Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of sociodemographic characteristics and illness experience on time trade-off (TTO)-based utility scores using data from the EQ-5D-5L Egyptian valuation study.

Methods

Data were from the Egyptian valuation study that was conducted using the adapted translated version of the EQ-VT to develop the Egyptian Tariff for the EQ-5D-5L based on preferences of the Egyptian population. Data were analysed using a series of univariate and multivariable censored linear regression models adjusted for severity of health states where the dependent variable was the TTO scores and the independent variables included age, sex, education, geographical region, dwelling, marital status, number of people in the household, employment status, having health insurance, number of chronic conditions, previous experience with illness, and self-rated health.

Results

Age, sex, education, marital status, dwelling, region of residence, health insurance and multimorbidity were significantly associated with health state valuations, while employment status, number of people in a household, religion, and previous experience with illness had non-significant associations.

Conclusion

Age, sex and marital status are the main determinants of health state valuation in the Egyptian population, a finding consistent with those from other countries. Knowing these factors will help tailor health services provided and improve patient-centered care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Exploring the main determinants of health state valuation is recommended to identify the sociodemographic characteristics that have the most significant effect on the preferences of the society. |

Relevant information about the influence of demographic characteristics enables public policy and decision makers to consider how health policy and treatment guidelines may differentially influence the population they serve. |

Identifying the health preferences between population groups and geographical regions are important for decision makers to make efficient and fair decisions and promote health equity. |

1 Introduction

Cost-utility analysis (CUA) is a variant of cost-effectiveness analysis that is increasingly used in health technology assessments to support and inform health policy decision making [1]. In CUA, the benefits are measured in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) that combine both quality and quantity of life into a single number [2]. Generic preference-based measures such as the EQ-5D, the Health Utilities Index (HUI) and the Short Form 6-Dimensions (SF-6D) are designed for measuring and valuing health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and calculating QALYs [3,4,5]. These measures include a descriptive system comprised of several dimensions used to describe an individual’s health state, along with a set of values for each health state described by this descriptive system. These values, often referred to as utility values, can be derived from a sample that represents the general public using preference elicitation methods such as standard gamble (SG), time trade-off (TTO) and discrete choice experiments (DCE) [6, 7]. The EQ-5D is the most widely used multiattribute generic preference-based measure [3, 8]. The EuroQol group has developed a standard valuation protocol for the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire (EQ-VT) that involves using two preference elicitation techniques (composite TTO [cTTO] and DCE) in EQ-5D valuation studies [9]. The TTO valuation task is considered to be cognitively challenging and is reportedly associated with comprehension difficulties as well as emotional stress [10].

An individual’s sociodemographic characteristics may influence their valuation and utility scores during TTO exercises. Age [11,12,13,14,15,16,17], sex [11, 13, 15], race [11, 18], illness experience [19,20,21,22,23,24], education level [12], religious beliefs [14, 25], marital status and being a parent or caregiver [13, 15, 26] are among the determinants that have been found to influence health state valuation. More specifically, people of older age [11, 12, 15,16,17, 27] and female sex [11, 13, 27] were significantly associated with lower TTO scores, while those who believe in the afterlife [14, 25] and married individuals (especially with children) [13, 15] focus on longevity rather than quality of life. However, research examining the impact of education, occupation, social class and geographical region on preferences is limited. Evidence on the impact of previous illness experience and chronic conditions on health state valuations is mixed, whereby some studies reported significant differences between patients and the general population [21, 22], while others found trivial [20, 24] or no effect [23]. To our knowledge, determinants of TTO valuations for the EQ-5D-5L hypothetical health states were explored in two previous EQ-5D-5L valuation studies [27, 28].

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of sociodemographic characteristics and illness experience on TTO-based utility scores using data from the EQ-5D-5L Egyptian valuation study [29]. The increased awareness and interest in pharmacoeconomics in Egypt among decision makers and academics make this study well timed and essential. Furthermore, identifying the most influential sociodemographic characteristics may aid in improving the design of the future valuation studies and provide important insights for decision making in the health care system.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

Data were obtained from the Egyptian valuation study that was conducted by trained interviewers using the adapted translated version of the EQ-VT to develop the Egyptian Tariff for the EQ-5D-5L based on the general preferences of the Egyptian population [29]. Participants were recruited through personal contact or from public places using multistratified quota sampling based on Egyptian official statistics updated in March 2019 [30], to select a representative sample in terms of age, sex, and geographical distribution. Participants completed two preference elicitation techniques (cTTO and DCE), in addition to a country-specific questionnaire in which participants were asked about their sociodemographic characteristics, current illness, conflicts of the valuation tasks with their religious beliefs, and beliefs about life and death. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2 Dependent Variable: EQ-5D-5L Health States Valuation

The EQ-5D-5L describes five dimensions of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has five levels of severity: ‘no’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, ‘severe’ and ‘unable/extreme’ [31, 32]. The combination of the five dimensions and their levels results in a health state. Each health state can be described by a five-digit number that ranges from 11111 (no problems in any of the five dimensions) to 55555 (extreme problems or unable to in all dimensions). The EQ-VT design elicits preferences using cTTO and DCE. The cTTO design consists of a set of 86 hypothetical health states assigned to 10 blocks, where each block includes the worst possible health state (55555), one very mild health state (21111, 12111, 11211, 11121, 11112), and eight unique health states [9, 33]. A block including 10 hypothetical health states is randomly assigned to each participant.

cTTO consists of the conventional TTO for those health states better than dead and the lead time TTO (LT-TTO) for those states considered worse than being dead [34]. In the traditional TTO, participants are asked to choose between living 10 years in full health and living 10 years in an impaired health state. Based on the response to this first question, the number of years in full health are varied according to a predefined iteration procedure until the respondent is indifferent between the two options [34]. If the respondent decides that he/she would rather die than live 10 years in the impaired health state, the LT-TTO task starts. In the LT-TTO, the participant is asked to choose between living 10 years in full health then death and 10 years in full health followed by 10 years in the same impaired health state then death [35]. Raw cTTO scores range between 1 and − 1 and were considered the dependent variable in this analysis.

2.3 Independent Variables

Sociodemographic data were collected for each participant, such as age, sex, educational level (illiterate, below intermediate [below high school level], intermediate [high school level or 2 years institute], university degree and above), geographical region (Greater Cairo, Alexandria, Delta, Suez Canal, North Upper Egypt, Asyut, South Upper Egypt), dwelling (urban, rural), religion (Muslim, Christian), marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed), number of people in the household (children and adults), employment status (employed, unemployed/retired/student/housewife), having health insurance (yes [full, partial], no), number of the self-reported chronic conditions, which included cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, renal, endocrine, and blood disorders in addition to bone, blood, eye, mood or anxiety disorders and cancer. Additionally, participants were asked about their general preferences for quality or quantity of life and three questions on experiencing serious illness in themselves, their family members or when caring for others. A positive response on any of the three questions was considered a previous illness experience. Participants also described their own health using the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system and the visual analogue scale (VAS).

2.4 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the sample characteristics were computed. The association between each of the independent variables and TTO scores was examined using a series of univariate censored linear regression models adjusted for severity of health states. A multivariable censored linear regression model adjusted for severity of health states was then fitted with TTO values as the dependent variable and included all the independent variables examined in univariate analysis. Severity of health states was adjusted for by including five dimension-specific ordinal variables with five levels each to describe the health state vector [27]. We tested interactions of age and sex with the number of comorbidities and preference for quality versus quantity of life; none of the interactions were significant and therefore were not included in the final model. Given the strong association between preference for quality and quantity of life with the TTO scores, we examined the final model without including this variable; however, the results remained the same and as such the variable was retained in the final model. All statistical analyses and data management were performed using the STATA 15.0 package (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). The intreg command specifying that the outcome is point data not interval data was used. This command does not compute R2 or pseudo-R2, therefore we computed an approximate measure of fit by calculating the R2 between the predicted and observed values.

3 Results

3.1 General Characteristics of Respondents

The average age of respondents (N = 972) was 36.9 years (standard deviation [SD] 12.7), 47.7% were female, 61.9% were married, 59% completed high school education or more, and 75.2% were employed (Table 1). The majority of participants (67.7%) lived in urban areas, with a representative distribution across geographical areas in the country. The vast majority of respondents (95.8%) were Muslim, 59.6% reported having full or partial health insurance, and 75.6% had four or more people living in one household. The average number of chronic conditions was 0.4 (SD 0.7), with only 8.2% reporting having two or more comorbid chronic conditions. The majority of respondents (69.7%) reported having a previous experience with illness in themselves or in others, 80.2% had a preference for quality over quantity of life, and 95% and 88.7% of participants stated that the valuation tasks did not cause any conflicts with their religious beliefs or influenced their TTO responses, respectively.

Almost one-third of respondents (31.8%) reported mild–extreme (levels 2–5) problems in mobility, 6.4% in self-care, 31.5% in usual activities, 60.5% in pain/discomfort and 64.2% in anxiety/depression, and 15.2% of participants were in a health state (11111). The mean VAS score (EQ-VAS) in this sample was 77.0 (SD 16.7); 58.5% had an EQ-VAS score of 80–100 (Table 1).

3.2 Determinants of Time Trade-Off Scores of Health States

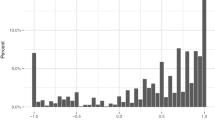

In univariate analyses adjusted for severity of health states, those aged 31–45 years, older adults (over 60 years of age) and females had lower TTO scores for valued health states compared with young-age adults (18–30 years) and males, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 1). Divorced/widowed respondents had lower TTO values than single respondents. Literate respondents of any educational level provided higher TTO scores for valued health states compared with illiterate respondents (Fig. 2). Respondents from Alexandria and North Upper Egypt had lower values than those from Greater Cairo, and those with any kind of health insurance had lower values than those without. Compared with those with no comorbid conditions, respondents with two or more comorbidities had lower TTO scores for valued health states. Finally, respondents who indicated a preference for quantity over quality of life had higher TTO scores for the valued health states. Employment status, dwelling, number of people in a household, religion, and previous experience with illness were not significantly associated with health state valuations.

In the adjusted multivariable censored linear regression model (R2 = 54%), age, sex, marital status, educational level, dwelling, region of residence, number of comorbidities, health insurance and preference for quantity of life were significantly associated with health state valuations (Table 2). Employment status, number of people in a household, religion and previous experience with illness were not significantly associated with health state valuations in the final model.

4 Discussion

This study examined sociodemographic characteristics on TTO-based health state preferences for the EQ-5D-5L using data from the Egyptian valuation study [29]. Age, sex, education, marital status dwelling, region of residence, health insurance, multimorbidity and preference for quantity of life were significantly associated with health state valuations, while employment status, number of people in a household, religion, and previous experience with illness had a non-significant association using a series of univariate and multivariable censored linear regression models adjusted for severity of health states. The overall fit of the model as shown by R2 was 54%, which is higher compared with previous studies [16,17,18].

The study findings showed that older age > 60 years and those aged 31–45 years were associated with significantly lower TTO scores for valued health states compared with young age (18–30 years). Previous studies have found that age is of one of the main characteristics significantly associated with TTO scores. Our findings are consistent with those in previous studies that found older respondents are more likely to trade more life-years [11, 12, 15,16,17, 27], but are contradictory to the findings of Santos et al. and Jakubczyk, who reported that older age was associated with higher utility values [14, 36]. The significant effect of older age on lower TTO scores could be partly explained by the lower subjective life expectancy (SLE) expected by older adults [12, 17]. For participants who did not believe that they actually had 10 more predicted years to live, it might be expected to trade the excess life-years where the relevant ages are not normally reached within the 10-year time frame [15, 37]. Additionally, those participants might be willing to give up life-years in order not to burden loved ones and are more concerned about helplessness and dependency [15, 16]. This is in line with the responses of this age category (>60 years) for the country-specific questions that were specially designed for the Egyptian valuation study, whereby 44.4% stated that their major concern for serious illness is being a burden on family and friends. Moreover, the effect of age is unequal across different health states, being more obvious for moderate and severe health states than for mild health states, suggesting that the time preference of health is dependent on the severity of health states [37].

Female respondents have lower TTO utility scores compared with males, which is also consistent with previous literature, where sex was found to be significantly associated with TTO responses [11, 13, 27]. Dolan et al. reported that women may be more concerned about the burden they would be on others than men as they have experience of caring for those with serious illness [37]. Additionally, in the Arab and Islamic world, women have more concern about the consequences of serious illness and being a burden on others due to their multiple social and economic roles that cannot be neglected, such as maternal, matrimonial duties, and providing care for elderly parents or other relatives in addition to participation in the labour force [38].

In this study, married participants had higher TTO valuations, which is consistent with previous literature. This might be attributed to the notion that married participants, especially those with children, consider the consequences of their choices on others where they focus on longevity rather than quality of life due to their insatiable needs for living long enough with their families and for their children [13, 15]. Moreover, in this study, widowed and divorced participants had lower TTO valuations, which might be due to the fact that 85.7% of them were females and might have some depression symptoms and greater economic vulnerability, in addition to the social stigma attached to divorce in Egypt [39, 40]

In this study, illiterate participants provided lower utility scores than literate participants. This is in contradiction to two previous studies that reported that participants with less education were not willing to trade life-years [12, 37]. Dolan et al. suggested that less-educated participants might be more likely to suffer from ‘status quo effect’ or they may simply be less willing to trade life-years due to limited numeracy [37]. In the Chinese EQ-5D-5L Valuation study, participants with higher education were more likely to be non-traders and have higher TTO values [28], while in the EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Canada, educational level was not significantly associated with health state valuations [27]. In the Moroccan EQ-5D-3L valuation study, mean TTO scores of health states valued by illiterate respondents were slightly higher than that of literates, however the difference was not statistically significant, where graphical representations were created for all the TTO and DCE health states included in the design and printed in a booklet [41]. In the Egyptian valuation study, a novel tool was used for the illiterate and less-educated participants that included pictorial representation of the EQ-5D-5L health states using graphics to describe the five dimensions and coloured cards to represent the five levels of severity, which aided in imagining the EQ-5D-5L hypothetical health states with different levels of severity [29, 42]. To our knowledge, no previous research explored the influence of illiteracy on TTO valuations in the EQ-5D-5L valuation studies. Future research is needed to clarify the impact of illiteracy on TTO valuations where it is not known whether the graphical representation of the health states is responsible for such difference in obtaining values between literate and illiterate participants.

Health care system inequities in Egypt demonstrate that upper Egypt is the most disadvantaged area while urban governorates are the most advantaged governorates in terms of facilities, human resources and financing [43], which is in line with our findings that participants from Upper Egypt had lower TTO values than those from Greater Cairo and in contrast to the other findings that participants in Alexandria and those living in urban areas had lower TTO values compared with Greater Cairo and rural areas, respectively.

In this study, the presence of multimorbidity (two or more comorbidities) was associated with significantly lower utility scores, which may be attributed to the diversity in the Egyptian health care system where 59% of Egyptians are covered by the Health Insurance Organizations (HIO), of whom only 6% actually utilise its services because the coverage is unsatisfactory, leading to the increase of out-of-pocket expenses by people seeking healthcare services [44, 45].

Our finding with respect to the impact of chronic conditions is consistent with some studies and contradictory to others [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Krabbe et al. reported higher patient TTO values for almost all the hypothetical health states [21], while Little et al. reported that people with experienced health states gave significantly lower mean tariff scores for most patient groups [22]. Pickard et al. reported a trivial impact of most self-reported chronic conditions on health state valuations, except for cancer patients with additional conditions whose mean scores were significantly lower compared with those with no chronic conditions [20]. Gandhi et al. reported a similar finding, except for heart disease patients, who had higher mean scores compared with those with no chronic conditions [24]. Additionally, two large meta-analyses reported contradictory conclusions, where Dolders et al. demonstrated no significant difference between patients and general population preferences [46], while Peeters and Stiggelbout reported that patients gave higher valuations than members of the general public [47]. Such differences among studies might be explained by the different types and numbers of comorbidities, different approaches used to measure preferences, and different structure and quality of healthcare systems in the countries in which these studies were conducted, which affect people’s perception and preferences during health state valuations [27].

The preferences of the general population as a source of societal values are mostly used by policy makers and health technology assessment agencies to avoid individual bias and subgroup self-interests [48]. However, identifying the main determinants of health state valuations enables researchers to understand how and why valuations differ and promotes the design of future valuation studies with quotas [14], or conducting weighting analysis for the underrepresented quotas in the produced value sets to explore how demographic characteristics influence health state valuations. Exploring the main determinants of health valuations in future valuation studies is recommended using standardised valuation protocols and modelling techniques with strict quality control processes to identify the most influential sociodemographic characteristics that affect the preferences of the society and to facilitate comparison between countries with different preferences and cultures.

Although this study provides important insights on subgroup differences on reported utility values, some limitations are noted. First, we relied on self-reported chronic conditions and we did not have information about the severity and duration of these conditions. Second, other variables have not been explored, such as parenting (having children) and whether participants considered themselves adherent to religious practices on the TTO responses; however, the majority of the respondents stated that the valuation tasks did not cause any conflicts with religious beliefs.

Finally, although Egypt is a Middle Eastern, lower middle-income country, our main finding that health preferences vary by sociodemographic characteristics such as age, sex and marital status are in accordance with previous research that was conducted in Western, higher-income countries [11, 13, 27]. Further research is needed to understand the sources of differences in valuations between different population subgroups, recognising such differences will allow public policy and decision makers to consider how health policy and treatment guidelines may differentially influence the population they serve [11].

5 Conclusion

Our main findings show that age, sex and marital status are the main determinants of health state valuations. Exploring the main determinants of health state valuation are recommended to identify the most influential sociodemographic characteristic that affects the preferences of the society, thus helping resource allocation decisions and reducing health inequities.

References

Bloom BS. Use of formal benefit/cost evaluations in health system decision making. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(5):329–35.

Whitehead SJ, Ali S. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: the QALY and utilities. Br Med Bull. 2010;96(1):5–21.

Brooks R, Group E. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72.

Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, DePauw S, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 system. Med Care. 2002;40(2):113–28.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21(2):271–92.

Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal: a review. J Health Econ. 1986;5(1):1–30.

Bansback N, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Anis A. Using a discrete choice experiment to estimate health state utility values. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):306–18.

Kennedy-Martin M, Slaap B, Herdman M, van Reenen M, Kennedy-Martin T, Greiner W, et al. Which multi-attribute utility instruments are recommended for use in cost-utility analysis? A review of national health technology assessment (HTA) guidelines. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21(8):1245–57.

Oppe M, Devlin NJ, van Hout B, Krabbe PF, de Charro F. A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2014;17(4):445–53.

Lugnér AK, Krabbe PF. An overview of the time trade-off method: concept, foundation, and the evaluation of distorting factors in putting a value on health. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20(4):331–42.

Craig BM, Reeve BB, Cella D, Hays RD, Pickard AS, Revicki DA. Demographic differences in health preferences in the United States. Med Care. 2014;52(4):307.

Van Nooten F, Koolman X, Brouwer W. The influence of subjective life expectancy on health state valuations using a 10 year TTO. Health Econ. 2009;18(5):549–58.

Dolan P, Roberts J. To what extent can we explain time trade-off values from other information about respondents? Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(6):919–29.

Santos M, Monteiro AL, Santos B. Exploring the predictors of health valuations of EQ 5D 3L with a mixed-effects linear model. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20(4):363–7.

Van Nooten F, van Exel N, Koolman X, Brouwer W. “Married with children” the influence of significant others in TTO exercises. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):94.

Dolan P. Effect of age on health state valuations. J Health Serv Res Pol. 2000;5(1):17–21.

Nooten FV, Brouwer W. The influence of subjective expectations about length and quality of life on time trade-off answers. Health Econ. 2004;13(8):819–23.

Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Chen S, Levin JR, Coons SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in preferences for the EQ-5D health states: results from the US valuation study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(5):479–90.

Ubel PA, Loewenstein G, Jepson C. Whose quality of life? A commentary exploring discrepancies between health state evaluations of patients and the general public. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(6):599–607.

Pickard AS, Tawk R, Shaw JW. The effect of chronic conditions on stated preferences for health. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(4):697–702.

Krabbe PF, Tromp N, Ruers TJ, van Riel PL. Are patients’ judgments of health status really different from the general population? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9(1):31.

Little MH, Reitmeir P, Peters A, Leidl R. The impact of differences between patient and general population EQ-5D-3L values on the mean tariff scores of different patient groups. Value Health. 2014;17(4):364–71.

Kind P, Dolan P. The effect of past and present illness experience on the valuations of health states. Med Care. 1995;33(4 Suppl):255–63.

Gandhi M, Thumboo J, Luo N, Wee H-L, Cheung Y-B. Do chronic disease patients value generic health states differently from individuals with no chronic disease? A case of a multicultural Asian population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):1–9.

Jakubczyk M, Golicki D, Niewada M. The impact of a belief in life after death on health-state preferences: true difference or artifact? Qual Life Res. 2016;25(12):2997–3008.

Matza LS, Boye KS, Feeny DH, Johnston JA, Bowman L, Jordan JB. Impact of caregiver and parenting status on time trade-off and standard gamble utility scores for health state descriptions. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):48.

Al Sayah F, Bansback N, Bryan S, Ohinmaa A, Poissant L, Pullenayegum E, et al. Determinants of time trade-off valuations for EQ-5D-5L health states: data from the Canadian EQ-5D-5L valuation study. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(7):1679–85.

Jin X, Liu GG, Luo N, Li H, Guan H, Xie F. Is bad living better than good death? Impact of demographic and cultural factors on health state preference. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(4):979–86.

Al Shabasy S, Abbassi M, Finch A, Roudijk B, Baines D, Farid S. The EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Egypt. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-021-01100-y.

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics—CAPMAS. 2019. http://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/StaticPages.aspx?page_id=5035. Accessed 9 May 2019.

Brauer CA, Rosen AB, Greenberg D, Neumann PJ. Trends in the measurement of health utilities in published cost-utility analyses. Value Health. 2006;9(4):213–8.

Rabin R, Charro FD. EQ-SD: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–43.

Oppe M, Van Hout B. The “power” of eliciting EQ-5D-5L values: the experimental design of the EQ-VT. EuroQol Working Paper Series. 2017: 17003. http://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/EuroQol-Working-Paper-Series-Manuscript-17003-Mark-Oppe.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Oppe M, Rand-Hendriksen K, Shah K, Ramos-Goñi JM, Luo N. EuroQol protocols for time trade-off valuation of health outcomes. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(10):993–1004.

Devlin NJ, Tsuchiya A, Buckingham K, Tilling C. A uniform time trade off method for states better and worse than dead: feasibility study of the ‘lead time’approach. Health Econ. 2011;20(3):348–61.

Jakubczyk M. Impact of complementarity and heterogeneity on health related utility of life. Cent Eur J Econ Model Econ. 2009;1:139–56.

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ. 1996;5(2):141–54.

Hussein S (ed). The role of women in long-term care provision: perspectives on aging in the Arab and Islamic World. In: 10th Islamic countries conference on statistical sciences (ICCS-X) Proceedings, The Islamic Countries Society of Statistical Science; 2010.

Kasemy ZA, Salama AA, Abo Salem ME, Negm N. Factors related to depression symptoms among working women in Menoufia, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2016;91(4):163–8.

Sieverding M, Hassan R, editors. Associations between economic vulnerability and health and wellbeing in Egypt; working paper No.1364, Giza: The Economic Research Forum (ERF); 2019.

Al Sayah F, Kooli A, Rouahi Y, Allou Y, Zarrik H, Abouqal R, et al. PNS324 A novel approach of using graphical representation of EQ-5D-3L dimensions, levels, and health states for illiterate respondents in valuation studies—an example from Morocco. Value Health. 2019;22:S819.

Al Shabasy S, Abbassi M, Farid S. EQ-VT protocol: one-size-fits-all? Challenges and innovative adaptations used in Egypt: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021;11(12):e051727. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051727.

Zaky HH, Abdel-Mowla SAA. Health outcome inequities and the health system: a case study of Egypt. Res World Econ. 2011;2(2):71.

National Health Accounts (NHA) 2008/2009 report. https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Egypt-National-Health-Accounts-2008_09.pdf. Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

.Health Insurance Organization (HIO). http://www.hio.gov.eg/Ar/covers/Pages/Charts4.aspx. Accessed 16 Feb 2021.

Dolders MG, Zeegers MP, Groot W, Ament A. A meta-analysis demonstrates no significant differences between patient and population preferences. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(7):653–64.

Peeters Y, Stiggelbout AM. Health state valuations of patients and the general public analytically compared: a meta-analytical comparison of patient and population health state utilities. Value Health. 2010;13(2):306–9.

Ubel PA, Richardson J, Menzel P. Societal value, the person trade-off, and the dilemma of whose values to measure for cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2000;9(2):127–36.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the EuroQol support team, the interviewers and the study participants for taking part in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This project received financial support from Bournemouth University and the EuroQol Foundation, The Netherlands (project ID: 20180130). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing, writing and publishing the study results.

Conflict of interest

Sahar Al Shabasy, Fatima Al Sayah, Maggie Abbassi, and Samar Farid declare they have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the contents of this article.

Ethics approval

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Participants were informed about their freedom of refusal. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the research process.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Sahar Al Shabasy participated in the study planning and data collection, performed data quality control reports and interpretation of the results, and prepared the draft manuscript. Fatima Al Sayah participated in the follow up of the data collection, the quality control process, statistical analysis and interpretation of the study results, and reviewed the final manuscript. Maggie Abbassi and Samar Farid participated in the study preparation, proof reading of the translated version, follow up of the data collection, quality control process and interpretation of the results, and reviewed the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Shabasy, S., Al Sayah, F., Abbassi, M. et al. Determinants of Health Preferences Using Data from the Egyptian EQ-5D-5L Valuation Study. Patient 15, 589–598 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-022-00572-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-022-00572-0