Abstract

Background and Objective

Biosimilars represent an opportunity to realise savings against the costs of innovative medicines. Despite efforts made by stakeholders, there are numerous barriers to the uptake of biosimilars. To realise the promise of biosimilars reducing costs, barriers must be identified, understood, and overcome, and enablers magnified. The aim of this systematic review is to summarise the enablers and barriers affecting uptake of biosimilars through the application of a classification system to organise them into healthcare professional (HCP), patient, or systemic categories.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, eConlit, and Embase. Included were primary research studies published in English between Jan 2017 through June 2023 focused on enablers and barriers affecting uptake of biosimilars. Excluded studies comprised comparisons of biosimilar efficacy and safety versus the reference biologic. One reviewer extracted data that included classification of barriers or enablers, the sub-classification, and the identification of the degree of agency associated with the actor through their role and associations as a mediator within their network, through the application of Actor Network Theory. The data were validated by a second reviewer (PV).

Results

Of the 94 studies included, 59 were cross-sectional, 20 were qualitative research, 12 were cohort studies, and three were economic evaluations. Within the review, 51 of the studies included HCP populations and 35 included patients. Policies and guidelines were the most cited group of enablers, overall. Systemic enablers were addressed in 29 studies. For patients, the most frequently cited enabler was positive framing of a biosimilar, while for HCPs, cost benefit was the most frequently noted enabler. The most frequently discussed systemic barrier to biosimilar acceptance was lack of effective policies or guidelines, followed by lack of financial incentives, while the most significant barriers for HCPs and patients, respectively, were their lack of general knowledge about biosimilars and concerns about safety and efficacy. Systemic actors and HCPs most frequently acted with broad degree of agency as mediators, while patient most frequently acted with a narrow degree of agency as mediators within their networks.

Conclusions

Barriers and enablers affecting uptake of biosimilars are interconnected within networks, and can be divided into systemic, HCP, and patient categories. Understanding the agency of actors within networks may allow for more comprehensive and effective approaches. Systemic enablers in the form of policies appear to be the most effective overall levers in affecting uptake of biosimilars, with policy makers advised to give careful consideration to appropriately educating HCPs and positively framing biosimilars for patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Factors affecting uptake of biosimilar medicines can be classified as either enablers or barriers. |

Barriers and enablers can be further divided into systemic, healthcare provider (HCP), and patient categories. |

Only four of the studies positioned the HCP as a mediator with narrow degree of agency within their role or assemblage, or effectively a limited-decision maker within the network, while in all others the HCP functioned as a mediator with broad degree of agency in their assemblage. In contrast, the patient or carer is most often positioned as a mediator with a narrow degree of agency within their network(s). |

The factors or actors (both human and non-human) affecting uptake of biosimilars each have agency and are interconnected within their networks. Careful consideration should be given to the interconnected nature of these factors when applying changes to individual actors. |

1 Introduction

Until recently, small molecule generic medicines served the role of driving down costs in medicines budgets and relieving substantial cost pressure within healthcare systems [1], but now biologic medicines occupy most of the top spending positions in medicines budgets [2]. This has resulted in a necessary shift of focus by third party payers and governments towards anticipated cost savings represented by biosimilar medicines. Biosimilar medicines are lower cost versions of their very expensive and widely used biologic reference medicine precursors that become available in markets once patent periods run out for these reference biologic medicines [3]. Biosimilars are accepted to be clinically equivalent to their reference biologic medicines in terms of efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity [4]. Biosimilars represent a key area of opportunity to realise savings against the significant costs of innovative biologic medicines [5], allowing for expanded access to currently available medicines, and funding innovative medicines.

1.1 Pharmaceutical Market Outlook and the Importance of Biosimilars

Biosimilars occupy 1% of the total biologic market in the world [6]. Uptake or adoption of biosimilars has been most successful in Europe, with 80% of biosimilar uptake being attributed to Europe [6], however, despite efforts by government and industry, uptake of biosimilars in Australia is lagging behind many other jurisdictions in the world [7], and therein lays the concern; with more expensive life-saving biologic medicines in development and entering the market, payers may be faced with absorbing the increasing costs of medicines, and particularly the costs of biologic medicines, unless they are able to realise savings through increased uptake of biosimilar medications.

Over the next 5–10 years, it is expected that the biosimilar market will peak in Europe, with an expected €8 billion value [8]. Over this period, it is expected that the most biologic losses of exclusivity (LOEs) will be in the oncology space (29%), followed by blood and lymphatic conditions (21%) [8]. It has been observed that drug development is now focused in the biologic and targeted medicines space. With this shift, drug budgets are escalating at rates not seen in the past, in many cases to unsustainable levels [9]. The future sustainability of medicines budgets and overall healthcare budgets may become more dependent upon the successful uptake of biosimilar medicines and the consequential cost savings [10]. Medicine markets around the world may need to consider making moves to drive up acceptance and adoption of biosimilar medicines, such that the biosimilar development pipeline remains viable, and to realise the cost savings offered by biosimilar medicines [10]. This will allow markets and payers to budget for and realise the advantages of newly developed medicines through reinvestment of these savings. Despite many of the efforts made by manufacturers, governments, payers, and representative organisations, uptake of biosimilars face numerous barriers [11]. To realise the opportunity of biosimilars reducing costs for healthcare systems and payers, barriers must be identified, understood, and overcome and enablers magnified.

Literature exists detailing the enablers and barriers affecting biosimilar uptake, mostly focused on specific factors such as healthcare professional (HCP) knowledge of and confidence in biosimilars, patient knowledge and confidence in biosimilars, and policies that limit uptake [12]. While this may be useful on a micro level or in overcoming specific jurisdictional concerns, there is a gap in the literature providing comprehensive views or applying useful models for understanding the enablers and barriers affecting the uptake of biosimilar medicines.

Additionally, there is inconsistency in how we classify these barriers and enablers [11, 12]. Importantly, there is a need to discuss how these barriers might be overcome, and/or enablers be magnified through identifying the interactions between actors within healthcare networks. Finally, there is a lack of discussion around the interconnectedness of actors within healthcare networks, affecting the uptake of biosimilar medicines.

The aim of this systematic review is to explore and summarise the enablers and barriers affecting uptake or use of biosimilar medicines through the application of a basic classification system, organising barriers and enablers into HCP, patient, or systemic categories, allowing for a clearer understanding, and how to potentially capitalise on or overcome them, respectively. Further to this, the actors affecting uptake of biosimilar medicines within their respective healthcare networks will be examined through the lens of the Actor Network Theory (ANT), allowing for a deeper understanding of the interdependencies between actors, and their roles and effects on each other.

Foundational to ANT is the concept of generalised symmetry, or the understanding that all actors, both human and non-human, within a network are afforded agency [13]. This principle contributes to the success of ANT through its extensibility and versatility [13]. Importantly, ANT removes any level of allocated power, rather allocating agency to each of the actors with nothing in between; “no aether in which networks should be immersed” [14]. The aim of ANT is not to “add social networks to social theory, but to rebuild social theory out of networks” [15]. This clear allocation of agency and removal of any additional social dynamic allows for a clearer view of the role of actors and how they interact with one another in a network to determine an outcome. This interconnected dynamic web of actors may act or be influenced by several other factors or actors within the network, functioning as mediators, transforming, translating, distorting, and modifying meaning, whose potential outcomes are effectively infinite or they may simply act as channels through which information in the network is passed in a binary way, functioning as intermediaries [15].

While not a foundational aspect of ANT, for our purposes, agency can be conceived as existing on a continuum, projecting from multiple sites within networks [16]. Our discussion will seek to expand on this theory and the shifts in agency resultant of the connections between or displacements created by actors.

2 Methods

The management and reporting of this review is in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRIMSA) [17].

2.1 Types of Studies

We included primary research studies, inclusive of all methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods) focused on enablers and barriers affecting the uptake of biosimilar medicines after regulatory approval and payer listing. Only studies written in English were included in this review. We excluded studies that focused on comparisons of biosimilar efficacy and safety versus the reference biologic, pharmacovigilance, biosimilar overviews, review articles, book chapters, books, book series, opinion articles, letters to the editor, and conference proceedings (Table 1).

2.2 Sources of Data

A determined, comprehensive search strategy was applied to PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, eConlit, and Embase from 2017 through June 2023. This period was selected based on the relative scarcity of primary research articles available in this space prior to 2017 in addition to the rapid advancements occurring in this space over the past 7 years.

2.3 Search Strategy

The specific search terms applied are provided in the electronic supplementary material (ESM) [18].

2.4 Review Methods

Three review authors (CR; GM; PV) independently screened all the titles and abstracts retrieved from the initial search and excluded irrelevant studies. We retrieved full-text articles for all eligible studies, and the two reviewers (CR; PV) independently selected studies for inclusion based on the inclusion criteria. The primary reviewer (CR) extracted data from the included studies utilising the standardised data extraction table (Excel) and the second reviewer (PV) validated the extracted data. The two reviewers (CR; PV) resolved any disagreements by consulting with the third reviewer (LH).

2.4.1 Analysis Framework and Theory

The following classification framework was applied throughout this systematic review: barriers and enablers classified as systemic, HCP, or patient. This model has been modified based on the proposed grouping of barriers developed by Cross et al. [12]. Further to this, both enablers and barriers were sub-classified to uncover trends.

Enablers or barriers were classified as systemic where said enablers or barriers were developed and/or implemented by a system administrator, such as, but not limited to, a hospital administrator or insurance provider. The outcomes in studies involving systemic actors often focused on enablers and barriers based on the workings of healthcare systems in areas of policy, governance, guidelines, coordination, and capacity. Within these systemic enablers and barriers categories, sub-categories were created. These categories were discussed and agreed upon by all reviewers. The following sub-categories within systematic enablers and barriers were agreed upon: (1) leadership and governance, (2) policies and guidelines, (3) product demand or availability, (4) service distribution and delivery, (5) costs of products, (6) financial capacity, (7) human resources capacity, (8) infrastructure and equipment capacity, (9) communication and education capacity, (10) health system levels coordination and integration, (11) intersectoral coordination and integration, and (12) others.

Studies involving HCP barriers and/or enablers had study populations consisting of or including HCPs, such as specialist clinicians, general practitioners, pharmacists, or nurses. The outcomes of these studies were focused on actions or reactions of HCPs. Studies involving patient barriers and/or enablers had study populations consisting exclusively of or including patients using or potentially eligible to use biologic or biosimilar medicines. Sub-categories of HCP and patient enablers and barriers were identified thematically through the extraction process. These sub-categories will be explored in further detail within the results section of this review.

The actors (human and non-human) involved in each of the included studies were analysed through the lens of Actor Network Theory (ANT). ANT, the foundational theory applied to this review, is a theoretical and methodological approach to social theory where everything in the social and natural worlds exists in constantly shifting networks of relationships [19]. Within this systematic review, each of the actors are viewed through their agency within their healthcare networks, whether they act as mediators with broad (effect on agency is broadened), narrow (agency is narrowed), or mixed (mixed or varying effect on agency) degrees of agency, resultant of their associations with other actors within their networks. This designation is an important representation of the role played by each individual actor. ANT affords ‘agency’, or the ability to do things, with an emphasis on either specific sites of action or aspects of social interaction (but not to be confused with human intentionality) [20]. Importantly, agency is attributed heterogeneously [21] to each of the actors that exist within a network, including both the human and non-human actors [19]. As an example, the clinician and the policy are both afforded agency in a network determining if a patient will use a biosimilar medicine.

Understanding the interconnectedness of the barriers and enablers affecting the uptake of biosimilar medicines is an important concept which can be further developed when viewed through the lens of ANT, which positions actors distributed heterogeneously across their networks [19]. Mediators possess the ability within their network(s) to determine a multitude of outcomes and possess agency [20], which for our purposes exists on a spectrum within the network and may be considered as broad, narrow, or mixed, while intermediaries effectively act as gates through which decisions or outcomes pass without being affected [20].

2.5 Data Extraction

Data was extracted according to the aforementioned classification framework on barriers and enablers affecting uptake of biosimilar medicines, their sub-classifications, and positioning of said barriers and enablers and/or the positioning of the actors within ANT. The following key data were extracted: (a) classification of barriers or enablers (systemic, HCP, or patient), (b) the sub-classification of the barriers or enablers described within each study, (c) the identification of the actor enabler or barrier as a mediator with broad, narrow, or mixed degree of agency within the context of the ANT, as a result of their associations or connections with the other actors within their assemblages or the entire network.

The following data were extracted using a purpose-built Excel spreadsheet: title, year, and country of publication, authors, Covidence unique identification code (code designated to each study by Covidence for data extraction purposes), objectives of the study, methods used in the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria applied, study instrument used, and the type of study (see ESM [18]).

2.6 Quality Appraisal

The primary reviewer (CR) assessed the methodological quality of each included study to determine the quality through the prospect of bias in its design, conduct, and analysis. The second reviewer (PV) validated the quality assessment completed by CR. The third reviewer (LH) resolved any disagreements through discussion with the two reviewers.

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools were utilised as the quality assessment tools for each of the included study types within this systematic review. JBI provides a set of critical appraisal tools for evaluating quantitative and qualitative study types. For this systematic review, the following JBI critical appraisal tools were applied: (1) analytical cross-sectional studies, (2) cohort studies, (3) economic evaluations, and (4) qualitative research study (see ESM [18]).

Each of the JBI tools provide specific criteria for evaluating selected study types. These criteria are included as Appendices to this systematic review (see ESM). The criteria that exist within each of the appraisal tools require Yes or No responses. The JBI Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies appraisal tool includes eight individual items for evaluation, the JBI Cohort Studies appraisal tool includes 11 individual items, the JBI Economic Evaluation appraisal tool has 11 items, and the JBI Qualitative Research appraisal tool includes ten items. The responses were tallied, leading to a raw score for each study. The totals for each study type have then been rolled up and averaged, with an average also being provided for all included studies within the systematic review, as a percentage. In scoring the included studies, one point was assigned for Yes, with zero points being assigned for No responses. The following classification system was employed for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies: a score of ≥ 6/8 indicates ‘High’, 3/6–5/6 ‘Medium’, and < 3/6 indicates ‘Poor’ quality. The following classification system was employed for both Cohort Studies and Economic Evaluations: ≥ 8/11 ‘High’, 5/11–7/11 ‘Medium’, and < 5/11 as ‘Poor’ quality. The following classification system was applied to Qualitative Research studies included in this systematic review: ≥ 7/10 ‘High’, 4/10–6/10 ‘Medium’, and < 4/10 ‘Poor’. No studies were excluded based on quality.

3 Results

3.1 Identification of Studies

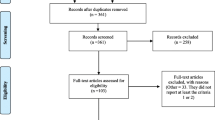

The search of the five databases resulted in identification of 11,541 studies, of which 1867 were duplicates. This resulted in 9674 studies remaining. A further 9399 studies were removed based on the author’s judgement of relevance of the title and abstract, and with 31 of the 275 remaining studies not available for retrieval, 244 articles were retrieved for full review. During the full review, 150 studies were excluded for the following reasons: (a) duplicates: 2 studies, (b) wrong study outcomes: 15 studies, (c) wrong study design: 95 studies, (d) non-primary research: 17 studies, (e) insufficient detail: 3 studies, (f) not available in English: 1 study, (g) outdated study: 17 studies (publication prior to 2016). This resulted in 94 studies being included in the final review. A PRISMA flowchart [22] is displayed in Fig. 1 outlining the inclusion and exclusion process for studies reviewed as part of this systematic review.

3.2 Characteristics of Included Studies

The characteristics of the 94 studies included in this systematic review are displayed in Supplementary Table 1 (see ESM). The included studies ranged in year of publication from 2017 to June 2023. There were 12 studies included from 2017 to 2018, while there were 58 studies included from 2019 to 2021. Of the 94 studies included, 59 were cross-sectional studies, 20 were qualitative research studies, 12 were cohort studies, and three were economic evaluations. There was an even split of six retrospective studies and six prospective studies within this category, with seven of these studies involving patients, two considering the actions or decisions of health professionals, while three examined decisions or actions by decision makers or others (payers, insurance providers) (Supplementary Table 1). These were either mixed methods or quantitative studies, with each of them looking at either experts, decision makers, or patient characteristics (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM).

Of the 59 cross-sectional studies, 55 used surveys as their primary research instrument, while three of these studies employed interviews, and two used statistical analysis of data. Of the 20 qualitative research studies, 16 of these studies using interviews as their primary study instrument. The remaining four used focus groups. Of the 12 cohort studies, six were prospective in nature, while the other six were retrospective. The economic evaluations were each designed to measure specific economic outcomes focused on biosimilar uptake and/or generated savings.

Of the 94 studies included, 42 were published in Europe, with 32 in North America, ten in Asia, four in Australia/New Zealand, and two for each of South America, Africa, and the Middle East. The country delivering the most publications was the United States of America (USA), with 31 of the included studies. The second largest contributor of studies was Belgium with ten (see Supplementary Table 2 in the ESM).

Within the systematic review, as detailed in Supplementary Table 1, 13 of the included studies were qualitative research, with 11 of these studies using interviews as their primary study instrument. The remaining two used focus groups. Most of the qualitative research involved multiple stakeholders (patients, health professionals, carers, experts, decision makers, or others), with seven of these studies involving experts or decision makers, while eight involved health professionals, six involved patients, two involved others (payers etc), and one involved carers.

3.3 Quality Appraisal

Applying the JBI framework, 89 of the 94 studies were rated as high according to the accepted scoring criteria. All 59 cross-sectional studies were rated as high with a scoring range of 6/8 to 8/8, while 18 of 19 qualitative research studies were rated as high, with one study rating as medium. The scoring range for qualitative research studies was 5/10 to 10/10, while nine of the 12 cohort studies rated as high, with the remaining three rating as medium. The scoring range for cohort studies was 5/11 to 11/11. All three of the included economic evaluations rated as high, with a scoring range of 8/11 to 11/11.

Most studies set out clear criteria for inclusion and exposure was measured in a valid way. However, where confounding factors were identified, there were often poor, or no strategies stated to deal with these (57 of 60 cross-sectional studies). Additionally, four of the 12 cohort studies did not clearly identify strategies for dealing with confounding factors (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM).

Notably, 13 of the 19 qualitative research studies did not clearly identify the researcher culturally or theoretically within the context of the research. Additionally, two of the three economic evaluations included did not adjust costs and outcomes for differential timing (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM).

3.4 Summary of Findings

The findings of the 94 studies included in this systematic review are included in Supplementary Table 1 (see ESM). This table includes details of the seven aspects considered in this review, including (1) year of publication, (2) country of publication, (3) approach (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods), (4) primary study instrument, (5) target population, (6) type of study, and (7) raw quality assessment score.

3.4.1 Target Populations of Included Studies

This systematic review found that most (46) studies (48.9%) included were focused on HCP-centric barriers or enablers, with systemic and patient-centric barriers and enablers holding a relatively equal share of the remainder at 28 studies (29.7%) and 33 studies (35.1%), respectively (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM). Within this systematic review, 51 of the studies included HCPs as targets of their studies, and the second most frequent study population being patients at 35 studies including patient populations (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM).

Of the 51 studies specifically examining HCP populations, 38 were cross-sectional studies and 11 were qualitative research. Of the 51 studies that examined HCPs as a target population, the literature points to specialist clinicians being the primary focus of research on enablers and barriers affecting biosimilars on health professionals, with 47 of these 51 studies focused on specialists, while 13 studies included pharmacists, and six included nurses (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM).

As outlined in Supplementary Table 1, the second most frequently studied population was patients and/or their carers, with 35 of the 94 studies including patients and/or carers within their study populations. The primary instruments applied to studying these patient or carer populations were surveys, with 17 of the 35 studies utilising surveys and another 12 studies applying interviews (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM). The primary aims of studies of patients were to examine their perceptions/attitudes and/or knowledge and/or understanding of biosimilar medicines, with 13 of the included studies examining these areas, and another ten studies examining patient perspectives about non-medical or mandated switches to biosimilar medications (see ESM [18]).

Importantly, the least frequently examined general population was decision makers, with 15 of the studies including decision makers within their target populations (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM). Decision makers can be broadly classified in this context as administrators and officials within healthcare institutions, government officials, or policy makers. The most applied instrument studying decision makers was interviews, with eight of the 15 studies utilising this method. Other instruments included surveys, cohort studies, literature reviews, cross-sectional studies, and economic analyses. Generally, the focus of these studies was to understand what has transpired to affect biosimilar uptake, and to understand what may be limiting, or what may drive increased uptake of biosimilars.

3.4.2 Barrier and Enabler Classification Framework

In reviewing the literature, three categories of barriers and enablers have emerged: barriers or enablers of patient acceptance or uptake, barriers or enablers of HCP acceptance and usage, and systemic enablers or barriers, including pricing, education, regulation, quotas, amongst others [12]. This categorisation of enablers and barriers assists in simplifying the view of the effect on uptake of biosimilars. Importantly, in orienting us to these classifications, systemic barriers and enablers can be viewed as foundational to both HCP and patient barriers and enablers. We will further explore the relationships between these classifications later in this review. Both enablers and barriers will be examined in detail, considering the most significant factors affecting uptake of biosimilar medications in each of the patient, HCP, and systemic categories. This examination will start with a consideration of enablers.

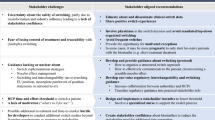

Table 2 provides a visual representation of the barrier and enabler classifications, with the vertical columns displaying the three classifications (systemic, HCP, and patient) and each of barriers and enablers. The horizontal rows represent the specific barriers or enablers detailed or discussed in the included articles and the frequency of occurrence (number of articles). Table 3 provides a visual representation of the roles played by the actors (HCPs, patients, systemic actors) through the lens of ANT, specifically mediators, with broad, narrow, or mixed degree of agency.

3.4.3 Enablers Facilitating Uptake of Biosimilar Medicines

Within this review, 29 of the 94 articles addressed or included systemic enablers. Of these 29 articles addressing systemic enablers, the most frequently cited type of enabler was policies and guidelines (25 articles). Further to this, policies and guidelines are the most cited group of enablers. However, as indicated earlier in this review, only 15 of the articles focused specifically on decision makers as a target population, instead looking at these systemic enablers through the lens of either the health care provider and/or the patient. In reviewing specific types of policies addressed, eight of the studies specifically considered mandatory or non-medical switching, while six of the studies considered incentives or gainshare arrangements (Table 2).

Financial capacity and cost savings were the other significant enablers in both the systemic and HCP categories, but interestingly, not the patient category. Financial capacity and cost savings were considered as systemic enablers in 14 studies, and HCP enablers in 12 studies (Table 2). Moorkens et al. [23] indicated that qualitative results of their study demonstrate that the price difference between biosimilar and originator products is an important factor in making it worthwhile to switch the patient. Further to this, Moorkens et al. [24] indicated in their 2019 study that relative difference in discounted price between the biosimilar and the originator product is a key driver of biosimilar medicines. The savings generated by utilising the lower cost biosimilar can be distributed through gain share agreements with key stakeholders.

In the patient category, the most frequently discussed enabler is utilisation of a medical interview, or positive framing of the switch to or start of a biosimilar medication, mentioned or discussed in six of the 24 studies involving patient populations (Table 2). Pouillon et al. [25] stated that the patient–health care provider relationship is a key driver of acceptance of biosimilars and limits risk of negative bias, going on to say that education about biosimilars should be tailored to the individual patient, taking into account nocebo effect risk profile. Further to this effect, Gasteiger et al. [26] indicated that positive framing by a clinician increased willingness to switch from 46 to 67%, while positive framing also increased perception of effectiveness of the biosimilar.

It has been observed through review of the literature that there are strong linkages or dependencies between the enablers. For instance, while a substitution policy may drive uptake of biosimilars, patient outcomes are somewhat dependent on patient–health care provider relationships [27]. Importantly, the confidence of the clinician or pharmacist in sharing information with the patient is dependent on their education and confidence in the efficacy and safety of the biosimilar medicines [28].

3.4.4 Barriers Inhibiting Uptake of Biosimilar Medicines

The perceived efficacy of biosimilar medicines is the most frequently discussed barrier to biosimilar acceptance by both HCPs and patients in the literature, with 22 articles discussing concerns about safety, efficacy, or limited knowledge of biosimilars by HCPs, and ten articles discussing efficacy or safety concerns by patients (Table 2). Edgar et al. [29] indicated in a 2021 study that one of the three hurdles to biosimilar adoption was the lack of confidence in biosimilar interchangeability and a need for education about biosimilars. From the patient perspective, a study by Teeple et al. [30] found that 85% of patients were concerned that biosimilars would not treat their disease as well.

Interestingly, a clear distinction has been observed in the literature between starting new patients on biosimilars and switching currently treated patients to a biosimilar. To highlight this, four articles indicated a higher comfort level in clinicians starting treatment-naïve patients on biosimilars, relative to switching. In a 2022 study, Demirkan et al. [31] found that nearly half (45%) of the paediatric rheumatologists surveyed preferred to prescribe biosimilars in the treatment of biologic-naïve cases.

In examining the systemic barriers to biosimilar use or acceptance, the most frequently discussed issue was lack of effective policies or guidelines (11 studies), followed by lack of financial or cost-saving incentives (six studies) (Table 2). Druedahl et al. [32], in a 2022 study of expert views, found that almost all participants saw no need for additional scientific data to support substitution, and urged greater policy debate on biosimilar substitution, urging European and UK policy makers and regulators to clarify their visions for biosimilar substitution. To expand on this, there is a distinction in the literature between demand- and supply-side policies. A study by Kim et al. [33] found that demand-side policies used in the UK and France have been more effective than the supply-side price linking policy used alongside few demand-side policies, where the volume of the originator brand of infliximab actually increased. A study by Barcina Lacosta et al. [34] lists the existence of policy frameworks that do not necessarily support the initiation of switching protocols as one of four key barriers to biosimilar uptake.

Several studies included in this review also mentioned the issue of the originator being advantaged through rebates or arrangements with insurance providers, limiting the use of biosimilars (Table 2). For instance, Herndon et al. [35] found, in a 2021 study, that rebate increases of reference biologics were rated as the highest (85%) barrier to health system adoption of biosimilars. While there are several types of barriers to the use of biosimilars, the literature has clearly identified that the most significant barriers are HCP and patient concerns about safety and efficacy, and their lack of general knowledge about biosimilars. From a systemic perspective, the most significant barriers are the lack of effective policies and guidelines, such that there are concerns about whether the promised cost savings of biosimilars can be achieved (Table 2).

3.4.5 Classification of Network Actors Within the Included Studies

Notably, only four of the studies (seven total scenarios) positioned the HCP as exclusively a mediator with a narrow degree of agency, or effectively a limited-decision maker within the network, while in all others the HCP functioned as a mediator with broad degree of agency (Table 3).

Interestingly, in each of these studies, the positioning of the HCP as a mediator with narrow degree of agency was the result of an insurance payer or institutional decision requiring patients to use biosimilar medications, effectively displacing the decision-making role from the clinician or pharmacist assemblage with the patient and shifting the balance of agency across the spectrum to the policy actor. An example of this was in Sullivan et al. [36], where patients were required to switch to biosimilar medications but were reluctant to accept biosimilar medications, highlighting the importance of patient and physician communication.

In contrast to the positioning of the HCP as a mediator with broad degree of agency, the patient or carer actor is most often positioned as a mediator with limited degree of agency in their assemblages with such actors as HCPs, insurance payers, and the medicines themselves within their network(s). In 13 of the included studies (22 total scenarios), the patient was positioned as an actor with narrow degree of agency, whereas the patient is positioned exclusively as a mediator with broad degree of agency in only eight of the studies (15 total scenarios) (Table 3).

4 Discussion

This systematic review summarises and explores the enablers and barriers affecting uptake or use of biosimilar medicines through the grouping of barriers and enablers into systemic, HCP, and patient categories. It differs from a previous systematic review of physicians’ perceptions of the uptake of biosimilars [6] and the assessment of a need for pharmacist-directed biosimilar education [37], by effectively scanning and categorising enablers and barriers. This is an important advancement in assessing how to improve uptake of biosimilar medicines through the magnification of enablers and overcoming of barriers. Additionally, this review considers the interconnectedness and roles played by the actors within networks affecting uptake of biosimilar medicines through the lens of ANT. The present systematic review is the first that we are aware of specifically considering all available worldwide English publications and classifying them in terms of types of enablers and barriers affecting uptake of biosimilar medicines.

Consideration of the target populations of the studies included in this systematic review is an important metric, as it provides us with insights around the focus of research in this space. This systematic review shows that the largest proportion of studies position the HCP (clinician, nurse, or pharmacist) as a mediator with broad degree of agency or having the ability to affect the prescribing outcome (determining if a biosimilar medication will be used) (Table 3). Further to this, findings demonstrate that clinicians are the most studied actors within networks affecting uptake of biosimilar medicines. However, findings show that policies and guidelines have the most significant effects in shifting the uptake of biosimilar medicines worldwide, but relatively few studies focus on key decision makers within healthcare networks who have the ability to create and enact policy changes.

Systemic actors, such as decision makers, guidelines, and policies, by their very nature are most often positioned as as mediators with broad degree of agency within their networks. When systemic actors, such as policies and guidelines, are positioned as mediators with broad degree of agency, there is a consequential alteration of roles played by other actors within the network(s), including HCPs and patients. Where HCPs may have previously held broader degrees of agency as mediators within the network, their agency is often narrowed when a systemic actor, such as a new policy enters the network. A clear example of this change occurs when a non-medical switching policy is adopted. Papautsky et al. [38] outlined experiences of clinicians and breast cancer patients non-medically switched to biosimilar trastuzumab when not initiated by the treating clinician, and found that there is a need for tailored and effective patient communication, and oncologist information and education on biosimilars, along with improved healthcare communication regarding switching, as clinicians in this study were unaware of the switch being initiated. Patients and clinicians in this study diverged on topics such as patient opportunity to ask questions, patients receiving adequate resources, and perception of the switch being minor in nature. The discrepancy between patient- and oncologist-reported experiences and perceptions highlights a lack of adequate information exchange between clinicians and patients. This demonstrates the importance of education and HCP engagement when specific types of policies are put in place with the intent of driving biosimilar use. While it is evident that each actor plays a role within the network(s), there is a critical interconnectedness which must be carefully considered and accounted for when making changes to their roles, such as in the case of non-medical switching.

Several of the studies referred to examples of non-medical switching, where patients were required to switch to biosimilar medicines by their payers (insurance payers). Chew et al. [39] outlined the concerns of patients when faced with a non-medical switch to a biosimilar, including cost concerns, drug properties, adverse events, drug packaging, and loss of disease control. A study by Petit et al. [27] indicated that tailored communication with a nurse reduced occurrence of the nocebo effect in non-medical switches. In this scenario, the patient functions as a mediator with narrow agency, but the patient still requires support to deliver the best possible medical outcomes. This highlights the interconnectedness or assemblages of actors and the importance of interactions between these actors as their roles or agency shift.

Touching on another important consideration, a 2022 study by Rupert et al. [28] found that HCP participants expressed reluctance to prescribe and dispense biosimilar and interchangeable products without seeing detailed efficacy and safety data; and physicians universally expressed disapproval that pharmacists could substitute interchangeable products for original products without prescriber consent. This study positions the prescriber as a mediator with broad degree of agency with the network, acting to evaluate safety and efficacy data, and making all prescribing and dispensing decisions. However, the interconnectedness of actors must be carefully weighed, considering impacts when their roles change.

Notably, within this review, patient populations were examined much less frequently in the included studies than HCPs (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM). This is an important observation, as patients are most often positioned within biologic/biosimilar actor networks as end points, whose understanding and acceptance of the medications is important. However, it is interesting to note that patients as actors most often played he role of mediator with less agency, with less agency, while HCPs more often played the role of mediator, taking on more agency as decision makers within their networks (Table 3). This dynamic could be an important consideration in determining how information is shared in situations such as non-medical switching.

The sharing of evidence-based information on the efficacy and safety of biosimilars, leading to increased knowledge of HCPs, was discussed as an enabler of biosimilar usage in 14 studies, where HCPs were included in the study populations. Peipert et al. [40], in a 2023 study of oncologists’ knowledge and perceptions of biosimilars, found that information on safety and efficacy was an important factor when considering the use of biosimilars. The confidence of clinicians and their ability to clearly communicate this with patients is evidently important in enabling patient acceptance. Building the confidence of the prescribing clinician or pharmacist is an important first step leading to successful patient interventions. This type of intervention could also lead to increased agency held patients, contributing to better outcomes. We can draw a reasonable deduction that the patients in these studies were less responsible for making their own decisions within their healthcare networks than HCPs in determining the use of biosimilar medicines.

These observations are important in generating an understanding of the roles played by the actors within healthcare networks, and how changes may be made to share agency more equitably around decision making or, in some cases, remove the decision-making roles of actors where this may result in a higher frequency of intended outcomes.

This systematic review has several strengths, including the application of a classification system for grouping enablers and barriers affecting biosimilar uptake. This study comprehensively reviewed available primary literature over a broad date range, ensuring adequate coverage of publications. This review also considered the roles played by human and non-human actors within healthcare networks and their interconnectedness in determining outcomes.

A key limitation of this study is the progressive nature of this space. Studies are being published at a rapid pace, leaving open the possibility of missed literature. Additionally, there is a level of subjectivity to rating articles through the quality assessment tool applied (JBI) and the cross-calculations between different study types. Finally, there is a level of subjectivity applied to extracting and classifying enablers, barriers, and the roles (mediators with broadened or narrowed degrees of agency) played by the actors within the articles, as these are not specifically identified within the articles. While every effort was made through primary and secondary reviews of the studies, and through quality checks of the extracted data, risk of error exists. It is suggested that further investigation be conducted around the interconnectedness of actors within these networks and the potential impacts of change in roles, particularly as new systemic actors, such as policies, are enacted.

5 Conclusions

Barriers and enablers affecting uptake of biosimilar medicines are interconnected within their networks, and can be divided into systemic, HCP, and patient categories. Understanding the agency of actors within networks may allow for more comprehensive and effective approaches. Systemic enablers and barriers, including policies, governance, and cost structures, by their nature function as mediators with broad degree of agency within their networks. The main barriers affecting acceptance of biosimilars for both HCPs and patients include general lack of knowledge of biosimilars, in addition to concerns about safety and efficacy. Enablers of uptake for HCPs often included structures creating cost savings. Systemic enablers in the form of policies appear to be the most effective overall levers in affecting uptake of biosimilars, with careful consideration given to appropriately educating HCPs and positively framing biosimilars for patients.

Decision makers contemplating altering policies which reposition the actors within networks, including HCPs and patients, are advised to be mindful of the importance of educational strategies, which may function to alleviate the concerns of HCPs around safety and efficacy of biosimilars, and that will equip them with the ability to more positively frame starts of and switches to biosimilar medicines, which is the most frequently named and successful enabler of biosimilar uptake for patients in this systematic review.

References

Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Societal value of generic medicines beyond cost-saving through reduced prices. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(4):701–11.

Modena V, Bianchi G, Roccatello D. Cost-effectiveness of biologic treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice: an achievable target? Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(8):835–8.

Government A. Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement - Outcomes: Biologics, F.A.a. Trade, Editor. 2016, Australian Government: Australia.

(EMA), E.M.A. Biosimilar medicines can be interchanged. 2022, European Medicines Agency.

Chaplin S. Biosimilars in the EU: a new guide for health professionals. Prescriber (London, England). 2017;28(10):27–31.

Sarnola K, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of the uptake of biosimilars: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5):e034183–e034183.

GaBi. Biosimilars in Australia—a-flagging and sustainability. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative 2021. https://www.gabionline.net/biosimilars/general/Biosimilars-in-Australia-a-flagging-and-sustainability. Accessed 19 Oct 2023

IQVIA. The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe. 2021 December 2021:[White Paper]. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe-2021.pdf. Accessed 5 Nov 2022.

Gronde TVD, Uyl-de Groot CA, Pieters T. Addressing the challenge of high-priced prescription drugs in the era of precision medicine: a systematic review of drug life cycles, therapeutic drug markets and regulatory frameworks. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182613.

Aitken M, et al. Advancing biosimilar sustainability in Europe-a multi-stakeholder assessment. London (UK): IQVIA; 2018.

Inotai A, et al. Patient access, unmet medical need, expected benefits, and concerns related to the utilisation of biosimilars in Eastern European Countries: a survey of experts. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9597362.

Cross RK, et al. Implementation strategies of biosimilars in healthcare systems: the path forward. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2022;15(2):45–52.

Blok A, Farias I, Roberts C. The Routledge companion to actor-network theory. London: Routledge; 2020. p. 22–53.

Latour B. On actor-network theory: a few clarifications. Soziale Welt. 1996;47(4):369–81.

Latour B. Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press Incorporated; 2005.

Bennett J. The agency of assemblages and the North American blackout. Public Cult. 2005;17(3):445–66.

Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339: b2700.

Rieger D, Hall VM, Biosimilar barriers and enablers systematic review—supporting dataset U.o. Queensland, Editor. Queensland, Australia; 2023. https://doi.org/10.48610/499274c.

Cressman D. A brief overview of actor-network theory: punctualization, heterogeneous engineering and translation. 2009.

Sayes E. Actor-network theory and methodology: just what does it mean to say that nonhumans have agency? Soc Stud Sci. 2014;44(1):134–49.

Dwiartama A, Rosin C. Exploring agency beyond humans: the compatibility of Actor-Network Theory (ANT) and resilience thinking. Ecol Soc. 2014;19(3).

Stovold E, et al. Study flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: an adapted PRISMA flow diagram. Syst Rev. 2014;3:1–5.

Moorkens E, et al. A look at the history of biosimilar adoption: characteristics of early and late adopters of infliximab and etanercept biosimilars in subregions of England, Scotland and Wales—a mixed methods study. BioDrugs. 2021;35(1):75–87.

Moorkens E, et al. Different policy measures and practices between swedish counties influence market dynamics: part 2—biosimilar and originator etanercept in the outpatient setting. BioDrugs. 2019;33(3):299–306.

Pouillon L, et al. Consensus report: clinical recommendations for the prevention and management of the nocebo effect in biosimilar-treated IBD patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(9):1181–7.

Gasteiger C, et al. Effects of message framing on patients’ perceptions and willingness to change to a biosimilar in a hypothetical drug switch. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72(9):1323–30.

Petit J, et al. Multidisciplinary team intervention to reduce the nocebo effect when switching from the originator infliximab to a biosimilar. RMD Open. 2021;7(1): e001396.

Rupert DJ, et al. Understanding US physician and pharmacist attitudes toward biosimilar products: a qualitative study. BioDrugs. 2022;36(5):645–55.

Edgar BS, et al. Overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption: real-world perspectives from a national payer and provider initiative. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(8):1129–35.

Teeple A, et al. Patient attitudes about non-medical switching to biosimilars: results from an online patient survey in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):603–9.

Demirkan FG, et al. Embracing change: an international survey study on the beliefs and attitudes of pediatric rheumatologists towards biosimilars. BioDrugs. 2022;36(3):421–30.

Druedahl LC, et al. Interchangeability of biosimilars: a study of expert views and visions regarding the science and substitution. PLoS One. 2022;17(1): e0262537.

Kim Y, et al. Uptake of biosimilar infliximab in the UK, France, Japan, and Korea: budget savings or market expansion across countries? Front Pharmacol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00970.

Barcina Lacosta T, et al. An exploration of biosimilar TNF-alpha inhibitors uptake determinants in hospital environments in Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Front Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1029040.

Herndon K, et al. Biosimilar perceptions among healthcare professionals and commercial medical benefit policy analysis in the United States. BioDrugs. 2021;35(1):103–12.

Sullivan E, et al. Assessing gastroenterologist and patient acceptance of biosimilars in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease across Germany. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175826–e0175826.

Mohd Sani N, et al. Pharmacists’ perspectives of biosimilars: a systematic review. BioDrugs. 2022;36(4):489–508.

Papautsky EL, et al. Characterizing experiences of non-medical switching to trastuzumab biosimilars using data from internet-based surveys with US-based oncologists and breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;194(1):25–33.

Chew C, et al. Patient perspectives on the British Columbia biosimilars initiative: a qualitative descriptive study. Rheumatol Int. 2021;42:1831–42.

Peipert JD, et al. Medical oncologists’ knowledge and perspectives on the use of biosimilars in the United States. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(3):e457–64.

Rémuzat C, et al. Key drivers for market penetration of biosimilars in Europe. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2017;5(1):1272308.

Waller J, et al. Assessing physician and patient acceptance of infliximab biosimilars in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis across Germany. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:519–30.

Chapman SR, Fitzpatrick RW, Aladul MI. Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare professionals towards infliximab and insulin glargine biosimilars: result of a UK web-based survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6): e016730.

O’Callaghan J, et al. Assessing awareness and attitudes of healthcare professionals on the use of biosimilar medicines: a survey of physicians and pharmacists in Ireland. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;88:252–61.

Beck M, et al. Knowledge, behaviors and practices of community and hospital pharmacists towards biosimilar medicines: results of a French web-based survey. MAbs. 2017;9(2):384–91.

Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Patients’ understanding and attitudes towards infliximab and etanercept biosimilars: result of a UK web-based survey. BioDrugs. 2017;31(5):439–46.

Monk BJ, et al. Barriers to the access of bevacizumab in patients with solid tumors and the potential impact of biosimilars: a physician survey. Pharmaceuticals. 2017;10(1):19.

Kabir ER, Moreino SS, SharifSiam MK. An empirical analysis of the perceived challenges and benefits of introducing biosimilars in Bangladesh: a paradigm shift. Biomolecules. 2018;8(3):89.

Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions and perspectives on biosimilar medicines and the barriers and facilitators to their prescribing in UK: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e023603–e023603.

Azevedo A, et al. Biosimilar agents for psoriasis treatment: the perspective of Portuguese patients. Acta Med Port. 2018;31(9):496–500.

Frantzen L, et al. Patients’ information and perspectives on biosimilars in rheumatology: a French nation-wide survey. Jt Bone Spine. 2019;86(4):491–6.

Karateev D, Belokoneva N. Evaluation of physicians’ knowledge and attitudes towards biosimilars in Russia and issues associated with their prescribing. Biomolecules. 2019;9(2):57.

Petitdidier N, et al. Patients’ perspectives after switching from infliximab to biosimilar CT- P13 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 12-month prospective cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(12):1652–60.

Hadoussa S, et al. Perception of hematologists and oncologists about the biosimilars: a prospective Tunisian study based on a survey. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26(1):124–32.

Teeple A, et al. Physician attitudes about non-medical switching to biosimilars: results from an online physician survey in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):611–7.

Haghnejad V, et al. Impact of a medical interview on the decision to switch from originator infliximab to its biosimilar in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(3):281–8.

Park S-K, et al. Knowledge and viewpoints on biosimilar monoclonal antibodies among Asian physicians: comparison with European Physicians. KJG. 2019;74(6):333–40.

Moorkens E, et al. Different policy measures and practices between Swedish counties influence market dynamics: part 1—biosimilar and originator infliximab in the hospital setting. BioDrugs. 2019;33(3):285–97.

Jensen TB, et al. The Danish model for the quick and safe implementation of infliximab and etanercept biosimilars. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):35–40.

Cook JW, et al. Academic oncology clinicians’ understanding of biosimilars and information needed before prescribing. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835918818335.

Tolonen HM, et al. Medication safety risks to be managed in national implementation of automatic substitution of biological medicines: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10): e032892.

Pawłowska I, et al. Perspectives of hospital pharmacists towards biosimilar medicines: a survey of polish pharmacy practice in general hospitals. BioDrugs. 2019;33(2):183–91.

Chau J, et al. Patient perspectives on switching from infliximab to infliximab-dyyb in patients with rheumatologic diseases in the United States. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2019;1(1):52–7.

Williamson CMM, Sullivan LBSB, Crawford TPBS, Lyman JMD, Md Mph Fasco Frcp GH. Addressing oncologists’ gaps in the use of biosimilar products. Evid Based Oncol. 2019;25(6):188–91.

Renton WD, et al. Same but different? A thematic analysis on adalimumab biosimilar switching among patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2019;17(1):67.

Giuliani R, et al. Knowledge and use of biosimilars in oncology: a survey by the European Society for Medical Oncology. ESMO open. 2019;4(2): e000460.

Scherlinger M, et al. Acceptance rate and sociological factors involved in the switch from originator to biosimilar etanercept (SB4). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48(5):927–32.

Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Differences in UK healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude and practice towards infliximab and insulin glargine biosimilars. Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;27(2):214–7.

Chan A, et al. Implementing and delivering a successful biosimilar switch programme—the Berkshire West experience. Future Healthc J. 2019;6(2):143–5.

Kovitwanichkanont T, et al. Who is afraid of biosimilars? Openness to biosimilars in an Australian cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med J. 2020;50(3):374–7.

Barbier L, et al. European stakeholder learnings regarding biosimilars: part II—improving biosimilar use in clinical practice. BioDrugs. 2020;34(6):797–808.

Moorkens E, et al. Learnings from regional market dynamics of originator and biosimilar infliximab and etanercept in Germany. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13(10):324.

Barbier L, et al. European stakeholder learnings regarding biosimilars: part I—improving biosimilar understanding and adoption. BioDrugs. 2020;34(6):783–96.

Baker JF, et al. Biosimilar uptake in academic and veterans health administration settings: influence of institutional incentives. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(7):1067–71.

Bhat S, et al. Process and clinical outcomes of a biosimilar adoption program with infliximab-Dyyb. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(4):410–6.

Chen AJ, Ribero R, Van Nuys K. Provider differences in biosimilar uptake in the filgrastim market. Methods. 2018.

Gibofsky A, McCabe D. US rheumatologists’ beliefs and knowledge about biosimilars: a survey. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(2):896–901.

Socal MP, et al. Biosimilar uptake in Medicare Part B varied across hospital outpatient departments and physician practices: the case of filgrastim. Value Health. 2020;23(4):481–6.

Chan A, et al. Assessing biosimilar education needs among oncology pharmacy practitioners worldwide: an ISOPP membership survey. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26(3_Suppl):11–21.

Saxby K, et al. A novel approach to support implementation of biosimilars within a UK tertiary hospital. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(1):23–8.

Socal MP, et al. Naming convention, interchangeability, and patient interest in biosimilars. Diabetes Spectrum. 2020;33(3):273–9.

Foreman E, et al. A survey of global biosimilar implementation practice conducted by the International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26(3_Suppl):22–32.

Gasteiger C, et al. Patients’ beliefs and behaviours are associated with perceptions of safety and concerns in a hypothetical biosimilar switch. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(1):163–71.

Mohammed AJ, Kadhim DJ. Knowledge and perception of Iraqi pharmacists towards biosimilar medicines. Iraqi J Pharm Sci. 2021;30(1):226–32 (P-ISSN 1683-3597 E-ISSN 2521-3512).

Kolbe AR, et al. Physician understanding and willingness to prescribe biosimilars: findings from a US National Survey. BioDrugs. 2021;35(3):363–72.

Vogler S, et al. Policies to encourage the use of biosimilars in european countries and their potential impact on pharmaceutical expenditure. Front Pharmacol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.625296.

Dean EB, Johnson P, Bond AM. Physician, practice, and patient characteristics associated with biosimilar use in medicare recipients. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034776–e2034776.

Vandenplas Y, et al. Off-patent biological and biosimilar medicines in Belgium: a market landscape analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.644187.

Barbier L, et al. Knowledge and perception of biosimilars in ambulatory care: a survey among Belgian community pharmacists and physicians. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):1–53.

Poon SY-K, et al. Assessing knowledge and attitude of healthcare professionals on biosimilars: a national survey for pharmacists and physicians in Taiwan. Healthcare. 2021;9(11):1600.

Druedahl LC, et al. Evolving biosimilar clinical requirements: a qualitative interview study with industry experts and European National Medicines Agency Regulators. BioDrugs. 2021;35(3):351–61.

Morris GA, et al. Increasing biosimilar utilization at a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease center and associated cost savings: show me the money. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;28(4):531–8.

Shakeel S, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards biosimilars and interchangeable products: a prescriptive insight by the pharmacists. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:1075–82.

Moorkens E, et al. The Expiry of Humira® market exclusivity and the entry of adalimumab biosimilars in Europe: an overview of pricing and national policy measures. Front Pharmacol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.591134.

Garcia KS, et al. Biosimilar knowledge and viewpoints among Brazilian inflammatory bowel disease patients. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211013248–17562848211013248.

Socal MP, et al. Biosimilar formulary placement in Medicare Part D prescription drug plans: a case study of infliximab. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;78(3):216–21.

Yang J, et al. Evolving perceptions, utilization, and real-world implementation experiences of oncology monoclonal antibody biosimilars in the USA: perspectives from both payers and physicians. BioDrugs. 2022;36(1):71–83.

Bernasko N, Clarke K. Why is there low utilization of biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease patients by gastroenterology advanced practice providers? Crohns Colitis 360. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/crocol/otab004.

Stevenson JG, et al. Pharmacist biosimilar survey reveals knowledge gaps. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2023;63(2):529–37 (e7).

Oqal M, et al. Awareness and knowledge of pharmacists toward biosimilar medicines: a survey in Jordan. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022:1–10.

Chong SC, et al. Perspectives toward biosimilars among oncologists: a Malaysian survey. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/10781552221104773.

Barbier L, et al. Biosimilar use and switching in Belgium: avenues for integrated policymaking. Front Pharmacol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.821616.

Resende HM, et al. Biosimilar use in breast cancer treatment: a national survey of Brazilian oncologists’ opinions, practices, and concerns. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:1316–24.

Vandenplas Y, et al. Perceptions about biosimilar medicines among Belgian patients in the ambulatory care. Front Pharmacol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.789640.

Hu Y, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare providers, healthcare regulatory practitioners and patients toward biosimilars in China: insights from a nationwide survey. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13: 876503.

Quinlivan A, et al. Attitudes of Australians with inflammatory arthritis to biologic therapy and biosimilars. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2022;6(3):rkac099.

Yossef L, et al. Patient and caregivers’ perspectives on biosimilar use in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022;75(1):59–63.

Krstic M, et al. Current expertise, opinions, and attitude toward TNF-⍺ antagonist biosimilars among physicians: a self-administered online survey in Western Switzerland. Healthcare. 2022;10(11):2152.

Varma M, Almarsdóttir AB, Druedahl LC. “Biosimilar, so it looks alike, but what does it mean?” A qualitative study of Danish patients’ perceptions of biosimilars. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2022;130(5):581–91.

Mohd Sani N, Aziz Z, Kamarulzaman A. Malaysian hospital pharmacists’ perspectives and their role in promoting biosimilar prescribing: a nationwide survey. BioDrugs. 2023;37(1):109–20.

Maltz RM, et al. Biosimilars for pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: pediatric gastroenterology clinical practice survey. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023;76(5):616–21.

Yu T, et al. Factors associated with biosimilar exclusions and step therapy restrictions among US commercial health plans. BioDrugs. 2023;37:1–10.

Chang J, et al. Provider barriers in uptake of biosimilars: case study on filgrastim. Am J Manag Care. 2023;29(5):e155–8.

Bourbeau B, et al. Biosimilar use among 38 ASCO PracticeNET practices, 2019–2021. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(7):516–22.

Funaki A, et al. Factors affecting patients’ acceptance of switching to biosimilars are disease-dependent: a cross-sectional study. Biol Pharm Bull. 2023;46(1):128–32.

Sharma A, et al. Biosimilars for retinal diseases: United States-Europe awareness survey (Bio-USER-survey). Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2023;23(8):851–9.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Not applicable. No funding was received in support of this publication.

Conflicts of interest

Author Chad Rieger is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia. He is also the Senior Medical Affairs Manager with Sandoz Pty Ltd, Australia & New Zealand. Appropriate disclosures on his work with Sandoz Pty Ltd have been made to ensure no interference with his academic work and specifically with this systematic review. No support or funding was provided for this work by Sandoz Pty Ltd, nor from any other party.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Patient consent to participate/publish

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Chad Rieger: Primary author, completion of search of databases and screening of titles and abstracts, full text review, data extraction, preparation of final manuscript, editing and final review of manuscript. Judith Dean: Secondary author, support of preparation of final manuscript, editing and final review of manuscript. Lisa Hall: Support of preparation of final manuscript, third reviewer on title and abstract screening, third reviewer on data extraction, editing and final review of manuscript. Paola Vasquez: Second reviewer on the title and abstract screening, full text review, and data extraction. Editing and final review of manuscript. Gregory Merlo: Second review on title and abstract screening, editing and final review of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rieger, C., Dean, J.A., Hall, L. et al. Barriers and Enablers Affecting the Uptake of Biosimilar Medicines Viewed Through the Lens of Actor Network Theory: A Systematic Review. BioDrugs 38, 541–555 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-024-00659-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-024-00659-0