Abstract

Objective

The Affordable Care Act is currently in the roll-out phase. To gauge the likely implications of the national policy we analyze how the Massachusetts Health Care Reform Act impacted various hospitalization outcomes in each of the 25 major diagnostic categories (MDC).

Methods

We utilize a difference-in-difference approach to identify the impact of the Massachusetts reform on insurance coverage and patient outcomes. This identification is achieved using six years of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. We report MDC-specific estimates of the impact of the reform on insurance coverage and type as well as length of stay, number of diagnoses, and number of procedures.

Results

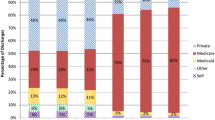

The requirement of universal insurance coverage increased the probability of being covered by insurance. This increase was in part a result of an increase in the probability of being covered by Medicaid. The percentage of admissions covered by private insurance fell. The number of diagnoses rose as a result of the law in the vast majority of diagnostic categories. Our results related to length of stay suggest that looking at aggregate results hides a wealth of information. The most disparate outcomes were pregnancy related. The length of stay for new-born babies and neonates rose dramatically. In aggregate, this increase serves to mute decreases across other diagnoses. Also, the number of procedures fell within the MDCs for pregnancy and child birth and that for new-born babies and neonates.

Conclusions

The Massachusetts Health Care Reform appears to have been effective at increasing insurance take-up rates. These increases may have come at the cost of lower private insurance coverage. The number of diagnoses per admission was increased by the policy across nearly all MDCs. Understanding the changes in length of stay as a result of the Massachusetts reform, and perhaps the Affordable Care Act, requires MDC-specific analysis. It appears that the most important distinction to make is to differentiate care related to new-born babies and neonates from that related to other diagnostic categories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this paper, emergency room (ER) visits that result in admission to the hospital are considered inpatient ER use and those that do not are considered outpatient ER use.

Kolstad and Kowalski [6] investigate on a sample ranging from 2004 to 2008; however, instead of just some northeastern states they include 41 states as a control group in their sample.

Income and hospital size dummy variables are used as defined in the NIS. Income is a quartile classification of median household income for the patients’ zip code. The income quartiles are updated annually. In 2006 the quartiles were less than $37,999, $38,000–$46,999, $47,000–$61,999, and greater than $62,000, respectively. Hospital size is based on an urban-teaching status matrix. For example, for an urban teaching hospital, small, medium, and large hospitals are defined as less than 249 beds, 250–424 beds, and more than 425 beds, respectively.

Please see the Electronic Supplementary Material for full details of summary statistics and model estimation.

References

Report to the Massachusetts Legislature: Implementation of the Health Care Reform Law, Chapter 58, 2006–2008. The Massachusetts Health Insurance Connector Authority 2008.

Report to the Massachusetts Legislature: Implementation of the Health Care Reform, Fiscal Year 2010. The Massachusetts Health Insurance Connector Authority 2010.

Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. The importance of the individual mandate—evidence from Massachusetts. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(4):293–5.

Long SK, Stockley K, Yemane A. Another look at the impacts of health reform in Massachusetts: evidence using new data and a stronger model. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc. 2009;99(2):508–11.

Yelowitz A, Cannon MF. The Massachusetts health plan: much pain, little gain. Policy Analysis Working Paper 657. 2010.

Kolstand JT, Kowalski AE. The impact of health care reform on hospital and preventive care: evidence from Massachusetts. J Public Econ. 2012;96(11–12):909–29.

Cozad M. Better to be safe than sorry? The supply side effects of Massachusetts health care reform on hospitals. Working Paper, Furman University. 2012.

Cozad M, Wichmann B. Efficiency of health care delivery systems: effects of health insurance coverage. Appl Econ. 2013;4(29):4082–94.

Chen C, Scheffler G, Chandra A. Massachusetts’ health care reform and emergency department utilization. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(e25):1–3.

Miller S. The effect of insurance on outpatient emergency room visits: an analysis of the 2006 Massachusetts health reform. J Public Econ. 2012;96(11–12):893–908.

HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Rockville, MD: Healthcare Cost and Utilitization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004–2008.

Bebinger M. Mission not yet accomplished? Massachusetts contemplates major moves on cost containment. Health Aff. 2009;28(3):1373–81.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Editor, Tim Wrightson and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. The authors alone are responsible for findings and views contained in this paper.

Financial support from the Rea and Lillian Steele Summer Grant and the Center for Faculty Scholarship, both at the Valdosta State University, for A. Cseh is gratefully acknowledged. B. Koford would like to acknowledge support from the Smith Research Fellowship, John B. Goddard School of Business and Economics, Weber State University.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions

A. Cseh designed and estimated the econometric models and is the lead author. A. Cseh, B. Koford, and R. Phelps contributed to the discussion and evaluation of the literature, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. The authors share responsibility for guaranteeing the content of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cseh, A., Koford, B.C. & Phelps, R.T. Hospital Utilization and Universal Health Insurance Coverage: Evidence from the Massachusetts Health Care Reform Act. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 13, 627–635 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-015-0178-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-015-0178-1