Abstract

Introduction

It is unknown whether the cardiovascular risks associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use differ according to lifestyle and socioeconomic position.

Objective

We examined the association between NSAID use and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within subgroups defined by lifestyle and socioeconomic position.

Methods

We conducted a case-crossover study of all adult first-time respondents to the Danish National Health Surveys of 2010, 2013, or 2017, without previous cardiovascular disease, who experienced a MACE from survey completion through 2020. We used a Mantel-Haenszel method to obtain odds ratios (ORs) of the association between NSAID use (ibuprofen, naproxen, or diclofenac) and MACE (myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, heart failure, or all-cause death). We identified NSAID use and MACE via nationwide Danish health registries. We stratified the analyses by body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity level, marital status, education, income, and employment.

Results

Compared with non-use, the OR of MACE was 1.34 (95% confidence interval: 1.23–1.46) for ibuprofen, 1.48 (1.04–2.43) for naproxen, and 2.18 (1.72–2.78) for diclofenac. When comparing NSAID use with non-use or the individual NSAIDs with each other, we observed no notable heterogeneity in the ORs within subgroups of lifestyle and socioeconomic position for any NSAID. Compared with ibuprofen, diclofenac was associated with increased risk of MACE in several subgroups with high cardiovascular risk, e.g., individuals with overweight (OR 1.52, 1.01–2.39) and smokers (OR 1.54, 0.96–2.46).

Conclusions

The relative increase in cardiovascular risk associated with NSAID use was not modified by lifestyle or socioeconomic position.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Compared with non-use, use of ibuprofen, naproxen, or diclofenac was associated with increased risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event. |

This increased risk was not modified by lifestyle or socioeconomic position. |

Compared with use of ibuprofen or naproxen, use of diclofenac was associated with a larger increased risk of a major adverse cardiovascular event in several subgroups with high cardiovascular risk. |

1 Introduction

The European Society of Cardiology warns against use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in individuals with modifiable cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and smoking [1]. Yet NSAIDs remain frequently used by such individuals [2, 3], and, by extension, by individuals with socioeconomic determinants for cardiovascular disease [3].

Examining whether the NSAID-associated cardiovascular risks differ according to lifestyle and socioeconomic position is clinically relevant because of the increased baseline cardiovascular risk associated with high body mass index [6, 7], smoking [8], physical inactivity [9, 10], being unmarried [11], short education [12], and unemployment [13]. As a result, the cardiovascular risks related to NSAID use could vary between individuals with and without these risk factors.

We, therefore, examined whether the relative cardiovascular risk increase associated with NSAID use varied according to subgroups defined by lifestyle and socioeconomic position.

2 Methods

2.1 Setting

The Danish healthcare system provides all Danish citizens and legal residents with universal tax-supported healthcare, guaranteeing unfettered access to general practitioners, specialists in private practices, and hospitals, as well as partial reimbursement for the costs of prescription drugs [4]. Individual-level linkage of all Danish registries is possible using the unique 10-digit Civil Personal Register number assigned to each Danish citizen at birth and to residents upon immigration [5]. The Danish Civil Registration System contains nationwide data on mortality and migration since 1968 [5], permitting virtually complete follow-up with accurate censoring at death or emigration.

2.2 Study Population and Design

We conducted a case-crossover study [6] of all adult (≥ 18 years of age) first-time respondents to the Danish National Health Surveys of 2010, 2013, or 2017 [7], who died or experienced a cardiovascular event between survey completion and 31 December 2020. The nationwide Danish National Health Survey was conducted in one national and five regional random samples of approximately 300,000 individuals ≥ 16 years of age in each survey year [7]. Since the date of completion of the survey was unavailable, we used 1 May in the survey year as the index date. We chose this date as the survey was administered between the end of January and the beginning of May in each survey year [7]. Individuals with a prior hospital diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (International Classification of Diseases 10th edition code: DI) were excluded as those with and without manifest cardiovascular disease may vary in cardiovascular risk. We also excluded individuals with a filling of an NSAID prescription (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification code: M01A) in the year before survey completion, as prevalent and new NSAID users may have different cardiovascular risks.

2.3 NSAID Use

The exposures were the NSAIDs ibuprofen, naproxen, or diclofenac, as they account for most filled NSAID prescriptions in Denmark [8]. The length of exposure was determined by utilizing information on the dosage and the number of tablets from filled prescriptions of these drugs. This approach might be more precise than using fixed time windows [9, 10]. The exposure length was calculated as the prescribed quantity divided by half of the maximum daily dose recommended by Danish guidelines for pain or fever treatment (600 mg for ibuprofen, 500 mg for naproxen, and 100 mg for diclofenac). Thus, a patient who filled an ibuprofen prescription with 50 tablets of 400 mg was considered exposed to ibuprofen for the next 33 days (50x400/600 = 33). If a patient filled a new prescription for the same NSAID within an exposure period plus a 30-day grace period, the exposure period was extended by the number of days provided by the new prescription. We identified NSAID prescriptions from the Danish National Prescription Registry, which contains accurate information on all filled prescriptions from Danish community pharmacies since 1995 [11].

2.4 Outcomes

The primary outcome was a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), defined as a composite of the major cardiovascular risks associated with use of NSAIDs, i.e., myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, heart failure, and all-cause death [12, 13]. Secondary outcomes were the individual MACE components. We identified the outcome dates from the Danish National Patient Registry, which contains information on all inpatient non-psychiatric contacts since 1977 and on all inpatient psychiatric, emergency, and outpatient contacts since 1995 [14]. Registration of the International Classification of Diseases codes used to define the outcomes have all been validated within the Danish National Patient Registry with positive predictive values of 97% for myocardial infarction [15], 88% for ischemic stroke [16], and 76% for heart failure [15]. All International Classification of Diseases and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification codes used in the study are provided in Online Resource 1.

2.5 Lifestyle and Socioeconomic Position

Lifestyle and socioeconomic position were categorized as presented in Online Resource 2 based on self-reported answers to questions in the Danish National Health Surveys [7] and information on income [17] and employment [18] available from Danish registries.

2.6 Covariates

We used the Quan-modified Charlson Comorbidity Index to estimate baseline comorbidity burden, categorized as no (score: 0), low (score: 1), moderate (score: 2–3), or severe (score: ≥ 4) [19, 20]. To assign comorbidities to individuals, we used in and outpatient information for the 10 years preceding the outcome date. In addition to hospital diagnoses, we used drug proxies for diabetes without chronic complications, chronic pulmonary disease, affective disorder, and hypertension because these may be treated solely by a general practitioner. These proxies were at least one filled prescription for a drug used to treat diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, or depression, or at least two filled prescriptions for two different antihypertensive drug classes during the 3 months before outcome date. For other drugs, we defined baseline drug use based on filling of a prescription during the 3 months before outcome date.

2.7 Statistical Analyses

We reported patient characteristics for descriptive purposes, using counts with percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables. The case-crossover design is described in detail elsewhere [6, 21]. Briefly, among patients experiencing an outcome, we compared the number of individuals exposed on the outcome date, but not on 120, 180, 240, or 300 days before the outcome date (i.e., the ‘reference’ dates), with the number of individuals exposed on a reference date, but not on the outcome date (Fig. 1). If the exposure period of a prescription covered the outcome or reference dates, this date was considered exposed. Using the Mantel–Haenszel method [22], we hereby obtained the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) associated with being exposed on the outcome date, but not on a reference date. This ‘fixed dates’ approach was preferred over a ‘fixed windows’ approach. Where the former uses one outcome date and several reference dates, the latter stacks windows of fixed lengths backwards in time from the outcome date. These windows are then considered exposed if there is a filled prescription within them. The fixed dates approach was chosen for two reasons. First, it allowed for flexibility in estimating exposure lengths. Second, it provided a clearer exposure definition, as the outcome and reference dates were only considered exposed if an exposure period covered that date. We ensured a washout period by having a greater gap between the outcome date and the most recent reference date (120 days) than between the reference dates themselves (60 days). Because each individual serves as his/her own control, the case-crossover design eliminates confounding by covariates that are stable over time (e.g., genetics). We used the simple ratio approach to compare ibuprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac with each other [23].

Schematic overview of the case-crossover design. NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. The case-crossover design compares—among patients experiencing the outcome—the number of individuals exposed on the outcome date, but not on the reference date, with the number of individuals exposed on the reference date, but not on the outcome date. Mantel–Haenszel method is used to calculate the odds ratios of being exposed on the outcome date vs. on the reference date, by dividing the first pattern with the second pattern. Patient #1 is exposed on the outcome date. Patient #2 is exposed on the second reference point. Patient #3 is exposed neither on the outcome date or any reference points and is dropped from the analysis

In two sensitivity analyses, we changed the grace period from 30 days to 14 and 60 days because increasing grace periods are associated with increasing treatment duration [24]. In a third sensitivity analysis, we defined daily NSAID use as three daily tablets of ibuprofen, two daily tablets of naproxen, and two daily tablets of diclofenac at the prescribed dose—no matter the tablet dosage.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of the Study Population

Among 472,342 completed surveys, 277,725 (59%) were completed by first-time respondents ≥ 18 years of age without a previous cardiovascular disease diagnosis or a filled NSAID prescription during the year before survey completion, alive 1 May in the survey response year (Online Resource 3). Among these respondents, 22,834 (4.8%) died or were hospitalized for myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or heart failure between survey completion and 31 December 2020, and thus comprised the study population (Online Resource 3). The median age of the individuals experiencing the outcome was 68 years (interquartile range: 59–77 years), 10,144 (44%) were females, and 12,695 (56%) had at least one comorbidity (Table 1). The most common comorbidities were hypertension (23%), malignancy (6.9%), and chronic pulmonary disease (6.5%; Online Resource 4). The most frequently used drugs were antiplatelets (32%), statins (29%), and beta blockers (17%; Online Resource 4). For the main analysis, the numbers of discordant pairs, and thus the number contributing with information to the analysis, were 2,064 for ibuprofen, 108 for naproxen, and 259 for diclofenac.

3.2 Risk of MACE

Compared with NSAID use on a reference date, the OR of MACE associated with NSAID use on the outcome date was 1.34 (95% CI 1.23–1.46) for ibuprofen use, 1.48 (95% CI 1.04–2.09) for naproxen use, and 2.18 (95% CI 1.72–2.78) for diclofenac use (Table 2). Ibuprofen use on the outcome date vs. on a reference date was associated with an increased risk of heart failure (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.06–1.76) and all-cause death (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.27–1.56; Online Resource 5). Naproxen use on the outcome date vs. on a reference date was not associated with an increased risk of any cardiovascular event, but was associated with an increased risk of all-cause death (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.08–2.33; Online Resource 5). Similarly, diclofenac use on the outcome date vs. on a reference date was not associated with an increased risk of any cardiovascular event, but was associated with an increased risk of all-cause death (OR 2.76, 95% CI 2.11–3.60; Online Resource 5).

Compared with ibuprofen use, the risk of MACE was similar for naproxen use (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.77–1.57) and larger for diclofenac use (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.25–2.08; Table 3). Diclofenac use was associated with a larger risk of all-cause death than use of ibuprofen (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.47–2.61) and naproxen (OR 1.74, 1.09–2.77; Online Resource 6).

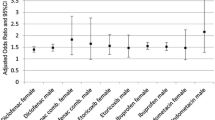

3.3 Differences According to Lifestyle and Socioeconomic Position

When comparing NSAID use on the outcome date with NSAID use on a reference date, we observed no differences in the risk of MACE within subgroups of lifestyle and socioeconomic position for neither use of ibuprofen, naproxen, nor diclofenac (Table 2). The strongest associations with MACE for use of ibuprofen on the outcome date vs. on a reference date were for underweight individuals (OR 1.55, 95% CI 0.88–2.72), individuals with a moderate or high-risk alcohol consumption (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.34–1.90), and individuals with a high physical activity level (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.04–3.52).

Similarly, when comparing the individual NSAIDs with each other, we observed no differences in the risk of MACE within subgroups of lifestyle and socioeconomic position when comparing use of naproxen or diclofenac with ibuprofen use or when comparing diclofenac use with naproxen use (Table 3). Use of ibuprofen and naproxen were associated with comparable cardiovascular risks in all subgroups, whereas diclofenac use had a stronger association with MACE than use of ibuprofen and naproxen in several subgroups (Table 3). For diclofenac use compared with ibuprofen use, the strongest associations with MACE were for never married individuals (OR 3.01, 95% CI 1.20–7.55); individuals with a university degree or higher (OR 5.56, 95% CI 1.68–18.3); and individuals with another employment status than employed, unemployed, or pension (OR 3.86, 95% CI 0.97–15.3). Furthermore, compared with ibuprofen use, diclofenac use was associated with an increased risk of MACE in individuals with overweight (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.01–2.30), smokers (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.96–2.46), and with a low physical activity level (OR 2.71, 95% CI 1.63–4.49).

3.4 Sensitivity Analyses

The results were robust after changing the grace period from 30 days to 14 and 60 days (data not shown). Defining NSAID use as three daily tablets of ibuprofen, two daily tablets of naproxen, and two daily tablets of diclofenac, no matter the tablet dosage, resulted in slightly lower point estimates of the association between NSAID use and MACE, but we did still not observe any differences in the risk of MACE within subgroups of lifestyle and socioeconomic position for any NSAID (data not shown).

4 Discussion

We found that compared with use of NSAIDs 120, 180, 240, or 300 days prior to the outcome date, the risk of MACE associated with use of NSAIDs on the outcome date was increased for patients taking ibuprofen, naproxen, or diclofenac. Compared with ibuprofen use, diclofenac use was associated with higher relative risk increases in several subgroups of lifestyle and socioeconomic position, including individuals with the modifiable cardiovascular risk factors overweight, smoking, and physical inactivity. When comparing NSAID use on the outcome date with NSAID use on a reference date, or when comparing the individual NSAIDs with each other, we observed no notable heterogeneity in the effect estimates within subgroups of lifestyle and socioeconomic position for any NSAID.

4.1 Differences According to Lifestyle and Socioeconomic Position

To our knowledge, no previous study has investigated whether NSAID-associated cardiovascular risks depend on lifestyle or socioeconomic position. It is considered established that the categories of lifestyle and socioeconomic position used to define subgroups in our study generally increase cardiovascular risk [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. One could speculate that the relative cardiovascular risk increase associated with NSAID use would be lower in subgroups with than without modifiable and/or socioeconomic cardiovascular risk factors. Our findings suggest otherwise, as we did not observe any noteworthy differences between subgroups of lifestyle or socioeconomic position.

However, concern is raised by frequent use of NSAIDs among individuals with modifiable or socioeconomic cardiovascular risk factors. Guidance that stresses the importance of already established recommendations from cardiovascular societies regarding restricted NSAID use in high-risk individuals is needed [1]. Since general practitioners are responsible for 86–91% of all NSAID prescriptions in Denmark [2], focused initiatives aimed at changing the prescription patterns of general practitioners may be beneficial. In other settings in which prescriptions from specialists in private practices or hospitals constitute a larger proportion of NSAID prescriptions—or where NSAIDs are more freely available over-the-counter—the focused initiatives should be similarly shifted.

4.2 NSAIDs and Cardiovascular Events

NSAIDs are believed to increase cardiovascular risk through several mechanisms including increased atherogenesis in early stages of atherosclerosis [45] and increased systolic blood pressure [46]. Also, more cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors (like diclofenac) [47] may facilitate platelet aggregation by altering the equilibrium between thromboxane A2 (prothrombotic) and prostacyclin (antithrombotic) [48].

One meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials found that ibuprofen increased the risk of myocardial infarction by 61%, stroke by 236%, and all-cause death by 77%, and that diclofenac increased the risk of stroke by 186% and all-cause death by 131% [13]. Lower estimates have been reported in meta-analyses of observational studies [49, 50]. In one meta-analysis of observational studies, ibuprofen was associated with a 14% increased risk of myocardial infarction, and diclofenac was associated with a 38% increased risk of myocardial infarction [50]. In another meta-analysis of observational studies, the risk of a cardiac event was increased by 17% for ibuprofen and naproxen and 30% for diclofenac [49]. Overall, our results lie between those for meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials [12, 13] and those for observational studies [49, 50]. In alignment with existing literature, we found a higher cardiovascular risk associated with diclofenac use compared with use of ibuprofen or naproxen.

4.3 Limitations

In the case-crossover study, individuals with concordant exposure status on the outcome and reference dates were dropped from the analyses. Because over-the-counter ibuprofen sales account for approximately one-third of total NSAID sales in Denmark [8] and we lacked information on both over-the-counter and in-hospital NSAID use [11], some individuals might have been classified wrongly as non-users rather than as users of over-the-counter ibuprofen or users of NSAIDS in the inpatient setting. Thus, a chronic NSAID user could have been classified incorrectly as a transient user, resulting in discordant exposure status and thereby inclusion in the analyses. However, because of the partial reimbursement for prescription drug costs provided by the Danish healthcare system, regular NSAID users have an incentive to buy their drugs via prescription rather than over-the-counter. Also, since data in the Danish registries are collected prospectively, individuals were unaware of future outcomes at the time of NSAID use. Consequently, such exposure misclassification is likely to be non-differential, producing ORs closer to a null association than otherwise.

Because the Danish National Patient Registry does not contain information on daily dose or length of treatment [11], we had to base NSAID exposure periods on prior knowledge. We did not have any information on adherence after filling of an NSAID prescription. The comparable results observed after changing the duration of the grace period and redefining NSAID use, however, support the robustness of our findings.

The information on lifestyle and socioeconomic position was collected through questionaries, which could result in information bias among subgroups. Again, because of the protective data collection, individuals were unaware of their future outcomes. This favored non-differential misclassification, biasing ORs towards a null association. However, because of polytomous subgroups, bias away from the null in the middle subgroups of categorical variables with more than two levels cannot be ruled out [51].

We used drug proxies to account for diseases that may only be treated by a general practitioner, but this approach may result in incorrect assignment of diseases for some individuals as certain drugs can be used for multiple purposes. For example, in Denmark some antidepressants can be used for depression, anxiety, and neuropathic pain [52].

Despite the case-crossover design being immune to confounding by covariates that are stable over time, the design remains susceptible to confounding caused by time-varying covariates [6]. It is important to note that the results comparing NSAID use with no use are susceptible to confounding-by-indication, as the reason for filling an NSAID prescription is likely time-dependent [23]. Therefore, the comparison of the individual NSAIDs with each other is more appropriate for determining the relative magnitude of the cardiovascular risk. We chose not to compare NSAID use with acetaminophen (paracetamol) use as acetaminophen may also inhibit COX enzymes in a manner similar to NSAIDs [53] and increase cardiovascular risk [54,55,56]. We had no information on systolic blood pressure or blood lipid levels, making us unable to examine the potential association between NSAID use and cardiovascular events and death mediated through hypertension [57] or hyperlipidemia [58]. Moreover, we were not able to assess the association between NSAID use and death due to cardiovascular causes because of too few cardiovascular deaths. Although we used a composite outcome to increase precision [59], we also examined the associations between NSAID use and the individual components of the composite outcome to gain insights into potential underlying mechanisms [60,61,62].

5 Conclusion

The increased relative risk of MACE associated with use of ibuprofen, naproxen, or diclofenac did not differ considerably according to lifestyle and socioeconomic position. However, as individuals with higher baseline cardiovascular risk also carry higher absolute risk increases associated with NSAID use [12, 63], the higher cardiovascular risks observed for diclofenac use compared with use of ibuprofen or naproxen, should serve as warning against prescribing diclofenac independent of lifestyle and socioeconomic position.

References

Schmidt M, Lamberts M, Olsen AM, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: review and position paper by the working group for Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1015–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv505.

Schmidt M, Pottegård A. Prescriber responsibility, predictors for initiation, and 20-year trends in use of non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with cardiovascular contraindications: a nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa073.

Bonnesen K, Ehrenstein V, Grønkjaer MS, et al. Impact of lifestyle and socioeconomic position on use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a population-based cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.5571.

Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563–91. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S179083.

Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:541–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3.

Hallas J, Pottegård A. Use of self-controlled designs in pharmacoepidemiology. J Intern Med. 2014;275:581–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12186.

Christensen AI, Lau CJ, Kristensen PL, et al. The Danish National Health Survey: study design, response rate and respondent characteristics in 2010, 2013 and 2017. Scand J Public Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820966534.

Schmidt M, Hallas J, Friis S. Potential of prescription registries to capture individual-level use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Denmark: trends in utilization 1999–2012. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:155–68. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S59156.

van Staa TP, Abenhaim L, Leufkens H. A study of the effects of exposure misclassification due to the time-window design in pharmacoepidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:183–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90023-x.

Sinnott SJ, Polinski JM, Byrne S, et al. Measuring drug exposure: concordance between defined daily dose and days’ supply depended on drug class. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69(107–113):20150604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.026.

Pottegård A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H, et al. Data resource profile: the Danish National Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:798–798f. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw213.

Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet (London, England). 2013;382(769–779):20130530. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60900-9.

Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2011;342:c7086. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c7086.

Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–90. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S91125.

Sundbøll J, Adelborg K, Munch T, et al. Positive predictive value of cardiovascular diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry: a validation study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012832. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012832.

Johnsen SP, Overvad K, Sørensen HT, et al. Predictive value of stroke and transient ischemic attack discharge diagnoses in the Danish National Registry of Patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:602–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00391-8.

Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:103–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811405098.

Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:95–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811408483.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq433.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83.

Maclure M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:144–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115853.

Kubota K, Kelly TL, Sato T, et al. A novel weighting method to remove bias from within-subject exposure dependency in case-crossover studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01408-5.

Hallas J, Whitaker H, Delaney JA, et al. The use of active comparators in self-controlled designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190:2181–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab110.

Gardarsdottir H, Souverein PC, Egberts TC, et al. Construction of drug treatment episodes from drug-dispensing histories is influenced by the gap length. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(422–427):20091031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.07.001.

Khan SS, Ning H, Wilkins JT, et al. Association of body mass index with lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and compression of morbidity. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:280–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0022.

Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet (London, England). 2009;373(1083–1096):20090318. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60318-4.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case–control study. Lancet (London, England). 2004;364:937–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17018-9.

Prescott E, Hippe M, Schnohr P, et al. Smoking and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men: longitudinal population study. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1998;316:1043–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7137.1043.

Chamberlain AM, Agarwal SK, Folsom AR, et al. Smoking and incidence of atrial fibrillation: results from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(1160–1166):20110315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.03.038.

Mons U, Müezzinler A, Gellert C, et al. Impact of smoking and smoking cessation on cardiovascular events and mortality among older adults: meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies of the CHANCES consortium. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2015;350(h1551):20150420. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1551.

Reynolds K, Lewis B, Nolen JD, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;289:579–88. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.5.579.

Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, et al. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2437–45. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.22.2437.

Corrao G, Rubbiati L, Bagnardi V, et al. Alcohol and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2000;95:1505–23. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015056.x.

Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW 3rd, et al. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276:205–10.

Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, et al. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:605–13. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm198603063141003.

Kershaw KN, Droomers M, Robinson WR, et al. Quantifying the contributions of behavioral and biological risk factors to socioeconomic disparities in coronary heart disease incidence: the MORGEN study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(807–814):20130914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-013-9847-2.

Méjean C, Droomers M, van der Schouw YT, et al. The contribution of diet and lifestyle to socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(5190–5195):20130729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.07.188.

Rosengren A, Subramanian SV, Islam S, et al. Education and risk for acute myocardial infarction in 52 high, middle and low-income countries: INTERHEART case-control study. Heart (Br Card Soc). 2009;95(2014–2022):20091012. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2009.182436.

Woodward M, Peters SA, Batty GD, et al. Socioeconomic status in relation to cardiovascular disease and cause-specific mortality: a comparison of Asian and Australasian populations in a pooled analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(e006408):20150317. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006408.

Kilander L, Berglund L, Boberg M, et al. Education, lifestyle factors and mortality from cardiovascular disease and cancer. A 25-year follow-up of Swedish 50-year-old men. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1119–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.5.1119.

Dupre ME, George LK, Liu G, et al. The cumulative effect of unemployment on risks for acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1731–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.447.

Meneton P, Kesse-Guyot E, Méjean C, et al. Unemployment is associated with high cardiovascular event rate and increased all-cause mortality in middle-aged socially privileged individuals. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(707–716):20141111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0997-7.

Wong CW, Kwok CS, Narain A, et al. Marital status and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart (Br Card Soc). 2018;104(1937–1948):20180619. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313005.

Hu B, Li W, Wang X, et al. Marital status, education, and risk of acute myocardial infarction in Mainland China: the INTER-HEART study. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(123–129):20120114. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.je20100175.

Metzner J, Popp L, Marian C, et al. The effects of COX-2 selective and non-selective NSAIDs on the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. J Mol Med (Berlin, Germany). 2007;85:623–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-007-0162-9.

Aw TJ, Haas SJ, Liew D, et al. Meta-analysis of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and their effects on blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(490–496):20050214. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.5.IOI50013.

Bonnesen K, Schmidt M. Re-categorization of non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) according to clinical relevance: abandoning the ‘traditional NSAID’ terminology. Can J Cardiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2021.06.014.

Grosser T, Yu Y, Fitzgerald GA. Emotion recollected in tranquility: lessons learned from the COX-2 saga. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:17–33. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-011209-153129.

Martín Arias LH, Martín González A, Sanz Fadrique R, et al. Cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and classical and selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59(55–73):20180911. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.1302.

Varas-Lorenzo C, Riera-Guardia N, Calingaert B, et al. Myocardial infarction and individual nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:559–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3437.

Jurek AM, Greenland S, Maldonado G, et al. Proper interpretation of non-differential misclassification effects: expectations vs observations. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:680–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyi060.

Tricykliske antidepressiva (TCA). https://pro.medicin.dk/Laegemiddelgrupper/Grupper/243030. Accessed 4 Feb 2023.

Hinz B, Cheremina O, Brune K. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in man. FASEB J. 2008;22(383–390):20070920. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-8506com.

Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, et al. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:552–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206914.

Zeng C, Rosenberg L, Li X, et al. Sodium-containing acetaminophen and cardiovascular outcomes in individuals with and without hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:1743–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac059.

MacIntyre IM, Turtle EJ, Farrah TE, et al. Regular acetaminophen use and blood pressure in people with hypertension: the PATH-BP trial. Circulation. 2022;145(416–423):20220207. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.121.056015.

Kannel WB. Fifty years of Framingham Study contributions to understanding hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1000949.

Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2459–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144.

Lash TL, Vanderweele TJ, Haneuse S, et al. Modern epidemiology, chapter 15: precision and study size. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2021. p. 333–64.

Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Composite end points in randomized trials: there is no free lunch. JAMA. 2010;303:267–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.2017.

Montori VM, Permanyer-Miralda G, Ferreira-González I, et al. Validity of composite end points in clinical trials. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2005;330:594–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7491.594.

Lauer MS, Topol EJ. Clinical trials–multiple treatments, multiple end points, and multiple lessons. JAMA. 2003;289:2575–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.19.2575.

Schmidt M, Sørensen HT, Pedersen L. Diclofenac use and cardiovascular risks: series of nationwide cohort studies. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2018;362(k3426):20180904. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3426.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Danish Library. The Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University Hospital funded the research. The Department receives funding for other studies from companies in the form of research grants to and administered by Aarhus University. None of those studies have any relation to the present study. The Danish National Health Survey was funded by the Capital Region; Region Zealand; the South Denmark Region; the Central Denmark Region; the North Denmark Region; the Ministry of Health, and the National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark.

Conflicts of interest

TLL is a member of the Amgen Methods Council, for which he receives consulting fees and travel support. The remaining contributing authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record number: 2015-57-0002) via Aarhus University (record number: 2016-051-000001).

Consent to participate

According to the Danish legislation, informed consent is not required for studies based solely on registry data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

Codes are available upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

KB, JH, TLL, and MS designed the study. KB, LP, HTS, and MS collected the data. KB performed the analyses. KB, LP, VE, MSG, HTS, JH, TLL, and MS interpreted the data. KB developed the manuscript. LP, VE, MSG, HTS, JH, TLL, and MS critically revised the article’s intellectual content. All authors approve the final version of the article to be published.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonnesen, K., Pedersen, L., Ehrenstein, V. et al. Impact of Lifestyle and Socioeconomic Position on the Association Between Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events: A Case-Crossover Study. Drug Saf 46, 533–543 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-023-01298-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-023-01298-0