Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often used for pediatric pain management in the emergency setting and postoperatively. This narrative literature review evaluates pain relief, opioid requirements, and adverse effects associated with NSAID use. A PubMed search was conducted to identify randomized controlled trials evaluating the use of conventional systemic NSAIDs as pain management for children in the perioperative or emergency department (traumatic injury) setting. Trials of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (“coxibs”) were excluded. Search results included studies of ibuprofen (n = 12), ketoprofen (n = 5), ketorolac (n = 6), and diclofenac (n = 4). NSAIDs reduced the opioid requirement in 10 of 13 studies in which this outcome was measured. NSAID use did not compromise pain relief; NSAIDs provided improved or similar pain scores compared with opioids (or other control) in 24 of 27 studies. Adverse event frequencies were reported in 26 studies; adverse event frequencies with NSAIDs were lower than with opioids (or other control) in three of 26 studies, similar in 21 of 26 studies, and more frequent in two of 26 studies. Perioperative and emergency department use of NSAIDs may reduce opioid requirements while maintaining pain control, with similar or reduced frequencies of opioid-associated adverse events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the last several years, opioid analgesics have fallen out of favor for use in the pediatric population for postsurgical pain, and other options are being sought. |

Based on a PubMed literature search, the utility of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the treatment of pain associated with surgical procedures or traumatic injury in the pediatric population was evaluated. |

The results of 27 articles detailing studies on conventional NSAIDs (ibuprofen, ketorolac, ketoprofen, and diclofenac) administered systemically in this setting indicate that NSAIDs were able to reduce total opioid requirements without compromise of pain control and were associated with similar or fewer adverse events versus traditional opioid therapy. |

1 Introduction

Pain associated with surgical procedures or traumatic injury is commonly reported in the pediatric population, with increasing evidence suggesting that pain in children is managed inadequately [1, 2]. This is attributed, in part, to concerns surrounding the side effects of opioids [3, 4]. Acute exposure to opioids can lead to a variety of adverse events (AEs), including nausea, vomiting, pruritus, constipation, and respiratory depression [5], and may increase the odds of developing chronic opioid use and opioid use disorder, an important class-specific risk associated with these medications [6,7,8]. In one study, approximately one-fourth of children experienced an AE related to postoperative opioid use that required intervention, opioid reversal, or escalation in care [9].

Mild-to-moderate pediatric pain is often managed with nonopioid options, such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen. However, evidence indicates that these products may be underdosed in emergency settings. In a recent survey of 17 Italian centers, including 4 pediatric and 13 general hospitals, it was noted that 61% of 1471 cases reviewed involved insufficient dosing with these agents. Underdosing was associated with the use of rectal acetaminophen, weight < 12 or > 40 kg, and the use of oral ibuprofen [10]. Additionally, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have become commonly used as part of a multimodal pain management strategy in pediatric patients with acute pain and offer several potential advantages [11,12,13,14,15]. NSAIDs reduce pain and inflammation by inhibiting prostaglandin production by cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes [16]. Because this mechanism of action is distinct from that of opioids, NSAIDs have the potential to produce adequate levels of pain relief while reducing overall opioid requirements and associated AEs [17]. However, NSAIDs are associated with their own potential AEs, including gastropathy, renal impairment, potential to prolong bleeding via platelet inhibition [16], and possible increased risk of severe infection [18] or acceleration of an infectious disease course [19]. As such, it is important to characterize the evidence for benefits and risks associated with NSAID use in order to determine their clinical utility as part of the pain management strategy for pediatric patients. This narrative review provides an overview of recently published data concerning the use of NSAIDs in pediatric patients with acute pain due to surgery or injury.

2 Literature Search

The published medical literature was searched using the PubMed search engine. Clinical trials that evaluated the use of systemically administered conventional NSAIDs as part of a perioperative or emergency department traumatic pain management strategy in pediatric patients were assessed. Keywords were used to construct the search string: “opioid AND (postoperative OR emergency OR tonsillectomy OR fracture OR musculoskeletal) AND (NSAID OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac OR ibuprofen OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR ketorolac OR lornoxicam OR meloxicam OR naproxen OR oxaprozin OR piroxicam).” Searches were limited to randomized clinical trials in the pediatric population published in English from 1 January 2000 through 2 December 2020. Outcomes of interest included opioid consumption, pain control, and AE incidences. Studies reporting nonsystemic use of conventional NSAIDs were excluded, as were studies focused only on COX-2–specific inhibitors (coxibs).

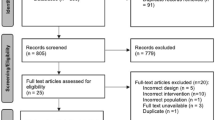

In total, 27 publications met the inclusion criteria outlined and are included in this review. The NSAIDs evaluated in our pool of studies are shown in Fig. 1. Ibuprofen was the agent most frequently evaluated (12 studies); NSAID study data were also obtained for ketorolac (six), ketoprofen (five), and diclofenac (four). Across the 27 studies identified, reports of AEs were noted in 26 studies and effects on pain scores were reported in 24 studies. Opioid-sparing effect details were reported in only 13 studies. An overview of the published literature by NSAID is provided.

3 Ibuprofen

Ibuprofen is the most widely studied and used NSAID in children for the management of acute pain [20, 21] and is the only NSAID approved for use in children as young as 6 months [22]. A total of 12 studies evaluating ibuprofen in children were reviewed; results from these studies are summarized in Table 1. More than half (7/12) of the ibuprofen studies included patients with trauma, fractures, and other musculoskeletal injuries [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Four studies were conducted in children after undergoing tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy [30,31,32,33], and the final study enrolled patients who underwent minor outpatient surgery at an orthopedic clinic [34]. Ibuprofen was used at a dose of 10 mg/kg in 10 of the 12 trials reviewed [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 34], whereas the Pickering et al. [32] study used ibuprofen at a dose of 5 mg/kg and Viitanen et al. [33] used a 15-mg/kg dose administered rectally as a suppository. The comparator groups in these trials varied and included both placebo-treated and opioid-treated patients. Additionally, several studies evaluated ibuprofen as a single medication versus combined with an opioid analgesic [26,27,28].

Opioid-sparing effects were assessed and reported in three of 12 studies, two of which found that the use of ibuprofen reduced opioid requirements. In the first positive study, children received meperidine in 5-mg doses as rescue analgesia following adenoidectomy if pain scores exceeded a preset threshold. Following anesthetic induction, the use of single-dose ibuprofen 15 mg/kg was associated with a 27% reduction in meperidine rescue use compared with placebo (p = 0.001) in the postoperative period [33]. In the second positive study, a single preoperative dose of ibuprofen 10 mg/kg intravenously was associated with significantly fewer doses (p = 0.021) and amounts (p = 0.037) of rescue fentanyl compared with those who did not receive preoperative ibuprofen [31]. In the remaining study, children undergoing tonsillectomy were premedicated with acetaminophen 20 mg/kg combined with either placebo, ibuprofen 5 mg/kg, or rofecoxib 0.625 mg/kg, and the use of supplemental analgesia required (i.e., ibuprofen 5 mg/kg or codeine 1 mg/kg) over the first 2 h and over 24 h postoperatively was assessed. While premedication with ibuprofen was associated with significantly fewer children requiring early (within 2 h of surgery) rescue analgesia versus placebo or rofecoxib (43 vs. 72 vs. 68%, respectively; p = 0.03), the overall opioid requirement was no different between groups over the first 24 h [32].

Of the 12 ibuprofen studies reviewed, 11 provided assessment of pain scores; a majority of these (n = 9) found no significant differences between groups [24,25,26,27, 29,30,31,32, 34]. In two studies conducted in children treated for musculoskeletal trauma, ibuprofen 10 mg/kg was associated with significantly improved pain scores versus acetaminophen 15 mg/kg or codeine 1 mg/kg (p ≤ 0.004 for both) in one study [23] and versus morphine 0.2 mg/kg (p = 0.02) in the other [28].

All of the studies involving ibuprofen reported on AEs and other aspects of safety and tolerability; seven of 12 studies reported there were no significant differences in AEs or class effects between opioids and ibuprofen [23, 25, 27, 30,31,32,33]. However, in children with orthopedic injuries, Koller et al. [26] noted significantly more AEs in patients treated with a combination of ibuprofen and oxycodone compared with those treated with either medication alone (p = 0.036). In children with arm fracture pain, Drendel et al. [24] found the combination of acetaminophen and codeine was associated with significantly higher rates of nausea and vomiting (18 and 11%, respectively) than ibuprofen alone (5.0 and 2.4%, respectively). The remaining three studies all found significantly more AEs associated with morphine than ibuprofen in children who had musculoskeletal injuries or who were undergoing orthopedic surgery [28, 29, 34]. Nausea [29, 34], vomiting [29, 34], drowsiness [29, 34], and dizziness [34] were reported significantly more often among patients treated with morphine versus those treated with ibuprofen.

4 Ketorolac

Ketorolac was the first NSAID approved in the USA for intravenous postoperative pain in adults, and although not approved for use in children in the USA, UK, or Europe, it has been studied in the pediatric population [35]. In total, we identified six studies examining the use of ketorolac in pediatric patients; details of the included studies are provided in Table 2. All studies involved intravenous administration of ketorolac in a perioperative setting [36,37,38,39,40], except the study by Neri et al. [41], which used sublingual ketorolac and tramadol in an emergency department. The trials compared ketorolac with a variety of opioid analgesics, including morphine, fentanyl, tramadol, and meperidine.

Opioid-sparing outcomes were reported in three of six studies; of the three studies, two found significant reductions in opioid consumption associated with the use of ketorolac. Carney et al. [36] found that adding ketorolac 0.5 mg/kg to a standard regimen of morphine after inpatient surgery significantly reduced the morphine requirement for pain control on postoperative days 0 and 1 (p < 0.05), whereas Jo et al. [37] found that children treated with ketorolac postoperatively required 69% less tramadol rescue medication in the first 24 h after surgery and 67% less in the first 48 h than patients treated with fentanyl (p < 0.05). In contrast, a study by Lynn et al. [39] in infants and toddlers in the postoperative setting found no significant differences between the ketorolac treatment groups (0.5 and 1 mg/kg) and placebo controls in terms of cumulative morphine doses used or the need for additional morphine boluses in the 12-h postoperative period.

Pain scores were reported in four of the six studies, with three of these finding no significant differences in pain between treatment and control groups [37, 38, 41]. The remaining study comparing nalbuphine patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) + ketorolac 60 mg via infusion found that that the combination was associated with significantly improved pain scores on the day of operation and days 1 and 2 postoperatively compared with intramuscular meperidine (all p < 0.01) [40]. Additionally, a study by Jo et al. [37] of children who underwent ureteroneocystostomy found significantly fewer incidents of bladder spasms, a treatment-associated symptom, in children treated with ketorolac than in those treated with fentanyl. None of these studies reported significant differences in AEs between the treatment and control groups, including treatment-associated AEs such as postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) or bleeding [36,37,38,39,40].

5 Ketoprofen

Ketoprofen is an NSAID that is available only by prescription in the USA as a generic; branded products (e.g., Actron, Oruvail, Orudis, Orudis KT) have been discontinued [42]. A total of five studies evaluated the opioid-sparing and analgesic effects of ketoprofen in children; a summary of the results from those studies is shown in Table 3 [43,44,45,46,47]. A single study examined intravenous ketoprofen 1 mg/kg versus placebo in children undergoing pectus surgery [46], whereas the rest of the trials tested ketoprofen in children who underwent tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy [43,44,45, 47]. Two studies compared a single dose of intravenous ketoprofen 25 mg with ketoprofen 25 mg via other routes: Tuomilehto and Kokki (intravenous vs. intramuscular ketoprofen) [47] and Kokki et al. (intravenous vs. rectal ketoprofen) [44].

Two of the ketoprofen studies assessed opioid-sparing effects in the context of PCA morphine [46] or fentanyl use [43], whereas the other trials assessed the use of fentanyl [44, 47] and oxycodone titrated to observed pain levels [45] as rescue analgesics. Overall, four of the five studies found reductions in opioid consumption in children treated with ketoprofen [43, 44, 46, 47], whereas the final study reported a nonsignificant reduction in rescue oxycodone use associated with ketoprofen in children [45]. In one of the two studies that assessed opioid consumption by PCA, ketoprofen was associated with a 27% reduction in morphine consumption compared with placebo [46]. In the other study, ketoprofen use was associated with 31% fewer PCA requests versus placebo during the first 6 h post surgery, although the total dose of fentanyl delivered was not significantly different [43].

Ketoprofen was associated with a reduction in opioid requirements regardless of the mode of administration. Kokki et al. [44] found that ketoprofen was associated with a significantly lower proportion of patients needing rescue fentanyl for pain, and the number of fentanyl doses was lower when ketoprofen was given either intravenously or rectally versus placebo. Likewise, Tuomilehto and Kokki [47] found similar and significant reductions in the number of doses of rescue fentanyl required in children receiving ketoprofen either intravenously or intramuscularly compared with placebo-treated children.

Three trials reported significant improvements in pain scores in children treated with ketoprofen compared with placebo [43, 46, 47]; two studies found no significant difference in pain scores between treatment and control groups [44, 45]. In addition, ketoprofen was associated with significantly improved pain scores compared with tramadol [43]. Overall, none of the studies revealed significant differences in rates or severity of AEs of interest such as nausea, vomiting, and sedation [43,44,45,46,47], but one single trial did find significantly greater intraoperative blood loss in patients treated with ketoprofen than in those receiving placebo [43].

6 Diclofenac

Diclofenac is an NSAID that is commonly used for treating acute pain in children [48]. Four studies in our review examined pediatric use of diclofenac and are summarized in Table 4. All of these studies were conducted in children undergoing tonsillectomy [49,50,51,52], and two of them reported opioid-sparing outcomes. Öztekin et al. [50] evaluated preoperative diclofenac 1 mg/kg compared with no preemptive analgesic in the background of PCA analgesia and found morphine consumption decreases of 23% in the post-anesthesia care unit (p = 0.012) and 42% on the ward (p = 0.021) compared with no preemptive treatment. Likewise, the use of preemptive diclofenac was associated with significantly improved pain scores over those in the control group during the first hour after surgery; no significant differences in AEs between the two treatment groups were noted. Rhendra Hardy et al. [52] examined the consumption of intravenous meperidine (pethidine) as rescue medication among children administered diclofenac 1 mg/kg rectally before surgery or 2% topical viscous lidocaine (lignocaine) applied to the tonsillar bed at the end of surgery. No significant differences in meperidine use were noted over 24 h except at the 2-h postoperative time point, where the difference favored topical lidocaine (lignocaine). This study found no difference in pain scores between the two groups; no safety outcomes were reported [52].

The remaining trials of diclofenac tested the NSAID as part of a multimodal analgesic therapy and did not assess outcomes related to opioid consumption. El-Fattah and Ramzy [49] evaluated the analgesic efficacy of a preoperative combination of diclofenac, acetaminophen, and tramadol and found that the combination was associated with significantly reduced pain scores in the first 6 h after tonsillectomy (p < 0.05) versus the control (i.e., local anesthetic infiltration of the peritonsillar region). Rawlinson et al. [51] assessed perioperative administration of a combination of diclofenac 1–2 mg/kg rectally + fentanyl 1–2 µg/kg intravenously versus codeine 1.5 mg/kg intramuscularly as part of an institutional analgesic strategy. There were no differences in postoperative analgesic requirements among the two groups. Maximal pain scores and incidences of PONV were similar in both treatment groups [51].

7 Limitations

It should be noted that review and interpretation of the published data were limited by inconsistencies and differences in drug dosages and regimens employed among the reviewed studies. Likewise, the different outcomes used for assessing efficacy and the different analytic methods conducted limit the ability to make comparisons between NSAIDs. Additionally, our searches were limited to a single database (PubMed). Expanding the searches to other databases may have resulted in the identification of additional relevant references.

Because patients included in this review were treated for pain related to traumatic injury (e.g., bone fracture) or surgical procedures (e.g., tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, pectus surgery, Nissen fundoplication, appendectomy), these results may not be applicable to children experiencing pain in other contexts. This is especially true for children with a suspected underlying infection and/or in those who are dehydrated and at risk for the development of renal impairment. Our review of the literature indicates that only two pediatric NSAID studies, both testing ibuprofen, enrolled more than 100 patients in both treatment and control groups; five trials reviewed included ≤ 20 patients in the treatment and control groups, limiting the power to identify severe but rare side effects of NSAIDs. This was not unexpected given the complexities and inherent challenges of conducting large clinical trials in pediatric populations, and it highlights the importance of well-designed smaller trials in contributing meaningful data in a timely manner in this patient population. Nonetheless, studies in larger populations of pediatric patients are warranted and should be considered for future research. Such studies would also allow clinicians and institutions to have greater confidence in the efficacy and safety of NSAIDs in pain management strategies for the pediatric population.

8 Conclusions

This narrative review details published clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of NSAIDs in children requiring surgical procedures or after traumatic injury. Overall, our review of the literature suggests that NSAIDs are generally safe and effective, can reduce opioid requirements, do not compromise pain control, and are subsequently associated with similar or reduced frequencies of opioid-related AEs, such as nausea and vomiting, in pediatric patients. Healthcare providers should be aware of the potential for increased intraoperative blood loss with ketoprofen or other NSAIDs. The studies evaluated for this review support a positive benefit/risk profile of pediatric NSAID use for traumatic pain conditions or post-surgically, including consideration as an alternative to opioids, an area that deserves further study.

References

Taylor EM, Boyer K, Campbell FA. Pain in hospitalized children: a prospective cross-sectional survey of pain prevalence, intensity, assessment and management in a Canadian pediatric teaching hospital. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13(1):25–32. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/478102.

Segerdahl M, Warrén-Stomberg M, Rawal N, Brattwall M, Jakobsson J. Children in day surgery: clinical practice and routines. The results from a nation-wide survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(6):821–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01669.x.

Lee JY, Jo YY. Attention to postoperative pain control in children. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2014;66(3):183–8. https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2014.66.3.183.

Voepel-Lewis T, Wagner D, Burke C, Tait AR, Hemberg J, Pechlivanidis E, et al. Early adjuvant use of nonopioids associated with reduced odds of serious postoperative opioid adverse events and need for rescue in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(2):162–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12026.

Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2287–98. https://doi.org/10.2147/jpr.S144066.

Bell TM, Raymond J, Vetor A, Mongalo A, Adams Z, Rouse T, et al. Long-term prescription opioid utilization, substance use disorders, and opioid overdoses after adolescent trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(4):836–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000002261.

Bennett KG, Harbaugh CM, Hu HM, Vercler CJ, Buchman SR, Brummett CM, et al. Persistent opioid use among children, adolescents, and young adults after common cleft operations. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(7):1697–701. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000004762.

Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM, McCabe SE, Voepel-Lewis T, Englesbe MJ, et al. Persistent opioid use among pediatric patients after surgery. Pediatrics. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2439.

Voepel-Lewis T, Marinkovic A, Kostrzewa A, Tait AR, Malviya S. The prevalence of and risk factors for adverse events in children receiving patient-controlled analgesia by proxy or patient-controlled analgesia after surgery. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(1):70–5. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fa9e.

Milani GP, Benini F, Dell’Era L, Silvagni D, Podesta AF, Mancusi RL, et al. Acute pain management: acetaminophen and ibuprofen are often under-dosed. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(7):979–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2944-6.

Polomano RC, Fillman M, Giordano NA, Vallerand AH, Nicely KL, Jungquist CR. Multimodal analgesia for acute postoperative and trauma-related pain. Am J Nurs. 2017;117(3 Suppl 1):S12–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000513527.71934.73.

Michelet D, Andreu-Gallien J, Bensalah T, Hilly J, Wood C, Nivoche Y, et al. A meta-analysis of the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for pediatric postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(2):393–406. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e31823d0b45.

Elia N, Lysakowski C, Tramer MR. Does multimodal analgesia with acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, or selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and patient-controlled analgesia morphine offer advantages over morphine alone? Meta-analyses of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(6):1296–304. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200512000-00025.

Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, Rosenberg JM, Bickler S, Brennan T, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008.

Motov S, Strayer R, Hayes BD, Reiter M, Rosenbaum S, Richman M, et al. The treatment of acute pain in the emergency department: a white paper position statement prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(5):731–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.01.020.

Rainsford KD. Ibuprofen: pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Inflammopharmacology. 2009;17(6):275–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-009-0016-x.

Wong I, St John-Green C, Walker SM. Opioid-sparing effects of perioperative paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(6):475–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12163.

Bennani-Baiti AA, Benbouzid A, Essakalli-Hossyni L. Cervicofacial cellulitis: the impact of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A study of 70 cases. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2015;132(4):181–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2015.06.004.

Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2253–65. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1600673.

Poddighe D, Brambilla I, Licari A, Marseglia GL. Ibuprofen for pain control in children: new value for an old molecule. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(6):448–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000001505.

de Martino M, Chiarugi A, Boner A, Montini G, De’ Angelis GL. Working towards an appropriate use of ibuprofen in children: an evidence-based appraisal. Drugs. 2017;77(12):1295–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0751-z.

Motrin Suspension 100 mg/5 mL [package insert]. Fort Washington: McNeil Pediatrics; 2007.

Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, Gaboury I, Passi B. A randomized, controlled trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):460–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-1347.

Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, Lyon R, Brousseau DC, Kim MK. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(4):553–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.06.005.

Friday JH, Kanegaye JT, McCaslin I, Zheng A, Harley JR. Ibuprofen provides analgesia equivalent to acetaminophen-codeine in the treatment of acute pain in children with extremity injuries: a randomized clinical trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(8):711–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00471.x.

Koller DM, Myers AB, Lorenz D, Godambe SA. Effectiveness of oxycodone, ibuprofen, or the combination in the initial management of orthopedic injury-related pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(9):627–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e31814a6a39.

Le May S, Gouin S, Fortin C, Messier A, Robert MA, Julien M. Efficacy of an ibuprofen/codeine combination for pain management in children presenting to the emergency department with a limb injury: a pilot study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(2):536–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.06.027.

Le May S, Ali S, Plint AC, Masse B, Neto G, Auclair MC, et al. Oral analgesics utilization for children with musculoskeletal injury (OUCH trial): an RCT. Pediatrics. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0186.

Poonai N, Bhullar G, Lin K, Papini A, Mainprize D, Howard J, et al. Oral administration of morphine versus ibuprofen to manage postfracture pain in children: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 2014;186(18):1358–63. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.140907.

Kelly LE, Sommer DD, Ramakrishna J, Hoffbauer S, Arbab-Tafti S, Reid D, et al. Morphine or ibuprofen for post-tonsillectomy analgesia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):307–13. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1906.

Moss JR, Watcha MF, Bendel LP, McCarthy DL, Witham SL, Glover CD. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled, single dose trial of the safety and efficacy of intravenous ibuprofen for treatment of pain in pediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24(5):483–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.12381.

Pickering AE, Bridge HS, Nolan J, Stoddart PA. Double-blind, placebo-controlled analgesic study of ibuprofen or rofecoxib in combination with paracetamol for tonsillectomy in children. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88(1):72–7.

Viitanen H, Tuominen N, Vaaraniemi H, Nikanne E, Annila P. Analgesic efficacy of rectal acetaminophen and ibuprofen alone or in combination for paediatric day-case adenoidectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91(3):363–7.

Poonai N, Datoo N, Ali S, Cashin M, Drendel AL, Zhu R, et al. Oral morphine versus ibuprofen administered at home for postoperative orthopedic pain in children: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2017;189(40):E1252–8. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170017.

McNicol ED, Rowe E, Cooper TE. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD012294. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012294.pub2.

Carney DE, Nicolette LA, Ratner MH, Minerd A, Baesl TJ. Ketorolac reduces postoperative narcotic requirements. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(1):76–9. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpsu.2001.20011.

Jo YY, Hong JY, Choi EK, Kil HK. Ketorolac or fentanyl continuous infusion for post-operative analgesia in children undergoing ureteroneocystostomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55(1):54–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02354.x.

Keidan I, Zaslansky R, Eviatar E, Segal S, Sarfaty SM. Intraoperative ketorolac is an effective substitute for fentanyl in children undergoing outpatient adenotonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14(4):318–23. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01212.x.

Lynn AM, Bradford H, Kantor ED, Seng KY, Salinger DH, Chen J, et al. Postoperative ketorolac tromethamine use in infants aged 6–18 months: the effect on morphine usage, safety assessment, and stereo-specific pharmacokinetics. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(5):1040–51, tables of contents. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000260320.60867.6c.

Shin D, Kim S, Kim CS, Kim HS. Postoperative pain management using intravenous patient-controlled analgesia for pediatric patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12(2):129–33.

Neri E, Maestro A, Minen F, Montico M, Ronfani L, Zanon D, et al. Sublingual ketorolac versus sublingual tramadol for moderate to severe post-traumatic bone pain in children: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(9):721–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-303527.

Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. US Food and Drug Administration. 2017. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=BasicSearch.process. Accessed 10 Apr 2020.

Antila H, Manner T, Kuurila K, Salantera S, Kujala R, Aantaa R. Ketoprofen and tramadol for analgesia during early recovery after tonsillectomy in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16(5):548–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01819.x.

Kokki H, Tuomilehto H, Tuovinen K. Pain management after adenoidectomy with ketoprofen: comparison of rectal and intravenous routes. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85(6):836–40.

Kokki H, Salonen A. Comparison of pre- and postoperative administration of ketoprofen for analgesia after tonsillectomy in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12(2):162–7.

Rugyte D, Kokki H. Intravenous ketoprofen as an adjunct to patient-controlled analgesia morphine in adolescents with thoracic surgery: a placebo controlled double-blinded study. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(6):694–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.11.001.

Tuomilehto H, Kokki H. Parenteral ketoprofen for pain management after adenoidectomy: comparison of intravenous and intramuscular routes of administration. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46(2):184–9.

Standing JF, Tibboel D, Korpela R, Olkkola KT. Diclofenac pharmacokinetic meta-analysis and dose recommendations for surgical pain in children aged 1–12 years. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21(3):316–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03509.x.

El-Fattah AM, Ramzy E. Pre-emptive triple analgesia protocol for tonsillectomy pain control in children: double-blind, randomised, controlled, clinical trial. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(4):383–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215113000364.

Öztekin S, Hepaguslar H, Kar AA, Ozzeybek D, Artikaslan O, Elar Z. Preemptive diclofenac reduces morphine use after remifentanil-based anaesthesia for tonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12(8):694–9.

Rawlinson E, Walker A, Skone R, Thillaivasan A, Bagshaw O. A randomised controlled trial of two analgesic techniques for paediatric tonsillectomy. Anaesthesia. 2011;66(10):919–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06851.x.

Rhendra Hardy MZ, Zayuah MS, Baharudin A, Wan Aasim WA, Shamsul KH, Hashimah I, et al. The effects of topical viscous lignocaine 2% versus per-rectal diclofenac in early post-tonsillectomy pain in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(4):374–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.01.005.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Francois Angoulvant, PhD, for his critical review of this manuscript during its development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Medical writing support was provided by John H. Simmons, MD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and was funded by Pfizer. On 1 August 2019, Pfizer Consumer Healthcare became part of GSK Consumer Healthcare.

Conflict of interest

MC has participated in advisory boards for Pfizer Consumer Healthcare and Heron Pharma and has served as a speaker for Mallinckrodt.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Previous presentation

Data previously presented at PAINWeek 2018, September 4–8, 2018, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cooney, M.F. Pain Management in Children: NSAID Use in the Perioperative and Emergency Department Settings. Pediatr Drugs 23, 361–372 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-021-00449-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-021-00449-z