Abstract

Introduction

Numerous initiatives over the past decade have targeted the problem of antibiotic overuse in the US; however, the cumulative impact of such initiatives upon recent patterns of use is not known.

Objectives

The aims of this study were to (1) describe general trends in outpatient antibiotic use among adults over the period 2006–2015; and (2) identify rapid shifts in use during this time period as potential indicators for key events.

Methods

This was an observational study set in the ambulatory setting. Patients ≥ 18 years of age were selected from the Optum Clinformatics Datamart™, a commercial insurance claims database. The outcome measures of interest were prescriptions filled/1000 enrolled individuals, by year or quarter. We used linear regression to identify trends in use over multiple years, and change-point regression to identify rapid shifts in use within individual years.

Results

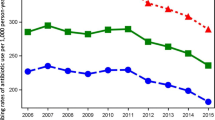

From 2006 to 2015, antibiotic use declined significantly, decreasing by 12% for adults younger than 65 years of age (913–807 prescriptions/1000 individuals, p = 0.0001) and by 5% for adults ≥ 65 years of age (991–943 prescriptions/1000 individuals, p = 0.018). With change-point regression, we identified a number of rapid shifts in the use of specific antibiotic classes, such as downward shifts in the use of quinolones and macrolides during the second quarter of 2008 and 2013, respectively.

Conclusions

Over the period 2006–2015 outpatient use of antibiotics decreased substantially among adults. Rapid shifts in use occurring in 2008 and 2013 may reflect the presence of key drivers of change, such as abrupt changes in access to care or perceived antibiotic safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

McCaig LF, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial drug prescribing among office-based physicians in the United States. JAMA. 1995;273(3):214–9.

Gonzales R, Steiner JF, Sande MA. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis by ambulatory care physicians. JAMA. 1997;278(11):901–4.

Linder JA, Singer DE, Stafford RS. Association between antibiotic prescribing and visit duration in adults with upper respiratory tract infections. Clin Ther. 2003;25(9):2419–30.

Steinman MA, Yang KY, Byron SC, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Variation in outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(12):861–8.

Zhang Y, Steinman MA, Kaplan CM. Geographic variation in outpatient antibiotic prescribing among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1465–71.

Fairlie T, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL, Hicks LA. National trends in visit rates and antibiotic prescribing for adults with acute sinusitis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1513–4.

Hicks LA, Taylor TH Jr, Hunkler RJUS. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing, 2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(15):1461–2.

Suda KJ, Hicks LA, Roberts RM, Hunkler RJ, Taylor TH. Trends and seasonal variation in outpatient antibiotic prescription rates in the United States, 2006–2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(5):2763–6.

Barnett ML, Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with acute bronchitis in the United States, 1996–2010. JAMA. 2014;311(19):2020–2.

Klein EY, Makowsky M, Orlando M, Hatna E, Braykov NP, Laxminarayan R. Influence of provider and urgent care density across different socioeconomic strata on outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the USA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(5):1580–7.

Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, Suda KJ, Hunkler RJ, Taylor TH Jr, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1308–16.

Alsan M, Morden NE, Gottlieb JD, Zhou W, Skinner J. Antibiotic use in cold and flu season and prescribing quality: a retrospective cohort study. Med Care. 2015;53(12):1066–71.

Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among us ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864–73.

Khachatourians GG. Agricultural use of antibiotics and the evolution and transfer of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. CMAJ. 1998;159(9):1129–36.

Davies J, Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74(3):417–33.

Finland M. Emergence of antibiotic resistance in hospitals, 1935–1975. Rev Infect Dis. 1979;1(1):4–22.

Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(11):e280.

Cho I, Blaser MJ. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(4):260–70.

Gonzales R, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for treatment of acute respiratory tract infections in adults: background, specific aims, and methods. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):479–86.

Choosing Wisely, An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. “Antibiotics: When you need them—and when you don’t”. 2014. http://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/antibiotics/. Accessed 3 Nov 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get smart: know when antibiotics work. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/programs-measurement/national-activities/antibiotics-work.html. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2006 patient-level file specifications. 2006. http://www.ncqa.org/portals/0/HEDISQM/DataSubmission/2006PatientLevelHEDISSubmissionSpecifications.pdf. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

US FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA updates warnings for oral and injectable fluoroquinolone antibiotics due to disabling side effects. 2016. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm511530.htm. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

US FDA. Information for Healthcare Professionals: Fluoroquinolone Antimicrobial Drugs [ciprofloxacin (marketed as Cipro and generic ciprofloxacin), ciprofloxacin extended-release (marketed as Cipro XR and Proquin XR), gemifloxacin (marketed as Factive), levofloxacin (marketed as Levaquin), moxifloxacin (marketed as Avelox), norfloxacin (marketed as Noroxin), and ofloxacin (marketed as Floxin)]. 2013. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm126085.htm#. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

US FDA. Telithromycin (marketed as Ketek) Information. 2016. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm107824.htm. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

US FDA. Cleocin HCL (clindamycin hydrochloride) capsules. 2016. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm194129.htm. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

US FDA. Risk of fluoroquinolone-associated Myasthenia Gravis Exacerbation February 2011 Label Changes for Fluoroquinolones. 2011. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm247115.htm. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1881–90.

Lee GC, Reveles KR, Attridge RT, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: 2000–2010. BMC Med. 2014;12:96.

Optum. Clinformatics data mart. 2014. https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/productSheets/Clinformatics_for_Data_Mart.pdf. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

Julious S. Inference and estimation in a changepoint regression problem. Statistician. 2001;50(1):51–61.

Hawkins D. Fitting multiple change-point models to data. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2001;37:323–41.

United States Department of Agriculture, Rocky Mountain Research Station. A tutorial on the piecewise regression approach applied to bedload transport data. 2007. http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr189.pdf. Accessed 19 Dec 2016.

Lopez BJ, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;46:348–55.

Burnham KP, Anderson DR, Huyvaert KP. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: some background, observations, and comparisons. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2011;65:23–35.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–107.

IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. HSRN Data Brief: Xponent™. 2011. https://www.imshealth.com/files/web/IMSH%20Institute/Xponent_Data_Brief_Final-.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

Gahbauer AM, Gonzales ML, Guglielmo BJ. Patterns of antibacterial use and impact of age, race/ethnicity, and geographic region on antibacterial use in an outpatient medicaid cohort. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(7):677–85.

Yaeger JP, Temte JL, Hanrahan LP, Martinez-Donate P. Roles of clinician, patient, and community characteristics in the management of pediatric upper respiratory tract infections. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):529–36.

Coco AS, Horst MA, Gambler AS. Trends in broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing for children with acute otitis media in the United States, 1998–2004. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:41.

Barlam TF, Soria-Saucedo R, Cabral HJ, Kazis LE. Unnecessary antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections: association with care setting and patient demographics. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(1):ofw045.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient Antibiotic Prescriptions—United States. 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/pdfs/annual-reportsummary_2014.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

Blue Cross Blue Shield. Antibiotic prescription fill rates declining in the US. 2017. https://www.bcbs.com/the-health-of-america/reports/antibiotic-prescription-rates-declining-in-the-US. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey [updated 21 Aug 2009; cited 13 Oct 2017]. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp.

Hill SC, Zuvekas SH, Zodet MW. Implications of the accuracy of MEPS prescription drug data for health services research. Inquiry. 2011;48(3):242–59.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(14):332–6.

Supermarket News. “Stop & Shop, Giant Foods Offer Free Antibiotics”. 2008. http://www.supermarketnews.com/latest-news/stop-shop-giant-foods-offer-free-antibiotics. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Coverage in an Economic Downturn: Impact of Tight Budgets on Families and States. 2008. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-in-an-economic-downturn-impact/. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

Medscape. “FDA Approves First Generic Versions of Levofloxacin”. 2011. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/745007. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011–2012 Flu Season Draws to a Close. 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2011-2012-flu-season-wrapup.htm. Accessed 13 Oct 2017.

Riedle BN, Polgreen LA, Cavanaugh JE, Schroeder MC, Polgreen PM. Phantom prescribing: examining the frequency of antimicrobial prescriptions without a patient visit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(3):273–80.

United States Census Bureau. “Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2015”. 2016. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-257.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2018.

European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial consumption database (ESAC-Net). 2017. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/antimicrobial-consumption/surveillance-and-disease-data/database. Accessed 1 Jun 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MLM and EP were primarily responsible for the design of the study and drafting of the manuscript; MLM and JF were responsible for the statistical analyses; KH, MF, AK, and JL contributed to the design/manuscript revision; and JL performed extracts of the data from the Optum database.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R01HS024930 (MAF and JAL) and HHSP233201500020I (JAL). Dr. Kesselheim’s work in this area is supported by CeBIL (Collaborative Research Program for Biomedical Innovation Law), a scientifically independent collaborative research program supported by a Novo Nordisk Foundation Grant (NNF17SA0027784). Dr. Patorno was supported by a career development Grant (K08AG055670) from the National Institute on Aging.

Conflict of interest

Mallika L. Mundkur, Jessica Franklin, Krista Huybrechts, Michael A. Fischer, Aaron S. Kesselheim, Jeffrey A. Linder, Joan Landon, and Elisabetta Patorno have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mundkur, M.L., Franklin, J., Huybrechts, K.F. et al. Changes in Outpatient Use of Antibiotics by Adults in the United States, 2006–2015. Drug Saf 41, 1333–1342 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-018-0697-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-018-0697-4