Abstract

Objective

We aimed to identify the health and quality-of-life research priorities of Australians with diabetes or family members.

Methods

Through an iterative, three-step, online survey process we (1) qualitatively generated research topics (long list) in response to one question “What research is needed to support people with diabetes to live a better life?”; (2) determined the most important research questions (short list); and (3) ranked research questions in order of importance (priorities). We aimed to recruit N = 800 participants, with approximate equal representation of diabetes type and family members.

Results

Participants (N = 661) were adults (aged 18+ years) in Australia with a self-reporting diagnosis of diabetes (type 1, n = 302; type 2, n = 204; prior/current gestational, n = 58; less common types, n = 22, or a family member, n = 75). Retention rates for Surveys 2 and 3 were 47% (n = 295) and 50% (n = 316), respectively. From 1549 open-text responses, 25 topics and 125 research questions were identified thematically. Research priorities differed by cohort, resulting in specific lists developed and ranked by each cohort. The top-ranked research question for the type 1 diabetes cohort was “How can diabetes technology be improved …?” and for the type 2 diabetes cohort: “How can insulin resistance be reversed …?”. One question was common to the final lists of all cohorts: “What are the causes or triggers of diabetes?” Within cohorts, the top priorities were perceived as being of similar importance.

Conclusions

The research priorities differ substantially by diabetes type and for family members. These findings should inform funding bodies and researchers, to align future research and its communication with community needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

People with diabetes and their families can make a significant contribution in defining diabetes research agendas, which may lead to a more appropriate allocation of limited funding. |

In a rigorous consultation process, Australians with diabetes or family members raised and prioritised research topics they considered important for a better life with diabetes. The priorities covered a broad range of topics and differed according to the type of diabetes or for families. |

The consultation identified gaps in the research and dissemination of existing research evidence. |

These findings should inform funding bodies and researchers, to align future research and its communication with community needs. |

1 Introduction

Diabetes is a global health priority, presenting a significant challenge to the health and well-being of individuals living with the condition, their families and societies [1, 2]. In Australia, more than 1.5 million people have diabetes, with around 9% with type 1 diabetes (T1D), 85% with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and 3% with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) [3]. In 2018–19, the direct diabetes costs to the Australian health system were estimated at $3 billion, with 40% spent on hospital services [4]. Australian diabetes research is funded mostly by government bodies (e.g. National Health and Medical Research Council, Medical Research Future Fund [5]) and peak organisations (e.g. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, Diabetes Australia). Over the past decade, the National Health and Medical Research Council funding for diabetes research exceeded AUD$500 million (~9% total funding) [6]. To date, the Medical Research Future Fund has invested more than AUD$100 million in diabetes research projects [7]. However, in Australia [8, 9] and worldwide, diabetes research remains underfunded, relative to some other conditions [10,11,12], and particularly so for behavioural and psychosocial research [13]. Thus, it is imperative that limited research funding responds directly to the needs and interests of the community living with diabetes. In contrast, a disparity may exist between funded research and the priorities of those with the condition [14].

Traditionally, health research agendas are set by policy makers, informed by ‘experts’ (researchers, clinicians, funding bodies, peak bodies, industry), based on gaps in scientific evidence, established through evidence reviews. However, the past two decades have seen a growing recognition of the importance of including the views of those with lived experience of a condition, in defining research agendas and improving health services. The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council 2016 statement on ‘consumer and community involvement’ (CCI) recognises that the community can “add value to health and medical research, and they have the right and responsibility to do so” [15]. Similar guidance has been published by funding bodies and health organisations elsewhere, and a key consideration for CCI includes the provision of input into the formulation and development of research questions [16].

People with diabetes and family members or carers can make a significant contribution to identify and prioritise relevant research topics, as well as how the research is conducted [17, 18]. Their involvement may lead to a more appropriate allocation of limited research funding, enhanced research engagement and participant retention, as well as the development, implementation and uptake of more relevant, effective and acceptable interventions. A review exploring the benefits of CCI in diabetes research found that the lived experiences of people with diabetes were instrumental in developing and conducting relevant and accessible interventions for diabetes self-management [17]. Shared ownership (i.e. reciprocal relationships between researchers, people with diabetes and the wider community) was associated with high retention and stakeholder engagement.

While several diabetes research priority-setting activities have been undertaken to date, and outcomes published, the level of CCI is variable [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. In the UK, the James Lind Alliance (JLA) has established the research priorities of people with T1D [20], T2D [23] and women experiencing diabetes (T1D, T2D or GDM) during pregnancy [19]. These studies have drawn on large samples of the community with lived experience as well as carers to inform and prioritise research questions, in addition to inviting clinician input and agreement, and the validation of priorities against the existing literature. Identified priorities (across cohorts) relate to the prevention and successful management of diabetes (including treatments and technologies), prevention of complications and the role of emotional well-being. These stakeholder initiatives have informed the Diabetes UK research strategy, including dedicated research funding calls [26]. However, findings from consultations in the UK cannot be assumed to be relevant to the Australian (nor other international) contexts owing, for example, to differences in the healthcare systems, access to and subsidies for treatments, diversity in population ethnicities and underserved groups. In Australia, limited prioritisation of diabetes research questions has been conducted. For example, one study established a list of the top ten research questions to improve diabetes-related foot health utilising a Delphi method inviting both community and clinician perspectives [25]. Thus, there remains a need for a comprehensive view of community perspectives on diabetes research priorities. Further, it is likely that priority research questions differ between clinicians and those with lived experience [24], and a greater focus on CCI in the elicitation of research priorities, without required agreement with clinicians or other stakeholders, is warranted.

Thus, to shape the Australian diabetes research agenda for the next decade, it is crucial to engage people living with diabetes and their family members to identify salient and applied research questions. Understanding what matters to Australians with diabetes has the potential to influence recommendations for future impactful research to address unmet needs. Through stakeholder consultations with adults with diabetes and family members, we aimed to identify research priorities they consider important for improving the health and quality of life of Australians with diabetes.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

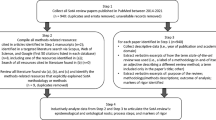

We used an iterative three-step survey process to: (1) qualitatively generate research topics (long list); (2) determine important research questions (short list); and (3) rank research questions in order of importance (priorities). Surveys took place between November 2021 and July 2022 (Fig. 1). The study design was informed by a review of existing diabetes research priority-setting publications [19,20,21,22,23,24,25], and methods to achieve to a priority-setting consensus [27]. Consistent with the JLA method [28], the current study involved establishing a steering group, generating a long list of research questions, summarisation of questions into a short list and the identification of priority questions for publication. However, the study-specific approach employed, which responds to the aims of the study and project resourcing, differs from JLA in several notable ways: (1) participants are limited to those with lived experience of diabetes or family members. Unlike the JLA approach, we did not aim to achieve agreement in priorities between the community and health professionals or any other stakeholders; (2) community priorities were not informed by, nor validated against, gaps in the existing literature; and (3) the generation and prioritisation of research questions was conducted entirely via an online survey, without further workshops or discussion with participants. The research received ethics approval from the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2021-268).

2.2 Steering Group

A steering group was established, with expressions of interest invited via diabetes-related social media and websites. A member of the research team (SRG) contacted the n = 25 respondents to provide more detailed information about the project and the role of the steering group, and also to clarify the respondents understanding and expectations. With the intention to establish a diverse group, seven members were selected, with reasonable representation across: gender (n = 3 women), age (27–61 years); cohort (T1D: n = 2; T2D: n = 2, GDM: n = 1; latent autoimmune diabetes in adults: n = 1; family member [FM]: n = 1); geographical location (metro, regional and rural areas; limited to Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland); and prior experience in advisory boards or stakeholder consultation roles (n = 3). The group met on three occasions via Zoom, and provided further feedback via e-mail or telephone throughout the project to guide study design, survey development, and the interpretation and dissemination of findings. Specifically, the steering group reviewed all recruitment and study materials with refinements made based on their feedback; collaboratively developed, together with the researchers, the open-ended question employed in Survey 1 (see below); piloted all surveys; supported interpretation and reporting with involvement in the drafting of a lay report for community dissemination; and were invited to co-author the current article. As a token of appreciation, stakeholders received an AUD$50 voucher each, per meeting attended.

2.3 Survey Participants

Inclusion criteria were self-reporting a diabetes diagnosis (any type, including prior/current experience of GDM), or being a FM/carer of someone with diabetes, aged 18+ years and living in Australia. We aimed to recruit N = 800 participants, with approximate equal representation of people with T1D, T2D, current/prior GDM and FM, as well as representation (across participant groups) of First Nations people (n > 50). Conservatively, we allowed for ≥ 60% attrition by Survey 3 [23].

2.4 Recruitment

Recruitment was primarily via the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS); an initiative of the Australian Government administered by Diabetes Australia providing >1.4 million registrants with diabetes access to services, support and subsidised diabetes products. E-mail invitations were sent to a random sample of N = 23,250 adult registrants who had consented to receive research invitations, based on an anticipated 8% response rate [29], and subsequent boosting because of the observed lower response rate. The sample was stratified by cohort (and over-sampled young adults with T2D), and by state/territory (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). The survey was also promoted via diabetes-related websites and social media (Twitter/Facebook), and through the researchers’ affiliated e-newsletters and participant distribution lists, as relevant. Social media and online promotions included open calls as well as tailored messaging for specific populations of interest (e.g. people with GDM; FM). Finally, to engage with First Nations people, culturally appropriate advertising and materials were developed and disseminated (e.g. via Koori mail). Promotions directed participants to the study website for further information.

2.5 Data Collection and Analysis

Potential participants were directed to complete eligibility screening items, access a plain language statement and provide informed consent, all online via Qualtrics™. Eligible consenting participants were then immediately directed to complete Survey 1, with subsequent e-mail invitations to complete Surveys 2 and 3 (hosted via Qualtrics™) (Fig. 1), with an estimated completion time of <15 minutes each. Consent was reconfirmed before entering each of the online surveys. Survey data were linked via e-mail address. Survey content is provided in the ESM. After completing each survey, participants were eligible for a prize draw to win one of two AUD$100 vouchers.

2.5.1 Survey 1: Generating Research Topics (Long List)

Participants were invited to provide up to three qualitative responses to the open-ended question: ‘Whilst researchers are working hard to find a cure, what other research do you think is needed to support people with diabetes to live a better life?’ In addition, demographic data (including age, sex, Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander origin, education, employment, country of birth, language spoken at home, state and location) and information about diabetes (diabetes type, age at onset, treatment) were collected. Participants were asked for their e-mail address, to allow sending invitations for the next two surveys and to enter a prize draw.

Analysis: An inductive analysis was undertaken in QSR NVivo 12 employing a thematic template approach [30]. Based on the first 100 responses, SRG developed the initial coding framework and reviewed and refined it together with CH and EHT (all with expertise in qualitative analysis). Through a consensus, the framework was finalised and applied independently to all responses by SRG, and double coded by CH or EHT. Identified topics were the basis to formulate research topics/questions, with direct quotes used where possible. Content and phrasing were reviewed and agreed by the steering group and researchers.

2.5.2 Survey 2: Determining Most Important Research Questions (Short List)

Participants providing an e-mail address in Survey 1 were invited to complete Survey 2, in which the long list of identified research questions was presented. They were asked to select up to ten questions most important to them. Respondents could add additional questions in an open-text field. Participants were provided the opportunity to view their short-listed questions prior to submission and were prompted to consider refining should they have selected more than ten questions. However, survey logic did not allow for forced selection of ten questions and participants who selected (or qualitatively reported) fewer or greater than ten questions were maintained.

Analysis: Descriptive statistics were calculated for the whole group and by cohort (i.e. T1D, T2D, GDM, less common diabetes types, FM). The ten questions (or more in the case of equal percentages) with the highest proportion of participants indicating these questions as important were included in the short list presented in Survey 3. Free-text responses were considered against existing research questions to identify where they overlap or present unique suggestions. Where overlapping, the Survey 1-generated research question was selected for that participant (if not already done, and regardless of the number of original selected items). Unique questions were added to the long list of questions generated but not taken forward in Survey 3.

2.5.3 Survey 3: Ranking Research Questions (Priorities)

Participants were invited to rank the short list of approximately ten research questions in descending order of importance to them. Prior to Survey 3, minor textual refinements were made to some questions presented to improve readability (see Table 3 and the ESM) and consideration was given to the merging of research questions where repetition occurred within the top approximately ten lists (i.e. multiple highly endorsed items within a single research topic on conceptually related questions).

Analysis: Each participant’s rankings were allocated weighted scores (1–10), where most important = 10 points and least important = 1 point. Weighted scores were summed for each question per cohort, to determine overall rankings.

3 Results

In total, 661 participants completed Survey 1 (83% of target sample; ESM), including 302 participants with T1D (46% using insulin pump or commercial/self-built closed loop; living with diabetes for a mean ± standard deviation of 23 ± 17 years), 204 participants with T2D (29% insulin-treated; diabetes duration: 14 ± 9 years), 58 women with experience of GDM (77% not currently pregnant with GDM; among those with a current GDM diagnosis, 53% insulin treated), 22 participants with less common diabetes types (64% insulin treated, diabetes duration: 13 ± 13 years) and 75 FM (69% a parent to someone with diabetes; 87% a FM to person with T1D). All states and territories were represented (Table 1). Most participants (n = 434; 66%) reported accessing the survey via an NDSS direct invitation (~ 2% response rate).

3.1 Generating Research Questions

Survey 1 generated 1549 unique responses, in various formats; phrased as questions, statements or short paragraphs. A thematic analysis resulted in 25 unique topics (Table 2), comprising 125 research questions. A full list of the research questions is provided in the ESM. The research topic with the highest number of discrete questions generated was ‘food and physical activity’ (n = 17), with all other research topics incorporating between two and nine research questions.

3.2 Determining the Most Important Research Questions

In Survey 2, 295 (47%) participants responded (Table 1). A third of participants endorsed either greater (n = 35; 12%) or fewer (n = 65;22%) than ten research questions (range: 1–44). Additional question(s) were qualitatively reported by n = 51 participants, for which the vast majority (n = 49) reported questions that were consistent with one or more of the 125 existing question(s). Two new questions were identified: (1) ‘How can we involve people with diabetes and improve respect for the lived experience in research, including the development of new treatments and technologies?’ and (2) ‘What is the impact of diabetes on sexual health and desire?’.

Each of the 125 questions generated from Survey 1 was prioritised by at least one participant. The ESM displays the proportion of participants who selected each question by cohort. As research priorities differed by cohort, unique lists were developed for T1D, T2D, GDM, less common types and FM. Short lists for GDM, less common diabetes types and FM consisted of 11 or 12 research questions, as two or three questions shared the same proportion of endorsements. To reduce repetition within the final short lists, four highly related questions on the topic of ‘glucose monitoring & insulin delivery technologies’ were merged for the T1D and FM cohorts, and two questions on the topic of ‘food & physical activity’ topic were merged for the T2D cohort. The final short-listed research priorities are detailed in Table 3 and the ESM.

Of the 125 questions, 37 were included in one or more of the short lists, representing 20 of the 25 original topics (Table 2). The number of research topics represented within short lists, per cohort, ranged from seven (T2D) to ten (FM). One research topic (‘causes’) and question (‘What are the causes or triggers of diabetes?’) was consistently short-listed across all cohorts. Other research topics with short-listed questions observed across most cohorts included ‘cure, advanced treatments & clinical research’ (T1D, T2D, less common types and FM); ‘food and physical activity’ (T2D, GDM, less common types and FM); ‘glucose monitoring & insulin delivery technologies’ (T1D, GDM and FM), and ‘preventing diabetes’ (T1D, GDM and FM). Three research questions on the topics of ‘government funding & financial costs’, ‘food & physical activity’ and ‘reproductive health & diabetes in pregnancy’ were each short-listed for participants with T1D, T2D and GDM, respectively. All other topics were represented by two or fewer questions per cohort.

3.3 Ranking Research Questions

In Survey 3, 316 (50%) participants responded (Table 1). The highest ranked research questions for participants with T1D was ‘How can diabetes technology be improved …?’, and for T2D ‘How can insulin resistance be reversed …?’ (Table 3). Research priorities for other diabetes types and FM, where sample sizes were smaller, are shown in the ESM. For women with GDM (n = 15), the most important question was ‘What are the short- and long-term impacts of gestational diabetes on the baby/child?’. For people with less common diabetes types (n = 9), the most common reported research question was ‘What is the link between diabetes and other health conditions?’. For FM, the most important question was ‘How can diabetes technologies be improved …?’, similar to the highest priority for adults with T1D.

4 Discussion

Through a rigorous and iterative research design, involving guidance from a community steering group, this study identified the research priorities of adults living with (all types of) diabetes and their FM in Australia. This study generated 127 unique research questions (125 from Survey 1, plus two further identified in Survey 2), covering 25 broad research topic areas, considered important by the community for a better life with diabetes. The volume of research questions and topics identified (all prioritised by at least one participant in Survey 2), as well as the relatively small observed differences in rankings (weighted scores in Survey 3) suggest diverse research interests and unmet needs. Taken together, these findings indicate that people living with or affected by diabetes in Australia believe that better health and quality of life could be achieved through research designed to reduce the everyday burden of living with diabetes. Substantial divergence in the prioritised research questions of adults with T1D, T2D and GDM, and their FM, supports the need for cohort-specific research agendas (with exceptions discussed below).

For participants with T1D (and FM), the highest ranked research priority focused on investigating how glucose monitoring and insulin-delivery technologies can be improved to reduce the burden of managing diabetes. In addition to effectiveness, participants suggested that research should focus on how technologies can make diabetes management easier and how technologies can be better integrated, more environmentally friendly and/or more accessible. Similar findings were observed in the UK JLA process, whereby the top three T1D research priorities referred to the availability of discrete continuous glucose monitors and the effectiveness of insulin pump devices and closed loop systems [20]. However, Australians with T1D also prioritised research to reduce the financial burden of diabetes through increased, timely and affordable access to advanced technologies, likely reflecting the local health system. Relatedly, the International Diabetes Federation have highlighted universal access to insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors as one of four key interventions that could reduce the negative impacts of T1D worldwide [31]. Alongside mounting scientific evidence for the clinical and psychosocial benefits of advanced technologies in the management of T1D [32, 33], the research priority setting illustrates strong community interest in continued research efforts to improve device effectiveness, convenience, acceptability and accessibility.

Commonality was observed between priorities for those with T1D and FM, with six consistently reported priorities across the two cohorts. This might be expected given that the latter cohort largely reported being parents to someone with T1D. For example, both cohorts prioritised research into raising the public awareness of diabetes, including the differences in diabetes types, their causes, symptoms and treatments. This is consistent with the findings of a recent World Health Organization key informant survey, which identified perceived needs for the media to differentiate between diabetes types, and for an increased awareness of the signs and symptoms of T1D [34]. Current study participants with T1D and FM suggested that a greater public awareness could also enable improved first-aid response to those experiencing severe hypoglycaemia. In contrast to those with T1D, FM also prioritised, for example, research aimed at increasing support in schools for children with T1D, as well as improvements to early diabetes screening.

Among participants with T2D, the highest ranked research priority focused on the reversal of insulin resistance, with several other priorities seeking to identify the most effective diets, exercise plans and supports to achieve T2D remission and/or weight loss consistent with the research priorities of adults with T2D in the UK [23]. Increasing evidence suggests T2D remission (i.e. reduction in HbA1c to ≤ 6.5% without the use of glucose-lowering medications) is possible for some when adopting an intensive weight management programme following diagnosis [35,36,37]. Such findings have garnered widespread scientific, health and media attention, as well as apparent interest from the broader T2D community. Qualitative responses to Survey 1 suggested some participants did not understand what T2D remission is or involves. Further, average T2D duration and medication status (29% insulin treated) indicate remission may not be achievable or sustainable for most participants with T2D in the current study [38]. Thus, there is a clear need for and interest in greater communication and education about T2D remission, in addition to research on this topic.

Participants with GDM prioritised research that seeks to better understand the impacts of diabetes on their child (during pregnancy and in the long term). Prior qualitative research among those with GDM has commonly identified heightened fear and health concerns for their child [39, 40]. However, investigation and minimisation of risks to the child were ranked 4th and 11th, respectively, in previous Canadian and UK priority-setting exercises. [19, 22] This point of difference in research priority ranking may be because of the small Australian sample from which GDM research priorities are drawn, the different methods used and/or stakeholders consulted. Consistencies in GDM research priorities across the current Australian, UK and Canadian research priorities include: prevention of future T2D diabetes, mental health and emotional well-being, as well as diet and physical activity [19, 22]. Among the small cohort of participants with less common types of diabetes, prioritised research related to the association of diabetes with other conditions (also prioritised by T1D cohort), as well as the need for improved screening, diagnosis and management of latent autoimmune diabetes in adults and maturity onset diabetes of the young, including increased awareness among health professionals of these types of diabetes.

Investigation of ‘the causes or triggers of diabetes …’ was the only consistently prioritised research question across all cohorts, though not ranked first for any cohort. Despite differing aetiologies, this may reflect the shared complexity, and still limited understanding of the causes, of all types of diabetes. Qualitative responses in Survey 1 indicated that such knowledge gains would ultimately assist in finding a cure for or enable prevention of diabetes. Indeed, research focused on a diabetes cure was also a priority for all cohorts (except GDM), despite Survey 1 question wording specifically asking for research questions beyond that of a cure. Research relating to either prevention or remission was also prioritised across cohorts. Some participants reported seeking a better understanding of the extent to which their diabetes may have been caused by their behaviours (vs factors such as genetics, ageing and the environment). Other research demonstrates that beliefs and attributions about the causes of diabetes (e.g. perceived control/personal responsibility) [41] are associated with internalisation of diabetes stigma by people living with T2D and GDM [42], and has a detrimental impact on public support for funding diabetes healthcare and research [43]. Thus, there is need for careful consideration of how evidence about the causes of diabetes is communicated to support optimal self-management and raise awareness of diabetes risk factors, without perpetuating stigma and its harmful effects [44].

Researchers may use the current study findings to drive a community-informed research programme. It is also hoped that these findings would inform future research funding calls in Australia, as has been seen in the UK following community research priority setting [26]. While some commonality in priorities is observed [19,20,21,22,23,24,25], the relevance of these research questions to community needs and interests within other countries (as well as under-represented sub-populations within Australia and the UK) warrants investigation, with consideration given to the value and appropriateness of a global community-informed diabetes research agenda.

For many of the identified research priorities, published evidence exists. Prioritisation of such research questions among the diabetes community suggests that this evidence may not be disseminated clearly or implemented appropriately (e.g. within healthcare services). Thus, in addition to addressing the community-identified evidence gaps, processes are needed to improve the dissemination and implementation of research findings. Broad public communication of research findings is an ethical responsibility of researchers [45] and a strategic priority of peak bodies [46]. Together, there is opportunity for researchers and diabetes organisations to deliver effective communications tailored to the research questions prioritised by the community. To commence this work, a lay report has been published to communicate findings with the community and be used for further consultations with diabetes organisations and funding bodies. The report can be accessed via the study-specific website (diabetesresearchmatters.com), where future dissemination initiatives will be posted. Beyond this study, and the Australian context, there remains a need for greater attention to investment and CCI in the communication and implementation of diabetes research.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

While the target sample was exceeded for T1D and achieved for T2D, other target samples (e.g. GDM, First Nations people) were not met and the targeted total sample of 800 participants completing Survey 1 was not achieved. Further, a low response rate for NDSS direct invitations was observed: 2% compared with the expected 8% (informed by a national online survey of adults with T1D or T2D conducted in 2015 [29]). However, the rate of response is consistent with more recent online research studies utilising NDSS recruitment and requiring multi-stage participation (e.g. [47]), which may suggest an overall reduction in research participation by registrants.

Guidelines for the minimum number of unique responses or participants in such consultations are limited [28, 48], and previous diabetes research priority-setting initiatives have established priorities based on samples that range from n = 39 to [24] n > 2000 participants [23]. In the current study, we generated 1549 unique responses from more than 600 participants. However, because we treated each cohort’s responses separately to generate cohort-specific lists, the sample size per cohort was effectively reduced. Nonetheless, this data separation was important in acknowledging the unique experiences of each cohort, and the limited potential for the views of any one cohort to be over-represented or under-represented because of unequal samples. Further, the significant similarities between the Australian and UK priorities support the validity of our findings.

Despite the low response rate, our sample included diverse representation of age, gender, states/territories and education levels, though most participants were Australian born with English as their primary language (i.e. not reflecting the cultural diversity of Australian society). Translation of the questions in the most common languages spoken in Australia could have resulted in a more diverse cultural representation and should be considered for future consultations. Despite indigenous representation within the research team, and tailoring recruitment materials and strategies, we did not reach the target sample. Thus, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the research priorities of First Nations people with diabetes in Australia. Additional consultations with culturally diverse groups should be undertaken using appropriate techniques (e.g. using in-language surveys or qualitative community-led approaches), and results compared to the learnings of this initial national consultation. With increasing recognition of the importance of CCI in research worldwide, it is anticipated that the methods employed in the current study may inform priority setting elsewhere, as the current results cannot speak to community interests outside of Australia, nor specific sub-populations within Australia.

The amount and diversity of qualitative data collected in Survey 1 are strengths of the current approach, but the analysis process was time intensive. The time lapse between surveys likely contributed to the observed attrition rate (though at 53%, this was lower than the anticipated 60%), along with the participant burden of the subsequent surveys. To respect the variety of research topics raised, the task for participants in Survey 2 was complex and time consuming, as they were asked to select from a list of 125 questions (categorised into 25 topics). To reduce the burden, a pragmatic decision was taken to ask participants to select the ten most important questions rather than rating the importance of all 125 questions. A ranking was then obtained in the last survey only, limiting data insights beyond the selected approximately top ten per cohort. The long list of research questions generated may have been significantly shorter, and task complexity reduced, if stakeholders were consulted separately per cohort. Our aim to include participants with different types of diabetes as well as FM was ambitious. However, we did not believe it ethical to prioritise one cohort over others, and a strength of this study is its inclusivity, with separate reporting of research priorities for each cohort. This includes FM, whose priorities have previously been combined within diabetes cohorts to reach a consensus, at a consistent moment in time [20, 23].

5 Conclusions

Through a systematic iterative consultation process, we report the cohort-specific research priorities of adults with T1D, T2D, GDM, less common diabetes types and FM in Australia, with only one common priority identified across groups. Within cohorts, the differences in perceived importance between the top priorities are minimal, supporting the need for investment in diverse research programmes to reduce the diabetes burden. Respecting the needs and interests of community, these findings can be used to shape the future research agenda of Australian funding bodies and researchers, and to inform community-focused research dissemination strategies. Further, given the consistency of results with similar priority-setting initiatives in the UK, study findings may have broader relevance with the opportunity to inform international diabetes research funding calls and collaborations.

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 10th ed. Brussels, Belgium. 2021. https://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute. Diabetes: the silent pandemic and its impact on Australia. 2014. https://baker.edu.au/-/media/documents/impact/diabetes-the-silent-pandemic.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

National Diabetes Services Scheme. Diabetes data snapshots: all types of diabetes (September 2023). 2022. https://www.ndss.com.au/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-and-figures/diabetes-data-snapshots/. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health system expenditure. 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/diabetes/contents/impact-of-diabetes/health-system-expenditure. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Gilbert SE, Buchbinder R, Harris IA, Maher CG. A comparison of the distribution of Medical Research Future Fund grants with disease burden in Australia. Med J Aust. 2021;214(3):111-3.e1. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50916.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Research funding statistics and data. 2022. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/funding/data-research/research-funding-statistics-and-data. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Diabetes: Australian facts. 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/diabetes/diabetes/contents/data-gaps-and-opportunities. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Speight J. Behavioural innovation is key to improving the health of one million Australians living with type 2 diabetes. Med J Aust. 2016;205(4):149–51. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja16.00556.

Diabetes Australia. Diabetes research changing lives. Canberra, Australia. 2023. https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/mediarelease/diabetes-research-changing-lives/. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Begum M, Lewison G, Sommariva S, Ciani O, Tarricone R, Sullivan R. European diabetes research and its funding, 2002–2013. Diabet Med. 2017;34(10):1354–60.

Holt R. A crisis in diabetes research funding. Diabet Med. 2017;34(10):1331.

Moses H, Matheson DH, Cairns-Smith S, George BP, Palisch C, Dorsey ER. The anatomy of medical research: US and international comparisons. JAMA. 2015;313(2):174–89.

Jones A, Vallis M, Cooke D, Pouwer F. Review of research grant allocation to psychosocial studies in diabetes research. Diabet Med. 2016;33(12):1673–6.

Boddy K, Cowan K, Gibson A, Britten N. Does funded research reflect the priorities of people living with type 1 diabetes? A secondary analysis of research questions. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016540.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Statement on consumer and community involvement in health and medical research. 2016. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/5091/download?token=c4S6ZKnw. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Aiyegbusi OL, McMullan C, Hughes SE, Turner GM, Subramanian A, Hotham R, et al. Considerations for patient and public involvement and engagement in health research. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):1922–9.

Harris J, Haltbakk J, Dunning T, Austrheim G, Kirkevold M, Johnson M, et al. How patient and community involvement in diabetes research influences health outcomes: a realist review. Health Expect. 2019;22(5):907–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12935.

Ng AH, Quigley M, Benson T, Cusack L, Hicks R, Nash B, et al. Living between two worlds: lessons for community involvement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12:155–7.

Ayman G, Strachan JA, McLennan N, Malouf R, Lowe-Zinola J, Magdi F, et al. The top 10 research priorities in diabetes and pregnancy according to women, support networks and healthcare professionals. Diabet Med. 2021;38(8):e14588. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14588.

Gadsby R, Snow R, Daly AC, Crowe S, Matyka K, Hall B, et al. Setting research priorities for type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29(10):1321–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03755.x.

Bennett WL, Robinson KA, Saldanha IJ, Wilson LM, Nicholson WK. High priority research needs for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Womens Health. 2012;21(9):925–32.

Rees SE, Chadha R, Donovan LE, Guitard AL, Koppula S, Laupacis A, et al. Engaging patients and clinicians in establishing research priorities for gestational diabetes mellitus. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41(2):156–63.

Finer S, Robb P, Cowan K, Daly A, Shah K, Farmer A. Setting the top 10 research priorities to improve the health of people with type 2 diabetes: a Diabetes UK-James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership. Diabet Med. 2018;35(7):862–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13613.

Brown K, Dyas J, Chahal P, Khalil Y, Riaz P, Cummings-Jones J. Discovering the research priorities of people with diabetes in a multicultural community: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(524):206–13.

Perrin BM, Raspovic A, Williams CM, Twigg SM, Golledge J, Hamilton EJ, et al. Establishing the national top 10 priority research questions to improve diabetes-related foot health and disease: a Delphi study of Australian stakeholders. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(2):e002570.

Diabetes UK. New research strategy for the UK aims to transform diabetes care. 2016. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about-us/news-and-views/new-research-strategy-uk-aims-transform-diabetes-care. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Sibbald SL, Singer PA, Upshur R, Martin DK. Priority setting: what constitutes success? A conceptual framework for successful priority setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):1–12.

James Lind Alliance. The James Lind Alliance guidebook V10. 2021. https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook/downloads/JLA-Guidebook-Version-10-March-2021.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Browne JL, Holmes-Truscott E, Ventura AD, Hendrieckx C, Pouwer F, Speight J. Cohort profiles of the cross-sectional and prospective participant groups in the second Diabetes MILES: Australia (MILES-2) study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012926.

Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual Res Psychol. 2015;12(2):202–22.

Federation ID. New global Type 1 Diabetes Index highlights the unmet need of people living with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;192:110123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110123.

Speight J, Choudhary P, Wilmot EG, Hendrieckx C, Forde H, Cheung WY, et al. Impact of glycaemic technologies on quality of life and related outcomes in adults with type 1 diabetes: a narrative review. Diabet Med. 2023;40(1):e14944.

Choudhary P, Campbell F, Joule N, Kar P, Diabetes UK. A Type 1 diabetes technology pathway: consensus statement for the use of technology in type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2019;36(5):531–8.

Hunt D, Lamb K, Elliott J, Hemmingsen B, Slama S, Scibilia R, et al. A WHO key informant language survey of people with lived experiences of diabetes: media misconceptions, values-based messaging, stigma, framings and communications considerations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;193:110109.

Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):541–51.

Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, et al. Durability of a primary care-led weight-management intervention for remission of type 2 diabetes: 2-year results of the DiRECT open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(5):344–55.

Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, et al. 5-Year follow-up of the randomised Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) of continued support for weight loss maintenance in the UK: an extension study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12(4):233–46.

Thom G, Messow CM, Leslie W, Barnes A, Brosnahan N, McCombie L, et al. Predictors of type 2 diabetes remission in the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT). Diabet Med. 2021;38(8):e14395.

He J, Wang Y, Liu Y, Chen X, Bai J. Experiences of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of qualitative evidence protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034126.

Morrison MK, Lowe JM, Collins CE. Australian women’s experiences of living with gestational diabetes. Women Birth. 2014;27(1):52–7.

Rose MK, Costabile KA, Boland SE, Cohen RW, Persky S. Diabetes causal attributions among affected and unaffected individuals. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2019;7(1):e000708.

Persky S, Costabile KA, Telaak SH. Diabetes causal attributions: pathways to stigma and health. Stigma Health. 2021;2021:896.

Hildebrandt T, Bode L, Ng JS. Effect of ‘lifestyle stigma’on public support for NHS-provisioned pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and preventative interventions for HPV and type 2 diabetes: a nationwide UK survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e029747.

Speight J, Holmes-Truscott E, Garza M, Scibilia R, Wagner S, Kato A, et al. Bringing an end to diabetes stigma and discrimination: an international consensus statement on evidence and recommendations. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol. 2024;12(1):61–82.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Publication and dissemination of research: a guide supporting the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research. 2020. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-code-responsible-conduct-research-2018#download. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Diabetes Australia. Diabetes Australia strategic plan 2020-25. 2020. https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Strategic-Plan-2020-25.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2023.

Holmes-Truscott E, Holloway EE, Lam B, Baptista S, Furler J, Hagger V, et al. ‘Is Insulin Right for Me?’: web-based intervention to reduce psychological barriers to insulin therapy among adults with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2023;40(7):e15117.

The James Lind Alliance. The James Lind Alliance guidebook. 2021. www.jla.nihr.ac.uk. Accessed 14 Dec 2023.

Acknowledgements

We thank the people with diabetes and family members who participated in the consultation. We thank the Steering Group for their input in the project. Participants were recruited via the National Diabetes Services Scheme. The National Diabetes Services Scheme is an initiative of the Australian Government administered by Diabetes Australia.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was funded by a General Grant awarded by the Diabetes Australia Research Program (DARP). Christel Hendrieckx, Elizabeth Holmes-Truscott and Jane Speight are supported by the core funding to the Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes provided by the collaboration between Diabetes Victoria and Deakin University.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Christel Hendrieckx, Sienna Russell-Green, Timothy Skinner, Ashley H. Ng, Chris Lee, Siobhan Barlow, Alan Davey, Caitlin Rogers, Elizabeth Holmes-Truscott and Jane Speight have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

This research study received ethics approval from the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2021-268).

Consent to Participate and Consent for Publication

All study participants provided informed consent prior to taking part, including consent for de-identified study findings to be published.

Availability of Data and Material and Code Availability

Supplementary files detail all research topics and themes generated with example quotes. Further de-identified data may be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Authors’ Contributions

CH, JS, EHT and TK contributed to the study conception and design. CH, EHT, SRG, SB, AD and CR developed the survey questions, SRG collected the data and performed data cleaning and analysis with support from CH and EHT. All authors discussed the findings at each step of the iterative project, which informed the next step of the iterative process. The first draft and subsequent revisions of the paper were written by CH and EHT, all authors commented on the draft versions of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hendrieckx, C., Russell-Green, S., Skinner, T. et al. Diabetes Research Matters: A Three-Round Priority-Setting Survey Consultation with Adults Living with Diabetes and Family Members in Australia. Patient 17, 441–455 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-024-00688-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-024-00688-5