Abstract

Background

There is strong evidence of under-reporting of harms in manuscripts on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compared with the volume of raw data retrieved from these trials. Many guidelines have been developed to tackle this, but they have failed to address some important issues that would allow for standardization and transparency. As a consequence, harms reporting in manuscripts remains suboptimal.

Objective

The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) aimed to deliver accurate recommendations for better reporting of harms in clinical trials manuscripts on anti-osteoarthritis (OA) drugs. These could help to better inform clinicians on harms recorded in RCTs and further help researchers conducting meta-analyses.

Methods

Using the outcomes of several systematic reviews on the safety of anti-OA drugs, we summarized the ways in which harms have been reported in OA RCT manuscripts to date. Next, we drafted some recommendations and initiated a modified Delphi process that involved a panel of clinicians and clinical researchers to build an expert consensus on recommendations from the ESCEO for the reporting of harms in future manuscripts on RCTs assessing anti-OA drugs.

Results

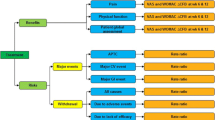

These recommendations emphasize that all treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) should always be taken into account for harms reporting, with no frequency threshold, and describe how specific AEs should be reported; they also provide a list of the most relevant organ systems to be considered according to each class of drug for reporting of harms within the results section of a manuscript. Irrespective of the drug, the ESCEO recommends that total, severe and serious AEs and withdrawals due to AEs should always be reported; guidance on the reporting of specific events pertaining to each category is provided. The ESCEO also recommends the reporting of information on drug effect on biological parameters, with specific guidance.

Conclusions

These recommendations may contribute to improve transparency in the field of safety of anti-OA medications. Pharmaceutical companies developing drugs for OA, and researchers conducting clinical trials, are encouraged to comply with them when reporting harms-related results in manuscripts on RCTs. The ESCEO also encourages journals to refer to the ESCEO recommendations in their instructions to authors for the publication of manuscripts on trials of anti-OA medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

These are the first recommendations for harms reporting in clinical trial manuscripts on drugs specific to osteoarthritis (OA); however, they may also apply to other diseases, particularly for anti-OA drugs that are also used in other fields. |

The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) safety working group emphasizes that all treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) should always be considered for harms reporting, with no frequency threshold; any interpretation of a relationship between an AE and the treatment studied should only be included in the discussion section of the manuscript, when comparing the results with findings from other clinical trials or meta-analyses. |

Clear and specific guidance is provided for the reporting of each type of AE, with particular emphasis that all specific severe and serious events should always be reported; henceforth, information on adverse drug biological effects should also be reported. |

1 Introduction

Drug safety is a critical public health issue but, unfortunately, harms-related data collected from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are not adequately reported in manuscripts [1]. In fact, there is strong evidence of important dissimilarities between published and unpublished adverse event (AE) data from the same study and of published data being systematically under-reported [2,3,4,5]. Many reasons are proposed to explain the practice of under-reporting of AEs, including an emphasis on efficacy rather than harms, a lack of statistical significance, and restrictions on manuscript length [6,7,8,9].

Several initiatives have been undertaken in an attempt to tackle the inadequate reporting of harms in manuscripts on RCTs. These include the development of an extension of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement specifically dedicated to harms reporting [10]. However, this more general guidance, primarily dealing with how AE information should be reported in various sections of the manuscript, fails to provide clear instruction on which “type” of AE should be described in the results section and how to uniformly report harms across studies. Consequently, despite the release of the CONSORT-harms extension statement, practices around reporting of AE results were still found to be inadequate and inconsistent [11,12,13]. Thus, additional recommendations to improve AE reporting in clinical trial publications have been developed to complement the CONSORT-harms extension statement by providing guidance on the reporting of clinically informative harms-related data [14]. These recommendations specify deaths, serious AEs and dropouts due to AEs as the harms that should always be reported, whatever the intervention or the population being studied. However, for the reporting of other AEs, the authors suggest multiple strategies, which include reporting AEs according to clinical relevance, reporting the most common AEs (using a threshold of occurrence), or grouping AEs according to organ systems [14]. While representing progress compared with the CONSORT-harms extension statement, this left the choice of reporting harms-related data to author preference, which might not allow comparability between different trials on the same drug or between various trials on different classes of drugs for the same disease; in addition, combining the results reported using such different reporting systems in a meta-analysis may not prove meaningful.

Further to the release of the CONSORT-harms extension statement in 2004 [10] and prior to the publication of the recommendations by Lineberry et al. [14] in 2016, both of which were rather broad and not disease/drug-specific in nature, two recommendations specific to the reporting of harms with some pain medications were published in 2013 [15, 16]. Interestingly, the authors of these recommendations raised and addressed many of the most important points that should be considered for comprehensive reporting of relevant AEs in manuscripts. However, these recommendations failed to clarify some issues that we consider essential with regard to standardization and transparency in the reporting of AEs. Notably, although not specifically dedicated to the reporting of harms in OA, these guidelines on the reporting of harms for pain medications apparently did not help to improve the reporting of AEs in manuscripts on OA, a disease in which pain is an important outcome [17,18,19]. As an illustration, manuscripts on randomized trials in OA published in 2018 still lack completeness and consistency in the reporting of AEs [20,21,22,23].

While some progress has been made in the reporting of AEs in clinical trial manuscripts in recent years [15, 16], it is still recognized that considerable improvements are needed [24,25,26]. The need for disease-specific guidance on AE reporting has been identified to enable consistency in the disclosure of harms across RCT manuscripts [13] by standardizing the reporting of harms-related results. Such specific guidance does not exist in the field of musculoskeletal diseases, and particularly for OA.

To close this gap, a working group of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO), through publication of this document, aims to complement the existing recommendations on the reporting of clinical trials. The ESCEO recommendations provide specific, clear, practical and standardized guidance on the reporting of harms in manuscripts on RCTs assessing anti-OA drugs. These recommendations are limited to manuscripts for publication of RCTs in scientific journals; therefore, sponsors of clinical trials should continue to adhere to regulatory guidelines for reporting AEs arising from clinical trials to regulatory authorities worldwide [27,28,29].

2 Methods

Recently, the ESCEO commissioned several systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials to reassess the safety of various anti-OA medications, including topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), symptomatic slow-acting drugs for OA (SYSADOAs) and intra-articular hyaluronic acid (IAHA) [30,31,32]. For this purpose, the MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Scopus databases were comprehensively searched. The methodology and the outcomes of these systematic reviews have been extensively described in each manuscript. From the articles included in each systematic review, we collected information on how AE data were reported; details on how AE-related results were reported in each article retrieved from the systematic review processes can be found in the tables describing the characteristics of the included studies in each specific manuscript reporting the outcomes of these new meta-analyses (in this supplement) [30,31,32]. For the purpose of preparing the ESCEO recommendations for the reporting of harms in future manuscripts on trials on anti-OA medications, we summarized the ways in which harms-related data have been reported across the articles retrieved for these new ESCEO meta-analyses, and report here the common sub-standard harms reporting practices found in these prior manuscripts on RCTs on anti-OA drugs.

On the basis of this, and considering the difficulties encountered in pooling the published data for the purpose of meta-analysis, we conceived a draft of a general framework for harms reporting in clinical trial manuscripts. To build expert consensus guidance on the reporting of harms-related data in future anti-OA medication trial manuscripts, we initiated a two-stage modified Delphi process [33,34,35] that involved experts from the ESCEO working group on the safety of anti-OA medications.

This working group included rheumatologists, specialists in physical medicine and rehabilitation, clinical epidemiologists, endocrinologists, pharmacologists, orthopedic surgeons, geriatricians, specialists in public health and health economics, preclinical scientists and representatives of patients with OA. The working group took place on 1 December 2017 in Geneva, Switzerland, where the results of the new meta-analyses on the safety of anti-OA medications were first presented. The majority of the working group members have been clinical investigators for anti-OA medication trials and/or clinicians. All 20 of the members of the ESCEO working group on the safety of anti-OA medications were invited to take part in the consensus-making process.

The Delphi process aimed at reaching consensus on a final general framework for the reporting of harms-related data in manuscripts. An additional consensus was also to be made on the most relevant organ systems to be considered for the reporting of harms within the results sections of manuscripts on RCTs according to each drug class, to take into account journal space constraints [8, 15] and the fact that all AEs arising from a clinical trial cannot be reported within the results section of a manuscript.

The first round of the modified Delphi process consisted of reviewing, commenting on, and improving the first draft of the general framework designed by the lead author (GH). The working group members were asked to add any other subjects they would judge necessary to include in the general framework. This first round took place from 26 July to 31 August 2018. The new ideas were summarized, and the original draft was adapted using the contributions from the working group members. The new draft of the general framework was then submitted to all working group members who contributed to the first round of the consensus-making process for review and consensus. They were asked to consider the relevance, feasibility and usefulness of each item and rate it on a scale of 0–10, expressing their level of agreement on each specific item (0 being “strongly disagree” and 10 “strongly agree”). They were asked to rate the item as highly as they thought it should be recommended. The second round took place from 26 September to 18 October 2018. During this round, the working group members were also asked to select from a list the system organ classes (SOCs) they thought the most relevant (absolutely essential) for harms data reporting within the results section of a manuscript according to each class of drug in OA. The rationale for SOC selection was the mechanism of action of the drug and organ systems that might reasonably be harmed by a specific class of drug [14]; physicians’ and patients’ safety concerns about each drug class were also to be taken into account for selection.

Regarding the general framework for harms reporting, the median rating (within the 25th and 75th percentiles [P25 and P75]) was determined for each item following the second round of the Delphi process to measure the overall degree of agreement on each item. Prior to the calculation of the median ratings, when a working group member rating was < 7 for an item, the responders were asked to comment on their rating so we could understand why they did not express strong agreement with this specific item. Based on these comments, the content of the item was rephrased without modifying the main idea of the recommendation in the specific item. However, the working group member was not asked to give a new rating to the item. A draft of the manuscript describing the ESCEO recommendations for harms reporting in future publications on clinical trials on anti-OA medications was subsequently prepared and submitted to all ESCEO safety working group members for review. All members of the working group agreed with the final version of this consensus paper.

3 Results

3.1 Adverse Event (AE) Reporting Practices in Prior Anti-osteoarthritis (OA) Medication Trial Publications

The articles selected for the ESCEO meta-analyses on the safety of some anti-OA medications [30,31,32] hide important divergence in the reporting of AEs, which we report here. As previously stated, these meta-analyses were aimed at assessing the AEs associated with the use of topical NSAIDs, SYSADOAs and IAHA for the management of OA. The main different ways in which harms-related data were reported in the retrieved articles are summarized in the following six subsections and in Table 1. These diverse reporting practices, which have also been described in other systematic reviews on drugs for other diseases [15, 16], preclude any objective comparison of AEs and AE frequencies between various studies on the same medication, as well as between studies on different drugs for the same disease. Pooling of these kind of diversely reported data is inadequate in meta-analyses [15] or, at least, might lead to a systematic underestimation of harms. Thus, any objective assessment of harm/benefit balance in such context is compromised.

In addition to the main harms-reporting practices summarized hereunder, we also found that, although the total numbers of participants who withdrew from the trials due to AEs or who experienced any severe or serious AEs at least once during the trials were usually reported in the manuscripts, the specific events pertaining to each of these categories were not always reported. In almost all of the articles, we found no reported data about drug effects on biochemical and biological parameters such as full blood count, hemoglobin, and biochemical markers of liver injury and renal function.

3.1.1 Treatment-Emergent vs. Treatment-Related AEs

In some articles, harms were reported as “treatment-emergent AEs” (TEAEs) [36,37,38], defined by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) as events “that emerge during treatment having been absent pre-treatment, or that worsen relative to the pre-treatment state” [39]. Other manuscripts reported only AEs judged by the investigators as “treatment-related AEs” (TRAEs) [40,41,42]. Finally, many other cases did not clearly specify whether the reported AEs were “treatment emergent” or “treatment related” [43, 44].

3.1.2 Relevance of AEs: A Threshold for AE Reporting

Reporting AEs according to frequency of occurrence was very common. Many articles reported only AEs experienced by at least a given percentage of patients in either group (treatment or control). The most common threshold percentages were 2% (i.e., AEs occurring in ≥ 2% of patients in either group) [36, 45], 3% [37], or 5% [46,47,48].

3.1.3 System Organ Class (SOC) vs. Specific AE Reporting

Many articles reported AEs by SOC, providing for each SOC the number of patients who experienced any AE related to that SOC. Sometimes only partial or no details on specific AEs pertaining to each SOC were included [42, 49, 50]. By contrast, other articles reported only a small number of selected specific AEs [47, 51] without providing the overall SOC-related frequencies when many specific AEs pertained to the same SOC.

3.1.4 Reporting in Summary Form and/or Reporting of the Number of AEs

The majority of manuscripts on the efficacy and safety of anti-OA medications reported AE data only in summary form. This summary was usually formulated as: “The most commonly reported AEs in the intervention and control groups were xxx” and/or “There was no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups” and/or “There were no serious AEs in either group” [52,53,54].

Alternatively, rather than listing the AEs and providing the number of patients who experienced each event at least once (the frequency), some manuscript authors reported only the numbers of AEs experienced during the trial [52, 55, 56]. This was usually stated in the form of “The total numbers of AEs in the intervention and placebo groups were # and ## AEs, respectively” or “The numbers of AEs in the two treatment arms were similar: ### AEs occurred in the intervention group and #### AEs in the placebo group.” This kind of information is not relevant in terms of knowledge about harms associated with a given treatment.

3.1.5 Combination of Many of the Previous Reporting Profiles in a Single Manuscript

Very often, many of these previously described reporting practices were combined in a single manuscript. Sometimes, “TRAEs in a defined percentage of patients” [42, 45, 57] or “TEAEs in a defined percentage of patients” [36,37,38] were reported, and these threshold percentages varied between manuscripts reporting data from various RCTs on the same drug. Other cases provided a narrative summary of treatment-related (and/or treatment-unrelated) AEs in the results section of the manuscript to describe harms associated with drugs [40, 58].

3.1.6 AE Coding Systems

Different coding systems were used for the assessment and reporting of AEs in the studies included in the new ESCEO meta-analyses. These included the WHO-Adverse Reaction Terminology (WHO-ART) system [55, 58], the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) [38, 59, 60] and the Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms (COSTART) [44, 61]. Most manuscripts did not specify the AE coding dictionary used [43, 62,63,64].

3.2 The ESCEO Recommendations for Harms Reporting in Future Manuscripts on Studies Assessing Anti-OA Drugs

In total, 20 individuals were first invited to the modified Delphi process (round 1); 15 responded, representing 75% of the original experts contacted. Based on comments from these experts during this first round, the six items originally designed as a general framework for harms reporting were rephrased or improved, leading to a new draft with eight items. Only the 15 experts who completed the first round were then invited to take part in round 2 of the modified Delphi process; all of these participants (100%) rated each recommendation on a scale of 0–10, where 10 represented the highest level of agreement on the item.

For the eight items of the general framework for harms reporting, the median rating of the working group members was 9 (P25 ≥ 7; P75 = 10) for four items, 8 (P25 ≥ 6; P75 ≥ 9) for three items, and 7 (P25 = 6; P75 = 8) for one item. This suggests a high level of agreement on each item. As planned, the working group members who rated an item as < 7 were contacted and asked to comment on their rating. Based on these comments, the item was rephrased for a better consensus on the final version of the recommendation without changing its main theme.

Regarding the SOCs to be considered for AE reporting within the results section of manuscripts, the votes of the members of the working group were counted. For each drug class/group, the SOCs that received ≥ 50% of the votes (≥ 7/14 voters) were retrieved. Some additional SOCs with six votes were also ultimately included by consensus. For the SYSADOAs, “eye disorders” was not originally selected (only three votes initially) but was ultimately added to the SOCs list by consensus. Indeed, a recent RCT on glucosamine reported an increase in intraocular pressure in patients with OA, particularly in older patients [65].

3.2.1 General Framework for Harms Reporting Within the Results Sections of Manuscripts on Anti-OA Drugs

The members of the ESCEO working group on the safety of anti-OA medications agreed on a general framework of recommendations for better reporting of harms in studies assessing drugs for OA. This is summarized in Table 2 and discussed in detail here.

The ESCEO working group first focused on the types of AEs to be reported within the results section of manuscripts and how these should be reported to allow for capturing of all relevant harms. While it is understandable that AEs may differ according to individual drugs and pharmacological classes, reporting the same type of information, in the same way, from various trials of the same drug or of drugs pertaining to the same class appears to be essential. The CONSORT-harms extension statement recommends to “present the absolute risk per arm and per AE type, grade, and seriousness” [10]. However, the “AE type” is not clarified, with the result that manuscript authors may not report the same type of information for different trials on the same drug, and even for trials on different drugs for the same disease. To allow for consistency in the future, and for comparability, the ESCEO proposes a general framework for harms reporting consisting of always reporting AEs by body system.

The other source of variation in the reporting of AEs in clinical trial manuscripts is the coding dictionary used. For the meta-analyses commissioned by the ESCEO to assess the safety profile of various anti-OA medications, almost all of the full safety reports received from pharmaceutical companies and investigators used the MedDRA coding system. Other authors have also reported that MedDRA was one of the most commonly utilized systems for harms reporting around the world [66, 67]. Thus, for consistency in this regard, the ESCEO recommends use of the MedDRA coding system (https://www.meddra.org/) when reporting harms from drugs for OA [68, 69]. However, if another coding system is used (which is not recommended), the ESCEO recommends that this coding system and the reason for not using MedDRA should always be clearly stated in the manuscript. Regardless of the coding system used, the ESCEO recommends that, for each SOC, at least the five most frequent (more if necessary) specific AEs with their frequencies (i.e., the number of participants per arm who experienced each specific AE at least once) are reported. These AEs should be reported whether or not the difference between the intervention and control groups is statistically significant. When the MedDRA dictionary is used for AE reporting, as recommended by the ESCEO, specific AEs should be reported using MedDRA “preferred terms” [68, 69].

Finally, regarding the types of AEs that should be reported, the ESCEO recommends always reporting the total number of patients who experienced at least once any severe AE (highest grade in severity—mild, moderate, severe—for the non-serious AEs) and any serious AE (an AE that results in death, is life-threatening, requires inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or is a congenital anomaly/birth defect) [27]. As well, the total number of patients who withdrew from the trial due to AE(s) and the overall number of patients who experienced any AE (total AEs) at least once during the trial should always be reported, irrespective of the drug. These reports should be made regardless of the SOC. As for the specific AEs for reporting by SOC, at least the top five specific events that led patients to withdraw from the trial should be reported, as well as the top five total AEs. By contrast, ESCEO safety working group members emphasized that all specific severe and serious AEs should always be reported.

The ESCEO safety working group members are aware that the recommendation to report the most frequent specific events (in the intervention group) pertaining to an SOC might pose a different problem. Indeed, the most frequent events might not be clinically relevant, and some more clinically relevant events might be sparse. To avoid missing any clinically relevant information, the working group members recommend separately reporting any other specific event that would be judged as clinically relevant by the clinicians conducting a trial and that would not have been captured by the reporting of serious or severe AEs, or withdrawals due to AE(s), as recommended hereunder. However, as has been seen in studies on diacerein for patients with OA, the most well-known safety issues related to that compound were the most frequent events reported in the full clinical trial reports, particularly regarding gastrointestinal and urinary system disorders [48, 70]. On the other hand, even though the most frequent specific events pertaining to an SOC are not clinically relevant, knowing them may also be important. In fact, this could help physicians to warn patients that they might experience such events (in case of a causal relationship with the treatment) but that they are not severe or serious.

The approach that consists of reporting AEs by body system along with frequencies for specific events pertaining to each body system is supported by the following rationale: when only specific AEs are reported with multiple events pertaining to the same organ class (e.g., vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain), it is impossible to know whether many of them have been experienced by a single patient. In this case, a meta-analysis on the harms related to a specific SOC (e.g., gastrointestinal) will not be feasible or might lead to double counting. Furthermore, for a given drug, when authors of different clinical trials choose to report only the frequencies for specific AEs (and not the SOC level frequencies), each of these authors may not be interested in reporting the same specific events. In such a case, comparing results from various studies might not be easy, because the same events (of interest) might not be reported by different authors.

The second main issue addressed by the ESCEO working group on the safety of anti-OA medications was the thresholds usually chosen by authors to report harms-related data and the choice to report TEAEs or TRAEs. On these points, the working group members recommend that harms should always be reported considering all TEAEs. This excludes any practice consisting of choosing a threshold of occurrence for AEs reporting and/or reporting only the AEs judged as “treatment-related” by clinical investigators, i.e., only based on the judgement of clinicians. As noted by Lineberry et al. [14] in their paper on recommendations to improve AE reporting in clinical trial publications, such judgement by clinicians is subjective and not adequate in the context of randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trials. Notably, the ESCEO experts recommend that these claims of “treatment-related” or “treatment-unrelated” AEs be avoided, particularly for new drugs for which a “definitive” conclusion regarding the safety profile requires results from several trials, considering Hill’s causal criteria [71, 72]. For all drugs (old and new), the working group members recommend that the interpretation of a relationship between an AE and the study drug should only be made in the discussion section of the manuscript, comparing the results obtained from the RCT with those reported from other trials and meta-analyses [71, 73]. This applies also for suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) [74], which regulators compel clinical trial sponsors to report through expedited reporting during the course of clinical trials [27,28,29]. In fact, reporting SUSARs implies an assessment of causality (based on clinicians’ judgments), which the ESCEO discourages from the results sections of manuscripts. Since SUSARs are by default “serious” in nature, they should be reported along with all other serious AEs in the results section as recommended, without any distinction. However, if a serious event qualified as a SUSAR occurred in the course of an RCT, it should be mentioned in the manuscript conclusions (both the conclusion of the main text and that of the summary).

It should be noted that it is extremely difficult (even impossible) to draw a definitive conclusion regarding the safety of drugs in the context of a single clinical trial. Indeed, RCTs are not usually powered to detect differences in AE rates between the intervention and placebo groups but to test hypotheses on efficacy outcomes [16, 75,76,77]. In such context, a real statistically significant difference can exist but might not be detectable [75, 76]. That is why it would not be adequate to base any conclusion on the results of statistical comparison of harms data between the intervention and control groups [15, 77,78,79,80]. Furthermore, a statistically significant or non-significant difference might merely be due to sampling error, a direct result of having drawn a sample from a population [81,82,83]. On the other hand, the risk of bias in RCTs (systematic errors) may more severely affect the results [82, 84,85,86]. Hence, results from several trials and meta-analyses are required to adequately estimate the risk of AEs [15, 77, 80, 87] and to “definitively” conclude on the safety of drugs. What would be appropriate in the context of a single clinical trial, and strongly recommended by the ESCEO, particularly for serious AEs (including SUSARs), is that the characteristics of each patient reporting any serious AE (demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, concomitant drug use, comorbidities, etc.) and the context in which the event occurred are thoroughly assessed. This information should be reported in the discussion section of the manuscript to support the interpretation on relatedness of the event with the studied medication, for each single patient involved. Such an interpretation should always be cautious, reporting in terms of probability of relatedness (strong, weak or uncertain), rather than making strong statements such as “treatment related,” “treatment-unrelated” or “treatment is safe.”

Finally, the ESCEO working group members reached consensus on the recommendation that clinical trial manuscripts should also include information on drug effect on biological and biochemical parameters for both approved and experimental drugs in OA. The relevant biological parameters may differ according to the drug, depending on the drug mechanism of action and the potential for any other adverse biological effects. However, for comparability between drugs and across studies, the ESCEO safety working group recommends that information on drug effects on liver and renal function parameters, as well as on blood cells and hemoglobin, should always be reported whatever the drug, and provide specific guidance on how this information should be reported (see item 7 in Table 2). Regarding the relevance of biological parameters according to drug type, reporting data on glycemia may be important for the SYSADOAs for example, particularly for glucosamine and chondroitin. In the case of biological drugs, it would also be important to collect and report data on antibody immune responses. Data on these particular biological parameters, which are specific to drug types, should be reported on the same model as for the biological parameters that should always be reported irrespective of the drug.

All safety information should be reported in a table that should be included in the results section of the manuscript (see Table 2 and the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]-1).

3.2.2 Recommendations on the Main Body Systems to be Considered for Harms Reporting Within the Results Section of a Manuscript

Table 3 lists the MedDRA SOCs [88] that the ESCEO recommends should always be considered for harms reporting within the results section of a manuscript on anti-OA medications, according to each drug class.

It is important to note that limiting the reporting of body system-related AEs to these SOCs will not result in a loss of information regarding the relevant AEs that would have occurred in the other SOCs. In fact, recommendation number 6 (other clinically relevant AEs) (Table 2) should help capture any other clinically relevant AE that would not have been captured with all the other recommendations. The approach recommended in Table 3 allows for consistency in reporting across several manuscripts, while also considering the space limitations imposed by journal requirements.

4 Discussion

These ESCEO recommendations for the reporting of harms in manuscripts on studies assessing anti-OA drugs complement previous guidelines, particularly the extension of the CONSORT-harms extension statement [10, 14]. The ESCEO recommendations are dedicated to the reporting of clinical trials in OA, focusing on how harms should be reported in the results sections of manuscripts, and the MedDRA SOCs that should be of primary interest for reporting within this section, according to the drug studied. However, these recommendations may also apply to other diseases, particularly those that share the same drugs with OA.

Both the ESCEO recommended general framework and the list of the minimal organ systems to be considered for harms reporting (Tables 2 and 3) should be taken into account when reporting harms associated with anti-OA medications in clinical trial manuscripts. These recommendations are expected to help standardize harms reporting in manuscripts on clinical trials in OA and will allow for better harm/benefit assessment for each medication. They may also contribute to closing the credibility gap surrounding harms reporting and improve the confidence of patients and doctors in anti-OA medications. It is important to note that the current ESCEO recommendations are not to be interpreted as basis for drug approval; as previously stated, they intend to promote transparency and standardization in harms reporting in manuscripts, providing clinicians and clinical researchers (particularly those performing meta-analyses), with more accurate data for comparison of harms results across studies on various anti-OA drugs as well as across various studies on the same drug.

One of the challenges in the implementation of these recommendations may be the manuscript length policies of medical journals [8, 15], since reporting harms-related data as recommended by the ESCEO would require one to two A4 pages (maximum) (see example tables in ESM-1). Indeed, as suggested by Mansi et al. [89], reporting AE data more transparently in the results sections of manuscripts may require that journals revisit their manuscript length policies; however, this should not be impossible for journals to accommodate, since many manuscripts allocate at least the same amount, if not more space, to authors’ names and affiliations as to the reporting of AEs [1, 90]. In addition, in manuscripts of systematic reviews or meta-analyses, tables describing the characteristics of included studies already take up to three pages within the results section [91].

To circumvent the space limitation issue in the comprehensive reporting of all relevant harms within the results sections of manuscripts [16], the idea of reporting AEs (or some of the harms data) as supplementary material on journal websites has emerged [8, 26]. The ESCEO considers that this could indeed be a good idea but is concerned that it might be interpreted as a lack of interest in drug safety as compared with efficacy, since efficacy results are usually extensively reported within the results sections. Of course, the ESCEO does not believe this was the reason for such a suggestion and does consider safety of equal importance to efficacy. In addition, the ESCEO strongly recommends that harms-related data, as agreed by the working group members, should be reported within results sections. However, were it not possible to report all harms-related results in the main body text because of space constraints, the ESCEO considers that the SOC-level and specific AEs pertaining to each SOC as recommended (items 2 and 4, Table 2) may be reported as supplementary material, with comprehensive reference to it in the main article text. In this case, the limitation to the reporting of AEs for the SOCs listed in Table 3 no longer applies; SOC-level and specific AEs pertaining to each SOC should therefore be reported considering all MedDRA SOCs.

Pharmaceutical companies developing OA drugs, and researchers conducting clinical trials, are expected to play their part fully in the implementation of these recommendations besides adhering to guidelines for reporting clinical trial results in regulatory submissions. Until now, and contrary to media reports, the pharmaceutical industry has not been solely responsible for the practice of under-reporting of AE data in manuscripts [92]. Rather, harms reporting in manuscripts in industry-funded studies was found to be better than in non-industry-funded studies [6, 11, 26]. In addition, recent research found that compliance with transparency policies by pharmaceutical companies was better than that by academic organizations and non-commercial funders of clinical research [93,94,95]. The greater adherence of pharmaceutical companies to recommendations may be explained by the requirements of regulatory authorities [15, 16, 26], with which academic researchers are not required to comply, rather than any suboptimal adherence of academic researchers to transparency policies.

It can thus be expected that pharmaceutical companies, who are the main sponsors of trials in OA, will easily and spontaneously comply with the new recommendations. The ESCEO also hopes that authors of non-commercial studies will improve their practice and better comply with transparency policies in future by particularly adhering to the current recommendations.

Many authors have previously suggested that improvement in harms reporting in manuscripts strongly depends on journal editors and reviewers [10, 16]. The ESCEO shares this point of view and encourages journals to refer to these new recommendations in their ‘instructions for authors’ for publications of manuscripts on anti-OA medication trials, alongside the instruction to refer to the CONSORT-harms extension statement. The lack of implementation of recommendations that have been published further to the CONSORT-harms extension statement might be due, in part, to a lack of awareness. Thus, the ESCEO commits to raising awareness among journals to include these new recommendations in their ‘instructions for authors’ and to ask that peer reviewers of manuscripts on OA drugs pay particular attention to this.

References

Ioannidis JPA, Lau J. Completeness of safety reporting in randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285(4):437–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.4.437.

Golder S, Loke YK, Wright K, Norman G. Reporting of adverse events in published and unpublished studies of health care interventions: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2016;13(9):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002127.

Rodgers MA, Brown JVE, Heirs MK, Higgins JPT, Mannion RJ, Simmonds MC, et al. Reporting of industry funded study outcome data: comparison of confidential and published data on the safety and effectiveness of rhBMP-2 for spinal fusion. BMJ (Online). 2013;347(7915):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3981.

Schroll JB, Penninga EI, Gøtzsche PC. Assessment of adverse events in protocols, clinical study reports, and published papers of trials of orlistat: a document analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002101.

Hodkinson A, Gamble C, Smith CT. Reporting of harms outcomes: a comparison of journal publications with unpublished clinical study reports of orlistat trials. Trials. 2016;17(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1327-z.

Smith SM, Chang RD, Pereira A, Shah N, Gilron I, Katz NP, et al. Adherence to CONSORT harms-reporting recommendations in publications of recent analgesic clinical trials: an ACTTION systematic review. Pain. 2012;153(12):2415–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.009.

Péron J, Maillet D, Gan HK, Chen EX, You B. Adherence to CONSORT adverse event reporting guidelines in randomized clinical trials evaluating systemic cancer therapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3957–63. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3981.

Ioannidis JPA. Adverse events in randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1737–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.313.

Pitrou I, Boutron I, Ahmad N, Ravaud P. Reporting of safety results in published reports of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1756–61. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.306.

Ioannidis JPA, Evans SJW, Gøtzsche PC, O’Neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz K, et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(10):781–8. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00009.

Haidich AB, Birtsou C, Dardavessis T, Tirodimos I, Arvanitidou M. The quality of safety reporting in trials is still suboptimal: survey of major general medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(2):124–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.005.

Hodkinson A, Kirkham JJ, Tudur-Smith C, Gamble C. Reporting of harms data in RCTs: a systematic review of empirical assessments against the CONSORT harms extension. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003436.

Sivendran S, Latif A, McBride RB, Stensland KD, Wisnivesky J, Haines L, et al. Adverse event reporting in cancer clinical trial publications. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(2):83–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2219.

Lineberry N, Berlin JA, Mansi B, Glasser S, Berkwits M, Klem C, et al. Recommendations to improve adverse event reporting in clinical trial publications: a joint pharmaceutical industry/journal editor perspective. BMJ (Online). 2016;355:i5078. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5078.

Cornelius VR, Sauzet O, Williams JE, Ayis S, Farquhar-Smith P, Ross JR, et al. Adverse event reporting in randomised controlled trials of neuropathic pain: considerations for future practice. Pain. 2013;154(2):213–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.012.

Smith SM, Wang AT, Katz NP, McDermott MP, Burke LB, Coplan P, et al. Adverse event assessment, analysis, and reporting in recent published analgesic clinical trials: ACTTION systematic review and recommendations. Pain. 2013;154(7):997–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.003.

Juhl C, Lund H, Roos EM, Zhang W, Christensen R. A hierarchy of patient-reported outcomes for meta-analysis of knee osteoarthritis trials: empirical evidence from a survey of high impact journals. Arthritis. 2012;2012:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/136245.

Bellamy N, Kirwan J, Boers M, Brooks P, Strand V, Tugwell P, et al. Recommendations for a core set of outcome measures for future phase III clinical trials in knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis. Consensus development at OMERACT III. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(4):799–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2015.1025029.

Hrnack SA, Barber FA. Managing the pain of knee osteoarthritis. Physician Sportsmed. 2014;42(3):63–70. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2014.09.2077.

Yang W, Liu W, Miao C, Sun H, Li L, Li C. Oral glucosamine hydrochloride combined with hyaluronate sodium intra-articular injection for temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;76(10):2066–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2018.04.031.

Wang SZ, Wu DY, Chang Q, Guo YD, Wang C, Fan WM. Intra-articular, single-shot co-injection of hyaluronic acid and corticosteroids in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(3):1928–34. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2018.6371.

Petterson SC, Plancher KD. Single intra-articular injection of lightly cross-linked hyaluronic acid reduces knee pain in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5114-0.

Brander V, Skrepnik N, Petrella RJ, Jiang GL, Accomando B, Vardanyan A. Evaluating the use of intra-articular injections as a treatment for painful hip osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, parallel-group study comparing a single 6-mL injection of hylan G-F 20 with saline. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.08.018.

Williams MR, McKeown A, Pressman Z, Hunsinger M, Lee K, Coplan P, et al. Adverse event reporting in clinical trials of intravenous and invasive pain treatments: an ACTTION systematic review. J Pain. 2016;17(11):1137–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.07.006.

Hoffer D, Smith SM, Parlow J, Allard R, Gilron I. Adverse event assessment and reporting in trials of newer treatments for post-operative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;60(7):842–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12721.

Hadi MA, McHugh GA, Conaghan PG. Quality of reporting of harms in randomised controlled trials of pharmacological interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Evid Based Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2017-110715.

ICH. Clinical safety data management: definitions and standards for expedited reporting E2A. 27 October 1994.

Parliament EU. Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Off J Eur Communities. 2001;L121/34.

Commission EU. Communication from the Commission: Detailed guidance on the collection, verification and presentation of adverse event/reaction reports arising from clinical trials on medicinal products for human use (CT-3) 11.6.2011. Report no.: 2011/c 172/01.

Honvo G, Leclercq V, Geerinck A, Thomas T, Veronese N, Charles A, et al. Safety of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in osteoarthritis: outcomes of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(Suppl. 1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00661-0.

Honvo G, Reginster J-Y, Rabenda V, Geerinck A, Mkinsi O, Charles A, et al. Safety of symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis: outcomes of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(Suppl. 1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00662-z.

Honvo G, Reginster JY, Rannou F, Rygaert X, Geerinck A, Rabenda V, et al. Safety of intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections in osteoarthritis: outcomes of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(Suppl. 1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00657-w.

Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12:1–8.

Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the delphi method to the use of experts. Manag Sci. 1963;9(3):458–67.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess (Winch Engl). 1998;2(3):1–88. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta2030.

Altman RD, Dreiser RL, Fisher CL, Chase WF, Dreher DS, Zacher J. diclofenac sodium gel in patients with primary hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1991–9. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.081316.

Barthel HR, Haselwood D, Longley S, Gold MS, Altman RD. Randomized controlled trial of diclofenac sodium gel in knee osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39(3):203–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.09.002.

Kneer W, Rother M, Mazgareanu S, Seidel EJ, European Idea-Study Group. A 12-week randomized study of topical therapy with three dosages of ketoprofen in Transfersome gel (IDEA-033) compared with the ketoprofen-free vehicle (TDT 064), in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Pain Res. 2013;6(101540514):743–53. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S51054.

ICH. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline Statistical principles for clinical trials. Stat Med. 1999;18:1903–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990815)18:15%3c1903:aid-sim188%3e3.0.co;2-f.

Altman RD, Akermark C, Beaulieu AD, Schnitzer T, Durolane International Study G. Efficacy and safety of a single intra-articular injection of non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2004;12(8):642–9.

Strand V, Baraf HS, Lavin PT, Lim S, Hosokawa H. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial comparing a single intra-articular injection of Gel-200, a new cross-linked formulation of hyaluronic acid, to phosphate buffered saline for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2012;20(5):350–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2012.01.013.

Conaghan PG, Dickson J, Bolten W, Cevc G, Rother M. A multicentre, randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial comparing the efficacy and safety of topical ketoprofen in transfersome gel (IDEA-033) with ketoprofen-free vehicle (TDT 064) and oral celecoxib for knee pain associated with osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(7):1303–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ket133.

Bookman AA, Williams KS, Shainhouse JZ. Effect of a topical diclofenac solution for relieving symptoms of primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2004;171(4):333–8. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1031793.

Roth SH, Shainhouse JZ. Efficacy and safety of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) in the treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(18):2017–23.

Baraf HS, Gold MS, Clark MB, Altman RD. Safety and efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium 1% gel in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38(2):19.

Michel BA, Stucki G, Frey D, De Vathaire F, Vignon E, Bruehlmann P, et al. Chondroitins 4 and 6 sulfate in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):779–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20867.

Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Rovati LC, Lee RL, Lejeune E, Bruyere O, et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9252):251–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03610-2.

Pelletier JP, Yaron M, Haraoui B, Cohen P, Nahir MA, Choquette D, et al. Efficacy and safety of diacerein in osteoarthritis of the knee: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Diacerein Study Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(10):2339–48.

Frestedt JL, Walsh M, Kuskowski MA, Zenk JL. A natural mineral supplement provides relief from knee osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Nutr J. 2008;7(101152213):9.

Niethard F, Gold MS, Solomon GS, Liu JM, Unkauf M, Albrecht HH, et al. Efficacy of topical diclofenac diethylamine gel in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(12):2384.

Bruhlmann P, Michel BA. Topical diclofenac patch in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(2):193–8.

Jorgensen A, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Simonsen O, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Eriksen C, Bliddal H, et al. Intra-articular hyaluronan is without clinical effect in knee osteoarthritis: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 337 patients followed for 1 year. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1097–102.

Huang T-L, Chang C-C, Lee C-H, Chen S-C, Lai C-H, Tsai C-L. Intra-articular injections of sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan) in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial in the Asian population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(100968565):221.

van der Weegen W, Wullems JA, Bos E, Noten H, van Drumpt RA. No difference between intra-articular injection of hyaluronic acid and placebo for mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. J Arthroplast. 2015;30(5):754–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2014.12.012.

Karlsson J, Sjogren LS, Lohmander LS. Comparison of two hyaluronan drugs and placebo in patients with knee osteoarthritis. A controlled, randomized, double-blind, parallel-design multicentre study. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2002;41(11):1240–8.

Allegrini A, Nuzzo L, Pavone D, Tavella-Scaringi A, Giangreco D, Bucci M, et al. Efficacy and safety of piroxicam patch versus piroxicam cream in patients with lumbar osteoarthritis. A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arzneimittelforschung. 2009;59(8):403–9.

Rother M, Conaghan PG. A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial in moderate osteoarthritis knee pain comparing topical ketoprofen gel with ketoprofen-free gel. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(10):1742–8. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.130192.

Arden NK, Akermark C, Andersson M, Todman MG, Altman RD. A randomized saline-controlled trial of NASHA hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(2):279–86.

Herrero-Beaumont G, Ivorra JA, Del Carmen Trabado M, Blanco FJ, Benito P, Martin-Mola E, et al. Glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study using acetaminophen as a side comparator. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(2):555–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22371.

Rother M, Lavins BJ, Kneer W, Lehnhardt K, Seidel EJ, Mazgareanu S. Efficacy and safety of epicutaneous ketoprofen in transfersome (IDEA-033) versus oral celecoxib and placebo in osteoarthritis of the knee: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1178–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2006.065128.

Baer PA, Thomas LM, Shainhouse Z. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with a topical diclofenac solution: a randomised controlled, 6-week trial [ISRCTN53366886]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2005;6:44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-6-44.

Gabay C, Medinger-Sadowski C, Gascon D, Kolo F, Finckh A. Symptomatic effects of chondroitin 4 and chondroitin 6 sulfate on hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3383–91.

Reginster JY, Dudler J, Blicharski T, Pavelka K. Pharmaceutical-grade chondroitin sulfate is as effective as celecoxib and superior to placebo in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: the ChONdroitin versus CElecoxib versus Placebo Trial (CONCEPT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(9):1537–43. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210860.

Roman-Blas JA, Castaneda S, Sanchez-Pernaute O, Largo R, Herrero-Beaumont G, Group CGCTS. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(1):77–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39819.

Esfandiari H, Pakravan M, Zakeri Z, Ziaie S, Pakravan P, Ownagh V. Effect of glucosamine on intraocular pressure: a randomized clinical trial. Eye (London, England). 2017;31(3):389–94.

Bailey C, Peddie D, Wickham ME, Badke K, Small SS, Doyle-Waters MM, et al. Adverse drug event reporting systems: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12944.

Karmarkar A. Reporting adverse drug reactions: a view on ADR dictionaries. Pharma Utility. 2012;6(6):9–12.

Brown EG, Wood L, Wood S. The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Drug Saf. 1999;20(2):109–17. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-199920020-00002.

Fescharek R, Kübler J, Elsasser U, Frank M, Güthlein P. Medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Int J Pharm Med. 2004;18(5):259–69. https://doi.org/10.2165/00124363-200418050-00001.

Dougados M, Nguyen M, Berdah L, Mazieres B, Vignon E, Lequesne M. Evaluation of the structure-modifying effects of diacerein in hip osteoarthritis: ECHODIAH, a three-year, placebo-controlled trial. Evaluation of the chondromodulating effect of diacerein in OA of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(11):2539–47.

Morabia A. On the origin of Hill’s causal criteria. Epidemiology. 1991;2(5):367–9.

Morabia A. Hume, Mill, Hill, and the sui generis epidemiologic approach to causal inference. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(10):1526–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt223.

Weed DL. Interpreting epidemiological evidence: how meta-analysis and causal inference methods are related. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(3):387–90.

Perez C, Olivier P, Lortal B, Duranton S, Montastruc JL, Colin AL, et al. Detection of drug safety signals from clinical trials data: role of SUSARs. Pharmacol Res. 2018;131:218–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2018.02.010.

Tsang R, Colley L, Lynd LD. Inadequate statistical power to detect clinically significant differences in adverse event rates in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(6):609–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.005.

Papanikolaou PN, Christidi GD, Ioannidis JPA. Comparison of evidence on harms of medical interventions in randomized and nonrandomized studies. CMAJ. 2006;174(5):635–41. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050873.

Singh S, Loke YK. Drug safety assessment in clinical trials: methodological challenges and opportunities. Trials. 2012;13:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-138.

Altman DG, Bland JM. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 1995;311:485.

Slutsky D. Statistical errors in clinical studies. J Wrist Surg. 2013;02(04):285–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1359421.

Alderson P. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 2004;328(7438):476–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7438.476.

Sedgwick P. What is sampling error? BMJ (Online). 2012;344(7863):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e4285.

Altman DG, Bland JM. Uncertainty beyond sampling error. BMJ (Online). 2014;349(November):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7065.

Sedgwick P. Uncertainty in sample estimates: sampling error. BMJ. 2015;350:h1914. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1914.

Buyse M, Squifflet P, Coart E, Quinaux E, Punt CJA, Saad ED. The impact of data errors on the outcome of randomized clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2017;14(5):499–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774517716158.

Gluud LL. Bias in clinical intervention research. AJE. 2006;163(6):493–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwj069.

Keirse MJNC, Hanssens M. Control of error in randomized clinical trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92(1):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-2115(00)00455-3.

Sterne JAC, Smith GD. Sifting the evidence—what’s wrong with significance tests? Phys Ther. 2001;81(8):1464–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/81.8.1464.

ICH. Introductory guide MedDRA version 21.0 March 2018; Report no.: 000148.

Mansi BA, Clark J, David FS, Gesell TM, Glasser S, Gonzalez J, et al. Ten recommendations for closing the credibility gap in reporting industry-sponsored clinical research: a joint journal and pharmaceutical industry perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(5):424–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.009.

Favier R, Crepin S. The reporting of harms in publications on randomized controlled trials funded by the “Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique,” a French academic funding scheme. Clin Trials. 2018;15(3):257–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774518760565.

Kroon FPB, Carmona L, Schoones JW, Kloppenburg M. Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological, pharmacological and surgical treatment for hand osteoarthritis: a systematic literature review informing the 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000734. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000734.

Golder S, Loke YK. Is there evidence for biased reporting of published adverse effects data in pharmaceutical industry-funded studies? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(6):767–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03272.x.

Goldacre B, Lane S, Mahtani KR, Heneghan C, Onakpoya I, Bushfield I, et al. Pharmaceutical companies’ policies on access to trial data, results, and methods: audit study. BMJ (Online). 2017;358(July):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3334.

DeVito NJ, French L, Goldacre B. Noncommercial funders’ policies on trial registration, access to summary results, and individual patient data availability. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1721–3.

Mayo-Wilson E, Heyward J, Keyes A, Reynolds J, White S, Atri N, et al. Clinical trial registration and reporting: a survey of academic organizations in the United States. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1042-6.

Acknowledgements

This paper is written on behalf of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) Working Group on the safety of anti-osteoarthritis medications: Nasser Al-Daghri, Nigel Arden, Bernard Avouac, Olivier Bruyère, Roland Chapurlat, Philip Conaghan, Cyrus Cooper, Elizabeth Curtis, Elaine Dennison, Nicholas Fuggle, Gabriel Herrero-Beaumont, Germain Honvo, Margreet Kloppenburg, Stefania Maggi, Tim McAlindon, Alberto Migliore, Ouafa Mkinsi, François Rannou, Jean-Yves Reginster, René Rizzoli, Roland Roth, Thierry Thomas, Daniel Uebelhart, and Nicola Veronese. The ESCEO is indebted to the Delphi panel members who took part in all stages of the Delphi process: Bernard Avouac, Olivier Bruyère, Philip Conaghan, Elizabeth Curtis, Elaine Dennison, Nicholas Fuggle, Gabriel Herrero-Beaumont, Margreet Kloppenburg, Ouafa Mkinsi, François Rannou, Jean-Yves Reginster, René Rizzoli, Lucio Rovati, Daniel Uebelhart, and Nicola Veronese. Without their invaluable contribution, it would not have been possible to complete these recommendations. The ESCEO would also like to acknowledge the invaluable contribution of Dr Raveendhara R. Bannuru, whose expertise has been of high importance in the preparation of these recommendations. P.G. Conaghan is supported in part by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors would like to express their most sincere gratitude to Dr Lisa Buttle for her invaluable help with manuscript preparation. Dr Lisa Buttle was entirely funded by the ESCEO asbl, Belgium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to this version to be published.

Funding

G Honvo was funded by the ESCEO, a Belgian not-for-profit organization. The ESCEO Working Group was entirely funded by the ESCEO. The ESCEO receives unrestricted educational grants to support its educational and scientific activities from non-governmental organizations, not-for-profit organizations, non-commercial, and corporate partners. The choice of topics, participants, content and agenda of the working groups as well as the writing, editing, submission, and reviewing of the manuscript are the sole responsibility of the ESCEO, without any influence from third parties.

Conflict of interest

O Bruyere reports grants from Biophytis, IBSA, MEDA, Servier, SMB, and Theramex, outside of the submitted work. C. Cooper reports personal fees from Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Eli Lilly, GSK, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Takeda, and UCB, outside of the submitted work. J-Y. Reginster reports grants from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, Radius Health (through institution), consulting fees from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, Radius Health, and Pierre Fabre; fees for participation in review activities from IBSA-Genevrier, MYLAN, CNIEL, Radius Health, and Teva; payment for lectures from AgNovos, CERIN, CNIEL, Dairy Research Council (DRC), Echolight, IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, Pfizer Consumer Health, Teva, and Theramex, outside of the submitted work. N. Arden reports personal fees from Bioventus, Flexion, Merck, Pfizer/Lilly, Regeneron, Smith & Nephew, and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and grants from Bioiberica and Merck, outside the submitted work. P.G. Conaghan reports consultancy or speakers’ bureaus fees from Abbvie, BMS, Flexion Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Serono, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Samumed outside of the submitted work. F. Rannou reports grants from APHP, INSERM, University Paris Descartes, and Arthritis (Road Network) and consulting fees from Pierre Fabre, Expanscience, Thuasne, Servier, Genevrier, Sanofi Aventis, and Genzyme, outside of the submitted work. T. McAlindon reports fees for participation in review activities from Pfizer and fees for consulting activities from Flexion, Samumed, Sanofi, Visgo, Roche, Astellas, Pfizer, Seikayaku, Regeneron, and Anika, outside of the submitted work. T. Thomas reports personal fees from Abbvie, Amgen, Arrow, BMS, Chugai, Expanscience, Gilead, HAC-Pharma, LCA, Lilly, Medac, MSD, Pfizer, Thuasne, TEVA, and UCB and grants from Amgen, Bone Therapeutics, Chugai, HAC-Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB, outside of the submitted work. R. Bannuru was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (K23AT009374) and reports honorarium from Sanofi, Bioventus, and Fidia, outside of the submitted work. G. Honvo, G. Herrero-Beaumont, and D. Uebelhart have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Honvo, G., Bannuru, R.R., Bruyère, O. et al. Recommendations for the Reporting of Harms in Manuscripts on Clinical Trials Assessing Osteoarthritis Drugs: A Consensus Statement from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Drugs Aging 36 (Suppl 1), 145–159 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00667-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-019-00667-8