Abstract

Objective

Choice experiments are increasingly used to obtain patient preference information for regulatory benefit–risk assessments. Despite the importance of instrument design, there remains a paucity of literature applying good research principles. We applied a novel framework for instrument development of a choice experiment to measure type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment preferences.

Methods

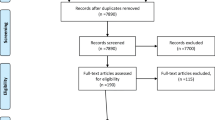

Applying the framework, we used evidence synthesis, expert consultation, stakeholder engagement, pretest interviews, and pilot testing to develop a best–worst scaling (BWS) and discrete choice experiment (DCE). We synthesized attributes from published DCEs for type 2 diabetes, consulted clinical experts, engaged a national advisory board, conducted local cognitive interviews, and pilot tested a national survey.

Results

From published DCEs (n = 17), ten attribute categories were extracted with cost (n = 11) having the highest relative attribute importance (RAI) (range 6–10). Clinical consultation and stakeholder engagement identified six attributes for inclusion. Cognitive pretesting with local diabetes patients (n = 25) ensured comprehension of the choice experiment. Pilot testing with patients from a national sample (n = 50) identified nausea as most important (RAI for DCE: 10 [95 % CI 8.5–11.5]; RAI for BWS: 10 [95 % CI 8.9–11.1]). The developed choice experiment contained five attributes (A1c decrease, blood glucose stability, low blood glucose, nausea, additional medicine, and cost).

Conclusion

The framework for instrument development of a choice experiment included five stages of development and incorporated multiple stakeholder perspectives. Further comparisons of instrument development approaches are needed to identify best practices. To facilitate comparisons, researchers need to be encouraged to publish or discuss their instrument development strategies and findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bridges JF. Stated preference methods in health care evaluation: an emerging methodological paradigm in health economics. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2:213–24.

Weinstein MC, Stason WB. Foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis for health and medical practices. N Engl J Med. 1977. doi:10.1056/NEJM197703312961304.

Section 513(a) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [21 U.S.C. 360c(a)].

Hauber BA, Fairchild AO, Johnson FR. Quantifying benefit-risk preferences for medical interventions: an overview of a growing empirical literature. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013. doi:10.1007/s40258-013-0028-y.

Furlong P, Bridges JFP, Charnas L, Fallon JR, Fischer R, Flanigan KM, Franson TR, Gulati N, McDonald C, Peay H, Sweeney HL. How a patient advocacy group developed the first proposed draft guidance document for industry for submission to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015. doi:10.1186/s13023-015-0281-2.

Romeo GR, Abrahamson MJ. The 2015 standards for diabetes care: maintaining a patient-centered approach. Ann Intern Med. 2015. doi:10.7326/M15-0385

Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. Patient-centered outcomes research institute. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312:1513–1514. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.11100.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Factors to consider when making benefit-risk determinations in medical device pre-market approval and de novo classification. FDA Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. 2012. p. 11–12. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm296379.pdf.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patient preference information—submission, review in PMAs, HDE applications, and de novo requests, and inclusion in device labeling. Draft Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders. 2015. p. 1–11. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm446680.pdf.

Medical Device Innovation Consortium. A Framework for Incorporating Information on Patient Preferences Regarding Benefit and Risk into Regulatory Assessments of New Medical Technology. 2015. p. 126–127. http://mdic.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/MDIC_PCBR_Framework_Web1.pdf.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, Johnson FR, Mauskopf J. Conjoint analysis applications in health—a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013.

Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, Bresnahan BW, Kanninen B, Bridges JF. Constructing Experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223.

Hauber AB, Gonzalez JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn KG, et al. Methods for the statistical analysis of discrete-choice experoments: a report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices task force—draft for review. 2015. p. 1–33. https://ispor.org/TaskForces/ISPOR-Conjoint-Analysis-Statistical-Analysis-GRP-TF-Report_DRAFT-for-REVIEW.pdf.

Marshall D, Bridges JF, Hauber B, Cameron R, Donnalley L, Fyie K, Johnson FR. Conjoint analysis applications in health—how are studies being designed and reported?: an update on current practice in the published literature between 2005 and 2008. Patient. 2010. doi: 10.2165/11539650-000000000-00000

Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD. Stated choice methods: analysis and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, Horrocks SA, Vosper AJ, Swancutt DR, Flynn TN. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012. doi:10.1002/hec.1739.

Wittenberg E, Bharel M, Saada A, Santiago E, Bridges JF, Weinreb L. Measuring the preferences of homeless women for cervical cancer screening interventions: development of a best-worst scaling survey. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0110-z.

Bridges JF, Paly VF, Barker E, Kervitsky D. Identifying the benefits and risks of emerging treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0081-0.

dosReis S, Ng X, Frosch E, Reeves G, Cunningham C, Bridges JF. Using best–worst scaling to measure caregiver preferences for managing their Child’s ADHD: a pilot study. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0098-4.

von Arx LB, Kjeer T. The patient perspective of diabetes care: a systematic review of stated preference research. Patient. 2014. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0057-0.

Joy SM, Little E, Maruthur NM, Purnell TS, Bridges JF. Patient preferences for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a scoping review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013. doi:10.1007/s40273-013-0089-7.

Purnell TS, Joy S, Little E, Bridges JF, Maruthur N. Patient preferences for noninsulin diabetes medications: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2014. doi:10.2337/dc13-2527.

Muhlbacher AC, Kaczynski A. Patients’ preferences in the medicamentous treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2: a systematic classification and meta-comparison of patient preference studies. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015. doi:10.1007/s00103-015-2127-4.

Whitty JA, Lancsar E, Rixon K, Golenko X, Ratcliffe J. A systematic review of stated preference studies reporting public preferences for healthcare priority setting. Patient. 2014. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0063-2.

Wortley S, Wong G, Kieu A, Howard K. Assessing stated preferences for colorectal cancer screening: a critical systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Patient. 2014. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0054-3.

Harrison M, Rigby D, Vass C, Flynn T, Louviere J, Payne K. Risk as an attribute in discrete choice experiments: a systematic review of the literature. Patient. 2014. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0048-1.

Laba TL, Essue B, Kimman M, Jan S. Understanding patient preferences in medication non-adherence: a review of stated preference data. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0099-3.

Peay HL, Hollin I, Fischer R, Bridges JFP. A community-engaged approach to quantifying caregiver preferences for the benefits and risks of emerging therapies for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clinical Therapeutics. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.04.011.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014. doi:10.2337/dc14-S014.

Bennett WL, Maruthur NM, Singh S, Segal JB, Wilson LM, Chatterjee R, Marinopoulos SS, Puhan MA, Ranasinghe P, Block L, Nicholson WK, Hutfless S, Bass EB, Bolen S. Comparative effectiveness and safety of medications for type 2 diabetes: an update including new drugs and 2-drug combinations. Ann Intern Med. 2011. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-201105030-00336.

Bolen S, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson L, Yeh HC, Marinopoulos S, Wiley C, Selvin E, Wilson R, Bass EB, Brancati FL. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and safety of oral medications for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2007. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00178.

Purnell TS, Lynch TJ, Bone L, Segal JB, Evans C, Longo DR, Bridges JF. Perceived barriers and potential strategies to improve self-management among adults with type 2 diabetes: a community-engaged research approach. Patient. 2016. doi:10.1007/s40271-016-0162-3.

PCORI Engagement Rubric. PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) website. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf. Published 4 February 2014. 2015. Accessed 1 April 2016.

Beatty PC, Willis GB. Research synthesis: the practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opin Q. 2007;71. doi:10.1093/poq/nfm006.

Gray E, Eden M, Vass C, McAllister M, Louviere J, Payne K. Valuing preferences for the process and outcomes of clinical genetics services: a pilot study. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0133-0.

GFK. KnowledgePanel Design Summary: KnowledgePanel overview. 2011.

Hollin IL, Peay HL, Bridges JF. Caregiver preferences for emerging duchenne muscular dystrophy treatments: a comparison of best-worst scaling and conjoint analysis. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-014-0104-x.

Aristides M, Weston AR, FitzGerald P, Le Reun C, Maniadakis N. Patient preference and willingness-to-pay for Humalog Mix25 relative to Humulin 30/70: a multicountry application of a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.74007.x.

Bogelund M, Vilsboll T, Faber J, Henriksen JE, Gjesing RP, Lammert M. Patient preferences for diabetes management among people with type 2 diabetes in Denmark—a discrete choice experiment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011. doi:10.1185/03007995.2011.625404.

Jendle J, Torffvit O, Ridderstrale M, Lammert M, Ericsson A, Bogelund M. Willingness to pay for health improvements associated with anti-diabetes treatments for people with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010. doi:10.1185/03007991003657867.

Lloyd A, Nafees B, Barnett AH, Heller S, Ploug UJ, Lammer M, Bogelund M. Willingness to pay for improvements in chronic long-acting insulin therapy in individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.07.017.

Casciano R, Malangone E, Ramachandran A, Gagliardino JJ. A quantitative assessment of patient barriers to insulin. Int J Clin Pract. 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02590.x.

Gelhorn HL, Stringer SM, Brooks A, Thompson C, Monz BU, Boye KS, Hach T, Lund SS, Palencia R. Preferences for medication attributes among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the UK. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013. doi:10.1111/dom.12091.

Guimaraes C, Marra CA, Gill S, et al. A discrete choice experiment evaluation of patients preferences for different risk, benefit, and delivery attributes of insulin therapy for diabetes management. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010. doi:10.2147/PPA.S14217.

Hauber AB, Han S, Yang JC, Gantz I, Tunceli K, Gonzalez JM, Brodovicz K, Alexander CM, Davies M, Iglay K, Zhang Q, Radican L. Effect of pill burden on dosing preferences, willingness to pay, and likely adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013. doi:10.2147/PPA.S43465.

Hauber AB, Johnson FR, Sauriol L, Lescrauwaet B. Risking health to avoid injections: preferences of Canadians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.9.2243.

Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Johnson FR, Falvey H. Treatment preferences and medication adherence of people with Type 2 diabetes using oral glucose-lowering agents. Diabet Med. 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02696.x.

Polster M, Zanutto E, McDonald S, Conner C, Hammer M. A comparison of preferences for two GLP-1 products–liraglutide and exenatide–for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Econ. 2010. doi:10.3111/13696998.2010.529377.

Porzsolt F, Clouth J, Deutschmann M, Hippler HJ. Preferences of diabetes patients and physicians: a feasibility study to identify the key indicators for appraisal of health care values. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-8-125.

Gelhorn HL, Poon JL, Davies EW, Paczkowski R, Curtis SE, Boye KS. Evaluating preferences for profiles of GLP-1 receptor agonists among injection-naive type 2 diabetes patients in the UK. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015. doi:10.2147/PPA.S90842.

Hauber AB, Tunceli K, Yang JC, et al. A survey of patient preferences for oral antihyperglycemic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2015. doi:10.1007/s13300-015-0094-2.

Hauber AB, Nguyen H, Posner J, Kalsekar I, Ruggles J. A discrete-choice experiment to quantify patient preferences for frequency of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist injections in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1117433.

Morillas C, Feliciano R, Catalina PF, Ponte C, Botella M, Rodrigues J, Esmatjes E, Lafita J, Lizán L, Llorente I, Morales C, Navarro-Pérez J, Orozco-Beltran D, Paz S, Ramirez de Arellano A, Cardoso C, Tribaldos Causadias M. Patients’ and physicians’ preferences for type 2 diabetes mellitus treatments in Spain and Portugal: a discrete choice experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015. doi:10.2147/PPA.S88022.

Muhlbacher A, Bethge S. What matters in type 2 diabetes mellitus oral treatment? A discrete choice experiment to evaluate patient preferences. Eur J Health Econ. 2015. doi:10.1007/s10198-015-0750-5.

Peters E, Västfjäll D, Slovic P, Mertz CK, Mazzocco K, Dickert S. Numeracy and decision making. Psychol Sci. 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01720.x.

Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, Moro D, de Bekker-Grob EW. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014. doi:10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Age-adjusted percentage of adults with diabetes using diabetes medication, by type of medication, United States, 1997–2011. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/meduse/fig2.htm

Centers for Disease Control. Mean and median distribution of diabetes duration among adults aged 18–79 years, United States, 1997–2011. 2014.

Kanninen BJ. Optimal design for multinomial choice experiments. J Market Res. 2002. doi:10.1509/jmkr.39.2.214.19080.

Huber J, Zwerina K. The importance of utility balance in efficient choice designs. J Market Res. 1996. doi:10.2307/3152127.

Harun A, Li C, Bridges JF, Agrawal Y. Understanding the experience of age-related vestibular loss in older individuals: a qualitative study. Patient. 2016. doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0156-6.

Longo DR, Crabtree BF, Pellerano MB, et al. A qualitative study of vulnerable patient views of type 2 diabetes consumer reports. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0146-8.

Blome C, von Usslar K, Augustin M. Feasibility of using qualitative interviews to explore patients’ treatment goals: experience from dermatology. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0149-5.

Eiring O, Nylenna M, Nytroen K. Patient-important outcomes in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder: a mixed-methods approach investigating relative preferences and a proposed taxonomy. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0128-x.

Danner M, Vennedey V, Hiligsmann M, Fauser S, Stock S. Focus groups in elderly ophthalmologic patients: setting the stage for quantitative preference elicitation. Patient. 2016. doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0122-3.

Kløjgaard ME, Bech M, Søgaard R. Designing a stated choice experiment: the value of a qualitative process. J Choice Model. 2012. doi:10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70050-2.

Mullard A. Patient-focused drug development programme takes first steps. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013. doi:10.1038/nrd4104.

Ngene. User manual and reference guide. Choice Metrics. 2014.

Fraenkel L, Lim J, Garcia-Tsao G, Reyna V, Monto A, Bridges JF. Variation in treatment priorities for chronic hepatitis C: a latent class analysis. Patient. 2015. doi:10.1007/s40271-015-0147-7.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) Community Research Advisory Council (C-RAC) and members of the Diabetes Action Board (DAB) for their valuable contributions and engagement in the research study. The authors also thank the respondents who participated in the study. Dr. Bridges contributed to the study design and conceptualization, the acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation and is the guarantor of this work. Ms. Janssen contributed to the study design and conceptualization, the acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. Dr. Segal contributed to the acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Methods Award (ME-1303-5946) and by the Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) (1U01FD004977-01). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the data, or preparation of the manuscript. Bridges, Janssen, and Segal have no competing financial or non-financial interests to disclose. This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and, the study protocol was reviewed by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB 6001).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Janssen, E.M., Segal, J.B. & Bridges, J.F.P. A Framework for Instrument Development of a Choice Experiment: An Application to Type 2 Diabetes. Patient 9, 465–479 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0170-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0170-3