Abstract

Introduction

It has been suggested that doctors in their first year of post-graduate training make a disproportionate number of prescribing errors.

Objective

This study aimed to compare the prevalence of prescribing errors made by first-year post-graduate doctors with that of errors by senior doctors and non-medical prescribers and to investigate the predictors of potentially serious prescribing errors.

Methods

Pharmacists in 20 hospitals over 7 prospectively selected days collected data on the number of medication orders checked, the grade of prescriber and details of any prescribing errors. Logistic regression models (adjusted for clustering by hospital) identified factors predicting the likelihood of prescribing erroneously and the severity of prescribing errors.

Results

Pharmacists reviewed 26,019 patients and 124,260 medication orders; 11,235 prescribing errors were detected in 10,986 orders. The mean error rate was 8.8 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 8.6–9.1) errors per 100 medication orders. Rates of errors for all doctors in training were significantly higher than rates for medical consultants. Doctors who were 1 year (odds ratio [OR] 2.13; 95 % CI 1.80–2.52) or 2 years in training (OR 2.23; 95 % CI 1.89–2.65) were more than twice as likely to prescribe erroneously. Prescribing errors were 70 % (OR 1.70; 95 % CI 1.61–1.80) more likely to occur at the time of hospital admission than when medication orders were issued during the hospital stay. No significant differences in severity of error were observed between grades of prescriber. Potentially serious errors were more likely to be associated with prescriptions for parenteral administration, especially for cardiovascular or endocrine disorders.

Conclusion

The problem of prescribing errors in hospitals is substantial and not solely a problem of the most junior medical prescribers, particularly for those errors most likely to cause significant patient harm. Interventions are needed to target these high-risk errors by all grades of staff and hence improve patient safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Foundation year 1 and year 2 doctors were both more than twice as likely to prescribe erroneously when compared against medical consultant error rates. |

No significant differences in severity of error were observed between grades of prescriber. |

Interventions are needed for all grades of staff, not just junior doctors, to reduce potentially serious prescribing errors. |

1 Introduction

Improving patient safety in healthcare settings is a major concern globally [1]. Medicines are the most commonly used clinical intervention in healthcare, and errors involving the prescribing, dispensing, administration and monitoring steps of medication use are common [2–4]. Such medication errors can prolong hospital stay and lead to significant patient morbidity and even death [5, 6]. Each year in England alone, the cost of preventable harm from medicines has been estimated at £750 million [7].

Prescribing errors in hospitals are particularly common; our systematic review of 65 studies, which used a variety of data collection methods, found a median prescribing error rate of 7 % (interquartile range [IQR] 2–14) per medication order, 52 errors (IQR 8–227) per 100 hospital admissions and 24 (IQR 6–216) per 1000 patient days [2]. Error severity was assessed in 74 % of studies, but comparison between studies was impossible due to the disparity of assessment methods used. Most previous studies were also conducted in only one or two hospitals. Two recent studies conducted in up to nine hospitals in Britain found that 10.9 and 7.5 % of medication items were prescribed incorrectly [8, 9]. Errors have been presumed to be made more commonly by junior doctors, particularly those in their first year after graduating from university [10]. The PROTECT study [9] found that doctors who were in their first and second years of training made more errors than did consultants (7.4 and 8.6 vs. 6.3 %), but Seden et al. [8] found no difference between error rates of different grades of doctor.

Severity of errors has been measured in a variety of ways in published studies, making direct comparison between studies impossible in our systematic review [2]. Recent work has suggested there was no association between grades of doctors and the proportion of errors categorised as significant or higher [8] when correcting for types of prescription and ward speciality. However, whether other factors such as type of drug or route of administration affect the risk of harm to patients is not known.

This study aimed to identify the prevalence of prescribing errors made by junior doctors compared with those made by their senior colleagues and other non-medical prescribers and to investigate predictors of the potentially serious prescribing errors they made.

2 Methods

This large prospective study was undertaken in 20 UK National Health Service (NHS) hospitals located across the north-west of England, with data being collected over 7 selected weekdays, each approximately 1 month apart. Three of the hospitals used electronic prescribing at some or all stages of a patient’s admission. We used an established definition of a prescribing error as “one which occurs when, as a result of a prescribing decision or prescription-writing process, there is an unintended, significant reduction in the probability of treatment being timely and effective, or increase in the risk of harm when compared with generally accepted practice” [11]. The definition has been extensively used in previous studies [2, 8, 9] and is accompanied by lists of situations that should be included and excluded as prescribing errors.

Lead pharmacists from each of the hospitals involved in the study attended two training events, each followed by a question and answer session conducted by DMA and PJL. The lead pharmacists subsequently provided training on data collection at their hospitals to all pharmacists participating in the study, supported by an information booklet providing detailed information on definitions and study requirements. At the study hospitals, inpatient medication orders were written by prescribers (or rewritten when required) directly onto a combined prescription and nursing administration chart, known as ‘the drug chart’ (normal UK practice). Hospital pharmacists screened all newly prescribed or rewritten inpatient medication orders for prescribing errors as part of their routine pharmacy practice. Data collection occurred between 08:30 and 17:00, Monday to Friday, but included a review of prescriptions written outside these hours. In the UK, ward-based clinical pharmacists routinely check inpatient prescriptions at, or soon after, patient admission, when medicines reconciliation is undertaken. Errors identified at hospital admission may include incorrectly ascertaining and prescribing patients’ usual long-term medication. Inpatient drug charts are routinely checked at least daily during weekdays by ward-based clinical pharmacists. Discharge prescriptions are also checked and authorised by a pharmacist prior to supply of medication. Electronic prescription orders could be checked either on the hospital wards or in the hospital pharmacy. Pharmacists may amend or clarify some aspects of prescribing or discuss with the clinical team any recommendations or safety issues at these points of care.

Data were collected on the number of medication orders checked, the grade and type of prescriber (Table 1), the stage of admission when prescribed (on admission, newly prescribed or rewritten during the stay or at discharge) and the number and nature of any prescribing errors. Medications involved in errors were categorised according to the relevant chapter in the British National Formulary (BNF) [12].

2.1 Error Validation

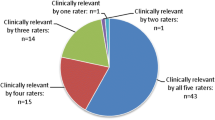

Two validation panels were formed, both comprising two hospital clinicians and two pharmacists, and both of them met on several occasions to assess prescribing errors reported by pharmacists. The panels verified that each report represented a genuine prescribing error, categorised the type of error that it represented and judged its perceived severity. Panel members discussed each error until consensus was achieved. Severity categories included minor, significant, serious, or potentially lethal errors and were based on rating scales used in previous medication error research [13, 14]. Additional details about the severity classification scheme are provided in the appendix available in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

2.2 Data Analysis

The denominator for calculating the prescribing error rate was the number of newly written regular, ‘when required’ and discharge medication orders screened by hospital pharmacists, including any medication orders omitted [15]. All confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated at 95 %.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were developed to examine the potential impact of the following variables on the likelihood of a prescribing error: type of prescriber, type of prescription (handwritten vs. electronic), and the stage of hospital stay at which the medication order was issued. Multinomial logistic regression models identified factors predicting the severity of a prescribing error, particularly which factors were associated with a significant or potentially serious error rather than a minor error. All regression models were also adjusted for clustering by hospital site.

3 Results

Over the 7 days of data collection, 26,019 patients and 124,260 medication orders were reviewed by pharmacists. Of these, 10,986 medication orders had prescribing errors, resulting in 11,235 prescribing errors being detected. The mean prescribing error rate was 8.8 % (95 % CI 8.6–9.1) errors per 100 medication orders. Prescribing error rates presented by type of prescriber and stage of hospital stay are shown in Table 2.

When expressed by the stage of hospital stay, the error rate associated with medication orders at the time of hospital admission (13.3 %, 95 % CI 12.8–13.8) was higher than when newly prescribed medication was initiated during the hospital stay (7.5 %, 95 % CI 7.1–7.9) or when medication was prescribed on discharge from hospital (6.3 %, 95 % CI 5.9–6.7). Foundation doctors (FY1 and FY2) wrote the majority of medication orders (68 %) and had the highest prescribing error rates (FY1 8.6 %, 95 % CI 8.2–8.9; FY2 10.2 %, 95 % CI 9.7–10.7) in comparison with other types of prescriber.

3.1 Types of Prescribing Errors, Drug Classes Involved and Severity of Errors

Omission of required drug therapy at the time of hospital admission was by far the most common type of error, occurring almost three times as frequently as the next most numerous type of error, and accounting for 28.5 % of all prescribing errors (Table 3). Under-dosage (10.9 %) and over-dosage (8.4 %) of medication were the next most common error types. Almost half of the errors related to the need for drug therapy (43.5 %), 5.2 % related to selection of a specific drug, 23.5 % related to selection of a dosage regimen, 12.9 % related to administration of a drug, and 14.9 % related to providing a drug product.

Cardiovascular, central nervous system, respiratory, endocrine, and gastrointestinal drugs were the five most common therapeutic categories associated with prescribing errors, accounting for 73.1 % of all medications involved in errors. Severity grading found that 41.1 % of prescribing errors were minor, 51.6 % were significant and the remaining 7.3 % were serious or potentially life threatening. The rate of potentially serious prescribing errors was higher for consultants and nurse prescribers than all other types of prescriber, as shown in Table 4.

3.2 Predictors of Likelihood of Prescribing Error

After controlling for the type of prescriber, prescribing stage and type of prescription, significant differences were observed for all three explanatory variables (Table 5). The multivariable model indicated there were significantly higher rates of prescribing errors for all types of prescriber when compared against consultant prescribing error rates, with FY1 (odds ratio [OR] 2.13; 95 % CI 1.80–2.52) and FY2 (OR 2.23; 95 % CI 1.89–2.65) doctors being more than twice as likely to prescribe erroneously as consultants. No significant differences were identified for prescribing error rates for pharmacists (OR 0.84; 95 % CI 0.36–1.93) or nurse prescribers (OR 1.00; 95 % CI 0.71–1.39) when compared against consultant prescribing error rates.

Likewise, the stage of hospital stay was also found to be an important predictor of the likelihood of prescribing errors after controlling for the type of prescriber and the type of prescription. Medication orders issued at the time of hospital admission were 70 % more likely to be associated with a prescribing error (OR 1.70; 95 % CI 1.61–1.80) than those issued during the hospital stay. In contrast, prescribing errors were 52 % less likely (OR 0.48; 95 % CI 0.43–0.52) on drug charts that were rewritten and 23 % less likely on discharge prescriptions (OR 0.77; 95 % CI 0.72–0.82) than medication orders issued during the hospital stay. Electronic prescriptions were 12 % less likely to be associated with a prescribing error than were handwritten prescriptions (OR 0.88; 95 % CI 0.79–0.97) after controlling for type of prescriber and the prescribing stage at which the medication order was issued.

3.3 Predictors of Severity of Prescribing Error

There were no significant differences in severity of error in the multinomial logistic regression model between types of prescriber or whether the medication order was handwritten or generated electronically (Table 6). Potentially serious prescribing errors were significantly less likely to occur on admission (OR 0.46; 95 % CI 0.33–0.66) or when a drug chart was rewritten (OR 0.62; 95 % CI 0.39–0.98) compared with when a medication order was issued during the hospital stay.

Potentially serious prescribing errors were significantly more likely to be associated with cardiovascular (OR 11.96; 95 % CI 7.92–18.06), central nervous system (OR 6.69; 95 % CI 4.21–10.64), anti-infective (OR 5.48; 95 % CI 3.43–8.76), endocrine (OR 16.48; 95 % CI 10.27–26.46), and musculoskeletal and joint disease drugs (OR 6.95; 95 % CI 4.21–11.49) than gastrointestinal drugs. Parenteral routes of drug administration (intravenous/intramuscular/subcutaneous) were also three times more likely (OR 3.66; 95 % CI 2.98–4.49) to be associated with serious (rather than minor) prescribing errors than was the oral route of drug administration.

Table 7 presents the results from a multinomial logistic regression with interaction terms to explore whether the effect of therapeutic drug group on error severity differed by the route of administration, adjusting for the factors shown in Table 5 to be associated with prescribing error severity. There was a 28-fold increase in the odds of a serious prescribing error rather than minor for gastrointestinal drugs administered parenterally compared with medication orders from the same therapeutic group that were not injected (OR 28.63; 95 % CI 10.59–77.45). For all other therapeutic drug groups, all routes of administration had increased odds of serious errors compared with gastrointestinal drugs, and the odds for potentially serious errors were consistently higher for parenteral medication orders.

4 Discussion

The problem of prescribing errors in hospitals is substantial and not solely, or even primarily, a problem of the most junior medical prescribers. In this large prospective study in 20 NHS hospitals, prescribing errors occurred in 8.8 % of newly prescribed medication orders, occurring more commonly at hospital admission and on hand-written orders than in those generated electronically. Doctors of all grades made prescribing errors, as did non-medical prescribers, but FY1 and FY2 doctors were more than twice as likely to make prescribing errors as consultant doctors. However, they were not more likely to make serious errors than were more senior medical doctors.

This study was not without limitations. The errors were identified by pharmacists as part of their routine work, a common method of prescribing error data collection [8, 9, 16]. Failure either to identify or to record errors would result in our data underestimating the actual error rate. Data were recorded on 1 day per month to reduce the impact of such data collection fatigue. Multiple pharmacists were involved, leading to potential variations in data collection practice, even with training. To minimise the impact, all errors recorded were reviewed by a validation panel, although we recognised this could not address variations where errors were not identified or recorded. Identification of the author of handwritten prescriptions is known to be challenging [17], and the grade of the prescriber was not recorded for 11 % of the medication orders in our study. The impact of misidentification was minimised by having the regular pharmacists, who were familiar with the signatures of the regular doctors, collect the data. Nonetheless, pharmacists only recorded the grade of the doctors writing the prescription, rather than any other doctors involved in making the prescribing decisions. Senior doctors often instruct juniors on ward rounds as to what to write [18, 19], and the error rate described here for senior doctors could be an underestimate as to the erroneous prescribing with which they were involved.

As with other recent British studies [8, 9], we have found that prescribing errors are made by all grades of doctors, not just those in their first year of post-graduate training. Deficiencies in undergraduate medical education can therefore only be part of the cause [20], and changes to it, at best, only part of the solution. If education is to be a means of reducing errors, it must include higher specialist training and the continuing professional development of all prescribers as well as education during the undergraduate years and foundation training. Recent medical education research has identified the importance of minimising the negative effects of transitions [21]. In particular, it is well recognised that an important transition occurs between being an undergraduate student and being an early career practitioner, and it has been consistently shown that ‘becoming a prescriber for real’ is one of its most dominant, and negative, features [22, 23].

Trainees’ lack of experience in completing prescriptions before they start work is a well-recognised problem [24], as is the inappropriate satisfaction of some of them with writing a prescription that ‘looks about right’ [25]. Although trainees in other studies have indicated that they want more practical teaching [26], during undergraduate education, at least, they needed the pressure of a summative assessment to motivate them to take it up [27]. In the UK, the General Medical Council (GMC) revised their core guidance for medical education, Tomorrow’s Doctors, to recommend that formal prescribing skills training and practical experience in the NHS be provided for medical students [28]. Alongside this, a new national assessment of prescribing competence has also been introduced for all medical students in the UK before they graduate from medical school [29]. It will be important to evaluate the impact of these recent developments on prescribing errors to determine whether they lead to recognisable improvements in patient safety. A study that explored junior doctors’ experiences and responses to error found that learning was maximised when errors were formally discussed and constructive feedback was given [30], although Teunissen et al. [31] have shown that trainees’ openness to negative feedback depends on whether their primary motivation is to be seen to be competent, or to learn from their mistakes.

Over half the errors found in this study were considered significant with the potential to cause some form of patient harm, similar to that found elsewhere [8], with a further 7.3 % rated potentially serious or life threatening. Serious prescribing errors were far more likely to occur during a patient’s hospital stay and when prescribing medication to be administered parenterally. These findings present important early targets for future interventions. Key questions are how and why these errors occur. The quantitative analysis reported here was part of a large mixed-methods study (EQUIP project) in which we also interviewed 30 FY1 doctors about the causes of their prescribing errors, and we draw on this work to interpret our findings [32]. Complex systems were often involved in causing errors, many of which related to the healthcare environment within which doctors worked, including the impact of busy and stressful working environments or unfamiliarity of the system in which the doctor was working. We found that the FY1 doctors often lacked contextual, rather than basic, knowledge and had difficulty framing clinical problems rather than necessarily lacking specific drug knowledge. Prescribing errors were often found to be due to multiple problems, with several active failures and error-provoking conditions acting together to result in errors. Given this, solutions aimed at a single cause of error are likely to have only limited impact, and multi-factorial interventions addressing many parts of the process of prescribing are likely to be needed [33].

The literature on causes of prescribing errors is relatively sparse [33], and the qualitative research previously conducted mainly concentrates on prescribing by junior doctors, usually in the first year of their training. Much less is known about the causes of prescribing errors by doctors further into their training, such as FY2 doctors, and no work has been conducted focusing on causes of errors made by senior doctors or non-medical prescribers, although this study shows that they occur. More needs to be understood about errors made by senior doctors to inform the necessary continuing professional development delivery and systems redesign that is needed to improve patient safety.

Although we found that prescribing errors were 12 % less likely to occur with electronic prescribing systems, we found no difference in the likelihood of serious prescribing errors occurring between hand-written and electronically generated medication orders. This supports the findings from a systematic review of 12 studies that reported computerised provider order-entry systems can reduce minor prescribing errors, with some studies suggesting increasing rates of some more serious errors, such as duplicating orders or failure to discontinue medicines no longer needed [34].

The stage of the patient’s hospital stay during which errors, particularly significant errors, were more likely to occur was at the point of admission and, at that stage, failure to prescribe pre-admission medication was the most common error. There is evidence that conducting medicines reconciliations as soon as possible after admission will reduce omission of long-term medicines [35–37]. Medicines reconciliation is the process by which an up-to-date and accurate list of medicines is created at transitions of care, using information collected from multiple sources as to the pre-admission medication, checked with the current prescribed medicines, and any discrepancies communicated in writing with the current care team [38]. Our findings support the need for medication reconciliations to improve medication safety at transition points between healthcare settings.

5 Conclusion

This study found that junior doctors were twice as likely as senior doctors to make prescribing errors, but that they had similar rates of potentially serious prescribing errors. Potentially serious errors were more likely to be associated with prescriptions for parenteral administration, especially for cardiovascular or endocrine disorders. Further research is needed to target interventions to reduce these high-risk errors and to improve patient safety.

References

World Health Organization. World Alliance for Patient Safety. [cited 2015 Jan 6]; Available from: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/worldalliance/en/.

Lewis PJ, Dornan T, Taylor D, Tully MP, Wass V, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence, incidence and nature of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients. A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32:379–89.

James KL, Barlow D, McArtney R, Hiom S, Roberts D, Whittlesea C. Incidence, type and causes of dispensing errors: a review of the literature. Int J Pharm Pract. 2009;17(1):9–30.

Keers RN, Williams SD, Cooke J, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence and nature of medication administration errors in health care settings: a systematic review of direct observational evidence. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(2):237–56.

Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277:301–6.

Phillips DP, Christenfeld N, Glynn LM. Increase in US medication-error deaths between 1983 and 1993. Lancet. 1998;351(9103):643–4.

NPSA. Patient Safety Observatory Report 4: Safety in doses. [cited 2015 Jan 6]; Available from: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59822&p=14.

Seden K, Kirkham JJ, Kennedy T, Lloyd M, James S, McManus A et al. Cross-sectional study of prescribing errors in patients admitted to nine hospitals across North West England. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1).

Ryan C, Ross S, Davey P, Duncan EM, Francis JJ, Fielding S, et al. Prevalence and causes of prescribing errors: the prescribing outcomes for trainee doctors engaged in clinical training (PROTECT) Study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e79802.

Ross S, Loke YK. Do educational interventions improve prescribing by medical students and junior doctors? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):662–70.

Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M. What is a prescribing error? Qual Health Care. 2000;9:232–7.

Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2014.

Folli HL, Poole RL, Benitz WE. Medication error prevention by clinical pharmacists in two children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 1987;79:718–22.

Lesar TS, Lomaestro BM, Pohl H. Medication-prescribing errors in a teaching hospital. A 9-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1569–76.

Allan EL, Barker KN. Fundamentals of medication error research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1990;47(3):555–71.

Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: their incidence and clinical significance. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(4):340–4.

Reynolds M, Jheeta S, Franklin BD. A plan-do-study-act approach to increasing the prevalence of prescribers’ names on individual inpatient medication orders. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(Supplement 2):95.

Ross S, Hamilton L, Ryan C, Bond C. Who makes prescribing decisions in hospital inpatients? An observational study. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88:507–10.

Nichols P, Copeland TS, Craib IA, Hopkins P, Bruce DG. Learning from error: identifying contributory causes of medication errors in an Australian hospital. Med J Aust. 2008;188(5):276–9.

Maxwell SR, Cascorbi I, Orme M, Webb DJ. Educating European (junior) doctors for safe prescribing. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;101(6):395–400.

Shacklady J, Holmes E, Mason G, Davies I, Dornan T. Maturity and medical students’ ease of transition into the clinical environment. Med Teach. 2009;31(7):621–6.

Prince K, van de Wiel M, van der Vleuten C, Boshuizen H, Scherpbier A. Junior doctors’ opinions about the transition from medical school to clinical practice: a change of environment. Educ Health. 2004;17:323–31.

Wall D, Bolshaw A, Carolan J. From undergraduate medical education to pre-registration house officer year: how prepared are students? Med Teach. 2006;28(5):435–9.

Han WH, Maxwell SR. Are medical students adequately trained to prescribe at the point of graduation? Views of first year foundation doctors. Scot Med J. 2006;51(4):27–32.

Dobrzanski S, Hammond I, Khan G, Holdsworth H. The nature of hospital prescribing errors. Br J Clin Gov. 2002;7(3):187–93.

Tobaiqy M, McLay J, Ross S. Foundation year 1 doctors and clinical pharmacology and therapeutics teaching. A retrospective view in light of experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(3):363–72.

Scobie SD, Lawson M, Cavell G, Taylor K, Jackson SH, Roberts TE. Meeting the challenge of prescribing and administering medicines safely: structured teaching and assessment for final year medical students. Med Educ. 2003;37(5):434–7.

General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors. Recommendations on undergraduate medical education. 2nd ed. Manchester: General Medical Council; 2009.

MSC Assessment, British Pharmacological Society. Prescribing Skills Assessment. [cited 2015 Jan 6]; Available from: http://www.prescribe.ac.uk/psa/.

Kroll L, Singleton A, Collier J, Rees J. I. Learning not to take it seriously: junior doctors’ accounts of error. Med Educ. 2008;42(10):982–90.

Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, van der Vleuten C, Scherpbier A, Boor K, Scheele F. Who wants feedback? An investigation of the variables influencing residents’ feedback-seeking behavior in relation to night shifts. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):910–7.

Lewis PJ, Ashcroft DM, Dornan T, Taylor D, Wass V, Tully MP. Exploring the causes of junior doctors’ prescribing mistakes: a qualitative study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(2):310–9.

Tully MP, Ashcroft DM, Dornan T, Lewis PJ, Taylor D, Wass V. The causes of and factors associated with prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32(10):819–36.

Reckmann M, Westbrook JI, Koh Y, Lo C, Day RO. Does computerized provider order entry reduce prescribing errors for hospital inpatients? A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):613–23.

Mills PR, McGuffie AC. Formal medicine reconciliation within the emergency department reduces the medication error rates for emergency admissions. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(12):915.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, National Patient Safety Agency. Technical patient safety solutions for medicines reconciliation on admission of adults to hospital. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2007.

Richards M, Ashiru-Oredope D, Chee N. What errors can be identified by pharmacy-led medicines reconciliation? A prospective study. Acute Med. 2011;10(1):2011–21.

National Prescribing Centre. Medicines reconciliation: a guide to implementation. Liverpool: National Prescribing Centre; 2007.

Acknowledgments

The EQUIP team would like to thank the following people: Members of the Expert Reference Group (Graham Buckley, Gary Cook, Dianne Parker, Lesley Pugsley and Mike Scott); Members of the Error Validation Group (Lindsay Harper, Katy Mellor, Steven Williams, Keith Harkins, Steve McGlynn, Ray George, Tim Dornan, Penny Lewis); Tribal Consulting Ltd. (Heather Heathfield, Emma Carter) for database design; Study co-ordinators at hospitals (Linda Aldred, Deborah Armstrong, Isam Badhawi, Kathryn Ball, Neil Caldwell, Vanya Fidling, Nicholas Fong, Heather Ford, Andrea Gill, Lindsay Harper, Jean Holmes, Sally James, Christopher Poole, Sally Shaw, Heather Smith, Julie Street, Atia Rifat, David Thornton, Tracey Thornton, Jane Warren, Steven Williams), and all pharmacists at the study sites who collected data for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the General Medical Council (GMC). The study funders had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of this manuscript or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflict of interest

Darren Ashcroft, Penny Lewis, Mary Tully, Tracey Farragher, David Taylor, Valerie Wass, Steven Williams and Tim Dornan have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Ethical approval

North Manchester NHS Research Ethics Committee.

Additional information

On behalf of the EQUIP study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ashcroft, D.M., Lewis, P.J., Tully, M.P. et al. Prevalence, Nature, Severity and Risk Factors for Prescribing Errors in Hospital Inpatients: Prospective Study in 20 UK Hospitals. Drug Saf 38, 833–843 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0320-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0320-x