Abstract

Objective

We explored the monetary value of the end-of-life (EoL) health gains, that is, the value of a life-year (VOLY) gained at the end of a patient’s life in Croatia. We tested whether the nature of the illness under valuation (cancer and/or rare disease) is a factor in the valuation of EoL-VOLYs. The aim was for our results to contribute to the health and longevity valuation literature and more particularly to the debate on the appropriate cost-effectiveness threshold for EoL treatments as well as to provide input into the debate on the justifiability of a cancer and/or a rare disease premium when evaluating therapies.

Methods

A contingent valuation was conducted in an online survey using a representative sample of the Croatian population (n = 1500) to calculate the willingness to pay for gains in the remaining life expectancy at the EoL, from the social-inclusive-individual perspective, using payment scales and an open-ended payment vehicle. Our approach mimics the actual decision-making problem of deciding whether to reimburse therapies targeting EoL conditions such as metastatic cancer whose main purpose is to extend life (and not add quality to life).

Results

Average EoL-VOLY across all scenarios was estimated at €67,000 (median €40,000). In scenarios that offered respondents 1 full year of life extension, EoL-VOLY was estimated at €33,000 (median €22,000). Our results show that the type of illness is irrelevant for EoL-VOLY evaluations.

Conclusions

The pressure to reimburse expensive therapies targeting EoL conditions will continue to increase. Delivering “value for money” in healthcare, both in countries with relatively higher and lower budget restrictions, requires the valuation of different types of health gains, which should, in turn, affect our ability to evaluate their cost effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

An alternative approach to calculating the VOLY would be, for instance, to value the reduction in the risk of dying in some future period or periods and to elicit the aggregate current WTP for marginal gains in individual life expectancy (and if those sum to 1 year, this would come close to the value of a statistical life [33]).

In terms of the design or the respondents’ comprehension of the tasks at hand.

Next to the questions presented here, the questionnaire also included a subset of unrelated questions.

Respondents who filled in the questionnaire in less than 10 minutes were considered to have clicked through the questionnaire and their responses were not delivered by the sampling agency.

Ensured by the professional sampling agency.

The same clear-cut conclusion could not be reached for QoL-related variation, possibly because respondents’ attention was more focused on LYG differences, owing to the properties of the design.

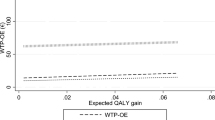

There is a positive and significant correlation between WTP-OE and LYG (r = 0.05, p = 0.01). In Table 4, we present the results of a linear regression with WTP-OE (not VOLY) as the dependent variable. In the linear regression, we test the theoretical validity of WTP-OE (raw estimates obtained from the survey). The results in Table 4 show that WTP-OE is sensitive to the length and the quality of life, when controlling for the other potential determinants (e.g., age, income). We tested whether other potentially important variables, such as the quadratic LYG and interaction between QoL and LYG should be included in the regression but this was dropped because of insignificance. The fact that the length of remaining life (variable LYG) has a positive coefficient, ceteris paribus, shows that across scenarios, a longer life expectancy (i.e., higher health gain) is associated with higher WTP-OE, as would be theoretically expected. However, when we recalculate WTP-OE into VOLYs by dividing raw WTP-OE values with the length of life in each row of data, the VOLY is on average lower for higher gains (i.e., longer life expectancy) than for smaller gains (i.e., shorter life expectancy). This is owing to the fact that raw WTP-OE values for a longer life expectancy (higher gains) are not proportionally higher than for a shorter life expectancy (lower gains), affecting the VOLY calculation’s results. Simply put, dividing relatively similar raw WTP-OEs across scenarios by very different life expectancy gains leads to higher VOLYs for smaller gains than for larger gains.

References

Brouwer W, van Baal P, van Exel J, Versteegh M. When is it too expensive? Cost-effectiveness thresholds and healthcare decision-making. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(2):175–80.

Claxton K, Walker S, Palmer S, Sculpher M. Appropriate perspectives for healthcare decisions. CHE Research Paper 54. York: Center for Health Economics, University of York; 2010.

Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health. 2016;19(8):929–35.

NICE. Appraising life-extending, end of life treatments. In: Research and Development, editor. Response to consultation. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2009.

NICE. Health technology evaluations: the manual. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/resources/nice-health-technology-evaluations-the-manual-pdf-72286779244741. Accessed 17 Sep 2023.

Dillon A, Landells LJ. NICE, the NHS, and cancer drugs. J Am Med Assoc. 2018;319:767–8.

Shah KK, Tsuchiya A, Wailoo AJ. Valuing health at the end of life: a review of stated preference studies in the social sciences literature. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:39–50.

Cohen D. Cancer drugs: high price, uncertain value. BMJ. 2017;359: j4543.

Cherny NI, Sullivan R, Dafni U, Kerst JM, Sobrero A, Zielinski C, et al. A standardised, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies: the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1547–73.

Davis C, Naci H, Gurpinar E, Poplavska E, Pinto A, Aggarwal A. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009–13. BMJ. 2017;359: j4530.

Viscusi WK, Huber J, Bell J. Assessing whether there is a cancer premium for the value of a statistical life. Health Econ. 2014;23(4):384–96.

Shah KK. Is willingness to pay higher for cancer prevention and treatment? J Cancer Policy. 2017;11:60–4.

Aggarwal A, Fojo T, Chamberlain C, Davis C, Sullivan R. Do patient access schemes for high-cost cancer drugs deliver value to society? Lessons from the NHS Cancer Drugs Fund. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1738–50.

McCabe C, Claxton K, Tsuchiya A. Orphan drugs and the NHS: should we value rarity? BMJ. 2005;331(7523):1016–9.

Obradovic M, Mrhar A, Kos M. Willingness to pay for a life-year gained from the perspective of the general population. Value Health. 2009;12:A284.

Markiewicz O. Value of life year and cost-effectiveness thresholds: the case of Poland. Central Eur Econ J. 2021;8(55):256–68. https://doi.org/10.2478/ceej-2021-0019.

Wilson R, Crouch EAC. Risk-benefit analysis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2001.

Hammitt JK. Valuing changes in mortality risk: lives saved vs. life years saved. Review of environmental economics and policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Brunekreef B, Miller BG, Hurley JF. The brave new world of lives sacrificed and saved, deaths attributed and avoided. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):785–8.

Desaigues B, Ami D, Bartczak A, Braun-Kohlová M, Chilton S, Czajkowski M, et al. Economic valuation of air pollution mortality: a 9-country contingent valuation survey of value of a life year (VOLY). Ecol Ind. 2011;11(3):902–10.

Ryen L, Svensson M. The willingness to pay for a quality adjusted life year: a review of the empirical literature. Health Econ. 2015;24(10):1289–301.

Nimdet K, Chaiyakunapruk N, Vichansavakul K, Ngorsuraches S. A systematic review of studies eliciting willingness-to-pay per quality-adjusted life year: does it justify CE threshold? PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4): e0122760.

Mac Ardy Junio G, Thavorncharoensap M, Chaikledkaew U, Youngkong S, Thakkinstian A, Culyer AJ. A systematic review of demand-side methods of estimating the societal monetary value of health gain. Value Health. 2021;24(10):1423–34.

Ahlert M, Breyer F, Schwettmann L. How you ask is what you get: framing effects in willingness-to-pay for a QALY. Soc Sci Med. 2016;150:40–8.

Igarashi A, Goto R, Yoneyama-Hirozane M. Willingness to pay for QALY: perspectives and contexts in Japan. J Med Econ. 2019;22(10):1041–6.

Pennington M, Baker R, Brouwer W, Mason H, Hansen DG, Robinson A, EuroVaQ Team, et al. Comparing WTP values of different types of QALY gain elicited from the general public. Health Econ. 2015;24(3):280–93.

Shiroiwa T, Igarashi A, Fukuda T, Ikeda S. WTP for a QALY and health states: more money for severer health states? Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11:1–7.

Finkelstein EA, Bilger M, Flynn TN, Malhotra C. Preferences for end-of-life care among community-dwelling older adults and patients with advanced cancer: a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy. 2015;119(11):1482–9.

Pinto-Prades JL, Sánchez-Martínez FI, Corbacho B, Baker R. Valuing QALYs at the end of life. Soc Sci Med. 2014;113:5–14.

Soini J, Kukkonen E, Myllykangas J, Ryynanen M.OP. Contingent valuation of eight new treatments: what is the clinician's and politician's willingness to pay? Open Complement Med J. 2012;4(1).

Dolan P, Olsen JA, Menzel P, Richardson J. An inquiry into the different perspective that can be used when elicting preferences in health. Health Econ. 2003;12:545–51.

Tsuchiya A, Watson V. Re-thinking the different perspectives that can be used when eliciting preferences in health. Health Econ. 2017;26(12):e103–7.

Jones-Lee M, Chilton S, Metcalf H, Nielsen JS. Valuing gains in life expectancy: clarifying some ambiguities. J Risk Uncertain. 2015;51(1):1–21.

Round J. Is a QALY still a QALY at the end of life? J Health Econ. 2012;31(3):521–7.

Vončina L, Strbad T, Fürst J, Dimitrova M, Kamusheva M, Vila M, et al. Pricing and reimbursement of patent-protected medicines: challenges and lessons from South-Eastern Europe. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19(11):915–27.

Kovács S, Németh B, Erdősi D, Brodszky V, Boncz I, Kaló Z, et al. Should Hungary pay more for a QALY gain than higher-income Western European countries? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2022;20(3):291–303.

Németh B, Csanádi M, Inotai A, Ameyaw D, Kaló Z. Access to high-priced medicines in lower-income countries in the WHO European region. Oslo Medicines Initiative technical report. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022.

Haninger K, Hammitt JK. Diminishing willingness to pay per quality-adjusted life year: valuing acute foodborne illness. Risk Anal. 2011;31(9):1363–80.

Bobinac A, van Exel NJA, Rutten FF, Brouwer WB. Get more, pay more? An elaborate test of construct validity of willingness to pay per QALY estimates obtained through contingent valuation. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):158–68.

Chilton S, Jones-Lee M, Metcalf H, Seested Nielsen J, Baker R, Donaldson C, et al. A scoping study on the valuation of risks to life and health: the monetary value of a life year (VOLY). Newcastle University, Glasgow Caledonian University, University of Birmingham. 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/903543/voly-scoping_study-report.pdf. Accessed 17 Sep 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The work of the authors is partly supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under project UIP-2019-04-3721.

Conflict of interest

Elizabeta Ribarić, Ismar Velić, and Ana Bobinac have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

See the Electronic Supplementary Material.

Consent to participate

Before starting the survey, each respondents agreed to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Before starting the survey, each respondent consented to the survey data being used for research, publication, and dissemination purposes.

Availability of data and material

The dataset is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used for the data analysis is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

Each author has made a substantial contribution to the concept and the design of the article; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data for the article, and has participated in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Finally, each author has approved the version to be published.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

An example of the wording:

Imagine a person who went to a medical examination during this week due to the appearance of certain health problems. After the examinations, the doctor informs her that she is suffering from a SERIOUS DISEASE (advanced form of cancer) and that with USUAL TREATMENT she can live another 6 months. Assume that this happens to 1,000 patients in Croatia annually (3 people per 10,000 inhabitants), among whom might be you. However, in addition to the usual treatment, there is also a new drug that can extend the life of affected people for an additional 4 years (4 and a half years in total), while keeping the quality of life at the same level, as shown in the graph below. After 4.5 years the patients will die.

Assume that the healthcare system does not have enough money to pay for this medicine, and that is why a new tax is being introduced in Croatia, which will be paid by all people over the age of 18 (regardless of whether they belong to the risk group), once a month for 12 months. The tax will be abolished after 12 months.

On the scale, mark the highest tax that you would certainly pay/certainly not pay for the new drug every month for the next year.

0 kn | 1 kn | 3 kn | 5 kn | 7 kn | 10 kn | 13 kn | 15 kn | 17 kn | 20 kn | 23 kn | 25 kn | 30 kn | 35 kn | 40 kn | 45 kn | 50 kn | 60 kn | 70 kn | 80 kn | 100 kn | 300 kn |

In the previous answers, you stated that you would certainly pay x kuna every month for the next year, while you would certainly not pay y kuna.

Indicate the exact amount of tax (in the range of x to y kuna) that you would surely pay every month for the next year, in order to prolong the life of the persons in the risk group, among whom you might be. When answering, take into account the total monthly income of your household!

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ribarić, E., Velić, I. & Bobinac, A. VOLY: The Monetary Value of a Life-Year at the End of Patients’ Lives. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 22, 97–106 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-023-00829-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-023-00829-1