Abstract

Background and Objective

Patients can express preferences for different treatment options in a healthcare context, and these can be measured with quantitative preference elicitation methods.

Objective

Our objective was to conduct a scoping review to determine how preference elicitation methods have been used in the design of clinical trials.

Methods

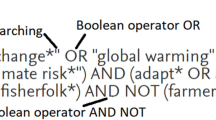

We conducted a scoping review to identify primary research studies, involving any health condition, that used quantitative preference elicitation methods, including direct utility-based approaches, and stated preference studies, to value health trade-offs in the context of clinical trial design. Studies were identified by screening existing systematic and scoping reviews and with a primary literature search in MEDLINE from 2010 to the present. We extracted study characteristics and the application of preference elicitation methods to clinical trial design according to the SPIRIT checklist from primary studies and summarized the findings descriptively.

Results

We identified 18 eligible studies. The included studies applied patient preferences to five areas of clinical trial design: intervention selection (n = 1), designing N-of-1 trials (n = 1), outcome selection and weighting composite and ordinal outcomes (n = 12), sample size calculations (n = 2), and recruitment (n = 2). Using preference elicitation methods led to different decisions being made, such as using preference-weighted composite outcomes instead of equally weighted composite outcomes.

Conclusion

Preference elicitation methods are infrequently used to design clinical trials but may lead to changes throughout the trial that could affect the evidence generated. Future work should consider measurement challenges and explore stakeholder perceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US National Library of Medicine. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Patient Preference MeSH Descriptor Data. 2021. https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/record/ui?ui=D057240. Accessed Apr 2021.

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2(1):55–64.

O’Brien B, Elswood J, Calin A. Willingness to accept risk in the treatment of rheumatic disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1990;44(3):249–52.

Durand C, Eldoma M, Marshall DA, Bansback N, Hazlewood GS. Patient preferences for disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(2):176–87.

Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health–a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;16(1):3–13.

European Medicines Agency (EMEA). Benefit-Risk methodology project: Work package 2 report: Applicability of current tools and processes for regulatory benefit-risk assessment. 2011. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/benefit-risk-methodology-project-work-package-2-report-applicability-current-tools-processes_en.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patient Preference Information - Voluntary Submission, Review in Premarket Approval Applications, Humanitarian Device Exemption Applications, and De Novo Requests, and Inclusion in Decision Summaries and Device Labeling. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/92593/download. Accessed Mar 2021.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Johannesson M, Jönsson B, Karlsson G. Outcome measurement in economic evaluation. Health Econ. 1996;5(4):279–96.

Mühlbacher AC, Kaczynski A, Zweifel P, Johnson FR. Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling: an overview. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):2.

Kowalski CJ, Mrdjenovich AJ. Patient preference clinical trials: why and when they will sometimes be preferred. Perspect Biol Med. 2013;56(1):18–35.

Muñoz-Velandia O, Guyatt G, Devji T, Zhang Y, Li S-A, Alexander PE, et al. Patient values and preferences regarding continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and artificial pancreas in adults with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative data. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(4):183–200.

Goshua A, Craigie S, Guyatt GH, Agarwal A, Li R, Bhullar JS, et al. Patient values and preferences regarding opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2018;19(12):2469–80.

Tong BC, Huber JC, Ascheim DD, Puskas JD, Ferguson TBJ, Blackstone EH, et al. Weighting composite endpoints in clinical trials: essential evidence for the heart team. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(6):1908–13.

Fraenkel L, Wei Z, Ramsey C, Wiedmeyer C, Michaud K, Neogi T, et al. OPEX: Development of a novel overall patient experience measure to facilitate interpretation of comparison effectiveness studies. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0245598.

Metcalfe RK, Harrison M, Hutfield A, Lewisch M, Singer J, Magee LA, et al. Patient preferences and decisional needs when choosing a treatment approach for pregnancy hypertension: a stated preference study. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(5):775–9.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726–32.

Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Dickersin K, Moher D. SPIRIT 2013: new guidance for content of clinical trial protocols. The Lancet. 2013;381(9861):91–2.

Morgan H, Hoddinott P, Thomson G, Crossland N, Farrar S, Yi D, et al. Benefits of Incentives for Breastfeeding and Smoking cessation in pregnancy (BIBS): a mixed-methods study to inform trial design. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(30). http://journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta19300. Accessed Dec 2020.

Cheung YK, Wood D, Zhang K, Ridenour TA, Derby L, St Onge T, et al. Personal preferences for Personalised Trials among patients with chronic diseases: an empirical Bayesian analysis of a conjoint survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e036056.

Herzog TJ, Armstrong DK, Brady MF, Coleman RL, Einstein MH, Monk BJ, et al. Ovarian cancer clinical trial endpoints: Society of Gynecologic Oncology white paper. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(1):8–17.

Stamuli E, Torgerson D, Northgraves M, Ronaldson S, Cherry L. Identifying the primary outcome for a randomised controlled trial in rheumatoid arthritis: the role of a discrete choice experiment. J Foot Ankle Res. 2017;10(101471610):57.

Ahmad Y, Nijjer S, Cook CM, El-Harasis M, Graby J, Petraco R, et al. A new method of applying randomised control study data to the individual patient: A novel quantitative patient-centred approach to interpreting composite end points. Int J Cardiol. 2015;195(gqw, 8200291):216–24.

Butler EL, Laber EB, Davis SM, Kosorok MR. Incorporating patient preferences into estimation of optimal individualized treatment rules. Biometrics. 2018;74(1):18–26.

Haac BE, O’Hara NN, Manson TT, Slobogean GP, Castillo RC, O’Toole RV, et al. Aspirin versus low-molecular-weight heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in orthopaedic trauma patients: A patient-centered randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0235628.

Stafinski T, Menon D, Nardelli A, Bakal J, Ezekowitz J, Tymchak W, et al. Incorporating patient preferences into clinical trial design: results of the opinions of patients on treatment implications of new studies (OPTIONS) project. Am Heart J. 2015;169(1):122-31.e22.

Stolker JM, Spertus JA, Cohen DJ, Jones PG, Jain KK, Bamberger E, et al. Rethinking composite end points in clinical trials: insights from patients and trialists. Circulation. 2014;130(15):1254–61.

Vaanholt MCW, Kok MM, von Birgelen C, Weernink MGM, van Til JA. Are component endpoints equal? A preference study into the practice of composite endpoints in clinical trials. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2018;21(6):1046–55.

Chaisinanunkul N, Adeoye O, Lewis RJ, Grotta JC, Broderick J, Jovin TG, et al. Adopting a patient-centered approach to primary outcome analysis of acute stroke trials using a utility-weighted modified rankin scale. Stroke. 2015;46(8):2238–43.

Franco MR, Howard K, Sherrington C, Rose J, Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML. Smallest worthwhile effect of exercise programs to prevent falls among older people: estimates from benefit–harm trade-off and discrete choice methods. Age Ageing. 2016;45(6):806–12.

Chaudhuri SE, Ho MP, Irony T, Sheldon M, Lo AW. Patient-centered clinical trials. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(2):395–401.

Kerman HM, Deshpande BR, Selzer F, Losina E, Katz JN. Willingness of older adults to participate in a randomized trial of conservative therapies for knee pain: a prospective preference assessment. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2018;9(101671157):93–7.

Smith SM, Gewandter JS, Kitt RA, Markman JD, Vaughan JA, Cowan P, et al. Participant preferences for pharmacologic chronic pain treatment trial characteristics: an ACTTION Adaptive Choice-Based Conjoint Study. J Pain Off J Am Pain Soc. 2016;17(11):1198–206.

Ferreira ML, Herbert RD, Ferreira PH, Latimer J, Ostelo RW, Nascimento DP, et al. A critical review of methods used to determine the smallest worthwhile effect of interventions for low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):253–61.

Hazlewood GS. Measuring patient preferences: an overview of methods with a focus on discrete choice experiments. Rheum Clin North Am. 2018;44(2):337–47.

Finger ME, Boonen A, Woodworth TG, Escorpizo R, Christensen R, Nielsen SM, et al. An OMERACT initiative toward consensus to identify and characterize candidate contextual factors: report from the contextual factors working group. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(11):1734.

Say RE, Thomson R. The importance of patient preferences in treatment decisions–challenges for doctors. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):542–5.

Thorne SE, Paterson BL. Health care professional support for self-care management in chronic illness: insights from diabetes research. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;42(1):81–90.

Patrick-Lake B. Patient engagement in clinical trials: the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative’s leadership from theory to practical implementation. Clin Trials Lond Engl. 2018;15(1_suppl):19–22.

Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, Fayish L, Davidson L, Hickam DH, et al. Patient engagement in research: early findings from the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(3):359–67.

Gooberman-Hill R. Qualitative approaches to understanding patient preferences. The patient. 2012;5(4):215–23.

Nair K, Willison D, Holbrook A, Keshavjee K. Patients’ consent preferences regarding the use of their health information for research purposes: a qualitative study. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(1):22–7.

Ho MP, Gonzalez JM, Lerner HP, Neuland CY, Whang JM, McMurry-Heath M, et al. Incorporating patient-preference evidence into regulatory decision making. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(10):2984–93.

van Overbeeke E, Janssens R, Whichello C, Schölin Bywall K, Sharpe J, Nikolenko N, et al. Design, conduct, and use of patient preference studies in the medical product life cycle: a multi-method study. Front Pharmacol. 2019;3(10):1395–1395.

Whichello C, Bywall KS, Mauer J, Stephen W, Cleemput I, Pinto CA, et al. An overview of critical decision-points in the medical product lifecycle: Where to include patient preference information in the decision-making process? Health Policy Amst Neth. 2020;124(12):1325–32.

Falahee M, Simons G, DiSantostefano RL, Valor Méndez L, Radawski C, Englbrecht M, et al. Treatment preferences for preventive interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: protocol of a mixed methods case study for the Innovative Medicines Initiative PREFER project. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e045851.

Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L. OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8(1):38.

Thomas M, Fraenkel L, Boonen A, Bansback N, Buchbinder R, Marshall D, et al. Patient preferences to value health outcomes in rheumatology clinical trials: Report from the OMERACT special interest group(✰). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51(4):919–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2021.05.008

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [FRN 156267].

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Glen Hazlewood is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award. Dr. Deborah Marshall is supported by the Arthur J.E. Child Chair in Rheumatology Research. Megan Thomas, Dr. Daksh Choudhary, Dr. Susan J. Bartlett, and Dr. Adalberto Loyola Sanchez have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

MT and GS planned and conducted the study; MT and DC collected the data; MT, GS, and DM interpreted the data; and all authors drafted the manuscript and approved the final draft submitted. Megan Thomas is the guarantor of the article.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, M., Marshall, D.A., Choudhary, D. et al. The Application of Preference Elicitation Methods in Clinical Trial Design to Quantify Trade-Offs: A Scoping Review. Patient 15, 423–434 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00560-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00560-w