Abstract

Treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS) will affect about one in three patients with schizophrenia. Clozapine is the only treatment approved for TRS, and patients should be treated as soon as possible to improve their chances of achieving remission. Despite its effectiveness, concern over side effects, monitoring requirements, and inexperience with prescribing often result in long delays that can expose patients to unnecessary risks and compromise their chances of achieving favorable long-term outcomes. We critically reviewed the literature on clozapine use in TRS, focusing on guidelines, systematic reviews, and algorithms to identify strategies for improving clozapine safety and tolerability. Based on this, we have provided an overview of strategies to support early initiation of clozapine in patients with TRS based on the latest evidence and our clinical experience, and have summarized the key elements in a practical, evidence-based checklist for identifying and managing patients with TRS, with the aim of increasing confidence in prescribing and monitoring clozapine therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Early and sustained treatment with clozapine represents the best available strategy for achieving and maintaining remission in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. |

Common side effects including sialorrhea, constipation and weight gain may result in poor adherence to treatment, while the existence of rare severe adverse events and the associated monitoring burden may result in delays in starting therapy. |

Strategies for optimizing treatment and managing side effects are summarized and a checklist is provided. |

1 Introduction

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness involving positive and negative symptoms, as well as cognitive impairment [1]. It has a median incidence of 287 (uncertainty interval 246–331)/100,000 [2] and median standardized mortality ratio of 2.6 [3]. Therapies targeting postsynaptic dopamine receptors are not effective in all cases, especially regarding negative symptoms and in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS). TRS is defined as patients who do not respond sufficiently to sequential trials of at least two different antipsychotics administered at appropriate doses, duration, and with adequate adherence from the patient [4,5,6,7].

TRS is a major clinical challenge that can occur early in the treatment pathway or develop later in patients who respond initially to antipsychotic treatment [8,9,10]. Several lines of evidence indicate that it has a different neurobiology to schizophrenia that responds to dopamine D2 receptor blockers [11, 12]. It has been hypothesized that TRS could represent a neurobiologically distinct sub-type of schizophrenia [13, 14]. Some data point to a sub-type of schizophrenia associated with TRS characterized by unaltered dopamine function [15,16,17], and glutamate dysregulation [18,19,20], which would explain why these patients do not respond to dopamine D2 blockers [21]. TRS occurs in 20–50% of patients with schizophrenia [22,23,24], including in community settings [25]. It is associated with higher disease burden [26, 27] and poorer outcomes [28], especially involving persistent positive symptoms despite adherence with treatment [29].

Clozapine is the only drug approved for TRS by regulators in North America, Europe, and many other jurisdictions. It is a tricyclic dibenzodiazepine derivative that interacts with multiple neuroreceptors, including dopamine, serotonin and muscarinic receptors [30, 31]. Its low affinity for D2 dopamine receptors may explain its relative lack of extrapyramidal side effects [30], whilst its actions to modulate glutamate levels may contribute to its superior efficacy in TRS [32]. Clozapine is more effective than other antipsychotics for TRS [33], and it reduces rates of hospital readmission and all-cause mortality [34,35,36]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term studies (median follow-up 5.4 years) revealed that continuous clozapine treatment was associated with a significantly lower all-cause mortality rate compared to other antipsychotics (mortality rate ratio = 0.56, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.36–0.85, P = 0.007) [37], which may be due to reduced suicidality [38].

Real-world evidence has confirmed its effectiveness [39,40,41]. Meta-analysis of cohort studies found that clozapine resulted in greater symptom improvement compared to other second-generation antipsychotics, fewer treatment discontinuations, and a lower risk of hospitalization [42]. Based on evidence from nearly 50,000 patients, the risk ratio for hospitalization in patients taking clozapine relative to patients taking other antipsychotics was 0.817 (95% CI 0.725–0.920; P = 0.001) [42].

A systematic review of evidence-based guidelines for antipsychotic treatment of patients with schizophrenia found that all 17 of the guidelines reviewed recommend initiating treatment with the antipsychotic drug clozapine when patients are diagnosed with TRS [43].

However, despite this strong recommendation, clozapine is underutilized in this setting [44,45,46], and many patients initiate clozapine treatment after delays associated with trials of antipsychotic polypharmacy [27, 47, 48]. This may be due to the side-effect profile of clozapine, the monitoring requirements associated with its use, and a lack of prescribing experience [49, 50]. A systematic review that investigated facilitators of guideline adherence in treating TRS identified institutional directives/audits, integrated clozapine clinics, facilitated monitoring, interaction with experts, educational programs, and distribution of educational material as effective strategies for increasing access to clozapine [51]. Delaying initiation of clozapine treatment is associated with higher economic burden [52], and poorer response rates [53,54,55,56].

It may be possible to detect or predict TRS at the first psychotic episode [57,58,59,60]; however, because of the associated risk of potentially serious adverse effects [61], clozapine is not generally indicated in the first-line treatment of schizophrenia [62, 63]. Moreover, patients receiving clozapine are recommended to have hematological monitoring, particularly in the first 6 months of treatment when the risk of agranulocytosis is highest [64]. Clinicians should also be alert for possible cardiovascular, metabolic, gastrointestinal, and neurological adverse effects, some of which may be managed by reducing the dose or titration rate while monitoring frequently [65].

The objective of this review is to provide an overview and guide for clinicians and researchers on clozapine initiation, and to propose a practical checklist for patient selection, clozapine initiation (titration) and maintenance, side-effect monitoring and management, with the aid to facilitate appropriate clozapine use in clinical care.

2 Literature Search

In conducting this review, we have searched Medline using the query (((algorithm OR checklist OR tool OR recommendation OR guide* OR policy)) AND ((review OR systematic OR meta-analysis OR metaanalysis))) AND ((clozapine AND (resistan* OR refractor* OR treatment-resistant schizophrenia OR TRS OR "treatment failure"))) to identify systematic reviews, meta-analyses, guidelines, and treatment algorithms related to TRS published in English before March 2022; we manually searched the reference lists of retrieved recent publications for additional relevant publications.

3 Patient Selection

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications for clozapine include TRS and suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder [62], while the European Medicines Agency (EMA) indication includes TRS and schizophrenia patients who have severe, untreatable neurological adverse reactions to other antipsychotic agents, including second-generation antipsychotics, as well as psychotic disorders occurring during the course of Parkinson's disease, in cases where standard treatment has failed [63], whereas clozapine is indicated only for treating TRS in Australia, Japan, and Canada [66,67,68]. Patient selection should begin by confirming the presence of TRS (Fig. 1) [4], (Fig. 2) [7, 69,70,71], and the absence of contraindications for clozapine treatment, which may differ by country.

(adapted from reference [4], permission not required)

Definition and identification of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. TRS treatment-resistant schizophrenia, CRS clozapine-resistant schizophrenia [7]; BPRS Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, CGI-S-TRS Clinical Global Impressions-Severity TRS Scale, PANSS Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, SANS Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, SAPS Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms

Where available, treatment should take place in a context that supports the psychosocial needs of the patient and provides care for psychiatric comorbidities and any medical problems, as well as providing access to psychiatric pharmacotherapy and monitoring [69,70,71].

3.1 Special Clinical Populations

3.1.1 Pediatric Setting/Early-Onset Schizophrenia

Both the EMA and the FDA state that the safety and effectiveness of clozapine have not been established in pediatric patients [62, 63]; however, guidelines from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [6] and the Canadian guidelines recommend offering clozapine treatment for patients, including children, with early-onset schizophrenia (EOS) meeting criteria for TRS [6, 72]. A systematic review of the efficacy and tolerability of clozapine in this setting revealed that efficacy, tolerability, and dose-blood level relationships are similar to those in adults [73]. Sedation and sialorrhea were reported by most patients treated for EOS. A network meta-analysis established clozapine as more efficacious than other antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia [74].

3.1.2 Older Adults

Few geriatric patients were included in studies that informed the FDA label, therefore, caution is warranted regarding the side effects of tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension in patients with compromised cardiovascular functioning, and anticholinergic effects of constipation and urinary retention in older adults in general [62]. The EMA specifically recommends that treatment be initiated at a low dose and titrated slowly [63]. A systematic review of clozapine use in older adults confirmed the lack of controlled studies and reported modest effectiveness based on observational studies, suggesting that the decision must carefully weigh the potential benefits and risks in each individual patient considering their comorbidities and concomitant treatments [75].

3.1.3 Pregnancy

Clozapine treatment is not contraindicated by the EMA or FDA for pregnant women who clearly require treatment (FDA pregnancy class B) [62, 63]; however, caution and additional monitoring are warranted because of the relative lack of studies. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry does not recommend clozapine treatment during pregnancy because its side-effect profile includes agranulocytosis, metabolic effects, and seizures [76]. A systematic review of outcomes after clozapine continuation in pregnancy based on very limited evidence concluded that a thorough benefit-risk analysis is needed, followed by close monitoring when clozapine is continued during pregnancy [77]. The decision should consider the substantial risks to the mother and fetus/infant from untreated schizophrenia [78]. Clozapine use during breastfeeding is widely contraindicated because clozapine is excreted into breast milk [63, 76, 79,80,81].

4 Clozapine Treatment

4.1 Initiating Treatment

Major factors influencing blood clozapine concentrations include those significantly elevating clozapine blood levels, such as female sex (estrogen), older age, Asian/Amerindian ancestry, obesity, inflammation (from infection, rapid clozapine titration), high levels of caffeine use, coadministration of valproic acid, low CYP1A2 expression, and coadministration of CYP1A2 inhibitors; conversely, clozapine blood levels are lowered by smoking and other CYP1A2 inducers, including phenobarbital, phenytoin, and topiramate dosage > 400 mg/day (Table 1) [62, 82,83,84,85,86].

Caffeine and tobacco consumption are common and, although their effects on clozapine metabolism can be compensated through drug titration, as with the introduction or removal of concomitant medications, patients should be cautioned about changing their daily intake of these substances. Studies identifying a clinically relevant change in caffeine intake are lacking, but a relevant change may be > 1 cup of coffee or > 2 cans of caffeinated beverages per day in non-smoking patients (> 3 cups of coffee or > 6 cans of caffeinated beverages in smokers) [82].

Inflammation reduces CYP1A2 enzyme activity and increases clozapine blood levels; therefore, it is recommended to halve the clozapine dose in people with severe infection, including symptomatic COVID-19, until the patient has been 3 days without fever, after which the prior clozapine dose can be resumed [87].

The minimum trough level for clozapine in plasma associated with a good therapeutic response is generally thought to be 350 ng/mL, whilst levels above 600 ng/mL are associated with higher risk for dose-dependent side effects such as seizures [88, 89]; therefore, the lowest effective clozapine level should be targeted when therapeutic drug monitoring is used (see Sect. 4.6, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring). Some patients only respond to higher clozapine levels, and this may warrant higher dosages, combined with the use of prophylactic anticonvulsive therapy [62, 63].

When clozapine treatment is started in an in-patient setting, it is recommended to start at 12.5 mg once or twice a day on day one, followed by daily dosage incrementation by 25–50 mg up to a minimum therapeutic dosage (in adults generally 250–450 mg/day depending on sex, race, and smoking status), if tolerated. Older adults should start with 12.5 mg on the first day and daily dosage incrementation by 25 mg [63]. In the community or other settings where patients are not under continuous monitoring, slower titration should be used (see Beck et al. for a community titration schedule [90]).

Most patients with TRS will be switching from a failed antipsychotic therapy. The dosage of the failed antipsychotic should be tapered down during the initiation of treatment with clozapine. Our experience indicates that the best way to cross-taper is to keep the dose of the failed antipsychotic constant during the first week as clozapine titration is initiated, and then to gradually reduce the dose by about 25% per week, depending on the degree of symptomatic stability, the adverse effect burden during the overlap, and the ability to increase clozapine to a therapeutic dose [90]. However, the rate of reduction of the insufficiently effective antipsychotic may need to be adjusted depending on the rate of the clozapine up-titration, the side-effect profile of the failed antipsychotic and overlapping treatment, and how well the patient tolerates and responds to clozapine.

The rate of clozapine titration may influence the occurrence of some adverse events, including benign hyperthermia, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, and risk for myocarditis, pneumonia, agranulocytosis, and seizures [65, 82]. More gradual titration combined with careful monitoring may reduce the occurrence and severity of these events. A 2022 guideline proposes personalized titration schedules based on patient ancestry, sex, smoking status and other characteristics that influence clozapine metabolism [82]. These detailed schedules, which include weekly dosing targets and blood clozapine levels during titration are summarized in Table 2. During titration, excessive sedation, orthostatic hypotension, blood clozapine levels exceeding the limit for that week, and signs of inflammation (e.g., elevation in C-reactive protein) are reasons for pausing dosage escalation [82]. See Sect. 5 Side-Effect Monitoring and Management, and follow clozapine clinical monitoring recommendations.

4.2 Measuring Response to Therapy

Where possible, use a standardized symptom-rating scale, such as the 30-item Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) [91], or a standardized brief psychiatric rating scale, such as the six-item PANSS-6 [92,93,94,95] (Table 3) at baseline and subsequently to determine responses to therapy.

4.3 Monitoring for Side Effects During the Titration Phase

Clozapine is associated with side effects (e.g., constipation, dizziness, drowsiness, leukopenia, sialorrhea, tachycardia, and weight gain), as well as potentially life-threatening adverse events (e.g., agranulocytosis, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, neutropenia, agranulocytosis, paralytic ileus, pneumonia, and seizures) that warrant vigilant monitoring following established protocols, especially while titrating up to the therapeutic dose and during the first months of treatment (see Sect. 5) [31]. During this critical period, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) provides useful feedback for dosing and confirmation of adherence (see Sect. 4.6). Careful monitoring is also critical for detection and proactive management of side effects before they impact on treatment adherence [65].

4.4 Clozapine Trial Duration

After therapeutic plasma levels are achieved, Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Consensus Guidelines indicate that patients should receive clozapine with careful monitoring for at least 12 weeks, and ideally longer, before evaluating response, unless it cannot be tolerated [7]. In patients with strong negative symptoms, aggression, and/or those at high risk of suicide, a minimum trial duration of at least 16 weeks, and ideally longer, is recommended before evaluating response, unless it is not tolerated [96].

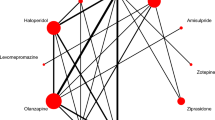

In patients with clozapine-resistant schizophrenia (CRS) [7], various pharmacologic augmentation strategies have been studied and can be tried [97,98,99]. In a naturalistic, nationwide database study, the only antipsychotic augmentation of clozapine that was superior to clozapine monotherapy for reducing the risk of hospitalization was the addition of the partial D2 agonist aripiprazole [100]. However, the most convincing evidence for efficacious augmentation of clozapine in CRS exists for electroconvulsive treatment [101].

4.5 Discontinuing Clozapine

A decision to discontinue clozapine may be based on issues with efficacy, adherence, or tolerability, or on the emergence of life-threatening adverse effects (see Sect. 5). When the decision is not based on an emergency, the clozapine dosage should ideally be tapered over 6 months if possible, with cross-titration to an alternative antipsychotic chosen based on history of response, tolerability, and side-effect profile (Fig. 3) [102]. Regardless of the reason for discontinuation, patients should be monitored closely for the onset or worsening of psychosis, and absolute neutrophil count monitoring should continue for 2 weeks after discontinuation.

adapted from reference [102], permission not required)

Provisional protocol for discontinuation of clozapine (

4.6 Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

TDM is not needed if the patient is tolerating and responding to clozapine. However, it can be useful during initial titration of clozapine and during maintenance when there are signs of relapse, onset of side effects that are known to be dose dependent, or changes in factors known to influence blood levels, such as concomitant medications or cigarette use [103, 104]. Poor adherence to therapy is a frequent cause of non-response that can be detected with TDM; however, low plasma levels may also be due to pharmacokinetic effects. Typical indications for TDM are listed in Table 4 [103].

The clozapine dose required to achieve and maintain blood levels in the therapeutic range varies greatly among patients. There may be high intra-individual variation in plasma levels even in stable patients [105], and some patients only respond after achieving blood clozapine levels above the reference range (350–600 ng/mL) [106].

TDM may be a useful tool for supporting dosing decisions because it provides direct feedback on blood concentrations without waiting for symptoms to respond or for side effects to develop [4]. This information can be used to optimize clozapine dosage (Table 5) [104]. Moreover, TDM may potentially increase prescriber confidence [107]. Lower doses/dose reductions may be necessary in patients with clinically significant renal or hepatic impairment (Fig. 4).

The typical evolution of clozapine-induced myocarditis. bpm beats per minute, CRP C-reactive protein, HR heart rate, LV left ventricular, ULN upper limit of normal [131] (reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications)

5 Side Effect Monitoring and Management

Clozapine is associated with side effects of varying severity, including FDA “black box” warnings for severe neutropenia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, and syncope, seizure, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and mitral valve incompetence, as well as increased mortality in older adults with dementia-related psychosis (see prescribing information for complete list) [62]. Risk-benefit considerations should be weighed against the fact that clozapine is the only approved treatment for TRS and that clozapine treatment significantly lowers all-cause mortality [34,35,36].

Adverse effects should be monitored regularly according to local guidelines, which may vary between jurisdictions. Several countries require enrolment in clozapine patient-monitoring registries. Other side effects like nocturnal enuresis or incontinence can be troubling to the patient, and have major consequences if their burden leads to nonadherence and psychotic relapse [108].

Patient-compiled side-effect rating scales can provide a starting point for discussing the topic with patients. A systematic review of rating scales for side effects associated with antipsychotic medications suggested that the Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser Side Effects Rating Scale for Patients (UKU-SERS-Pat), Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effect Rating Scale (LUNSERS), and the Glasgow Antipsychotic Side-effects Scale (GASS) are useful for this purpose [109]. A validated, clozapine-specific version of the GASS (GASS-C) has been developed [110]. However, several potentially life-threatening side effects are not detected by patient-compiled rating scales. An audit conducted in UK mental health services found that patient-compiled rating scales may be underutilized [111].

5.1 Agranulocytosis: Laboratory Tests, Clinical Complications

Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis (severe neutropenia) is a potentially life-threatening decrease in absolute neutrophil count to levels below 500/mm3 and increases susceptibility to infections [112]. It occurs most frequently during the first month of treatment and affects approximately 1% of treated patients [113, 114]. These reactions are unpredictable and do not appear to be dose dependent [115]. Findings from genomic studies suggest the involvement of multiple genes, including the solute carrier organic anion transporter 1B3/1B7 and members of the human leukocyte antigen complex [116]. People of African, Middle Eastern, or West Indian descent may present with benign ethnic neutropenia (BEN; absolute neutrophil counts 1000–1800/mm3) [117]. BEN is not associated with frequent or severe infections, or a higher risk of agranulocytosis with clozapine treatment [118]; however, the lower baseline neutrophil levels require a separate monitoring scheme [62].

5.1.1 Agranulocytosis: Detection and Clinical Complications

Blood cell counts have been successful for preventing fatalities and are required in all treated patients. The FDA requires weekly monitoring during the first 6 months of treatment; if absolute neutrophil count remains ≥ 1500/µL (≥ 1000/µL for BEN), then monitoring may be reduced to every 2 weeks for the next 6 months, and monthly thereafter (Tables 6 and 7) [62].

The EMA requires weekly monitoring of absolute neutrophil count for the first 18 weeks of treatment, followed by monthly for the duration of treatment [63].

Rechallenge after recovery from clozapine-induced neutropenia is envisioned in guidance from the FDA. A summary of 259 cases of clozapine rechallenge after major adverse events reported a success rate of 63.0% (128/203) for patients with neutropenia, and 17.7% (3/17) for those with agranulocytosis [119]. According to the reviewed cases, rechallenge may be more successful with slow titration and coadministration of low-dose lithium (300–600 mg/day), which stimulates the bone marrow production of leucocytes. Although lithium stimulates leucocyte production, it may also mask the onset of agranulocytosis. Preliminary data suggest that granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, widely used to reduce the incidence and severity of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, may be useful for stimulating leukopoiesis during clozapine rechallenge [120,121,122,123].

5.2 Myocarditis and Other Cardiological Adverse Events

Clozapine is associated with the risk of rare myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Myocarditis is an acute condition involving inflammation of the myocardium that usually occurs during the first month of treatment [124, 125], while cardiomyopathy involves structural changes to the left ventricle that occur over months to years [126]. These conditions do not appear to be dose dependent. In a meta-analysis of cardiac adverse drug reactions among 258,961 people exposed to clozapine, the myocarditis rate was 0.7% (95% CI 0.3–1.6) and the rate of cardiomyopathy was 0.6% (95% CI 0.2–2.3) [127]. The meta-analysis included mainly retrospective studies that used a variety of definitions and markers. Subsequent reports of presumptive myocarditis based on sensitive laboratory tests [128] or retrospectively identified myocarditis (cases defined as flu-like symptoms plus ≥ 1 symptom/sign of cardiac dysfunction plus ≥ 1 indicative diagnostic abnormality and no evidence of a viral cause) [129], suggest that the incidence may be higher. The risk of myocarditis is higher among patients commencing clozapine treatment while receiving valproate [130]. In a review of case reports, the success rate of clozapine rechallenge after clozapine-associated myocarditis was 64.7% (11/17) [119].

5.2.1 Presentation of Early Cardiological Adverse Events

Although rare, cardiological adverse events are potentially life-threatening and their onset can be difficult to diagnose. They may occur more frequently in the first weeks after treatment initiation [124]; however, they are not strictly related to clozapine titration or dosage dependent, therefore vigilance and a proactive attitude are imperative over the entire course of clozapine treatment (Fig. 5) [131].

Monitoring for clozapine-induced cardiotoxicity [90, 131,132,133]. Less or more frequent monitoring may be appropriate depending on the clinical situation and local guidelines. aSymptoms may include chest pain, edema, shortness of breath, and other signs associated with heart failure. If signs or symptoms develop, or cardio markers are elevated, increase the frequency of troponin and C-reactive protein tests until normalized

Signs and symptoms of myocarditis may include fever, malaise, tachycardia/palpitations, arrhythmias, chest pain, and/or symptoms associated with heart failure like dyspnea, tachypnea, and fatigue [63]; however, the clinical presentation is variable and many of the symptoms are not specific to myocarditis [124], highlighting the need for monitoring markers of cardiotoxicity and cardiovascular risk factors (Fig. 5) [90, 131,132,133]. Troponin I is a sensitive and specific marker for myocardial damage. Echocardiography may be indicated when clinical signs or abnormal biomarkers are present.

Cardiomyopathy often presents with decreased exercise tolerance, peripheral edema, and myocardial congestion, and can lead to the development of malignant arrhythmias, cardiac insufficiency, and pump failure [132]. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP are sensitive and specific markers for heart failure and cardiomyopathy.

In most cases clozapine will be discontinued once myocarditis or cardiomyopathy develops, but there may be circumstances where the benefits outweigh the risks. Any decision to rechallenge should be made with the consultation of a cardiologist or heart failure specialist, with the rechallenge attempted at least 6 months after the episode of clozapine-associated myocarditis using a titration in which dosage is increased slowly (e.g., by 25 mg per week) [133].

5.3 Gastrointestinal Hypomotility

Clozapine use can cause gastrointestinal hypomotility in any part of the digestive tract and, depending on the location, this can lead to constipation with increased risk of paralytic ileus and pseudo-obstruction, gastroparesis, or dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia and death [134]. A meta-analysis of 32 studies (n = 2,013 patients) showed that the pooled prevalence of constipation associated with clozapine was 31.2% [135]. A comprehensive review of publications up to 2010 revealed a mortality rate for life-threatening gastrointestinal hypomotility of 15.0–27.5% [136], while mortality in patients who develop paralytic ileus was 43.7% [137]. The risk is highest during the first 4 months of treatment, but remains throughout treatment [138]. The risk increases with age and clozapine dose, and is higher in patients receiving concomitant treatment with anticholinergic medications, other medications with anticholinergic properties, or opioids [139].

5.3.1 Symptoms and Signs

Symptoms may include abdominal pain or distention, infrequent/difficult defecation, and other well-known symptoms of constipation; however, patients with schizophrenia may not be aware of abdominal symptoms, and detection should not rely on spontaneous reporting. Simply asking the patient whether they are experiencing constipation may not be reliable. Evaluation can use a brief constipation scale such as the eight-item Constipation Assessment Scale (Table 8) [140], or the ROME IV instrument [141].

Comparing the results from patient-reported constipation with objective data from gastrointestinal motility testing revealed that self-reporting greatly underestimates the presence of this frequent and potentially life-threatening side effect, highlighting the importance of educating the patient and family on the need for vigilance [142, 143].

5.3.2 Protocols and Procedures to Prevent Gastrointestinal Hypomotility

The best strategy for preventing serious gastrointestinal outcomes is to inform and remind the patient of the potential risks, and counsel them on the importance of a healthy diet, adequate fluid intake, and physical activity. Concomitant medications should be monitored to avoid drugs known to promote constipation or reduce gastrointestinal motility (e.g., opioids, antihistamines, other anticholinergic drugs). This approach should be combined with frequent constipation screening (e.g., weekly administration of a brief scale during the first few months). Abdominal auscultation, palpation, and percussion may be useful for identifying blockage.

Proactive measures might include the co-prescription of prophylactic laxatives in patients with risk factors (e.g., advanced age, history of constipation). A targeted approach in which laxatives are administered only when needed may avoid unnecessary treatment but requires timely diagnosis of constipation to prevent serious/fatal adverse events. Together, the prevalence and severity of potential adverse outcomes, insensitivity of self-reported screening, and impracticality of screening with gastrointestinal motility test argue for the use of prophylactic laxatives. There are potential side effects with long-term laxative use, and these need to be weighed against the benefits. The FDA recommends “considering prophylactic laxatives in high-risk patients” [62].

5.3.3 Treatment

Management includes clozapine dose reduction, osmotic laxative, stimulant laxative, or docusate stool softeners. Patients not responding to these should be referred to gastroenterology. When a bowel obstruction is suspected, stimulants and bulk-forming laxatives should not be used, and the patient should be referred for urgent surgical review.

5.4 Clozapine-Associated Pneumonia

The risk of pneumonia is higher with clozapine than with other second-generation antipsychotics [144,145,146], and pneumonia associated with clozapine has a higher mortality rate than its better-recognized cardiovascular and hematological adverse effects [145, 147]. Several clozapine-associated effects may contribute to increasing the risk of aspiration and the onset of pneumonia, including sialorrhea, sedation, and dysphagia/decreased gastrointestinal motility; moreover, clozapine blood levels may increase once an infection is established, and this may be compounded in smokers who are forced to stop smoking because of pneumonia. A finding of pneumonia may require a reduction or interruption of clozapine therapy until the infection is resolved [147]. This highlights the importance of reducing the chances of side effects by using the lowest effective clozapine dosage, while remaining vigilant for signs of respiratory tract infection. Update and maintain vaccination against seasonal influenza and COVID-19. Family members and caregivers should be informed of the dangers, risk factors, and signs of aspiration pneumonia.

5.5 Sialorrhea

Sialorrhea is one the most frequent adverse events of clozapine therapy (prevalence up to 90%), and may reduce treatment tolerance and adherence [148, 149]. Clozapine-induced sialorrhea may increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia in fragile patients and should be monitored at every visit. It is addressed in brief side-effect scales (e.g., the GASS-C) and can be further monitored using, for example, the two-item Drooling Severity and Frequency Scale (DSFS) [150], or the five-point Nocturnal Hypersalivation Rating Scale (NHRS) [151].

Treatment may include clozapine dose reduction, when possible, and anticholinergics. A meta-analysis of 19 studies suggests that diphenhydramine, propantheline, chlorpheniramine, and benzamide derivatives can reduce the rates of clozapine-induced sialorrhea, although caution is warranted because some agents (e.g., propantheline) increase the risk of constipation [152]. Thus, locally applied anticholinergic preparations with limited systemic exposure should be used [153, 154], but care should be taken to prevent accidental or intentional ingestion of toxic quantities, and they should be avoided in patients who struggle to follow administration instructions. In severe cases, when other approaches have failed, injection of botulinum toxin B into the salivary glands can be considered [155].

5.6 Clozapine-Induced Convulsions

Clozapine may cause EEG changes, but any association between EEG changes and the onset of seizures is unclear and generally prophylactic anticonvulsant therapy is not indicated in the absence of a history of or risk factors for seizures [156]. Clozapine lowers the seizure threshold in a dose-dependent fashion [157], and is associated with seizures at an annual incidence of approximately 5% [158, 159]. Whilst seizures have been reported in patients receiving low doses, the risk is increased at higher doses [160], and the FDA label urges caution when prescribing clozapine in patients with a history of seizures or other predisposing risk factors for seizure (e.g., CNS pathology, medications that lower the seizure threshold, alcohol abuse) [62].

Management of clozapine-induced seizures requires measuring serum drug concentrations and reducing the dose, as well as introducing an anticonvulsant. Consider adding valproate (not in women of child-bearing potential) or lamotrigine as seizure prophylaxis at higher clozapine doses [159]. Dose reduction and/or addition of antiepileptic therapy allows most patients to continue clozapine therapy [161].

5.7 Metabolic Syndrome and Clozapine

Cardiovascular mortality contributes significantly to the reduced life expectancy of people with schizophrenia [162, 163]. Metabolic changes include hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and weight gain [62, 164], which predispose patients to diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Clozapine is the antipsychotic with the highest risk of weight gain and other metabolic effects [164]. Clozapine-associated changes in glucose, insulin, and weight begin within 6–10 weeks of starting treatment [164, 165].

Clozapine’s action at numerous receptors has been implicated in these effects [166, 167], and the presence of one component of the metabolic syndrome is a risk factor for the other components [168].

FDA recommendations include regular monitoring of glucose levels, body weight, and symptoms of hyperglycemia (e.g., polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, weakness). Hemoglobin A1C levels are more sensitive than fasting glucose levels to detect prediabetes and diabetes, and do not require fasting status [169].

Options for management include considering metformin treatment to improve hyperglycemia, elevated triglycerides, and obesity [170, 171]. Glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists can increase insulin secretion while decreasing glucagon secretion and food intake, and have a larger effect on weight loss than metformin [172]. Lifestyle changes should clearly be promoted [173].

6 Conclusion

Patients meeting the criterial for TRS should be treated as soon as possible to improve their chances of achieving remission with clozapine; however, concern over side effects, monitoring requirements, and inexperience with prescribing often result in long delays that can expose patients to unnecessary risks and compromise their chances of achieving favorable long-term outcomes [4]. We have provided an overview of strategies to support early initiation of clozapine based on the latest evidence and our clinical experience, and have summarized the key elements in a checklist. A practical, evidence-based checklist for identifying and managing patients with TRS, such as provided here, should increase confidence in prescribing and monitoring clozapine, reducing treatment delays, and improving outcomes.

Change history

17 August 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-022-00946-w

References

Kahn RS, Sommer IE, Murray RM, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR, Cannon TD, et al. Schizophrenia. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2015;1:15067. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.67.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3.

McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev US. 2008;30:67–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxn001.

Kane JM, Agid O, Baldwin ML, Howes O, Lindenmayer J-P, Marder S, et al. Clinical guidance on the identification and management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18com12123.

Buckley PF. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2020;18:364–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20200025.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults: Treatment and Management: Updated Edition 2014 [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2014 [cited 2022 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK248060/

Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, de Bartolomeis A, van Beveren NJM, Birnbaum ML, et al. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Treatment response and resistance in psychosis (TRRIP) working group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:216–29. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050503.

Lally J, Ajnakina O, Di Forti M, Trotta A, Demjaha A, Kolliakou A, et al. Two distinct patterns of treatment resistance: clinical predictors of treatment resistance in first-episode schizophrenia spectrum psychoses. Psychol Med. 2016;46:3231–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002014.

Correll CU, Brevig T, Brain C. Exploration of treatment-resistant schizophrenia subtypes based on a survey of 204 US psychiatrists. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:3461–73. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S234813.

Siskind D, Orr S, Sinha S, Yu O, Brijball B, Warren N, et al. Rates of treatment-resistant schizophrenia from first-episode cohorts: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2022;220:115–20. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.61.

Mouchlianitis E, McCutcheon R, Howes OD. Brain-imaging studies of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:451–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00540-4.

Potkin SG, Kane JM, Correll CU, Lindenmayer J-P, Agid O, Marder SR, et al. The neurobiology of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: paths to antipsychotic resistance and a roadmap for future research. NPJ Schizophr. 2020;6:1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-019-0090-z.

Howes OD, Kapur S. A neurobiological hypothesis for the classification of schizophrenia: type A (hyperdopaminergic) and type B (normodopaminergic). Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2014;205:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.138578.

Brugger SP, Angelescu I, Abi-Dargham A, Mizrahi R, Shahrezaei V, Howes OD. Heterogeneity of striatal dopamine function in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of variance. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:215–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.07.008.

Demjaha A, Murray RM, McGuire PK, Kapur S, Howes OD. Dopamine synthesis capacity in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1203–10. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010144.

Jauhar S, McCutcheon R, Borgan F, Veronese M, Nour M, Pepper F, et al. The relationship between cortical glutamate and striatal dopamine in first-episode psychosis: a cross-sectional multimodal PET and magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:816–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30268-2.

Veronese M, Santangelo B, Jauhar S, D’Ambrosio E, Demjaha A, Salimbeni H, et al. A potential biomarker for treatment stratification in psychosis: evaluation of an [18F] FDOPA PET imaging approach. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:1122–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-00866-7.

Demjaha A, Egerton A, Murray RM, Kapur S, Howes OD, Stone JM, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in schizophrenia associated with elevated glutamate levels but normal dopamine function. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:e11-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.06.011.

Pillinger T, Rogdaki M, McCutcheon RA, Hathway P, Egerton A, Howes OD. Altered glutamatergic response and functional connectivity in treatment resistant schizophrenia: the effect of riluzole and therapeutic implications. Psychopharmacology. 2019;236:1985–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-019-5188-5.

Mouchlianitis E, Bloomfield MAP, Law V, Beck K, Selvaraj S, Rasquinha N, et al. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients show elevated anterior cingulate cortex glutamate compared to treatment-responsive. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:744–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv151.

Jauhar S, Veronese M, Nour MM, Rogdaki M, Hathway P, Turkheimer FE, et al. Determinants of treatment response in first-episode psychosis: an 18F-DOPA PET study. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:1502–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0042-4.

Elkis H, Buckley PF. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39:239–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2016.01.006.

Wimberley T, Støvring H, Sørensen HJ, Horsdal HT, MacCabe JH, Gasse C. Predictors of treatment resistance in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:358–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00575-1.

Stokes I, Griffiths SL, Jones R, Everard L, Jones PB, Fowler D, et al. Prevalence of treatment resistance and clozapine use in early intervention services. BJPsych Open. 2020;6: e107. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.89.

Beck K, McCutcheon R, Stephenson L, Schilderman M, Patel N, Ramsay R, et al. Prevalence of treatment-resistant psychoses in the community: a naturalistic study. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:1248–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881119855995.

Kennedy JL, Altar CA, Taylor DL, Degtiar I, Hornberger JC. The social and economic burden of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:63–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e32836508e6.

Correll CU, Brevig T, Brain C. Patient characteristics, burden and pharmacotherapy of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: results from a survey of 204 US psychiatrists. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2318-x.

Iasevoli F, Giordano S, Balletta R, Latte G, Formato MV, Prinzivalli E, et al. Treatment resistant schizophrenia is associated with the worst community functioning among severely-ill highly-disabling psychiatric conditions and is the most relevant predictor of poorer achievements in functional milestones. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;65:34–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.08.010.

Velligan DI, Brain C, Bouérat Duvold L, Agid O. Caregiver burdens associated with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a quantitative caregiver survey of experiences, attitudes, and perceptions. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00584.

Kaar SJ, Natesan S, McCutcheon R, Howes OD. Antipsychotics: mechanisms underlying clinical response and side-effects and novel treatment approaches based on pathophysiology. Neuropharmacology. 2020;172: 107704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107704.

Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, Falkai P, Honer WG, Röh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders-a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:487. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01613-2.

McQueen G, Sendt K-V, Gillespie A, Avila A, Lally J, Vallianatou K, et al. Changes in brain glutamate on switching to clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47:662–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa156.

Mizuno Y, McCutcheon RA, Brugger SP, Howes OD. Heterogeneity and efficacy of antipsychotic treatment for schizophrenia with or without treatment resistance: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;45:622–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0577-3.

Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, Haddad PM, Patel MX, Korhonen P. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:603–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081224.

Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374:620–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X.

Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Mehtälä J, Vattulainen P, Correll CU, Tiihonen J. 20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry. 2020;19:61–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20699.

Vermeulen JM, van Rooijen G, van de Kerkhof MPJ, Sutterland AL, Correll CU, de Haan L. Clozapine and long-term mortality risk in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies lasting 1.1–12.5 years. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:315–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby052.

Meltzer HY, Alphs L, Green AI, Altamura AC, Anand R, Bertoldi A, et al. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: international suicide prevention trial (InterSePT). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:82–91. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.82.

Vanasse A, Blais L, Courteau J, Cohen AA, Roberge P, Larouche A, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia treatment: a real-world observational study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134:374–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12621.

Wimberley T, MacCabe JH, Laursen TM, Sørensen HJ, Astrup A, Horsdal HT, et al. Mortality and self-harm in association with clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:990–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16091097.

Cho J, Hayes RD, Jewell A, Kadra G, Shetty H, MacCabe JH, et al. Clozapine and all-cause mortality in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a historical cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139:237–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12989.

Masuda T, Misawa F, Takase M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Association with hospitalization and all-cause discontinuation among patients with schizophrenia on clozapine vs other oral second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76:1052–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1702.

Shimomura Y, Kikuchi Y, Suzuki T, Uchida H, Mimura M, Takeuchi H. Antipsychotic treatment strategies for acute phase and treatment resistance in schizophrenia: a systematic review of the guidelines and algorithms. Schizophr Res. 2021;236:142–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2021.07.040.

Bachmann CJ, Aagaard L, Bernardo M, Brandt L, Cartabia M, Clavenna A, et al. International trends in clozapine use: a study in 17 countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136:37–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12742.

Howes OD, Vergunst F, Gee S, McGuire P, Kapur S, Taylor D. Adherence to treatment guidelines in clinical practice: study of antipsychotic treatment prior to clozapine initiation. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:481–5. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.105833.

Thien K, O’Donoghue B. Delays and barriers to the commencement of clozapine in eligible people with a psychotic disorder: a literature review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13:18–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12683.

Taylor DM, Young C, Paton C. Prior antipsychotic prescribing in patients currently receiving clozapine: a case note review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:30–4. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v64n0107.

Nielsen J, Dahm M, Lublin H, Taylor D. Psychiatrists’ attitude towards and knowledge of clozapine treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:965–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881108100320.

Farooq S, Choudry A, Cohen D, Naeem F, Ayub M. Barriers to using clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: systematic review. BJPsych Bull. 2019;43:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2018.67.

Singh B, Hughes AJ, Roerig JL. Comfort level and barriers to the appropriate use of clozapine: a preliminary survey of US psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44:53–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-019-01134-7.

Verdoux H, Quiles C, Bachmann CJ, Siskind D. Prescriber and institutional barriers and facilitators of clozapine use: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:10–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.046.

Gören JL, Rose AJ, Smith EG, Ney JP. The business case for expanded clozapine utilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:1197–205. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500507.

Nielsen J, Nielsen RE, Correll CU. Predictors of clozapine response in patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia: results from a Danish Register Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:678–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e318267b3cd.

Üçok A, Çikrikçili U, Karabulut S, Salaj A, Öztürk M, Tabak Ö, et al. Delayed initiation of clozapine may be related to poor response in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30:290–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0000000000000086.

Yada Y, Yoshimura B, Kishi Y. Correlation between delay in initiating clozapine and symptomatic improvement. Schizophr Res. 2015;168:585–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.045.

Yoshimura B, Yada Y, So R, Takaki M, Yamada N. The critical treatment window of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: secondary analysis of an observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;250:65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.064.

Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, Patel MX, MacCabe JH, Howes OD, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47:1981–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000435.

Ortiz BB, Higuchi CH, Noto C, Joyce DW, Correll CU, Bressan RA, et al. A symptom combination predicting treatment-resistant schizophrenia—a strategy for real-world clinical practice. Schizophr Res. 2020;218:195–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.01.002.

Chan SKW, Chan HYV, Honer WG, Bastiampillai T, Suen YN, Yeung WS, et al. Predictors of treatment-resistant and clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: a 12-year follow-up study of first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47:485–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa145.

Dempster K, Li A, Sabesan P, Norman R, Palaniyappan L. Treatment resistance: a time-based approach for early identification in first episode psychosis. J Pers Med. 2021;11:711. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080711.

De Berardis D, Rapini G, Olivieri L, Di Nicola D, Tomasetti C, Valchera A, et al. Safety of antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia: a focus on the adverse effects of clozapine. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:237–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098618756261.

US Food and Drug Administration. Clozaril (clozapine) Prescribing information [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/019758s088lbl.pdf

European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA). SmPC Leponex (clozapine) [Internet]. 2002. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/summary-information-referral-opinion-following-arbitration-pursuant-article-30-council-directive/83/ec-leponex-associated-names-international-non-proprietary-name-inn-clozapine-background-inform_en.pdf

Nielsen J, Young C, Ifteni P, Kishimoto T, Xiang Y-T, Schulte PFJ, et al. Worldwide differences in regulations of clozapine use. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:149–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-016-0311-1.

Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, Kane JM. Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:603–13. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r08064.

Australia - National Prescribing Service MedicineWise. Clozaril [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.nps.org.au/medicine-finder/clozaril-tablets#full-pi

Canada - AA PHARMA. CLOZAPINE PRODUCT MONOGRAPH [Internet]. Available from: https://www.aapharma.ca/downloads/en/PIL/2020/Clozapine-PrMono-ENG-May_6_2020.pdf

Japan Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Clozapine [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000241004.pdf

Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, et al. World federation of societies of biological psychiatry (wfsbp) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:318–78. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2012.696143.

Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp116.

Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:48–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp115.

Abidi S, Mian I, Garcia-Ortega I, Lecomte T, Raedler T, Jackson K, et al. Canadian guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders in children and youth. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:635–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717720197.

Schneider C, Corrigall R, Hayes D, Kyriakopoulos M, Frangou S. Systematic review of the efficacy and tolerability of clozapine in the treatment of youth with early onset schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.08.001.

Krause M, Zhu Y, Huhn M, Schneider-Thoma J, Bighelli I, Chaimani A, et al. Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with schizophrenia: A network meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:659–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.03.008.

Renzenbrink M, Wand APF. A systematic review of clozapine’s effectiveness for primary psychotic and bipolar disorders in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2021;2:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220004172.

Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthøj B, Gattaz WF, et al. World federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia. Part 3: Update 2015 Management of special circumstances: depression, suicidality, substance use disorders and pregnancy and lactation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16:142–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2015.1009163.

Thanigaivel R, Bretag-Norris R, Amos A, McDermott B. A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes after clozapine continuation in pregnancy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2021.1936070.

Romaine E, McAllister-Williams RH. Guidelines on prescribing psychotropic medication during the perinatal period. Br J Hosp Med. 2019;80:27–32. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2019.80.1.27.

Fortinguerra F, Clavenna A, Bonati M. Psychotropic drug use during breastfeeding: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e547-556. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0326.

McAllister-Williams RH, Baldwin DS, Cantwell R, Easter A, Gilvarry E, Glover V, et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:519–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117699361.

Payne JL. Psychopharmacology in pregnancy and breastfeeding. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103:629–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2019.02.009.

de Leon J, Schoretsanitis G, Smith RL, Molden E, Solismaa A, Seppälä N, et al. An international adult guideline for making clozapine titration safer by using six ancestry-based personalized dosing titrations, CRP, and clozapine levels. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1625-6388.

González-Esquivel DF, Jung-Cook H, Baptista T, de Leon J. Amerindians may need clozapine dosing similar to that of Asians. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2021;14:177–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsmen.2020.11.003.

Ruan C-J, Zang Y-N, Wang C-Y, Cheng Y-H, Sun C, Spina E, et al. Clozapine metabolism in east asians and caucasians: a pilot exploration of the prevalence of poor metabolizers and a systematic review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39:135–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001018.

Clark SR, Warren NS, Kim G, Jankowiak D, Schubert KO, Kisely S, et al. Elevated clozapine levels associated with infection: A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2018;192:50–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.045.

Albitar O, Harun SN, Zainal H, Ibrahim B, Sheikh Ghadzi SM. Population pharmacokinetics of clozapine: a systematic review. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020:9872936. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9872936.

Siskind D, Honer WG, Clark S, Correll CU, Hasan A, Howes O, et al. Consensus statement on the use of clozapine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatry Neurosci JPN. 2020;45:222–3. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.200061.

Remington G, Agid O, Foussias G, Ferguson L, McDonald K, Powell V. Clozapine and therapeutic drug monitoring: is there sufficient evidence for an upper threshold? Psychopharmacology. 2013;225:505–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-012-2922-7.

Siskind D, Sharma M, Pawar M, Pearson E, Wagner E, Warren N, et al. Clozapine levels as a predictor for therapeutic response: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144:422–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13361.

Beck K, McCutcheon R, Bloomfield MAP, Gaughran F, Reis Marques T, MacCabe J, et al. The practical management of refractory schizophrenia–the Maudsley Treatment REview and Assessment Team service approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:427–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12327.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/13.2.261.

Østergaard SD, Lemming OM, Mors O, Correll CU, Bech P. PANSS-6: a brief rating scale for the measurement of severity in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133:436–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12526.

Østergaard SD, Opler MGA, Correll CU. Bridging the measurement gap between research and clinical care in schizophrenia: positive and negative syndrome scale-6 (PANSS-6) and other assessments based on the simplified negative and positive symptoms interview (SNAPSI). Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14:68–72.

Østergaard SD, Foldager L, Mors O, Bech P, Correll CU. The validity and sensitivity of PANSS-6 in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138:420–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12952.

Kølbæk P, Dines D, Holm T, Blicher AB, Sørensen RD, O’Leary KM, et al. Clinical validation of ratings on the six-item positive and negative syndrome scale obtained via the simplified negative and positive symptoms interview. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35:1081–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881121996890.

Wagner E, Kane JM, Correll CU, Howes O, Siskind D, Honer WG, et al. Clozapine combination and augmentation strategies in patients with schizophrenia-recommendations from an international expert survey among the treatment response and resistance in psychosis (TRRIP) working group. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:1459–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa060.

Wagner E, Löhrs L, Siskind D, Honer WG, Falkai P, Hasan A. Clozapine augmentation strategies—a systematic meta-review of available evidence. Treatment options for clozapine resistance. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:423–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881118822171.

Siskind DJ, Lee M, Ravindran A, Zhang Q, Ma E, Motamarri B, et al. Augmentation strategies for clozapine refractory schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52:751–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418772351.

Correll CU, Rubio JM, Inczedy-Farkas G, Birnbaum ML, Kane JM, Leucht S. Efficacy of 42 pharmacologic cotreatment strategies added to antipsychotic monotherapy in schizophrenia: systematic overview and quality appraisal of the meta-analytic evidence. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74:675–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0624.

Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Mehtälä J, Vattulainen P, Correll CU, Tanskanen A. Association of antipsychotic polypharmacy vs monotherapy with psychiatric rehospitalization among adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76:499–507. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4320.

Wang G, Zheng W, Li X-B, Wang S-B, Cai D-B, Yang X-H, et al. ECT augmentation of clozapine for clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;105:23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.002.

Blackman G, Oloyede E, Horowitz M, Harland R, Taylor D, MacCabe J, et al. Reducing the risk of withdrawal symptoms and relapse following clozapine discontinuation-is it feasible to develop evidence-based guidelines? Schizophr Bull. 2022;48:176–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbab103.

Hiemke C, Bergemann N, Clement HW, Conca A, Deckert J, Domschke K, et al. Consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology: update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51:9–62. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-116492.

Schoretsanitis G, Kane JM, Correll CU, Marder SR, Citrome L, Newcomer JW, et al. Blood levels to optimize antipsychotic treatment in clinical practice: a joint consensus statement of the American society of clinical psychopharmacology and the therapeutic drug monitoring task force of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81:19. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.19cs13169.

Turrion MC, Perez J, Bernardo M, Fernandez-Egea E. Intra-individual variation of clozapine and norclozapine plasma levels in clinical practice. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2020;13:31–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2019.03.002.

Stark A, Scott J. A review of the use of clozapine levels to guide treatment and determine cause of death. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46:816–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412438871.

Kitchen D, Till A, Xavier P. Routine clozapine assay monitoring to improve the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. BJPsych Bull. 2021;2:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2021.36.

Tanzer T, Warren N, McMahon L, Barras M, Kisely S, Brooks E, et al. Treatment strategies for clozapine-induced nocturnal enuresis and urinary incontinence: a systematic review. CNS Spectr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852922000050.

van Strien AM, Keijsers CJPW, Derijks HJ, van Marum RJ. Rating scales to measure side effects of antipsychotic medication: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:857–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881115593893.

Hynes C, Keating D, McWilliams S, Madigan K, Kinsella A, Maidment I, et al. Glasgow antipsychotic side-effects scale for clozapine—development and validation of a clozapine-specific side-effects scale. Schizophr Res. 2015;168:505–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.052.

Barnes TRE, MacCabe JH, Kane JM, Delgado O, Paton C. The physical health and side-effect monitoring of patients prescribed clozapine: data from a clinical audit conducted in UK mental health services. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320937908. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125320937908.

Mijovic A, MacCabe JH. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Ann Hematol. 2020;99:2477–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-020-04215-y.

Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Schwimmer JL, Schaaf JA. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:162–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199307153290303.

Myles N, Myles H, Xia S, Large M, Kisely S, Galletly C, et al. Meta-analysis examining the epidemiology of clozapine-associated neutropenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138:101–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12898.

Flanagan RJ, Dunk L. Haematological toxicity of drugs used in psychiatry. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(Suppl 1):27–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.917.

Legge SE, Walters JT. Genetics of clozapine-associated neutropenia: recent advances, challenges and future perspective. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20:279–90. https://doi.org/10.2217/pgs-2018-0188.

Oloyede E, Dzahini O, Barnes N, Mijovic A, Gandhi S, Stuart-Smith S, et al. Benign ethnic neutropenia: an analysis of prevalence, timing and identification accuracy in two large inner-city NHS hospitals. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:502. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03514-6.

Manu P, Sarvaiya N, Rogozea LM, Kane JM, Correll CU. Benign ethnic neutropenia and clozapine use: a systematic review of the evidence and treatment recommendations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:e909-916. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15r10085.

Manu P, Lapitskaya Y, Shaikh A, Nielsen J. Clozapine rechallenge after major adverse effects: clinical guidelines based on 259 cases. Am J Ther. 2018;25:e218–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0000000000000715.

Lally J, Malik S, Krivoy A, Whiskey E, Taylor DM, Gaughran FP, et al. The use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in clozapine rechallenge: a systematic review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37:600–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000767.

Myles N, Myles H, Clark SR, Bird R, Siskind D. Use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to prevent recurrent clozapine-induced neutropenia on drug rechallenge: a systematic review of the literature and clinical recommendations. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51:980–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417720516.

Silva E, Higgins M, Hammer B, Stephenson P. Clozapine rechallenge and initiation despite neutropenia—a practical, step-by-step guide. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:279. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02592-2.

Béchard L, Corbeil O, Plante M, Thivierge M-A, Lafrenière C-É, Roy M-A, et al. Clozapine rechallenge following neutropenia using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: a Quebec case series. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35:1152–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811211029737.

Bellissima BL, Tingle MD, Cicović A, Alawami M, Kenedi C. A systematic review of clozapine-induced myocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2018;259:122–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.102.

De Las CC, Sanz EJ, Ruan C-J, de Leon J. Clozapine-associated myocarditis in the World Health Organization’s pharmacovigilance database: Focus on reports from various countries. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2021;S1888–9891(21):00070–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2021.07.004.

Alawami M, Wasywich C, Cicovic A, Kenedi C. A systematic review of clozapine induced cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:315–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.103.

Siskind D, Sidhu A, Cross J, Chua Y-T, Myles N, Cohen D, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of rates of clozapine-associated myocarditis and cardiomyopathy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020;54:467–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867419898760.

Sandarsh S, Bishnoi RJ, Shashank RB, Miller BJ, Freudenreich O, McEvoy JP. Monitoring for myocarditis during treatment initiation with clozapine. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144:194–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13328.

Bellissima BL, Vara A, Helsby N, Garavan F, Tingle MD. Incidence and investigation of potential risk-factors for clozapine-associated myocarditis and cardiomyopathy in a New Zealand cohort. Psychiatry Res. 2021;299: 113873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113873.

Vickers M, Ramineni V, Malacova E, Eriksson L, McMahon K, Moudgil V, et al. Risk factors for clozapine-induced myocarditis and cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145:442–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13398.

Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, Topliss DJ, McNeil JJ. A new monitoring protocol for clozapine-induced myocarditis based on an analysis of 75 cases and 94 controls. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:458–65. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2011.572852.

Patel RK, Moore AM, Piper S, Sweeney M, Whiskey E, Cole G, et al. Clozapine and cardiotoxicity—a guide for psychiatrists written by cardiologists. Psychiatry Res. 2019;282: 112491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112491.

Griffin JM, Woznica E, Gilotra NA, Nucifora FC. Clozapine-associated myocarditis: a protocol for monitoring upon clozapine initiation and recommendations for how to conduct a clozapine rechallenge. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;41:180–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000001358.

Every-Palmer S, Inns SJ, Grant E, Ellis PM. Effects of clozapine on the gut: cross-sectional study of delayed gastric emptying and small and large intestinal dysmotility. CNS Drugs. 2019;33:81–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-018-0587-4.

Shirazi A, Stubbs B, Gomez L, Moore S, Gaughran F, Flanagan RJ, et al. Prevalence and predictors of clozapine-associated constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17060863.

Cohen D, Bogers JPAM, van Dijk D, Bakker B, Schulte PFJ. Beyond white blood cell monitoring: screening in the initial phase of clozapine therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1307–12. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.11r06977.

Cohen D. Clozapine and gastrointestinal hypomotility. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:1083–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-017-0481-5.

Palmer SE, McLean RM, Ellis PM, Harrison-Woolrych M. Life-threatening clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: an analysis of 102 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:759–68. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n0509.

West S, Rowbotham D, Xiong G, Kenedi C. Clozapine induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: A potentially life threatening adverse event A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;46:32–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.02.004.

McMillan SC, Williams FA. Validity and reliability of the constipation assessment scale. Cancer Nurs. 1989;12:183–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002820-198906000-00012.

Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1257–61. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035.

Every-Palmer S, Inns SJ, Ellis PM. Constipation screening in people taking clozapine: a diagnostic accuracy study. Schizophr Res. 2020;220:179–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.032.

Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM. Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: A 22-year bi-national pharmacovigilance study of serious or fatal “slow gut” reactions, and comparison with international drug safety advice. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:699–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-017-0448-6.

Stoecker ZR, George WT, O’Brien JB, Jancik J, Colon E, Rasimas JJ. Clozapine usage increases the incidence of pneumonia compared with risperidone and the general population: a retrospective comparison of clozapine, risperidone, and the general population in a single hospital over 25 months. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32:155–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0000000000000162.

de Leon J, Sanz EJ, Norén GN, De Las CC. Pneumonia may be more frequent and have more fatal outcomes with clozapine than with other second-generation antipsychotics. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:120–1. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20707.

Chang C-K, Chen P-H, Pan C-H, Su S-S, Tsai S-Y, Chen C-C, et al. Antipsychotic medications and the progression of upper respiratory infection to pneumonia in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:327–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.013.

De Leon J, Sanz EJ, De Las CC. Data from the world health organization’s pharmacovigilance database supports the prominent role of pneumonia in mortality associated with clozapine adverse drug reactions. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbz093.

Maher S, Cunningham A, O’Callaghan N, Byrne F, Mc Donald C, McInerney S, et al. Clozapine-induced hypersalivation: an estimate of prevalence, severity and impact on quality of life. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6:178–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125316641019.

Ishikawa S, Kobayashi M, Hashimoto N, Mikami H, Tanimura A, Narumi K, et al. Association between n-desmethylclozapine and clozapine-induced sialorrhea: involvement of increased nocturnal salivary secretion via muscarinic receptors by N-desmethylclozapine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2020;375:376–84. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.120.000164.

Thomas-Stonell N, Greenberg J. Three treatment approaches and clinical factors in the reduction of drooling. Dysphagia. 1988;3:73–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02412423.

Spivak B, Adlersberg S, Rosen L, Gonen N, Mester R, Weizman A. Trihexyphenidyl treatment of clozapine-induced hypersalivation. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12:213–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-199707000-00005.

Chen S-Y, Ravindran G, Zhang Q, Kisely S, Siskind D. Treatment strategies for clozapine-induced sialorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2019;33:225–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-019-00612-8.

Mubaslat O, Lambert T. The effect of sublingual atropine sulfate on clozapine-induced hypersalivation: a multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 2020;237:2905–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-020-05627-4.

Schoretsanitis G, Kuzin M, Kane JM, Hiemke C, Paulzen M, Haen E. Elevated clozapine concentrations in clozapine-treated patients with hypersalivation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60:329–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-020-00944-5.

Steinlechner S, Klein C, Moser A, Lencer R, Hagenah J. Botulinum toxin B as an effective and safe treatment for neuroleptic-induced sialorrhea. Psychopharmacology. 2010;207:593–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-009-1689-y.

Jackson A, Seneviratne U. EEG changes in patients on antipsychotic therapy: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;95:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.02.005.

Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C, Di Raimondo G, Di Perri R. Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold. Drug Saf. 2002;25:91–110. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200225020-00004.

Varma S, Bishara D, Besag FMC, Taylor D. Clozapine-related EEG changes and seizures: dose and plasma-level relationships. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2011;1:47–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125311405566.

Williams AM, Park SH. Seizure associated with clozapine: incidence, etiology, and management. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:101–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-014-0222-y.

Rohde C, Nielsen J. Managing common adverse effects of clozapine [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2018. Available from: http://www.oxfordmedicine.com/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780198828761.001.0001/med-9780198828761-chapter-7. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780198828761.003.0007

Devinsky O, Pacia SV. Seizures during clozapine therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:153–6.

Hjorthøj C, Stürup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0.

Westman J, Eriksson SV, Gissler M, Hällgren J, Prieto ML, Bobo WV, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality in people with schizophrenia: a 24-year national register study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27:519–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000166.