Abstract

Introduction

Free prescription drug samples provided in physician offices can lead to exposure misclassification in pharmacoepidemiologic studies that rely on pharmacy claims data.

Methods

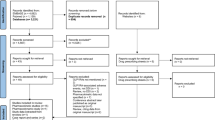

We quantified drug-specific sample provision rates based on nationally projected data from a survey of over 3200 US office-based physicians for 1993–2013.

Results

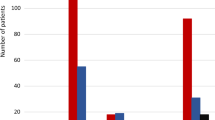

Between 2009 and 2013, a total of 44.7 % of newly initiated brand-only sitagliptin but only 3.6 % of generically available metformin therapy was provided as samples. We observed similar discrepancies between newly initiated rosuvastatin and simvastatin, dabigatran and warfarin, atomoxetine and methylphenidate, and between oral antibiotic drugs. During continued therapy, sample use was still present though to a lesser extent (sitagliptin 17.0 %, rosuvastatin 23.9 %), and remained high for some oral contraceptives (norethindrone 55.8 %). Oral contraceptives had the longest average days of sample supply (levonorgestrel, continued use 85.1 days). The average days of supply for all other chronically used study drugs ranged from 13.4 (dabigatran, new use) to 25.3 (exenatide, continued use) per sample provided. From 1993 to 2013, we found pronounced drops in sample provisions over time coinciding with more recent generic approval dates.

Conclusions

We observed markedly differential exposure to medication samples between branded and generic drugs. This can introduce bias in pharmacoepidemiologic studies, especially when adverse events that occur soon after drug initiation are of interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Choudhry NK, Shrank WH. Four-dollar generics–increased accessibility, impaired quality assurance. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1885–7.

Chimonas S, Kassirer JP. No more free drug samples? PLoS Med. 2009;6(5):e1000074.

Vincent WR, Wiesner AM, Steinke DT. “Free” prescription drug samples are not free. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1348–9.

Alexander GC, Zhang J, Basu A. Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46(4):394–402.

Chew LD, O’Young TS, Hazlet TK, Bradley KA, Maynard C, Lessler DS. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):478–83.

Hartung DM, Evans D, Haxby DG, Kraemer DF, Andeen G, Fagnan LJ. Effect of drug sample removal on prescribing in a family practice clinic. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(5):402–9.

Miller DP, Mansfield RJ, Woods JB, Wofford JL, Moran WP. The impact of drug samples on prescribing to the uninsured. South Med J. 2008;101(9):888–93.

Westfall JM, McCabe J, Nicholas RA. Personal use of drug samples by physicians and office staff. JAMA. 1997;278(2):141–3.

Mabins MN, Emptage RE, Giannamore MR, Hall LE. Drug sample provision and its effect on continuous drug therapy in an indigent care setting. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;47(3):366–72.

Hurley MP, Stafford RS, Lane AT. Characterizing the relationship between free drug samples and prescription patterns for acne vulgaris and rosacea. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(5):487–93.

Cutrona SL, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, Bor DH, McCormick D, Himmelstein DU. Characteristics of recipients of free prescription drug samples: a nationally representative analysis. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):284–9.

Tjia J, Briesacher BA, Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Medicare beneficiaries and free prescription drug samples: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):709–14.

Johnsson Funk M, Landi NL. Misclassification in administrative claims data: quantifying the impact of treatment effect estimates. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2014;2014(1):175–85.

Jacobus S, Schneeweiss S, Chan KA. Exposure misclassification as a result of free sample drug utilization in automated claims databases and its effect on a pharmacoepidemiology study of selective COX-2 inhibitors. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(10):695–702.

Gellad WF, Huskamp HA, Li A, Zhang Y, Safran DG, Donohue JM. Use of prescription drug samples and patient assistance programs, and the role of doctor-patient communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1458–64.

Lauffenburger JC, Balasubramanian A, Farley JF, Critchlow CW, O’Malley CD, Roth MT, et al. Completeness of prescription information in US commercial claims databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(8):899–906.

Li X, Sturmer T, Brookhart MA. Evidence of sample use among new users of statins: implications for pharmacoepidemiology. Med Care. 2014;52(9):773–80.

Vigamox label. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/021598s017lbl.pdf. [Accessed 21 Nov 2014].

Avelox label. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021085s057,021277s054lbl.pdf. [Accessed 20 Nov 2014].

Guess HA. Behavior of the exposure odds ratio in a case-control study when the hazard function is not constant over time. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(12):1179–84.

Gamble JM, McAlister FA, Johnson JA, Eurich DT. Quantifying the impact of drug exposure misclassification due to restrictive drug coverage in administrative databases: a simulation cohort study. Value Health. 2012;15(1):191–7.

Zocor label. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/019766s091lbl.pdf. [Accessed 20 Nov 2014].

Yaz label. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/021676s012lbl.pdf. [Accessed 20 Nov 2014].

Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–20.

Moride Y, Abenhaim L. Evidence of the depletion of susceptibles effect in non-experimental pharmacoepidemiologic research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(7):731–7.

Lewis JD, Ferrara A, Peng T, Hedderson M, Bilker WB, Quesenberry CP Jr, et al. Risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients treated with pioglitazone: interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):916–22.

Food and Drug Administration. Drug safety communication: ongoing safety review of actos (pioglitazone) and potential increased risk of bladder cancer after two years exposure. September 17, 2010. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm226214.htm. [Accessed 21 Nov 2014].

Hampp C, Borders-Hemphill V, Moeny DG, Wysowski DK. Use of antidiabetic drugs in the US, 2003–2012. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(5):1367–74.

Cutrona SL, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU, Shrank WH, et al. Free drug samples in the United States: characteristics of pediatric recipients and safety concerns. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):736–42.

Disclaimer

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the US FDA or the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Conflict of interest

Christian Hampp, Patty Greene, and Simone Pinheiro have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study

Ethical standards

The study was exempted from review by the FDA Research Involving Human Subjects (RIHSC) committee under 45 CFR 46 101(b)(4).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hampp, C., Greene, P. & Pinheiro, S.P. Use of Prescription Drug Samples in the USA: A Descriptive Study with Considerations for Pharmacoepidemiology. Drug Saf 39, 261–270 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0382-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0382-9