Abstract

Background

As tuberculosis screening trends to targeting high-risk populations, knowing the cost effectiveness of such screening is vital to decision makers.

Objectives

The purpose of this review was to compile cost-utility analyses evaluating latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) screening in high-risk populations that used quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) as their measure of effectiveness.

Data Sources

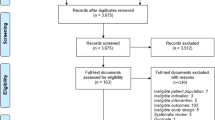

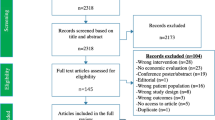

A literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Knowledge, and PubMed was performed from database start to November 2014.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies performed in populations at high risk of LTBI and subsequent reactivation that used the QALY as an effectiveness measure were included.

Study Appraisal and Synthesis

Quality was assessed using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist. Data extracted included tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) use, economic, screening, treatment, health state, and epidemiologic parameters. Data were summarized in regard to consistency in model parameters and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), with costs adjusted to 2013 US dollars.

Results

Of 415 studies identified, ultimately eight studies were included in the review. Most took a societal perspective (n = 4), used lifetime time horizons (n = 6), and used Markov models (n = 8). Screening of adult immigrants was found to be cost effective with a TST in one study, but moderately cost effective with an IGRA in another study; screening immigrants arriving more than 5 years prior with an IGRA was moderately cost effective until 44 years of age (n = 1). Screening HIV-positive patients was highly cost effective with a TST (n = 1) and moderately cost effective with an IGRA (n = 1). Screening in those with renal diseases (n = 2) and diabetes (n = 1) was not cost effective.

Limitations

Very few studies used the QALY as their effectiveness measure. Parameter and study design inconsistencies limit the comparability of studies.

Conclusions

With validity issues in terms of parameters and assumptions, any conclusion should be interpreted with caution. Despite this, some cautionary recommendations emerged: screening HIV patients with a TST is highly cost effective, while screening adult immigrants with an IGRA is moderately cost effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Global tuberculosis report 2012. Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Walter ND, Painter J, Parker M, Lowenthal P, Flood J, Fu Y, et al. Persistent latent tuberculosis reactivation risk in United States immigrants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:88–95.

Sudre P, ten Dam G, Kochi A. Tuberculosis: a global overview of the situation today. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70:149–59.

Canadian Tuberculosis Standards. 7th edn. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Thoracic Society. 2013. http://www.respiratoryguidelines.ca/tb-standards-2013. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Framework towards TB elimination in low-incidence countries. Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/132231/1/9789241507707_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Tuberculosis: clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. Manchester (UK): National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13422/53642/53642.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/diagnosis.htm. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Jerant A, Bannon M, Rittenhouse S. Identification and management of tuberculosis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(2667–78):2681–2.

Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:340–54.

Mazurek GH, Villarino ME, CDC. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB test for diagnosing latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:15–8.

Chee CBE, KhinMar KW, Gan SH, Barkham TMS, Pushparani M, Wang YT. Latent tuberculosis infection treatment and T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigens. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:282–7.

MacPherson P, Houben RM, Glynn JR, Corbett EL, Kranzer K. Pre-treatment loss to follow-up in tuberculosis patients in low- and lower-middle-income countries and high-burden countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:126–38.

Campbell J, Marra F, Cook V, Johnston J. Screening immigrants for latent tuberculosis: do we have the resources? CMAJ. 2014;186:246–7.

Lorgelly PK, Lawson KD, Fenwick EAL, Briggs AH. Outcome measurement in economic evaluations of public health interventions: a role for the capability approach? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:2274–89.

Robberstad B. QALYs vs DALYs vs LYs gained: what are the differences, and what difference do they make for health care priority setting? Nor Epidemiol. 2005;15(2):183–91.

Russell LB, Gold MR, Siegel JE, Daniels N, Weinstein MC. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:1172–7.

Weinstein MC, Torrance G, McGuire A. QALYs: the basics. Value Health. 2009;12:S5–9.

Garrison LP. Editorial: on the benefits of modeling using QALYs for societal resource allocation: the model is the message. Value Health. 2009;12:S36–7.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(264–9):W64.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) statement. BMC Med. 2013;11:80.

Consumer Price Indices (MEI). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2015. http://stats.oecd.org/. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Laupacis A, Feeny D, Detsky AS, Tugwell PX. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization? Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. CMAJ. 1992;146:473–81.

Robert M, Kaplan JWB. Health-related quality of life measurement for evaluation research and policy analysis. Health Psychol. 1982;1:61–80.

Kowada A. Cost effectiveness of interferon-γ release assay for TB screening of HIV positive pregnant women in low TB incidence countries. J Infect. 2014;68:32–42.

Kowada A. Cost effectiveness of interferon-gamma release assay for tuberculosis screening of rheumatoid arthritis patients prior to initiation of tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist therapy. Mol Diagn Ther. 2010;14:367–73.

Kowada A. Cost effectiveness of the interferon-γ release assay for tuberculosis screening of hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:682–8.

Laskin BL, Goebel J, Starke JR, Schauer DP, Eckman MH. Cost-effectiveness of latent tuberculosis screening before steroid therapy for idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:22–32.

Shrestha RK, Mugisha B, Bunnell R, Mermin J, Odeke R, Madra P, et al. Cost-utility of tuberculosis prevention among HIV-infected adults in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:747–54.

Linas BP, Wong AY, Freedberg KA, Horsburgh CR. Priorities for screening and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:590–601.

Burgos JL, Kahn JG, Strathdee SA, Valencia-Mendoza A, Bautista-Arredondo S, Laniado-Laborin R, et al. Targeted screening and treatment for latent tuberculosis infection using QuantiFERON-TB Gold is cost-effective in Mexico. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:962–8.

Khan K, Muennig P, Behta M, Zivin JG. Global Drug-resistance patterns and the management of latent tuberculosis infection in immigrants to the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1850–9.

Schackman BR, Goldie SJ, Freedberg KA, Losina E, Brazier J, Weinstein MC. Comparison of health state utilities using community and patient preference weights derived from a survey of patients with HIV/AIDS. Med Decis Making. 2002;22:27–38.

Li J, Munsiff SS, Tarantino T, Dorsinville M. Adherence to treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in a clinical population in New York City. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e292–7.

Horsburgh CR, O’Donnell M, Chamblee S, Moreland JL, Johnson J, Marsh BJ, et al. Revisiting rates of reactivation tuberculosis: a population-based approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:420–5.

Lee SSJ, Chou KJ, Su IJ, Chen YS, Fang HC, Huang TS, et al. High prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection in patients in end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis: comparison of QuantiFERON-TB GOLD, ELISPOT, and tuberculin skin test. Infection. 2009;37:96–102.

Shankar MSR, Aravindan AN, Sohal PM, Kohli HS, Sud K, Gupta KL, et al. The prevalence of tuberculin sensitivity and anergy in chronic renal failure in an endemic area: tuberculin test and the risk of post-transplant tuberculosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:2720–4.

Abdel-Nabi EA, Eissa SA, Soliman YMA, Amin WA. Quantiferon vs. tuberculin testing in detection of latent tuberculous infection among chronic renal failure patients. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2014;63:161–5.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance G, O’Brien B, Stoddart G. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes, vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. http://www.amazon.ca/Methods-Economic-Evaluation-Health-Programmes/dp/0198529457.

Shiroiwa T, Sung Y-K, Fukuda T, Lang H-C, Bae S-C, Tsutani K. International survey on willingness-to-pay (WTP) for one additional QALY gained: what is the threshold of cost effectiveness? Health Econ. 2010;19:422–37.

Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. London (UK): National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2013. http://publications.nice.org.uk/pmg9. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. Canada: WHO. 2001. http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/pe/PEAMMarch2005/CMHReport.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Shillcutt SD, Walker DG, Goodman CA, Mills AJ. Cost-effectiveness in low- and middle-income countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:903–17.

Azadi M, Bishai DM, Dowdy DW, Moulton LH, Cavalcante S, Saraceni V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis screening and isoniazid treatment in the TB/HIV in Rio (THRio) Study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:1443–8.

Buxton MJ, Lacey LA, Feagan BG, Niecko T, Miller DW, Townsend RJ. Mapping from disease-specific measures to utility: an analysis of the relationships between the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire and Crohn’s Disease Activity Index in Crohn’s disease and measures of utility. Value Health. 2007;10:214–20.

Sauerland S, Weiner S, Dolezalova K, Angrisani L, Noguera CM, García-Caballero M, et al. Mapping utility scores from a disease-specific quality-of-life measure in bariatric surgery patients. Value Health. 2009;12:364–70.

Grimison PS, Simes RJ, Hudson HM, Stockler MR. Deriving a patient-based utility index from a cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire. Value Health. 2009;12:800–7.

Taylor Z, Nolan CM, Blumberg HM. American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Recommendations from the American Thoracic Society, CDC, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54:1–81.

Tuberculosis (TB): CDNA National Guidelines for the Public Health Management of TB. Canberra (AU): Department of Health. 2013. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/D140EDF48C0A0CEACA257BF0001A3537/$File/TB-SoNG-July-2013.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Global Tuberculosis Report 2014. Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/137094/1/9789241564809_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Guidelines on the management of latent tuberculosis infection. Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/136471/1/9789241548908_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1. Accessed 28 May 2015.

Nienhaus A, Schablon A, Costa JT, Diel R. Systematic review of cost and cost-effectiveness of different TB-screening strategies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:247.

Redelman-Sidi G, Sepkowitz KA. IFN-γ release assays in the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection among immunocompromised adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:422–31.

Oxlade O, Pinto M, Trajman A, Menzies D. How methodologic differences affect results of economic analyses: a systematic review of interferon gamma release assays for the diagnosis of LTBI. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56044.

Marra CA, Woolcott JC, Kopec JA, Shojania K, Offer R, Brazier JE, et al. A comparison of generic, indirect utility measures (the HUI2, HUI3, SF-6D, and the EQ-5D) and disease-specific instruments (the RAQoL and the HAQ) in rheumatoid arthritis. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1571–82.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have received no funding for the purposes of this review. JRC, TS and FM have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

JRC: Helped determine study objective and guide discussion points. Performed the literature review, quality assessment, data extraction, and data analysis. Did drafting of the initial manuscript and drafting of revisions. Guarantor of the overall content.

TS: Replicated the literature review, quality assessment, and data extraction to ensure accuracy. FM: Helped determine study objective and guide discussion points. Provided expert opinion and was heavily involved in initial and revision drafting.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, J.R., Sasitharan, T. & Marra, F. A Systematic Review of Studies Evaluating the Cost Utility of Screening High-Risk Populations for Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 13, 325–340 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-015-0183-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-015-0183-4