each transfer, this limits the study’s ability to comment on a dose–response relationship or the teratogenicity of methoxyflurane. Furthermore, this study did not examine other types of foetal damage beyond malformation, including long-term neurodevelopment.

Despite the long collection period and state-wide ascertainment of data, the sample size did not provide sufficient power for several outcomes, including perinatal mortality or type-specific congenital anomalies. Future research is warranted to investigate these rare events using multi-jurisdictional datasets. Despite these limitations, the study has value in providing novel information on methoxyflurane exposure in pregnancy utilising a unique dataset.

5 Conclusion

Although methoxyflurane is not recommended for use in pregnancy, it appears that administration still frequently occurs, with 0.4% of all neonates born in WA during the study period being exposed in utero to methoxyflurane. Although pregnancies exposed to methoxyflurane were not observed to have increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes, the safety of methoxyflurane cannot be assumed based on this study alone.

References

Mazze RI. Methoxyflurane revisited: tale of an anesthetic from cradle to grave. Anesthesiol J Am Soc Anesthesiol. 2006;105(4):843–6.

Dayan A. Analgesic use of inhaled methoxyflurane: evaluation of its potential nephrotoxicity. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2016;35(1):91–100.

Porter KM, Dayan AD, Dickerson S, Middleton PM. The role of inhaled methoxyflurane in acute pain management. Open Access Emerg Med. 2018;10:149.

Bendall JC, Simpson PM, Middleton PM. Prehospital analgesia in New South Wales, Australia. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(6):422–6.

Coffey F, Dissmann P, Mirza K, Lomax M. Methoxyflurane analgesia in adult patients in the emergency department: a subgroup analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (STOP!). Adv Ther. 2016;33(11):2012–31.

McLelland G, McKenna L, Morgans A, Smith K. Antenatal emergency care provided by paramedics: a one-year clinical profile. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2016;20(4):531–8.

Clark R, Cooper J, Brown W, Greifenstein F. The effect of methoxyflurane on the foetus. Br J Anaesth. 1970;42(4):286–94.

Siker E, Wolfson B, Duenansky J, Fitting JRG. Placental transfer of methoxyflurane. Br J Anaesth. 1968;40(8):588–92.

Cosmi E, Marx G. Acid-base status and clinical condition of mother and foetus following methoxyflurane anaesthesia for vaginal delivery. Br J Anaesth. 1968;40(2):94–8.

Boisvert M, Hudon F. Clinical evaluation of methoxvflurane in obstetrical anaesthesia: a report on 500 cases. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1962;9(4):325.

Rosen M, Mushin W, Jones P, Jones E. Field trial of methoxyflurane, nitrous oxide, and trichloroethylene as obstetric analgesics. Br Med J. 1969;3(5665):263–7.

Clark RB, Beard AG, Thompson DS, Barclay DL. Maternal and neonatal plasma inorganic fluoride levels after methoxyflurane analgesia for labor and delivery. Anesthesiology. 1976;45(1):88–91.

Palahniuk RJ, Scatliff J, Biehl D, Wiebe H, Sankaran K. Maternal and neonatal effects of methoxyflurane, nitrous oxide and lumbar epidural anaesthesia for caesarean section. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1977;24(5):586–96.

Paull J, Ziccone S. Halothane, enflurane, methoxyflurane, and isolated human uterine muscle. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1980;8(4):397–401.

Smith JB, Manning F, Palahniuk R. Maternal and foetal effects of methoxyflurane anaesthesia in the pregnant ewe. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1975;22(4):449–59.

Pope W, Halsey M, Lansdown A, Simmonds A, Bateman P. Fetotoxicity in rats following chronic exposure to halothane, nitrous oxide, or methoxyflurane. Anesthesiology. 1978;48(1):11–6.

Lindblad P, Zack M, Adami HO, Ericson A. Maternal and perinatal risk factors for Wilms’ tumor: a nationwide nested case-control study in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 1992;51(1):38–41.

MIMS. Crows Nest (NSW): MIMS Australia Pty Ltd; 2019 [cited 3 Mar 2020]. https://www.mimsonline.com.au

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Births, by year and month of occurrence, by state Canberra; 2020 [cited 3 Mar 2020]. http://stat.data.abs.gov.au/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=BIRTHS_MONTH_OCCURRENCE.

Western Australian Register of Developmental Anomalies. BPA-ICD9 Diagnosis Code Listing; 2013. Perth (WA) [cited 3 Mar 2020]. https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Files/Corporate/generaldocuments/WARDA/PDF/warda_bdr_diagcodes_by_code.pdf.

Sprivulis P, Silva JAD, Jacobs I, Jelinek G, Swift R. ECHO: the Western Australian emergency care hospitalisation and outcome linked data project. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30(2):123–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Linkage, Data Outputs and Research Data Services Teams at the Western Australian Data Linkage Branch, as well as St John Ambulance, the Midwives Notification Scheme, Western Australian Register of Developmental Anomalies, the Western Australian Hospital Morbidity Data Collection, and the Western Australian Mortality Register for their contribution.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP and EK designed the study and analysed the data. FS, KM and DP contributed to the design and implementation of the research. EK performed the statistical analysis. AP wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. EK and DP supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research is a subcomponent of a larger study funded by Mundipharma International Limited to provide real-world data on the safety of methoxyflurane. Mundipharma had no influence over the study design, data analysis or report writing.

Conflicts of interest

Anwyn Pyle, Erin Kelty, Frank Sanfilippo, Kevin Murray and David Preen declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of WA Human Research Ethics Committee (RA/4/20/4788) and the WA Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee (RGS 0000001175). Approval for the relevant data was sought from the WA Data Linkage Branch (201711.01_001) and the relevant custodians. All data were de-identified and outcomes with fewer than five observations were not reported in order to maintain anonymity.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Data availability

The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise research participant privacy due to the rare nature of some event occurrences.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pyle, A., Kelty, E., Sanfilippo, F. et al. Prevalence and Perinatal Outcomes Following In Utero Exposure to Prehospital Emergency Methoxyflurane: A 17-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. Pediatr Drugs 24, 547–554 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-022-00519-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-022-00519-w